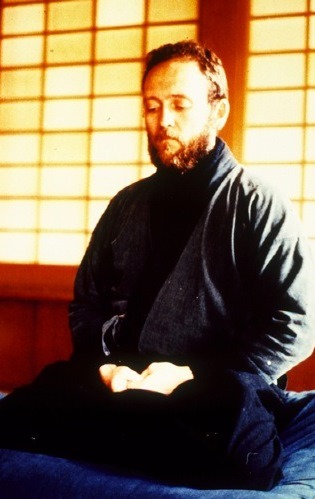

Deep Streams Zen, Los Angeles, California

“I first encountered something like Buddhism when I was a freshman at CCNY,” Joseph Bobrow tells me. “I took a psychopathology lecture class with this dynamic teacher who was very Freudian but very open-minded, so I decided to take another class from him, a survey course on contemporary psychotherapy treatment. And as one of the reading options there was a book called The First and Last Freedom by Krishnamurti, and I read it, and I just came alive.”

While still a child in the first decade of the 20th century, Jiddu Krishnamurti had been discovered by members of the Theosophical Society who believed him to be the reincarnation of the Buddha and trained him to be the next World Teacher. By the time he was 34, Krishnamurti denied these claims, although he did continue to teach, drawing crowds around the world. Among his various accomplishments, he co-founded the Happy Valley School in Ojai, California.

Like the majority of the books attributed to Krishnmurti, The First and Last Freedom is edited from talks he gave and discussions with attendees. It emphasized the importance of not identifying with belief systems, whether spiritual or political, but, instead, maintaining an unclouded mind – what he called “choiceless awareness” or what might be considered Mindfulness now – which allows one to perceive things as they are rather than as one is taught or conditioned to believe they are.

Joe tells me, “It was like it was written for me.” As it happened, he hadn’t grown up in a household that held tightly to a religious belief system. “The family religion was that religion was the opiate of the people.”

After CCNY, Joe went to France. “I was a bit of a Francophile. I liked the French language, and I wanted to go to France. So my step-father got me a job in France using my French, which turned out was terrible and not up to speed. So I spent that summer learning more French and met a woman I was very attracted to. I was dead set on having a relationship with her and leaving my home. So I went back to New York and did another semester at City College and arranged things to be able to study in France and get credit for it toward my BA, which I did. I spent three-and-a-half years in France. And when we broke up, I decided to get some therapy, and I couldn’t find someone in Paris for some reason, but I went to England and found someone associated with Ronnie Laing.”

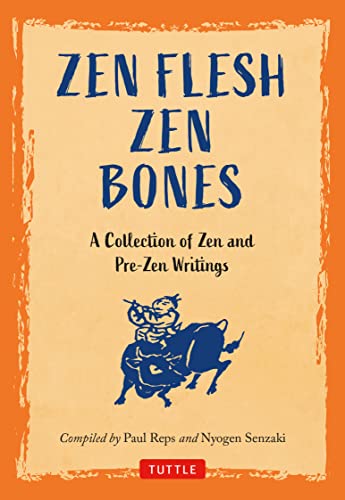

R. D. Laing was a Scottish psychiatrist whose book, The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, was popular with young psychedelic users in the 1960s. “This therapist was a poet and I think had a spiritual side to him at least at that time. And he told me a Zen story from a D. T. Suzuki book, and I was captivated by it. I think the reason he told it to me was ’cause I had seen a Japanese movie, a Kurosawa movie, and I was struck by how different it was from American movies, and I said I couldn’t put my finger on the difference. I said, ‘Well, it’s just that he has a different sense of time and space.’ And he said, ‘Yeah. Maybe “no time,” “no space.”’ And that was another one of those moments from non-Buddhist therapists who have actually said some very Buddhist things even though none of them have been Buddhists. So that got me going on a walkabout to North Africa before I returned to the States. A month in the desert; a month on the seashore. And in the desert I had some interesting experiences. I didn’t know it at the time but that would lead me to Zen practice, because my next stop was Hawaii where my sister was living. And down the road from where she lived was the Maui Zendo. So I went there and saw this man who was gardening. Asked him what they did here; I’d heard it was a meditation center, and he talked to me about it in an easy-going matter-of-fact way. So I decided to go on Saturday for a sitting, and there he was dressed in all the Buddhist finery and leading the chanting and the walking and so on. And eventually I became his student.”

