Empty Cloud Zen, California –

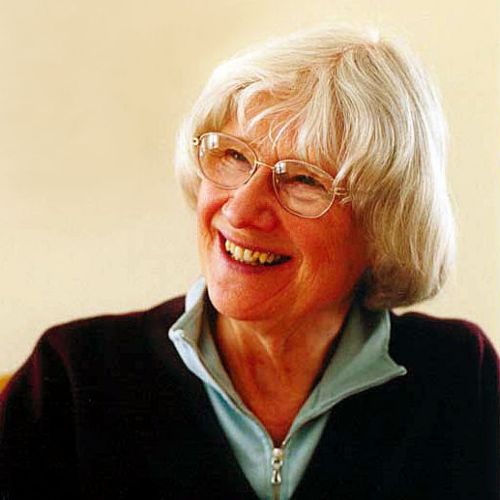

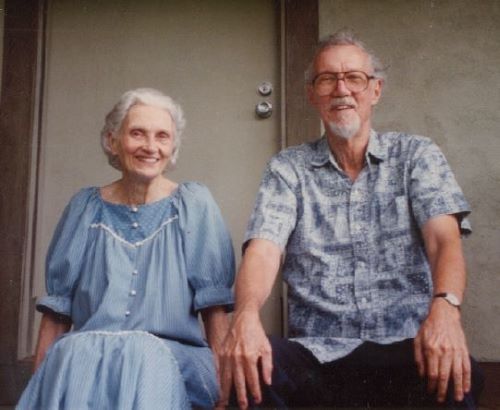

Nona Strong of the Empty Cloud Zen Sangha in Northern California grew up in Oklahoma City.

“Both my parents were from smaller towns in Oklahoma. And after World War II, they moved to Oklahoma City and bought a house. They were both educators – teachers – and they had me. I’m an only child. I have no sisters or brothers. Very few cousins. So, I grew up in Oklahoma City. Went all the way through high school there. And after high school, I went off to Washington, DC, to go to college at Howard University.”

I ask if her family belonged to a faith tradition.

“We attended the AME church – African Methodist Episcopal Church – there in Oklahoma City, but they weren’t real church goers. My maternal grandfather was a pastor of sorts. A pastor who read tarot cards for people. He was an eccentric. My paternal grandparents were devout AME church members. My aunt and grandmother were both members of the Eastern Star and all of this stuff.”

“Did it mean anything to you?”

“No. It was just what one did.”

“More cultural than spiritual?”

“More cultural. Exactly. They sent me to Sunday School where you learned ‘Jesus Loves Me This I Know’ and stories and so on that they teach kids. But my parents did not go to the church service that followed Sunday school. There was . . . I remember this! One Easter we went to church. My parents came and picked me up from Sunday School and said, ‘We’re staying for church today.’ And the pastor noticed them in the congregation and said, ‘Oh! We have Brother Paul and Sister Evelyn here today with their daughter!’ He called them out because they weren’t usually there. So that was, I’m sure, very embarrassing to them. Mortifying, in fact! It was a little embarrassing to me, too.”

She studied languages at Howard.

“I graduated in 1968 and went to work for IBM. IBM was recruiting very heavily on Black college campuses in those days in order to comply – probably – with the government rules. So I moved from DC to New Jersey and places farther west. In the ’70s I was living in Minneapolis and something welled up in me and dragged me kicking and screaming to this whole New Age mysticism movement that was flourishing in those days.”

I ask her how that came about.

“It just welled up inside from no place I could pinpoint even now. But there was a spiritual . . .” she pauses reflectively “. . . birth, you might call it, a spiritual resonance that began to sound within me to which I responded. And I responded by reading – if you can believe this – the novels of Taylor Caldwell. Great Lion of God about Peter and a bunch of other Christian figures. And that led to an interest in New Age spirituality, mysticism. I had the feeling there was something that I needed to connect with, and whatever path that led me on, I just had to follow that pull, that connection. So I started reading, Ouspenskii and Gurdjieff, Jane Roberts, all of those New Age thinkers and mystics, and eventually came to Thomas Merton. And Thomas Merton was the pivot for me to get into serious study and seriously consider what this whole mysticism thing was about, what it meant, and why I was there.”

