Dai Bai Zan Cho Bo Zen Ji, Seattle

The first ancestor (patriarch) of the Chinese Chan tradition was the Brahmin monk, Bodhidharma, who is credited with bringing the teaching to China from India. The opening koan of the Blue Cliff collection describes his meeting with the Emperor Wu, estimated to have taken place around the year 520 CE. After that meeting, Bodhidharma was said to have retired to the recently established Shaolin Monastery located in the Songshan Mountains. The monks there were engaged in translating Buddhist scriptures and spent long hours doing so. As a result they were in poor physical condition, so Bodhidharma taught them a martial version of traditional Indian yoga, which evolved into Kung Fu. The Shaolin Temple is still active and claims to be the birthplace of both Kung Fu and Zen.

The connection between a religious tradition generally considered pacific and martial arts was furthered in Japan where Rinzai Zen became the de facto religion of the Samurai classes. This came about because Rinzai Temples were assigned the responsibility of providing schooling for young males (and it was exclusively males) of the nobility. Because the students were housed in a monastery, they were compelled to take up meditation practice, and one supposes they were not eager to do so until they discovered that it enhanced their swordsmanship, something they were eager to develop. The relationship between Zen and kendo – the art of the sword – is so deep that one third of D. T. Suzuki’s Zen and Japanese Culture focuses on the subject.

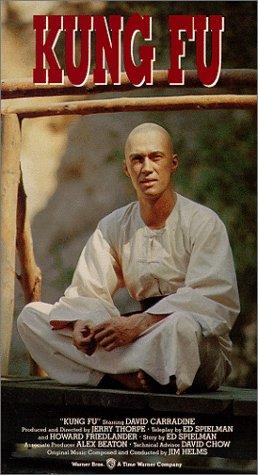

The relationship between Asian monks and martial arts became embedded in Western cultural consciousness through films and television programs such as the 1972 series, Kung Fu, which followed the exploits of an exiled Shaolin monk in the American west of the 19th century.

“Every once in a while, my wife and I think of an old TV show,” Gendo Testa tells me. “You can find any old TV show and go back and watch it, and sometimes it opens up a portal in your being. So we watched the first episode of Kung Fu, and my wife was like, ‘Oh! I can see your soul!’”

Although I interview Gendo shortly after he had been ordained an Osho at the Chobo-ji temple in Seattle, much of our conversation focuses on his engagement in martial arts.

“And I was like, ‘Holy shit! I really took this in!’ So the whole Daoism, the monastery, the martial arts, the integrity, the honor, the hero, the ‘standing up’ was all in there, and I took it all in. I was just a kid watching a TV show, but there was a whole lot going on.”

He was nine years old at the time.

“That was your introduction to both Buddhism and the martial arts?” I ask.

“Yeah, I think they’re sandwiched together and that was the influence of the show. It was about the transformation you see him go through. That potential, the human potential of going through something like that. The relationship between him and his teacher. These are all things I longed for in some way or was attracted to. When I ordained, I was asked to give a short Dharma talk and in it I was aware of a thread and it went all the way back to not only the Kung Fu show, but to memories of my dad taking me to international food festivals. And one in particular was at Brown University, and it also had cultural performances or arts. And the one from Japan had kyudo, Zen archery. Mmm! That was something. The way the man came out. So dignified. His posture. The way he pulled one sleeve down and dropped into seiza so perfectly. The whole thing. And everyone got quiet as he drew that bow. And when he finally released the arrow, something special happened. It was like a ‘What is this?’ moment. I felt something. I felt he had a power and a clarity that I’d never seen in real life, something I’d only seen – I guess – on television. But yeah, I was really into that Kung Fu thing. I remember that even during the commercial breaks, it was winter, and I’d go outside in my bare feet and just try to walk like he did in the snow. But that moment of seeing the Zen archery, that was when I felt like, ‘Okay! That’s it!’”

Although he describes himself as a “bit of a scrapper” as a young person, he didn’t take up serious practice in a dojo – training studio – until he was in his twenties.

“I bounced around a few styles and got pretty proficient at fighting. I had a fighting spirit. Not because I . . . I don’t know.” His voice becomes softer more reflective. “I had a quality that got me into situations. Always standing up for someone else. Even when I was really small, I got my ass kicked a lot for standing up for somebody else even though I wasn’t big enough to defend them or myself. But eventually I got the hang of it.” In one case as a child, he beat up a local bully so badly that he had to have medical attention. Gendo’s parents were required to cover the bills.

