A conversation with Ruben Habito

The Sanbo Kyodan school was founded by Yasutani Hakuun in 1954 when he formally cut ties with the Soto Establishment in Japan and promoted a style of Zen based on the work of his teacher, Harada Daiun. The suffix “-un” in both given names means “cloud” and would become common in the Dharma names used in the lineage. The name of the school refers to the Three Treasures of Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma, Sangha.

Harada had entered a Soto monastery at the age of 7 but came to feel the Soto system of training was insufficient and, as a consequence, took up Rinzai training at Shogen-ji in Shizuoka. There he undertook koan practice, which had been discontinued in Soto circles in the 18th century, and achieved a kensho (awakening) experience. Although he went onto become abbot of several Soto temples, contrary to Soto custom he advocated koan practice and worked with lay students.

Yasutani – one of Harada’s fourteen successors – also worked with lay students and had several Western students, notably Philip Kapleau, who would be instrumental in the process of adapting Zen to the West. Yasutani’s immediate successor as Abbot of the Sanbo Kyodan school was Yamada Koun, who may be credited in large part with the substantial success the school achieved internationally during the Zen boom of the 1960s and ’70s.

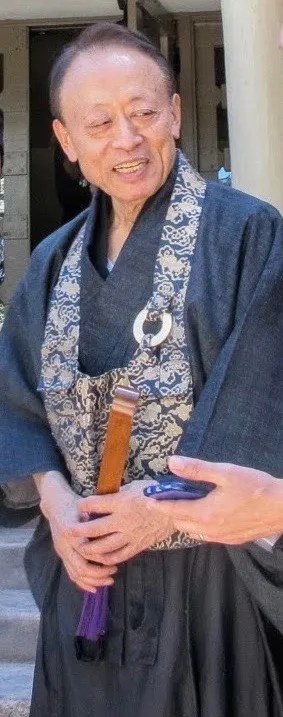

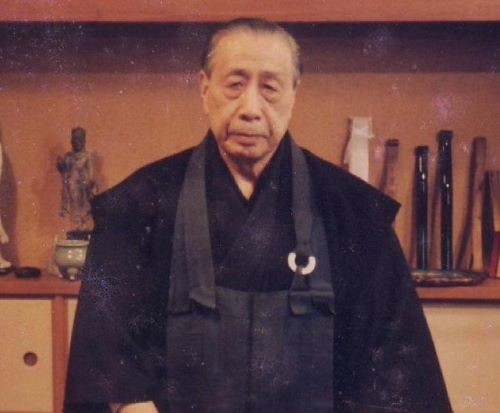

Ruben Habito was a Filipino Jesuit seminarian in Japan when he met Yamada and would go on to become one of his several Western Dharma heirs. His Dharma name is Kei’un-ken, “Grace Cloud.”

“I first met Yamada Koun Roshi in the fall of 1971. I had arrived in Japan the year before to start my language classes to prepare for further education and then ministry in the Catholic Church with the Jesuits in Japan. The first thing we were assigned to do is to learn the language for two years. So I was living in Kamakura where the Jesuit language school was located. And there was a Japanese student at Tokyo University who had asked me to coach him in English and in exchange he was coaching me in Japanese. And this student comes to our lesson one day and said there was a special Zen retreat for students at Engakuji, this Rinzai temple just one railway station from Kamakura where I was. He said for the equivalent of $10 in US – 1000 ¥ – you could get two nights lodging and food for all the meals that you would need and guidance in Zen. So, I felt, ‘Hmm.’ I had heard about Zen from D. T. Suzuki’s books and so on. I had also been told that to be able to understand Japanese culture, it might be helpful to learn about Zen from a theoretical angle. My then spiritual director at the language school, Father Thomas Hand, was already practicing Zen with Yamada Koun.

“It was a three-day retreat beginning Friday afternoon and ending Sunday noon in a big temple which has a hall that can take more than a hundred sitters at the same time. It was Rinzai so it was on elevated platforms called tans. And those tans were also our living space. That was where we slept. It was the rough Rinzai style. We would be awakened at 3:00 in the morning, and then by 3:20, just twenty minutes rushing to the common washrooms and so on, getting washed up, and then we have to be back on our tan by 3:20, already seated facing one another. And there were easily a hundred or 120 students, male and female. Anyway, I came out of that with aching muscles and aching bones and so on, but with some kind of sense that there was something exhilarating in what I experienced. And so I felt I should have some more of that.

