Adapted from The Story of Zen –

In his history of American Buddhism – How the Swans Came to the Lake – Rick Fields recounts the story of the time Rinzai master, Joshu Sasaki, gave a talk at the Berkeley campus of the University of California. One of the people in attendance asked if there were a place in the San Francisco area where one could get Zen training. Sasaki appeared to give the question a moment’s thought then said he wasn’t aware of any and suggested that if the inquirer were serious he should arrange to visit Sasaki’s center in Los Angeles.

There was a surprised, audible reaction from the audience, many of whom were students and friends of Suzuki-roshi’s San Francisco Zen Center, which by then had more than one branch in the Bay area, and Sasaki’s translator, a Japanese-American doctor, hastened to add, “The roshi means that there is nowhere else where one can study his particular line of Zen.” [Rick Fields, How the Swans Came to the Lake (Boston: Shambhala, 1992), p. 247.]

It is possible that Sasaki was making a distinction between Soto and Rinzai Zen; the Zen community in the United States, even in its earliest days, was divided along sectarian lines. It is also true, as Fields adds, that “it certainly appeared – to some at least – that the roshi had rather enjoyed the stir his blunt answer had caused.”

Sasaki is sometimes identified as the fourth of four Japanese missionaries – following Suzuki, Taizan Maezumi, and Eido Shimano – who helped establish Zen practice in America. He was two decades older than Maezumi and Shimano, although they came to the US before him, and only a few years younger than Suzuki. He had been born in 1907, was ordained a monk at the age of fourteen, and became an osho – or priest – seven years later. He spent several years at Myoshin-ji in Kyoto, which remains one of the principal teaching centers for Rinzai Zen. In 1947, at the age of 40, he was given Dharma Transmission and became abbot of a small temple in Nagano Prefecture.

According to an interview Sasaki gave in 1969, he’d had no idea of coming to the United States until two American aspirants, Dr. Robert Harmon and Gladys Weisberg,wrote to Myoshin-ji requesting that an authorized teacher be sent to Los Angeles.

Up until that time, I had no dreams whatever of coming to the United States and furthermore the temple I belonged to was so poor that they couldn’t entertain any such ideas. However, Myoshin-ji said that I would be very useful in the United States so suggested I come here. [sasakiarchive.com/PDFs/19691220_Sasaki_Interview.pdf.]

He arrived in America, reputedly, with only the robes he was wearing, a Japanese/English dictionary, a Bible, and a small valise. He didn’t waste time but began receiving students almost at once in a one-bedroom house in a Los Angeles suburb. Within five years, the group moved to new quarters in what had once been a luxurious residence on the corner of Cimarron and 25th streets. The neighborhood had deteriorated, and the building itself had been condemned by the city as unsafe for occupancy. Sasaki’s students, however, refurbished it, and it was officially opened on April 21, 1968 – Sasaki’s 61st birthday – as the Cimarron Zen Center. Later the name would be changed to Rinzai-ji. 200 students took part in the opening ceremonies.