Reading Merton, she decided she needed to be baptized. “I got baptized a Catholic. Because of Thomas Merton. Blame Thomas Merton for that. So I was a Catholic from Oklahoma. I mean, Oklahoma doesn’t do Catholics,” she says with a laugh. “I was living in Los Angeles at the time, but I had grown up in Oklahoma. So it was kind of a big step for me to do that, but it seemed necessary.”

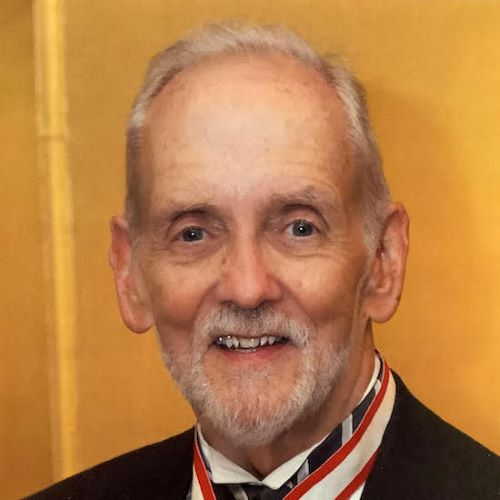

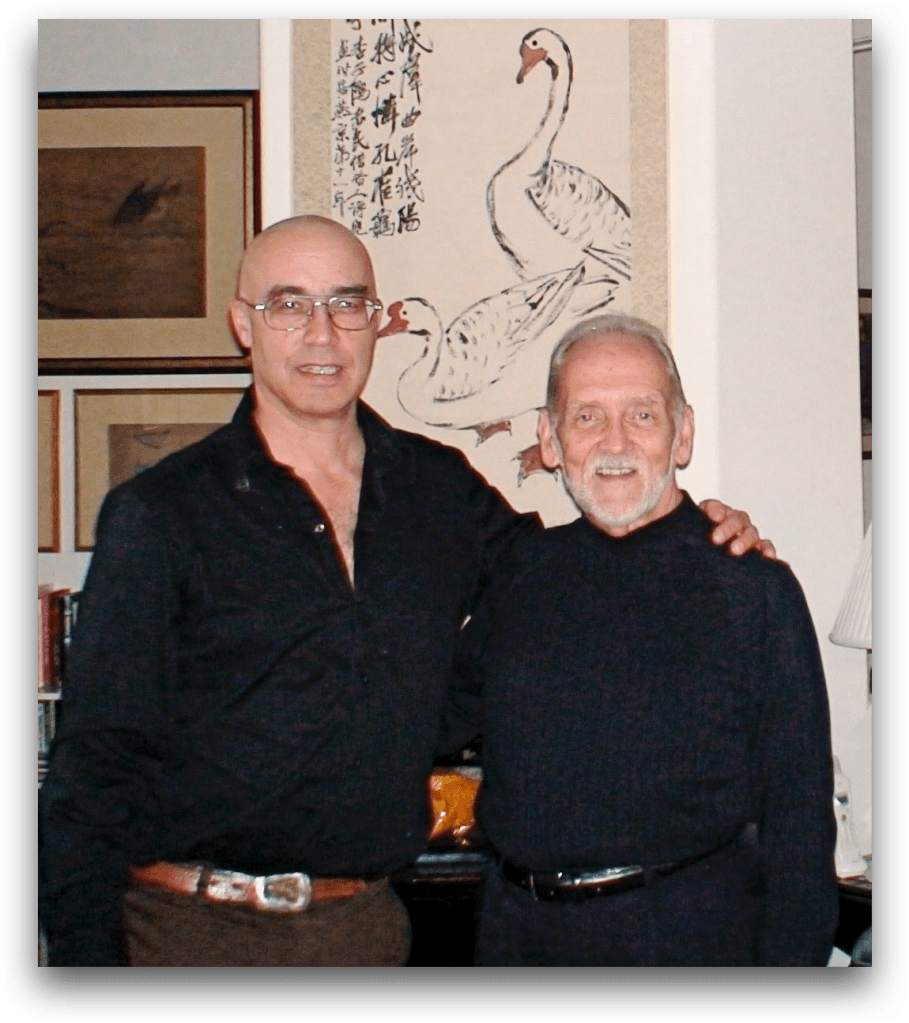

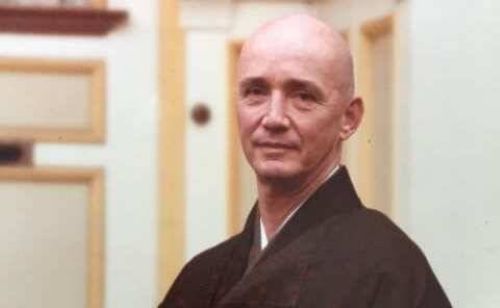

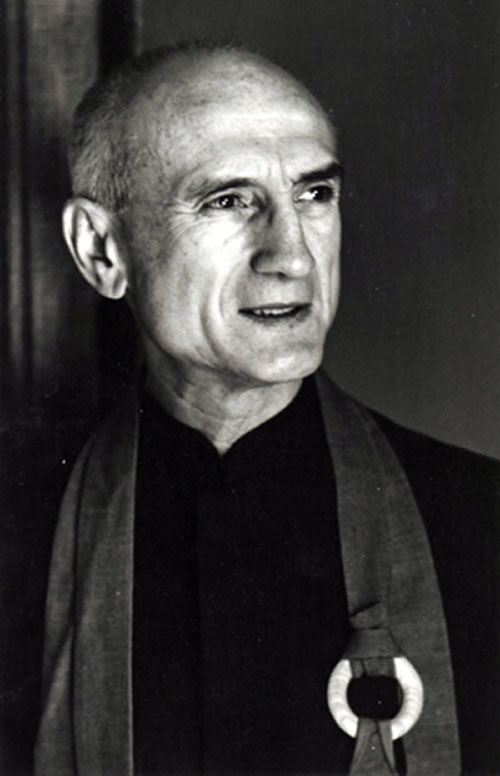

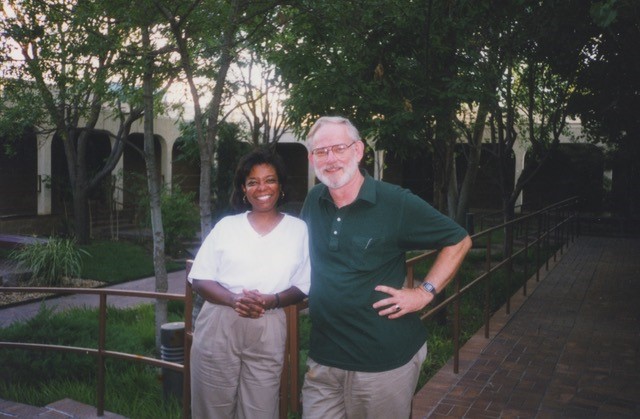

After the baptism, she went on a private retreat at the Mary and Joseph Retreat Center in nearby Palos Verdes, and there she met Father Greg Mayers, a Dharma heir of Willigis Jäger in the Sanbo Zen lineage. “I felt he was a mystic. So there was an immediate attraction there just because of the style and content of his teaching. And it was only later that I learned he was a Zen teacher. I didn’t know what Zen was at that time, but I knew what he was.”

At the time Greg was the director of the Bishop DeFalco Retreat Center in Amarillo, Texas, but he came regularly to the Mary and Joseph Center to lead retreats.

“So I started to attend these retreats. I’d never done meditation or anything like that. It was just part of this pull toward silent, mystical spirituality that I was undergoing. Like I said, I don’t know where it came from. It was just there.”