“My dad was upset, but it was unusual behaviour for me. And when I told him about what had happened, he said that ‘You need to get better at knowing when to stop.’ I think that’s why I was always in and out of dojos. I was hopeful that I would find an environment that would help me transform.”

“Transform in what way?” I ask.

He smiles shyly. “What my image of a martial artist was, someone who had come to terms with . . . Well, they’re strong, but they also have gone beyond the need to prove it. I believed the dojo I was looking for was only to make me a better person.” He describes the early martial form he learned as an aggressive blend of shotokan karate, uechi-ryu, and jiujitsu. It could be effective, but as he puts, it only provided him with hammers.

He didn’t find the form he was looking for until he was in the 30s.

“I had started a new job, and there was an aikido dojo near the job. And they had an early morning class. I had kids, and Dad’s just got to get up earlier if he’s going to do anything for himself. So that’s what I did. I started the morning classes, and these were the teachers I needed. They were all police officers. Real no nonsense guys. They had all done other martial arts, and they were really good men. And their aikido was very strong and clear. And as soon as I met them, they kind of drew me into their circle because I was very dedicated to my training. And pretty much early on they said, ‘You’ve got to meet Toyoda Shihan. He’s coming out in a few months; we’re hosting him.”

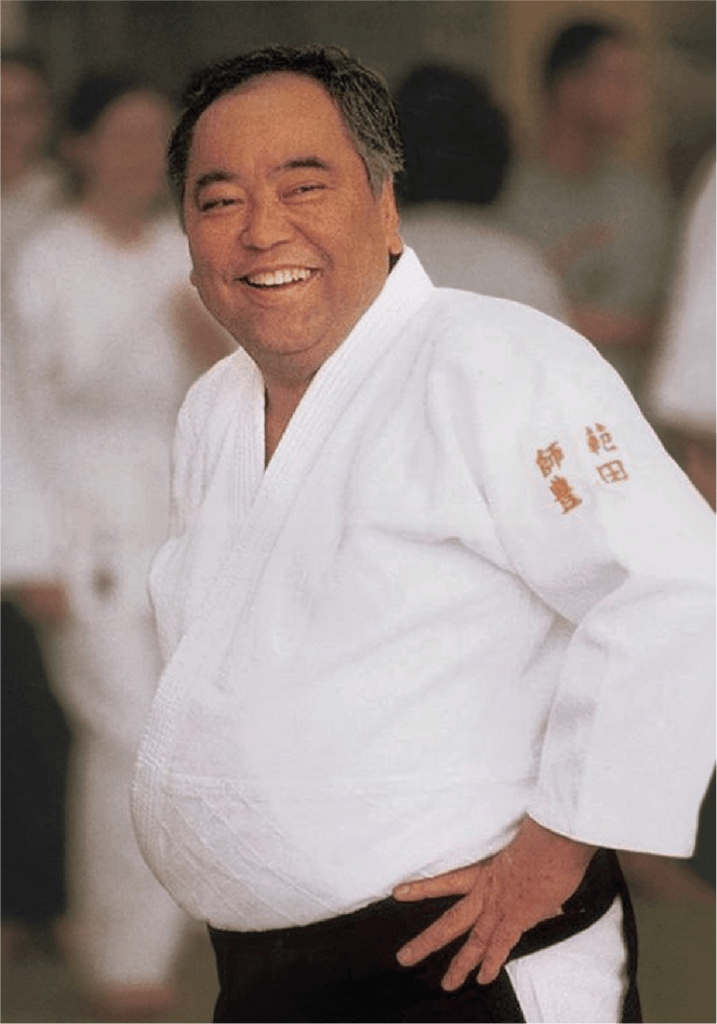

“Shihan” is an honorific used with martial arts instructors suggesting a higher rank or authority than the more common “sensei.” Toyoda Shihan was Fumio Toyoda, a Japanese-born Aikido master whose practice was grounded in Zen. Gendo was assigned to be Toyoda’s attendant for the weekend of the seminar.