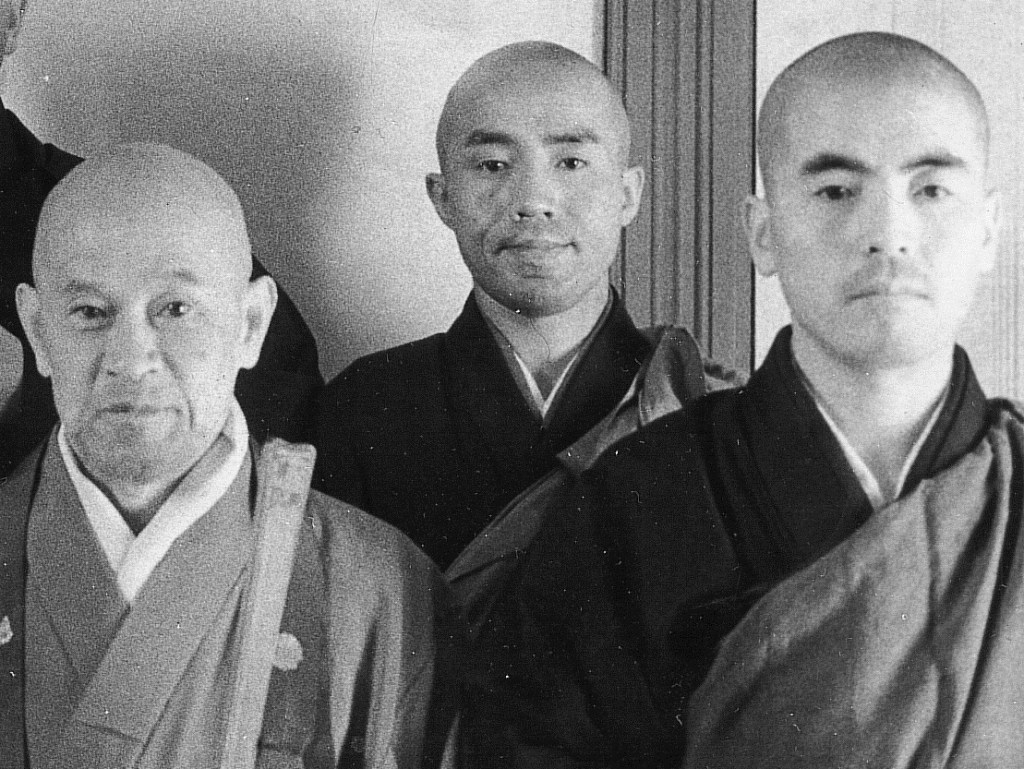

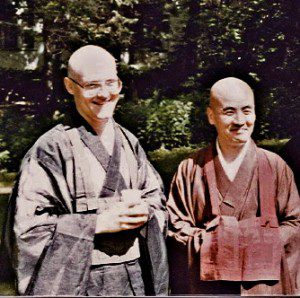

The gardener was Robert Aitken, recognized by some as the earliest North American Zen “ancestor.”

When I ask Joe when Aitken was like, he tells me a story:

“So I guess this is 1972, and at that time he was writing a series of talks on beginning Zen practice, which would later become Taking the Path of Zen. So he would invite all new residents – people who had moved in – to come to his study. This was a house, and it had like a walkway out in the back, and off of the walkway was Anne’s office – his wife – and his study. And so he’d invite students there, and he’d read them his latest chapter. And I remember the first time that I got there, I was dressed in cut-off jeans and a tank-top, and I had walked from my sister’s place which was about a mile. And this was Hawaii, so it’s hot and moist and so on. And I get in there, and he said, ‘Next time, why don’t you wear pants and a shirt that covers your shoulders and – you know – have the clothes be clean.’ I thought that was a bit of an imposition. So I said, ‘But I thought that all beings by nature are Buddha.’ As if to say, ‘Why do I need to dress up?’ So he thought long and hard – he was kind of green at that time – but what he said stuck with me. He said, ‘Sometimes, disorganized outside, disorganized inside.’ And I thought to myself – later, you know – little did he know just what a chaotic mess it was inside.”