The point she returns to frequently during the conversation is that whatever was drawing her was not a matter of doctrine. “I recall telling someone, a friend, ‘I just need to find out who’s in here,’” pointing to her heart and head.

“And so after you met Father Greg, did you take up formal Zen practice?”

“Yes. I asked him if I could attend only his retreats because there was . . . You know, I think the transmission that I ultimately received from him actually occurred at the very beginning. Transmission sort of occurs when you first meet your teacher. ‘When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.’ So I said, ‘Can I just attend your retreats?’ And he said, ‘Yes. You can come to Amarillo.’ And I was self-employed by that time. So I had the freedom to do that.”

That was 1996. The next year she was in London, England, on business and decided “I needed to make a break with my life in Los Angeles and go ‘find myself.’” She elaborated on this in an email she sent me after the interview. “In early 1998, I gave away all my stuff, rented out my LA house, and struck out, by car, for a long stay at the Bishop DeFalco Center. I stayed there for ten weeks, during which time I sat by myself, made sesshin with Pat Hawk, and had dokusan with Greg. After Amarillo, I spent eight weeks alone at the Desert House of Prayer, a Redemptorist hermitage in Tucson, where I sat in meditation daily and gratefully took in the beauty and sacred quiet of the Sonoran Desert, along with a few other crazy hermits from around the US.”