“So I had to pick him up at the airport, get him to his hotel, and drive him around for the weekend, and I got to know him. I didn’t have many years with him. He passed away within five years of my meeting him. But I absorbed him a bit. In aikido, you’re looking to harmonize or blend with the attack and lead it to a neutral point so you can take the balance at that point and throw or pin them. And to get skillful at it, you need to learn how to change how you hold your body. So you’re looking for fluidity of movement. You learn the essence of the technique through receiving it. Once your physical abilities are at a level where you can stay connected and ride the wave – so to speak –you’ll eventually get this ingrained feeling of what the techniques are. And so I was terrible at technique mostly because my previous training had been stopping everyone’s attack. So I threw myself headlong into this training, to receive, and I got good at it because I wasn’t afraid to take the falls. I knew these guys weren’t trying to hurt me, but they could throw really powerfully. But aikido’s set up in a way that you’re throwing the person in a way that they can fall safely as long as they’re attuned and as long they don’t try to get in the way of where you’re throwing them. You temper your body that way. And you’re getting up off the floor over and over. It’s a very different way of training your body. So, anyhow, I was good at that. Especially for a beginner. So sensei used me a lot, and I got a little closer to him for that reason. And he was really kind to me. And he was insightful. I knew he looked at me, and he knew what to do with me. I think now I know because I was him in some way. I didn’t know it until he passed away that he was a scrapper too, that he would stand up and fight if necessary. So I think he knew what to do with me. And he’s the one that encouraged me to sit zazen, which I hated.”

“So he was the first Zen Buddhist you met.”

“Yeah. He’s the first Zen Buddhist I met. He emphasized that aikido training was shugyo. Shugyo is intense physical and spiritual training to be used for self-transformation. He would say that if you wanted to really learn his aikido you would have to sit zazen.”

“Which you hated.”

“Oh, yeah! Hated it! Well, I still didn’t have what I’d call a non-negotiable practice, so to speak. I’d get on these kicks and not be able to stick with it. It’s hard to sit by yourself. But I feel like the dojo itself was meditation. Being in the dojo, because of the concentration needed, I didn’t think about anything else. So in some way, just going to the dojo and being in a training environment, you’re there for a couple of hours not thinking about anything else. And then leaving the dojo and slowly your mind comes back. You know? The wheels start spinnin’ again. And so I was aware that the dojo was medicine for me all along. And that, I think, was enough medicine for a long period of time. I needed tempering, and, honestly, it looked like that was a decade of tempering.”

Then his family moved to Connecticut, where he learned about Robert Heiwa Burns.

“He had an aikido dojo. So I went to visit him, and he was a little volatile. A pretty fiery guy. But also very passionate. He had a place called Aiki Farm; it was an organic farm where he grew greens and sprouts. And he took his jukai under Genjo Marinello Roshi. He was also a former Marine and political activist. When I met Heiwa, he was in his 70s. So from my house, I could walk through the woods, cross a road, and there’s the dojo. I started to go there in the mornings. And we would sit zazen. We’d do forty-minute sits, and then we’d do aikido. We were only sitting like four times a week, and eventually I felt I needed to commit to this because I can’t go to bed so early four nights in a row and then not do it the next three. So I asked him, ‘Can we just sit every day? I’ll show up. Don’t worry about anybody else.’ So we started doing that. It was a thing every day for years.

“So Heiwa only had a handful of students, and he had this organic farm, and we’d help him plant. But one summer we didn’t have enough people to harvest everything we planted, so I suggested we do what’s called shochugeiko, which is a summer intensive practice. It used to be held in Chicago in July, but I convinced them to let us host it here on the East Coast so we’d have people to help harvest. So I pitched the idea to Heiwa. He loved it, and a few days later he’s like, ‘You know, I called Genjo Roshi and asked him if he’d come out on the last day, and we’d just sit all day.’ And I thought that sounded like a good idea. Like, ‘All right. We’re going to have a Zen Master come in. It’ll be great.’ Right? It was a terrible idea. By the time Genjo came in, we were in rough shape. The heat! It was a gruelling heat, and we were training hard. This was a hell camp, something you don’t go to unless you’re prepared to go to your edge, unless you’re prepared to fall down from exhaustion. So we ran everybody hard. Then Genjo came in, and I’m pretty sure Heiwa told him, ‘Hey. All business.’ So he came in, and, before the end of the morning, we had done more sitting than we had all week. Sit after sit after sit. I’d never done a zazenkai even. None of us had any experience with that. So it was rough. We didn’t have much form. We chanted the Heart Sutra. We had somebody be tenzo. We had two jisha – people serving tea and cookies – other than that, there was no Dharma talk, there was no sutra chanting; we didn’t know any of the sutras. So it was brutal. And it wasn’t until I drove Genjo Roshi to the airport after it that we really kinda clicked. So that’s how I met him. And then I think we brought him out the next year, but we did a longer sit, and we did it before the camp. A mini-sesshin, Friday to Monday morning. And then the camp started, and we did that for a whole week. And that was better than the opposite way. And by then I’d been sitting very faithfully for a year, and it was easier.