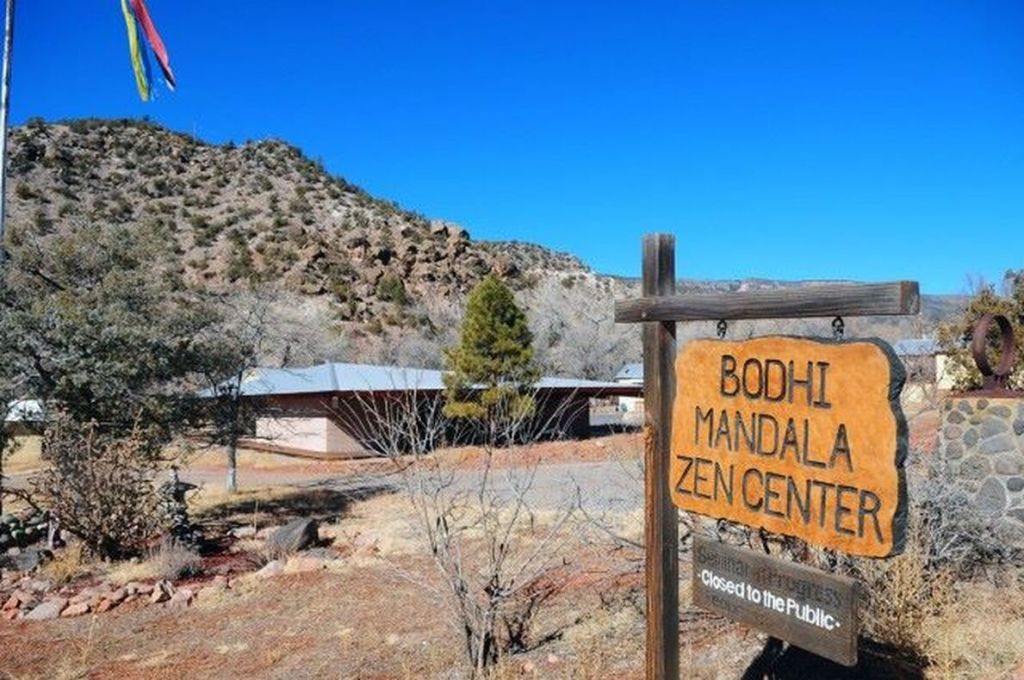

Three years later the community had sufficient funds to purchase another property in the San Gabriel Mountains east of the city. This became the Mount Baldy Zen Center. A third center – the Bodhi Manda Zen Center in Jemez Springs, New Mexico – was established in 1973. The three centers quickly acquired reputations as rigorous and austere practice centers. In a talk given at Bodhi Manda, Sasaki said: “The standpoint of this Zen Center is our own practice of Dharma Activity. Therefore we accept those who want to study Dharma Activity. Those who are not interested in Dharma Activity should leave immediately.” The training provided wasn’t easy nor for the faint of heart. Sasaki’s type of Zen has been described as Samurai. Those who couldn’t cut it were invited to “leave immediately.”

Many did. More to the point, there were others who remained and flourished. Within a few years, senior students established affiliate centers elsewhere in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Sasaki received invitations to facilitate sesshin at locations throughout North America including St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Trappist Monastery in Spencer, Massachusetts.

His students worked with koans but instead of being chosen from classical collections these were often adapted to the condition of the particular student. One might be asked how he realized Buddha nature while driving an automobile. To the monks at St. Joseph’s, he assigned the question, “How do you realize God when making the sign of the cross?”

Sasaki never acquired a very good command of English and had to make use of translators throughout his time in America, even so it was the impact of his personality which his admirers most frequently reference when talking about him. The Canadian songwriter, Leonard Cohen – who spent a period of residency at Mount Baldy in the 1990s – said that Sasaki was such an inspiring figure that were he to have been a Heidelberg physicist, Cohen would have learned German and studied physics. Cohen also admitted that he and other Sasaki students “were gravitating to teachers who were quite flawed as human beings, but that’s what we cherished. We wanted to see the dark side made bright.”

Seiju Bob Mammoser was at one time thought to be in line to become abbot of Rinzai-ji after Sasaki retired, although this never came about. When I spoke with him in 2013, I was struck by how reserved and even cautious he was when speaking except when talking about Sasaki, whom he always described in superlatives. He was “amazing” and “an utterly remarkable, unique man.” I asked in what way, and he told me, “You meet somebody who inspires you. Motivates you and moves you and demonstrates – in front of you, in his manifestation – exactly what he’s talking about. I hadn’t really met other teachers. I’d read books. I’d read Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. That was a beautiful book. But he was the first living teacher I’d met. He was sufficient. I didn’t have to go see somebody else. I knew what I was dealing with.”

Father Kevin Hunt, a member of the Trappist Community at Spencer and an authorized Zen teacher, was equally fulsome in his praise of Sasaki. “We had him in choir, and he had a room in the monastery itself. So he participated; he ate in our dining room. He gave a couple of talks to the community. There was quite a lot of interest in what he said. Basically he spoke of his experience in meditation and the Zen way of doing meditation. And, you know, a novice master had once said to me, ‘If there’s any rule in prayer it is that it will always become more simple. Less verbal.’ And so he addressed that aspect, that in Zen there’s no talking. That to speak a word in Zen is already a betrayal. And that was something that we could identify with because we had a rule of silence, and silence is very, very important in our practice. And he loved it, so somebody said to him something about coming back sometime and giving a weekend sesshin. And so he said, ‘Yes. I come back next year.’”

In fact he came back ten years in succession to lead retreats at St. Joseph’s.