“Why did you stay there? At the zendo?” I ask.

“It was the sense of community. I was kind of a lost boy, having had a father who had left when I was a baby. Yeah, I was looking for – in retrospect – a father and steadying and a practice to help me with my mind, and a path. So it provided all of those things. It was a lay center, which was good, so there wasn’t a dichotomy between priests and laymen. There was a kind of a radical equality. And Bob – as we called him in the day – and his wife, Anne, were like surrogate parents to all of the students. So having a sense of meaning, having the opportunity to work, to edit our newsletter, to cook, to have a kind of a holding environment, what Erik Erikson called a kind of ‘moratorium’ between youth and adulthood was very important. All of it. And practice was difficult. I had injured my hip, so I sat on a bench or a chair and the practice was painful, more painful than it would normally be. But I appreciated dokusan. I appreciated the give-and-take which is very frequent in our tradition. I thought I could duplicate the experience I had had in Morocco, and I’d be sort of ahead of the game. But it didn’t work like that at all. I had had a real experience, but we started from the beginning, and I realized how much I had yet to let go of and growth I had to make. But there was something in the practice itself as well as the setting and the sense of community and it being sort of an occupational therapy center for a number of us, like – what do they call the places when you get out of a hospital? – like a halfway house. It was sort of a halfway house. There was something about the practice – both zazen and koan practice – which I took to. Roshi was also politically very progressive. I don’t know if he was ever a card-carrying communist, but he was a card-carrying anarchist in the true meaning of that word, and that sat well with me. We talked the same language. And he had a little bit of psychological awareness. He knew how wounded he was psychologically. He was maybe the first Zen master to write about Zen and psychotherapy. So he knew it was an up and coming thing. And even though I was not a therapist yet, I had those inclinations, so I think that also made me feel at home.”

I ask about the Morocco experience.

“Well, I was staying in a little town just inside the Sahara Desert, a little oasis town, practising yoga, cooking, doing a little bit of writing. And I liked the nights. The days were hot; the nights were cold, and I’d walk out, walk along the dunes. And here I went to the top of this dune and was sitting there, and the stars in the desert feel like they’re right in your face, and the light was just throbbing. I had an experience of . . . Difficult to put into words. But an experience of gratitude and openness and connectedness with the vastness of the universe – let’s put it that way – with the dunes and the stars and everything included.”

“And your parents – whose religion was that religion was the opiate of the people – how did they react to you getting involved with Buddhists?”

“Well, I didn’t grow up with my biological father and didn’t see him until I met him years later. So he wasn’t critical. But at one point, I went to live at a school nearby the zendo that the zendo was sponsoring and I took over that school. It was an old Mormon church which had been converted. I assumed the reins. And after I met my father in California, he came to stay with me briefly at the school.”

“When you say you took it over, do you mean as a school or a residence?”

“I became the school director. I’d always wanted to start my own school. It wasn’t a Zen school, but it was sponsored by the zendo. It’s actually an interesting story of how I brought the two together in my mind. So my father didn’t say much about it. He’d poke fun at my healthy food habits, but he never directly commented on Buddhism. My mother only minded it because I hadn’t returned to New York after the family reunion that had brought me to Maui. But she visited Maui often, and one time she asked to come up and have lunch. So she had a silent lunch, and this lady who is not open in a Zen kind of way, she later said it was the most relaxing time she had ever spent. She really enjoyed the silence. So she was understanding – let’s put it that way – of my interest in Zen.”