“But I still didn’t have a good experience until two years later. My bodywork sensei was Everett Ogawa, who’s the founder of Integral Bodywork. It’s a form of structural integration. I was training with him, and he was based in Chicago. And at a certain point I had gone through, like, the first level of training. I’d got my certificate that said I had completed the ten-session training. And he was like, ‘I can’t take you further unless you go to sesshin.’ I was like, ‘Uhhhh [sighing]. . . Really?’”

I tell Gendo I don’t know what Integral Bodywork is.

“So Structural Integration is a series of ten different sessions that slowly work the connective tissue in the body. The idea is to bring it into a vertical alignment. So the first session is releasing the breath, the rib cage, and diaphragm, and that frees up a whole lot of vital energy. And that vital energy is gonna want to be grounded so it’s gonna move into your legs. And the second session is releasing the feet, the legs, so that there’s more of a vertical lift through the legs. And since you’ve opened your rib cage, your legs kind of lift everything up. So now you’re more open. And then it just continues. We keep continuing the freedom to move somewhere else. It gets bound up, and we keep helping it get free. Eventually the body gets into a vertical alignment. Like if I stand naturally,” he stands up to demonstrate, “my body weight is more on my heels. There’s a clean line between my ear, my shoulder, my hip, my knee, and my ankle. I didn’t start off that way. But over time you keep looping these sessions, and if you keep doing that, your body keeps opening up.”

“Okay, so why did Everett Ogawa see a connection between that and doing a sesshin?”

“He had done many sesshins himself, and he felt that a daily sitting practice and attending sesshin were essential to revealing your life’s purpose. He said the same thing about the bodywork. They both were life altering opportunities to surrender and release. It occurs to me now that if we envision a person sitting perfectly in zazen, that perfect posture is a body that’s in a vertical alignment.”

“So all along, it was your interest in martial arts that was driving your practice,” I say.

“Yeah, but I needed that. I needed the movement, the physicality of it. Also I had a reverence for the aikido dojo. I really liked the etiquette. And I never felt that before in any of the other martial arts I did because they were kind of Americanized. So I felt that my aikido experience was the most pure thing that I had done.”

Eventually Ogawa suggested he attend a sesshin at the Blue Mountain Zendo in Pennsylvania. “He said, ‘I need you to do a week-long sesshin, and then I can train you more. It’s really important. I really want you to do this.’ I said, ‘Okay.’”

“But again,” I point out, “your reason for agreeing is because of the martial arts.”

“Yes. Yes! So I get sent to Pennsylvania. And it’s Ryuun Joriki Baker Osho.” Ryuun Baker had received authorization to teach from Genjo Marinello. It was Gendo’s first experience of a formal sesshin. “They had a small group, but they had the posts covered, and I’d never seen a densu [chant leader] before. I’d never seen anybody hit the han. There were all these new things. I’d never done the meals oryoki. Never done that. And until then I had only done enough sitting to where you really don’t break through. Two day or three days isn’t enough. You just go, ‘The pain has ended. I get to go home now and have a beer.’ So that was the first time I was in a situation where I got past that. And that sesshin was very . . . Productive isn’t the right word. But a lot of things lined up for me.”

Over the next few years, he remained committed to both his Aikido and Zen practices, and then he went through a period of what he calls “great duress.”

“A family crisis involving a beloved person. I was unable to sleep and was filled with dread and worry night after night. Around the tenth day of the crisis, I attended a guided meditation. And during it there was this feeling in the lowest part of my body, deep in my belly. It was like a spinning feeling. Like an uprootedness. Honestly, I really thought I was dying and that whatever my essence was was going to leave. I felt like my insides were rising up. It was peeling away.” He goes onto to describe a dramatic experience of a buildup of energy which felt like it shot up through the top of his head, and he had a sense of “leaving.” “Throughout this entire process, I’m saying goodbye to everybody – everybody who loved me; everyone I loved – and I tell them that I’m sorry, but I’m too tired to stay. You know? I’m too tired to stay. And then it stops, and everything’s super quiet. I mean, no internal dialogue. Nobody in my head talking. Nothing. And the world is super clear. And I get up, and I’m like, ‘I need to get outside.’ And the trees were not ordinary trees. The moonlight was not ordinary moonlight. And I’m captivated, and I’m bristling with energy. This really pure, clean energy.”