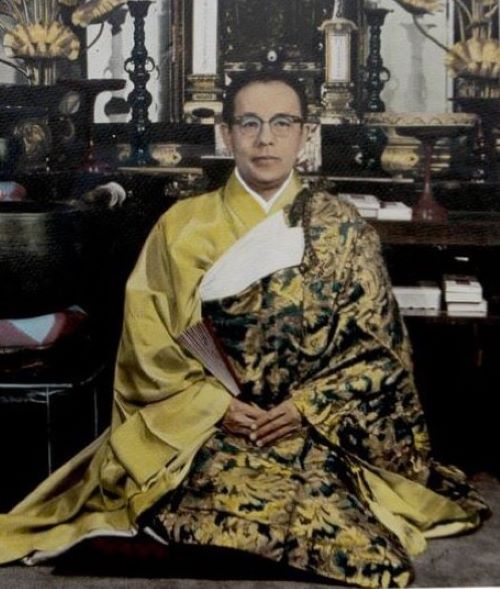

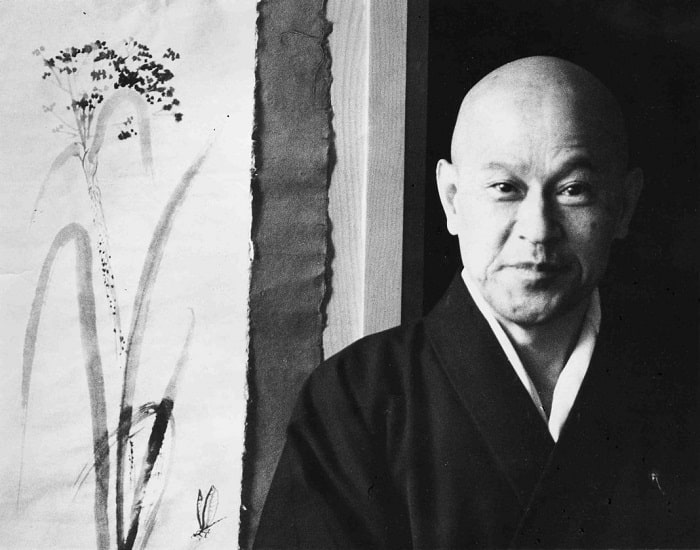

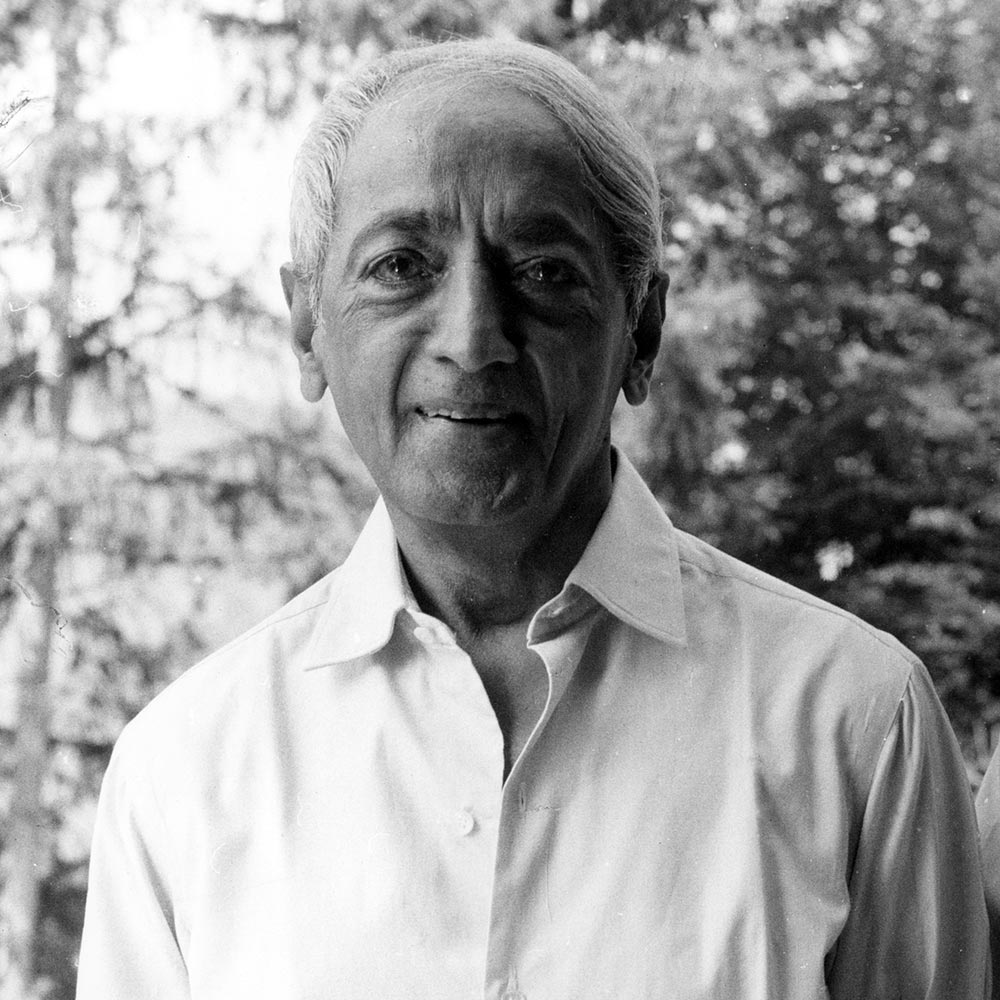

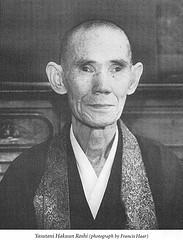

Greg encouraged her to go to Germany to study with his teacher, Willigis Jäger, a Benedictine Dharma heir of Koun Yamada. Nona describes the six weeks she spent with Jäger as a “most profound and enjoyable experience for me. Willigis was a remarkable man, a wonderful teacher, and a most gracious host.”

When she returned to the US, she moved to Sacramento to be closer to her father, and she continued travelling to Amarillo to attend sesshin with Greg Mayers.

“And somewhere along the line,” I say, “Father Greg decides that you’re going to do more than just practice. You’re going to take on a leadership role. How did that come about?”