He did not coddle his students. When I asked Zengetsu Myokyo Judith McLean of the Enpuku-ji center in Montreal what Sasaki Roshi was like as a teacher, her immediate answer surprised me:

“He was cruel. He was strong. He was . . .”

I interrupted to ask what she meant by “cruel” and why that was the first thing she said. She explained that she hadn’t meant it as a criticism. “I was talking with a student here yesterday, and, it seems to me, it was a very effective tool for dissolving the ego.

“The strongest teaching he gave me,” she went on a bit later, “was that he gave me a lot of responsibility.” She had been head monk of Rinzai-ji in Los Angeles in 1992 during the Rodney King riots. Sasaki, himself, was away at the time. “That was a lot of responsibility, because we were hemmed in. There were fires all around us and so on. And never any comment about ‘job well done’ or how bad it was.

“And while I was at Rinzai-ji, there was a very, very difficult older nun. She was an alcoholic. Very difficult. She used to drive people away from the Zen Center. So I was in charge of her there, and I dealt with her in an okay way. Then the Roshi turned the tables on us, and he made her the head monk. And things went kind of crazy. Like really crazy. So that was a cruel situation. And he watched and watched and no comment. He watched to see how I dealt with that. So at the time, that seemed cruel to me. But he’s just cutting off any kind of attempt to grandify oneself or to even feel competent. Because we all had something more to learn in the sense of dissolving our self.

“His methods are very effective. I mean, when your whole world falls apart, then you learn from that. And if that keeps on happening, then you keep on learning. And so if I had someone who was just kind and helped me along a little bit, that wasn’t so interesting. So I think it’s a very particular kind of character that would study with a teacher like that. I was very stubborn, but there was never a doubt in my mind that this was the person I wanted to study with, that I was glad to be studying with. No doubt. Even when it was difficult and I felt he should really give me a break once in a while, still there was no doubt in my mind.”

Others have described him as “playful,” charming, and as having an infectious laugh. He advised his students – whom he accused at times of being too serious and humorless – to practice laughing as a spiritual practice.

When you wake up tomorrow morning, first thing, stand up, put your hands on your hips, and laugh five or ten times, and that will cure you of much of your illness. This exercise is even better than a long period of meditative sitting. As a beginner in meditation, instead of suffering a long period of cramped legs, it would be better for you every morning as soon as you get up to immediately stand in this position and laugh about ten times. This is really the best beginning of Zen. If during that time you are doing this exercise and laughing vigorously, I were to ask you “Where was God at that time?“ How would you answer? Then immediately your logic and your consciousness starts to work. That is what is bad. That is time and space learning. That is not Zen. Just simply laugh and you will begin to realize. [https://terebess.hu/zen/mesterek/Joshu-Sasaki-Roshi-About-Zazen.pdf]

Myokyo’s was the ninth interview I conducted when I began this series of conversations in 2013. I had particularly wanted to interview one of Sasaki’s osho – preferably a female osho – at the time because he had made headlines in the mainstream media as a result of reports about his sexual interference with female students that had been going on for decades.

As he drew media attention, his history was examined with greater scrutiny, and it was discovered that his claim to have come to America at the request of two students in California left out a number of significant details.

In 1944, he had been the fusu – or business manager – of Zuiryuji in the Prefecture of Toyama. Eight years later, it came to light that during his time in office he had embezzled funds intended for temple renovations in order to pay for what the judge trying the criminal case against him called “a pleasure spree inappropriate for a religious figure.” Sasaki took responsibility for his actions, telling police that no one else was involved. He also confessed that “with regard to women, this is my distress as a human being.” The guards who had charge of him during his detention before trial were impressed by his demeanour, particularly the way he sat for hours in full lotus posture on his hard bed. One even obtained a zafu for him to make the posture more comfortable. He was found guilty in 1954 and served an eight-month sentence.

When he returned to his monastery, his “distress” with women didn’t abate, and it was later reported that he had fathered at least two children for whom he assumed no responsibility. When the request came from America for a Rinzai teacher, the officials at Myoshinji may well have viewed this as an opportunity to rid themselves of a monk who continued to be an embarrassment. In Sasaki’s version of the story, he performed the ceremony for permanent departure from Japan because he intended to stay in America until he had brought Rinzai Zen to the country. Another interpretation of events is that he was sent into exile.