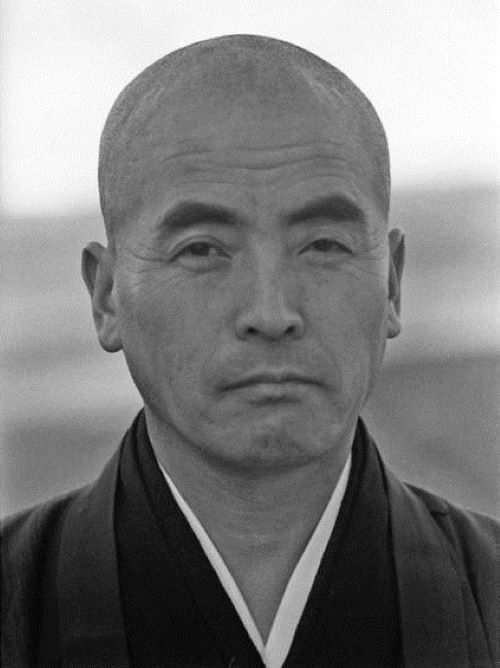

I ask Joe if he worked any teachers other than Robert Aitken.

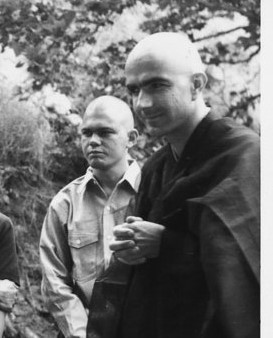

“Primarily Aitken Roshi, but in the early days Yamada Koun Roshi – who was was Roshi Aitken’s teacher – would come to Maui, and he was a very special teacher. So he was also a teacher of mine. And then after about ten years with Aitken Roshi, I met Thich Nhat Hanh at a workshop at Tassajara – actually accompanying Roshi there – and I spent two long summers in Plum Village before it got crowded and had the benefit of being close to Thich Nhat Hanh, translating some of his work. And I have to say that really impacted me in my practice and in my teaching in a really good way. I did stay in Hawaii and finished formal studies with Aitken Roshi and actually came back to the mainland, gradually began to teach as an apprentice and then – you know – in 1997 received Dharma transmission.”

“What’s the purpose of Zen. What’s its function?”

“Yeah.” He pauses a moment, and then says, “It’s to brush your teeth and change your undies.”

I may have sighed. “It’s hard to get a straight answer to that question. I think I’m gonna stop asking it. A cousin comes to visit you. You’re her favourite cousin, but she’s just a little concerned that you’ve gone off the deep end. And she asks, ‘Joe, what’s this all about?’ You probably don’t tell her it’s about changing her underwear.”

“Well, one thing I could say is – you know – Tibetan Buddhism has become very popular in the West. And when it was overtaking Zen in its popularity, someone asked me why I didn’t study Tibetan Buddhism. I said, ‘I realize now that one of the things that drew me to Zen practice was that I had a very busy mind.’ And so it really is a delight to not be in the grips of a very busy mind. Not to be caught up in thinking.”

“Why would that be a good thing?”

“Feels good. Yeah. Sort of very open to the world, open to nature. Calmer. Less self-absorbed, self-preoccupied. More open to the world and its joys and sorrows. And it allows you to develop a focus through which you can understand existence a bit more directly, more deeply.”

“Is that why people come to you as a teacher, because they have busy minds?”

“A lot of people do.”

“Do they ever come because they’re motivated by a desire for awakening?”