“Lord! I couldn’t tell you,” she says, laughing. “I couldn’t tell you what was in his mind when he conferred that honor and obligation on me. Sometimes I see it as an honor, but sometimes I see it more as an obligation. First, I was one of his assistants. That’s kind of the way it came about. He had me ring the bell and do the readings and all that stuff from pretty early on. And then, probably in 2017, he asked me, ‘What would you think if I wanted to make you my Dharma successor?’ And it came out of nowhere. Now, I have a near-pathological level of self-doubt, and I said, ‘Are you out of your mind?’”

“You said that having transmission is not only an honor, it’s an obligation. What’s the obligation?”

“The obligation is to be there for other people. I’m a pretty solitary person by nature. Having been raised as an only child and having gone through life as a solitary person, it’s difficult for me to be called out of myself, out of my own space and have to – have to – devote myself or take my own time to attend to someone else’s needs. Although at one time I imagined myself as this kind of helpmeet for other people. There was a time when I considered being a psychologist, a psychotherapist. But that disappeared, that compulsion or interest dissipated when I looked at it practically and said, ‘But you won’t be able to go on vacation. People will need you, and you’ll have to be there.’ So the whole thing of being a teacher or a guide brought up that same reluctance of having to surrender my own privacy and my own solitude to the needs of other people. And, of course, there’s my sense of inadequacy and my self-doubt. I’m not that comfortable being out in front. But as it turns out, I’ve kind of been able to put my fears in my pocket and keep on stepping up, doing what’s been asked of me. That’s all I can really do.”

“What brings people to Zen practice?”

“Just based on the people I know who come for retreats, they come for several things. Some come because they think that there is some kind of peace of mind to be gained through Zen practice and meditation that they don’t get elsewhere.”

“So they come to it as a psychological practice.”

“Partly, maybe. But the peace they’re seeking is more about experiencing a sense of the sacred. Contemplating the mystery of life, I guess. People see meditation as a way to connect with something quiet, something sacred, something spiritual. I think we are all responding to the same pull that got me onto this path in the first place. Of course, people want to have a mastery of life. That’s the other thing that comes up. They want to be above all the bumps and pimples and stuff that they have in their lives now. They want peace within themselves. Some, probably most, want peace among others in society, and they figure that in finding inner peace, they’ll be able to spread that gospel of peace throughout society. Some may want to be enlightened. I mean, meditation practices are a lot more popular now than they were in our day.”

“So you’re saying that when people come to meditation now, they do so – at least in part – looking for a psychological technique. How does it become a spiritual practice?”

“Well, some people have gone through mindfulness training as they do in the corporate world now. Some people are Christians. The Mercy Center and Father Greg have this East-West dimension, him being a priest and having embraced Eastern wisdom. And I think a growing number of people sense that there is something within their Christian tradition that leads to a more inner-directed practice. I think more people are looking for something that’s more inner-directed because the outer is so messed up now, and people are looking for a way to immerse themselves in a space that’s beneath the turmoil. Or above the turmoil. Or outside of the turmoil. But not wrapped up in the turmoil, not tossed and battered. And people are looking for a way not to be tossed and battered, I think. And so much of what is happening now and has been happening over the past umpteen years is a tossing and battering of ourselves, of our wishes and desires, or our need to escape our wishes and desires.”

“So I suppose if I were a Buddhist, I’d call that dukkha.”

“Dukkha. Suffering. Yeah. Yeah. Some people have started referring to suffering as angst or anguish, rather than suffering. When I hear ‘suffering,’ I think of someone in terrible pain. You know? Or someone suffering through a divorce or the loss of a child.”

“Albert Low pointed out that the etymology of dukkha is that it basically means out of alignment. He would use the example of a grocery-cart where one of those wheels just isn’t rolling smoothly. That’s dukkha. It isn’t just big things like the death of a child; it’s all those little petty grievances like that grocery-cart wheel.”

“Yeah. Yeah.”

“So,” I ask, “when people come to get relief from all those petting little things, what is it that they look to you for?”