He was, however, an effective teacher, and students were drawn to him. Leonard Cohen and Seiju Mammoser were not alone in praising him. David Yoshin Radin of the Ithaca Zen Center in New York told me that he had “had an immediate and very powerful bond to Sasaki Roshi as my teacher. His silence and poise were majestic. And his ability to teach that the self – my ‘self’ – was not identical to my body was direct and powerful. I had never seen anything like that before. Of course I’d studied the teachings, but it’s different when you get it live than when you get it from a book. It has the power to break through your own mental states. And that’s why all this kafuffle is of no interest to me. I mean, he gave me such a profound gift that everything else is dwarfed.”

By “kafuffle” he meant the controversies around Sasaki’s treatment of women, which hadn’t improved after his move to the US.

Complaints surfaced early and were dismissed on the grounds that Sasaki was an enlightened Zen Master and anything he did with his students was actually teaching. One of the chroniclers of Sasaki’s exploits reported that when

– a young woman who was Sasaki’s assistant (inji) at the time complained about Sasaki’s constant sexual advances, one monk replied that “sexualizing is teaching for particular women.” The monk’s theory, widespread in Sasaki’s circle, was that such physicality could check a “woman’s overly strong ego.” Sasaki claimed his sexual advances were in fact teaching non-attachment and emptiness, core Zen values. [https://buddhism-controversy-blog.com/2017/07/16/ready-to-mine-zens-legitimating-mythology-and-cultish-behavior/#_ftnref16]

When male students did try to intervene on behalf of the women, Sasaki threatened to stop teaching if they questioned his methods. He also noted that having sex with young women helped him remain youthful.

Sasaki’s tendencies – although they were successfully concealed from the general public for a long while – became well known within Zen circles, and women who chose to study with him were often aware of the stories. Myokyo told me that she had been aware of the situation before she began her practice, and it hadn’t discouraged her from seeking to study with him. Even women who later complained about his behaviour often continued to admire him as a teacher. One of the women who wrote to the Witnessing Council established in response to the “Sasaki Affair” stated that she

– stayed with Roshi because my experience largely was that he was a great and gifted Zen and koan teacher, and I believe I received great benefit from the other sanzen meetings – those unburdened by his sexual interests. I had met with other Roshis and teachers, but I felt he was absolutely the deepest and best teacher.

As the number of incidents grew, even some of Sasaki’s most ardent supporters came to have doubts. In 1992, one of his senior students – Gentei Sandy Steward – disaffiliated his North Carolina Zen Center from Rinzai-ji specifically because “of my objection to the sexual behaviour and sexual teaching techniques of the Head Abbot” and “my disapproval of the lack of action by the Head Abbot, board of directors or ordained persons of Rinzai-ji to help those who have suffered on account of this behaviour.”

Things finally attracted attention outside the Zen community when in 2012 a former Rinzai-ji priest, Eshu Martin, published an open letter on the Sweeping Zen website which explicitly described the state of affairs in the community:

Joshu Sasaki Roshi, the founder and Abbot of Rinzai-ji is now 105 years old, and he has engaged in many forms of inappropriate sexual relationship with those who have come to him as students since his arrival here more than 50 years ago. His career of misconduct has run the gamut from frequent and repeated non-consensual groping of female students during interview, to sexually coercive after hours “tea” meetings, to affairs and sexual interference in the marriages and relationships of his students. Many individuals that have confronted Sasaki and Rinzai-ji about this behaviour have been alienated and eventually excommunicated, or have resigned in frustration when nothing changed; or worst of all, have simply fallen silent and capitulated. For decades, Joshu Roshi’s behaviour has been ignored, hushed up, downplayed, justified, and defended by the monks and students that remain loyal to him.

The letter spread through the internet, and its content was discussed on hard news sources like CNN and the New York Times. Seiju Mammoser spoke on behalf of the Rinzai-ji Osho Council in the New York Times article, admitting that he had been aware of the allegations against Sasaki since the 1980s and that there had “been efforts in the past to address this with him. Basically, they haven’t been able to go anywhere.” Seiju added:

What’s important and is overlooked is that, besides this aspect, Roshi was a commanding and inspiring figure using Buddhist practice to help thousands find more peace, clarity and happiness in their own lives. It seems to be the kind of thing that, you get the person as a whole, good and bad, just like you marry somebody and you get their strengths and wonderful qualities as well as their weaknesses.