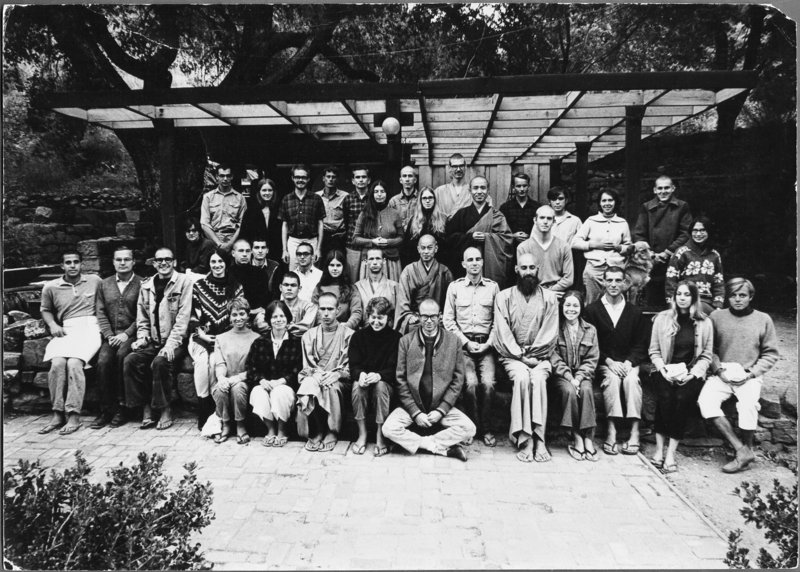

“Not as often as in the old days. We were a unique crop, that Age of Aquarius. I think some people do. And some people come for one reason, and then they get the passion, and then they see what else is possible, and they may want to go deeper. At this iteration, in my teaching in Los Angeles, there are few people who have that motivation like we did back in the day. That was a unique period of time, and I don’t think it’s been duplicated.”

One of the things that motivated me to interview Joe was the Coming Home Project he founded to help veterans, their families and care providers “alleviate the psychological, relational, and spiritual injuries of war.” He tells me the idea first came to him while he was walking along a beach with his mother.

“First of all, 9/11 had a great impact on me. I had a dread that we would go to war. And we would not use it, and use our moral capital from it, in a constructive way. That we would not build true strength, which is found in alliances and is found in collaboration with other countries. And I was afraid that we wouldn’t see it as simply a police operation to find a bad guy and bring him to justice, and, in doing that, enlist a lot of cooperation with other countries who were very well-inclined towards us. We’d just go off to war, and gradually I could see that happening. And a number of us – a number of spiritual teachers – would demonstrate along with the large demonstrations that happened all around the world before we invaded Iraq. And I saw they weren’t doing anything – all these demonstrations – and they wouldn’t do anything because we were dead set on going to war and I felt very frustrated. Grieved and aggrieved. And the other thing that was happening was that the veterans were coming back, and the suicide rate was astronomical; they weren’t getting the help they needed. The families weren’t even addressed at all. And I thought one day – and the first person I told was my mother while we were walking along the beach – I thought one day, ‘Hold it a second! What’s needed is for them to have a place to come, to heal. They need a kind of retreat.’ And I told my mother, ‘I know about retreats.’ First of all, I lived at Plum Village which originally was a retreat, a community for traumatized Vietnamese people led by Thich Nhat Hanh. I’d led many, many sesshin. And I had also done a number of interdisciplinary retreats about psychology and Zen with large numbers of people. So, why not me? And so I developed a retreat format and got to work and got a couple of people to help me, and put some money down of my own. We got a couple of $5000 grants, and we had our first retreat in 2008. About forty people from all around the country. Family members and veterans. And a psychologist who had done some work for the Navy told me, he said, ‘If you ace this, they are going to be banging on your door, and you’re gonna have a problem. You’re gonna have to beat them away. And if you fail it, no one will ever come. Word will get out immediately.’ And we apparently aced it. And by the second or third retreat, we had upwards of a hundred people coming from all around the country. And then we got a grant for almost $2,000,000 so we could do some serious damage. So that’s how it began.”

“Is it a Zen program or a psychological program? Or a combination of the two?”