The experience had taken place in 2006, but he didn’t speak about it to anyone until he finally attended a sesshin with Genjo in 2011 and brought it up in dokusan. “And he just leans forward with kindness and puts his hands on my shoulders, and says, ‘We’re brothers in the Dharma.’ Then he asked, ‘What did you do with your life after that?’ I said, ‘Well, I left my job, and I started a non-profit.’ I told him about my three vows. I didn’t have four. Didn’t know there were four. To no longer make fear-based decisions. To do what my heart says is correct. To be of service to others. Genjo then said that I was already living a life in the Way and that I didn’t necessarily need Zen training, but that it could be just the thing to bring me to great maturity. Those words ‘great maturity’ stuck with me. I remember driving home from that sesshin and blurting out. ‘I am going to do that again!’”

Shortly afterwards, he took jukai because he wanted to commit himself to doing at least two sesshins a year, which in the Chobo-ji system is one of the requirements for jukai. Then Genjo suggested ordination.

“And I go, ‘I don’t know. I don’t feel priestly. I’ve got all sorts of hangups about priesthood.’ But he’s like, ‘Consider it.’ And he asks me to read your books. ’Cause I don’t read Zen. I’m all about the experience, right? So I really don’t have too many Zen books except yours. Your books are the ones that got me to meet the ancestors and go, ‘These guys are a little whacky. I like these guys.’ There was just something there. It just showed me that what I thought Zen was, it wasn’t. I didn’t really know what Zen was. So I needed more time to start doing deeper koan work, ’Cause that’s when you really get to know them. At any rate, Genjo felt that I had the stuff. And that was important to me. I’m a teacher, and sometimes someone comes along, and you’re like, ‘Oh, can I pour this into this vessel?’ And I could feel that from Genjo. And we just had a good connection. And I wanted Genjo in my life. I wanted an older, wiser Dharma brother in my life. I wanted someone to go, ‘Yeah, you’re doing all right.’ Or, ‘Ehhhh, let’s get you back on track . . .’ It was like, ‘What would Genjo do?’ is a big deal for me.”

“There are responsibilities associated with ordination,” I point out.

“Yes. Well, it took me a couple of years to face that.”

“And you have Zen students you work with now?” He does. “So, from your perspective, what is your responsibility to them?”

“Well, because I have so much to teach about awakening the body, that is really important to me.”

“Are all of your Zen students also involved in bodywork?”

“So far, yes. It’s just the way that worked out. Because they met me wanting the bodywork. And I happened to be a monk, and ‘Hey, sitting will help your process.’ So what’s important to me is making sure that they have control of their breathing to the point where it starts to change their physiology. I want them to have a good, clear connection to ground. I want them to be able to sit and generate energy, not be asleep, have their eyes open. Because otherwise you’re just being pulled into an inner landscape. You’re not generating a charge. So to me, that’s what it’s about. If you have control of your breathing, and you have this peripheral vision thing going on, and you’re not going inside your head, your body’s relaxing, you’re in an upright position, you’re going to generate energy. Or, I should say, you’re going get into a flow state. And if you get into a flow state enough, it’s going build a charge, and I believe that’s what leads to kensho. Enough of that charge goes” – he makes a popping sound – “and then – boom! – you have some kind of seeing through. And I think that you keep building up those charges. I really feel that’s where it’s at.”

There is a precision in the way Gendo speaks the Japanese terms associated with both martial arts and Zen, for example the way his stresses the first syllable of “aikido” rather than the second, which is how I frequently hear it pronounced. I ask him how important maintaining the Japanese envelope is for Zen in particular.

“Well, I think we want to maintain the form and not change it.”

“When the Japanese got it from China, and they changed it quite a lot, to suit them,” I argue. “Then we got it from Japan, and a lot of places seem to have kept it pretty Japanese.”

“That’s interesting too. I think I’m reluctant to take anything out of the form. I think it’s all supposed to be there. And there’s an American arrogance, too, where it’s like, ‘Oh, well. We don’t need any of this shit.’ Right? When you haven’t done it long enough to know the shit you’re talking about. You haven’t experienced it deeply enough yet. So at this point, I don’t foresee changing anything because I don’t think I know it well enough. To put it another way we need to be careful of allowing ourselves to create a practice that we find comfortable. My grandfather was known to say that if you’re comfortable you are not growing.”

Nice story

LikeLike