In November 2012, Rinzai-ji cooperated with an Independent Witnessing Council made up of Zen leaders not associated with Sasaki or his centers. The council collected information from 25 individuals, half of whom experienced actual or attempted sexual contact with Sasaki. The findings were substantial and damning.

This was all a matter of public record when I met Seiju in 2013, regardless of which he remained loyal.

“A lot of people, in taking in all this stuff, have resolved it in their various ways,” Seiju told me. “What I found most difficult is that the propensity to get to a mind of judgment impedes understanding. Once I make a decision—‘That’s right; that’s wrong; this or that’—then I line up behind my judgment and act. I haven’t found a mind of judgment to be particularly helpful for a mind of practice. But the emotional urge to get to judgment, because there’s a lot of unpleasant stuff that has been talked about—and I can understand that—that would make people unsettled. But I’ve been on the inside for so long, I appreciate a great value that’s comes from studying with Sasaki Roshi. He’s a full-bore person. He completely does what he does. And in the human scope of things, everything becomes a thing. Things are entities. So Sasaki Roshi is a person. All right? You’re a person. That’s a dog. You know? This is a person. That kind of thinking. Very common. Very understandable. Very human. You know? That’s not what Buddhism teaches us. Everything is activity. Sometimes I manifest skilful activities; sometimes I manifest foolish activity. And sometimes I manifest selfish activity. I can be a loving parent, and I can be a terrible co-worker. And I can be both of those and all of those in the same day. And anything else. And in my experience around Sasaki Roshi, he’s been a remarkable, deeply committed teacher. Highly intense and highly demanding of his students. And also he can be very intense in these other areas. He’s completely consistent with his character, in terms of complete activity. And it seems that, at those times, we weren’t dealing with Joshu Sasaki Roshi; we were dealing with Joshu Sasaki, a Japanese man. And he could manifest both of those qualities. People presume that if you’re quote ‘enlightened’ end quote—whatever that means—or ‘awake’ or anything else, you can’t possibly do this other stuff. And I mean, I don’t know the answer to that. But it’s pretty obvious to me that the one person that I’ve spent time with who seems to come closest to what a lot of people would think of as an ‘awake’ person has also done these other things. And that, to me, is just skilful activity and unskillful activity. Which, again, we all do in our lives.”

Joshu Sasaki died on July 27, 2014, at the age of 107, without having named a successor. Rinzai-ji and Bodhi Manda and other centers associated with Sasaki continue to be maintained, according to the Bodhi Manda website, “by ordained Zen teachers (oshos), monks, nuns, and numerous lay practitioners.”

Myokyo was not surprised. “The tradition is that you must exceed your teacher in understanding in order to be named a successor. And I think for a lot of us, there was no one coming anywhere near that.”

When I began this series of interviews – when the news reports about Sasaki and others were casting a pall over the tradition – centre after centre I visited were struggling with the revelations and often reflecting on difficulties in their own pasts. These are issues I continue to discuss with those with whom I speak. The matter is often expressed in terms of the contrast between, on the one hand, the vows we chant – for example, to care for all beings without number – and the Precepts and, on the other, the behaviour at times of those who guide the community. Debra Seido Martin’s reflection stayed with me long after my conversation with her on this topic:

“Time to grow up, everybody. We can leave the naïve romantic chapter of Zen and become adults together. My teacher – Kyogen Carlson – was very humble about the expectations when I confronted him about the failings of [so many teachers]. As a woman new to practice, I was especially shocked when I first heard of male teachers’ sexual abuse of their female students. As an incredibly trusting new student, that I could be taken advantage of by someone in authority I trusted seemed awful. We have had much time to learn from this first generation and can now we can be adults. We can take responsibility for our own discernment and call out transgression when we see it. I wouldn’t say that teachers who transgressed had no respect for the Precepts, I think they were blind to their own shadow sides and left unchecked by an undeveloped institution around them. Kyogen said there were no guarantees as to the outcome of this practice for anyone. He was humble and said, ‘You know what? I’ve come to find out after thirty years of teaching, Zen inclines us towards wisdom, and it inclines toward compassion. That’s it. For everybody.”

2 thoughts on “Joshu Sasaki”