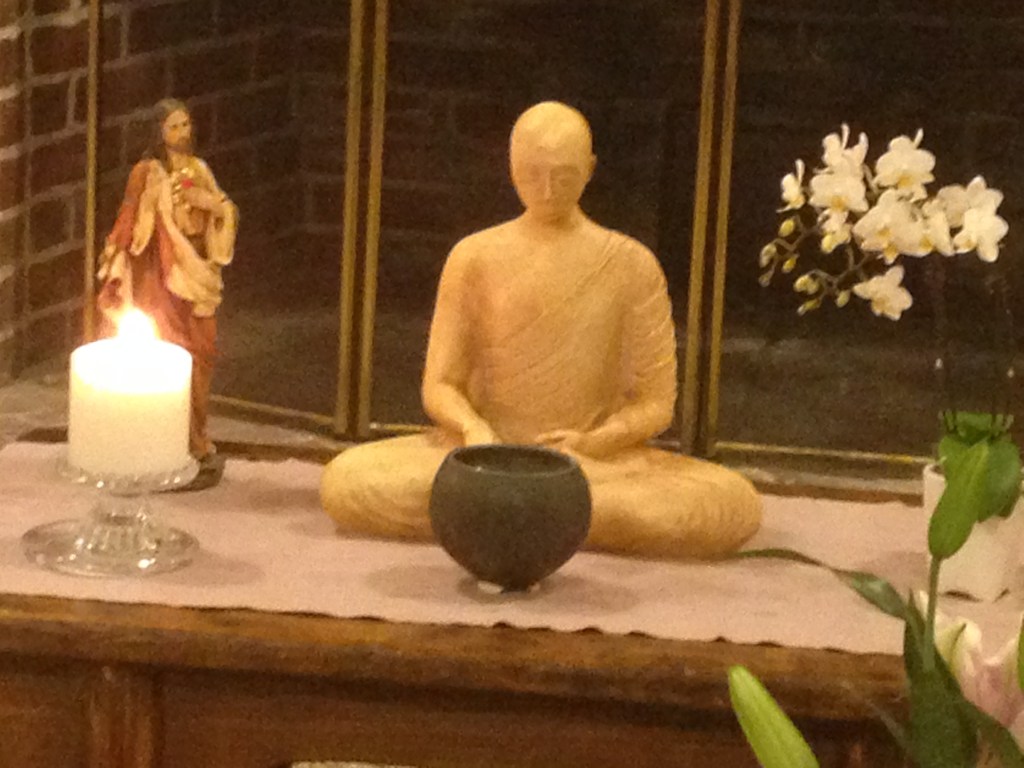

“What I said was, ‘It’s therapeutic, but it’s not therapy.’ And it has nothing to do with religion, with organized religion. Almost all the people who came to our retreats came because it had nothing to do with organized religion and it wasn’t therapy. They didn’t want to get their heads shrunk. But it was obviously informed by what I learned about safe settings and what makes people feel safe to open up to process their trauma. It was informed by my Zen practice. Not only in that we had wellness practices including meditation, but by my understanding that of the Three Jewels the most neglected and maybe the most powerful one is the sangha. I started out saying ‘unconditional acceptance, unconditional welcome,’ and finally I realized that this is unconditional love that we were providing in a setting which accepted people where they were, no matter what they’d done or countenanced. And included their whole family. They didn’t know that I was a Zen master, that I was a psychoanalyst.”

“Do you still take Zen students?”

“Yes.”

“This is the Deep Streams sangha?”

“Deep Streams Zen Institute.”

“Oh? Why ‘institute’?”

“I called it an institute because beginning in 2000 we got non-profit status, and I wanted to be able to apply for grants for a whole variety of programs. Eventually Coming Home Project. I didn’t know I was going to do Coming Home Project in 2000, but I knew I was going to do a series of interdisciplinary programs on Zen and different elements in psychology. And I did. We did maybe fifteen programs, two of them big retreats on Zen, psychology, what’s called Interpersonal Neurobiology. Stuff like that. I was developing a conversation basically, taking Zen out of the priestly realm and into the cultural commons with other healing traditions. It was a conversation about similarities, differences, and so on. So that’s why I called it an institute in the beginning.”

“Do you still meet in person or are you one of the groups that moved online after the pandemic?”

“We moved online, but we occasionally have in-person retreats and social get-togethers. Sangha get-togethers.”

“Any crossovers? People who come to you as a therapist and do Zen?”

“No crossovers. I’m very clear about that. We start one way, we stay that way. If you want a Zen teacher once you’re in therapy with me, I’ll refer you to a Zen teacher. I think it’s very important to keep them separate. I know there are people who don’t, and I think it leads to problems.”

“What is it that you hope for for the people who come to you to take up Zen?”