“I don’t know. I have a group that meets – fifteen or twenty people – every Thursday. And they come to sit in silence, but I also give a Dharma talk each week. So I don’t know if they come to hear the talk or they come to sit. I always worry that I’m not giving them enough when I give the Dharma talk. But then I think, ‘Well, maybe they just come to sit, and – you know – the Dharma talk is an interruption in their sitting.’” She laughs heartily. “I don’t know why they come.”

“But they show up.”

“But they show up. They’re there.”

“And they come back.”

“They’re there every week.”

“So they’re finding some kind of nourishment. What is it that you hope for them?”

“I hope that they can find within themselves a deeper and more solid connection to what is, to . . . I don’t know – call it cosmic reality if you want – than when they came in. A deeper . . . Not more committed, but a broader understanding of who they are and where they fit in the whole universal paradigm.”

“The word you’re not using here is ‘God.’”

“No. It’s not about God. I don’t even know what God is. I have a kind of a resistance to the use of that word because I think it tends to personify what’s real in a way that can be detrimental to a person’s experience of being. ‘God’ is such a loaded word, loaded notion, a loaded concept.”

“Tell me about koans.” She doesn’t immediately respond. “That friend you talked about earlier, the one you told that you ‘need to find out who’s in here,’ if they’d asked what koans were all about, what would you have told them?”

“At the time? I would have said they were scenarios that allowed us to penetrate through life situations and find the truth – quote/unquote ‘truth’ – that lives in those life situations. They’re, of course, supposed to produce kensho – the explosion, the fireworks – that brings you from lower case life to Upper Case Life, if you know what I mean. In other ways, they’re just little obscure stories designed to confound you – to completely confound us – and to exhaust our thinking minds.”

“That’s what you would have said at the time? What about now?”

She reflects a moment, then says, “I’d go for the penetrating purpose. I want people who are working with me to be able to read these stories and through them get a glimpse of what has been, is now, and ever shall be. Going back to my doxology from Sunday School. I mean it’s that which endures. That which is. That which is out of time. And these little stories are supposed to be – or can be, at least – a trigger for us to be able to see through the life situations down to the uber-life situation or the under-life situation or however you want to phrase it. That’s what I would say now.”

“You said koan study was supposed to ‘of course’ (your term) produce kensho. Did it?”

“No. For me, my ‘enlightenment,’ or ‘awakening,’ experiences all came from or came through or came as that same pull that got me on this path in the first place. Koans can get in the way for me because they almost point to doctrine, and that’s a little scary for me to say. But they want to point you in a certain direction. But what’s at the end of that direction is already within you.

“Are you suggesting they point you to an experience of what the doctrine is an expression of?”

“The experience of what the doctrine is an expression of. Exactly. Thank you for that phrasing.”

As the conversation winds down, she says she’d like to speak about “the subject of how that whole pull toward mysticism and mystical spirituality has crept into my Zen practice and my Zen teaching or guidance or whatever. And I’m kind of in the middle – right now – of an Experience. And if you write that down, please write it with a capital E. It’s like one of those things that happen, another pull that’s happening in which I am drawn to emphasize or to – yeah, ‘emphasize’ is the only word I can think of – emphasize the mystical element in Zen practice, Buddhist practice. I’m more settled in the mystical aspect of spirituality than I am in the doctrinal. And there is Zen doctrine. I mean, koans are part of it. There’s Buddhist doctrine; the Precepts are part of it. I feel like I’m distancing myself from all of that and going more to what those traditions represent, what they’re trying to express. And what they’re trying to express lies beneath the traditions themselves, the doctrines themselves.”

“Traditionally I would understand ‘mystical’ to refer to the experiential rather than the reasoned or rational understanding. Is that the way you’re using the term?”

“Yes. Precisely.”

“So going back to that sense that the work of koans is to assist one in experiencing directly that which the doctrine is an expression of.”

“Yes.”

“And when you work with students in this way, how do you help them achieve that experiential understanding?”

“I let them sit with the koan and then encourage them to express what that koan has awakened in them. What the story has awakened, what the story is pointing them to. It’s not just about understanding the story. It’s standing with the story.”