“Hope for them? I don’t do too much hoping for my students. I just take them where they are, work with what they present to me, and try to stay true to their motivation. Sometimes I will invite them, through things that I say, to consider things at a deeper level. Some work on koans. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re accessing a deeper level.”

“Yeah, you can learn how to answer them – get the formula right – without really getting anything from them.”

“Unfortunately, that happens too often. I still use koans, I still value koans, but I agree with you. And so it’s a tricky thing. And there are some people who have their own kind of opening without ever using koans. I’ve seen this happen with several students of mine. Where just-sitting, for example, doesn’t become just a technique, but it becomes just-sitting! Just like just-walking. Just like just-swimming. Just like just-dying. And it’s kind of remarkable that they didn’t work with a koan. So I hope they find some measure of peace in this life. I hope they become intimate with something vaster than yet including themselves.”

“So you do have something you hope for them. Let me flip it. What do your students hope from you?”

“I don’t know what they’re hoping from me. I listen to what they’re hoping for from Zen practice.”

“Fair enough. What are they hoping for from Zen practice?”

“It varies. There’s the one lady who hopes for reduction in her medical symptoms. Someone working on chronic anger that makes them sick, that’s threatening their marriage. Some working on overwhelming emotions. Some working on understanding themselves better.”

“And what do they see your role in all this? Are you a priest, a minister; a cheap therapist they don’t have to pay by the hour; a coach?”

“I’m none of those with my Zen students. I’m a Zen teacher, and they learn what that is over time. If somebody wants to become my student – not everybody in the sangha is my student – but if someone wants to become my student, then they need to practice on a regular basis, come to all our retreats, invest in our relationship, and clarify their motivations such that it is to put themselves in accord with the Buddha Way or” – he smiles and chuckles gently – “learn why Bodhidharma came from the west. They need to fulfill those conditions to be a student. And we meet regularly. There are a fair number of other people – I think maybe half the people; sometimes more – who come and they see me as their teacher, hear my talks, attend dokusan. We each learn from the other, our interactions, who we are as people. How I interact with them. How I face challenging issues. How I respond to their questions. So they get a sense of who I am. And how we work together. They seem to get something out of coming around. But the main thing is we’re investing in each other. I’m investing in their spiritual well-being, and they’re investing and trusting me as their teacher. It’s up to me to live up to that trust.”

When our time is drawing to a close, I ask if there were anything he’d like to talk about that we hadn’t covered.

“Only maybe the school that I started in Hawaii as part of my Zen practice. At that time I had already worked with kids for many years. So I started this school with a couple of other zendo residents. And I wondered what would be Zen about it? Because I didn’t want to have it be a Zen school, but I wanted it to be Zen infused, Zen informed. And what I realized then was that there were a few words that all began with ‘C.’ One was ‘creativity.’ Another was ‘compassion’ and ‘consideration.’ And another was ‘courage.’ The courage of your convictions and to have a voice. And I thought we infused that school with those qualities. And the kids loved the school. They just loved it. The other thing that I would do was do Zen-like kinds of things with them. Like, before we’d have lunch, I’d say, ‘Let’s all be as quiet as we can and see how many sounds we can hear, and later we’ll talk about who heard the most.’ And now I’m starting to work with one student on the koan, ‘Who hears the sound? Who is the master hearing that sound?’ Or just, ‘Who hears?’ So I didn’t know that koan at that time – we weren’t using it in our lineage at that time – but the kids loved it. It was the only time of day when there was actually quiet in the room. As you can imagine, a bunch of toddlers and nursery-school aged kids. And so that was a blessing. That was a beautiful time, that school. And it set the stage about how I thought about some of these interdisciplinary educational programs, and some of the healing programs which were interdisciplinary as well.”

“Isn’t that how the Aitkens met, at a Krishnamurti School?”

“It was.”

“Did they have any input into what you were doing?”

“None. But they loved it. They were very supportive of it. And, yeah, Anne was the Assistant Director at Happy Valley School, and Roshi was a teacher, and that’s where they met. And it’s very interesting that Krishnamurti – independent of Roshi – had been my first inspiration along the path.”