“So I went back to the language school, and Father Hand asked me, ‘Would you like to come with me to the zendo, the San’un Zendo, and meet Yamada Roshi?’ And I said, ‘Sure. Of course.’ So I went for orientation. First you have to listen to talks. There were six introductory talks that were given on certain days before the formal introduction to the roshi. So I took those, and after that I was formally introduced to Yamada Roshi in a one-on-one dokusan. And that was my first meeting with him formally. I had, of course, seen him seated among the other sitters, and he would be there and giving talks and so on. But my first one-on-one, person-to-person contact with him was in that dokusan context.”

“How old was he when you met him?” I ask.

“That was in 1971, and he was born – I believe – 1907, so he must have been 63 or 64.”

“Do you remember your initial impression of him?”

“I was awed, frankly. He had a sense of gravitas. And yet at the same time, he had this kindly heart that took you in, and you felt that you had a place in his heart. He didn’t show it in a kind of an oozing way that you might imagine. He was very formal, but you know that he was there, and that he was holding you in his heart and listening to you. That was what really struck me then. So I was totally free in opening my own heart to him.”

The San’un Zendo where Thomas Hand brought Ruben was very different from the elaborate Engakuji temple. Although Yamada Koun was an authorized Zen teacher, he was not – nor had ever been – a monk. He was a lay practitioner and Chairman of the Board of Directors of Kenbikyoin, a large Tokyo clinic in Tokyo, where his wife, Dr. Yamada Kazue, was medical director. He continued in this role until his death, teaching Zen on evenings and weekends, as well as presiding over frequent weeklong sesshin. When Yasutani Hakuun retired in 1969, the Yamadas built the San’un Zendo in their family compound. It was neither a temple nor a monastery, but a small center where lay persons could practice. It would be a model of the type of center which would become common in North America. The name “San’un” meant “Three Clouds” and referred to the first three masters in the lineage, Harada Daiun (Great Cloud), Yasutani Hakuun (White Cloud), and Yamada Koun (Cultivating Cloud). The Center attracted not only Japanese practitioners but Western students as well, including several Catholic priests, seminarians, and Sisters.

Like Yasutani and Harada before him, Yamada had a sense that Zen was floundering in Japan.

“He could be critical,” Ruben tells me, “saying that, ‘Zen in Japan has now become a funeral service. The priests are not really sitting seriously anymore, and they don’t offer opportunities for really going deep into the practice. They have their livelihood; they have to go and visit the families within their area, those that are registered in a temple. So they have become temple functionaries.’ He was known to have made that critique of Zen in Japan, so that’s why he said that ‘We need to revitalize Zen.’ And he saw that the Western students were very zealous and engaged in it, so he saw that maybe there was something there that could really revitalize Zen, and he encouraged us to do so.”

The first Canadian to be authorized to teach Zen was a Roman Catholic nun from my province of New Brunswick, Elaine Macinnes. She told me that Yamada had even expressed hope that Zen as a tradition might find a home within the Catholic church.

Ruben tells me he had heard the same thing. “He had that idea. And this is what he told us at some point; maybe on more than one occasion when there were a good number of us from other countries whom he knew were Christians. So he said, ‘My advice to you is really, go deep into the heart of Zen, that Zen which is beyond words and beyond concepts and really soak yourself in that. Before you think of teaching or anything you can do to help others, first soak yourself in that Zen experience and let it be what sheds light on your own life. And then from there, learn the language to be able to offer pointers and guidelines to people who are within your religious context. So learn your Christian scripture; so learn your theological vocabulary. And let that language and conceptual context be what you offer so that they can go to that place that is beyond words and language, words and concepts.’ So that’s how he encouraged us. And he also told us, ‘I’m a Buddhist, so I can only talk to you and give you guidelines from my Buddhist terminology and from my Buddhist background.’ So he was encouraging Christians to look into the heart of Zen and then use their Christian vocabulary so Zen students can really find a home within their religious organization.”

After Yasutani’s death in 1973, Yamada became the second “abbot” in the Sanbo Kyodan School, although Ruben suggests the term is problematic, because it is derived from Western monasticism. “‘Abbot’ is really an anglicization. The word in Japanese is kancho. ‘Kan’ means ‘institution,’ and ‘cho’ means ‘head.’ So, ‘Head of the Institution.’ And so just an English way of saying that it’s a religious institution, and so it is like an abbot in a monastery, so they just borrowed that term.”

I ask Ruben what qualities, in his opinion, Yamada had which permitted him to work with North Americans and Europeans so successfully.

“Well, he could somehow understand English, and he could utter a few sentences. But he would always be helped by a translator, of course. When he noticed there were more and more non-Japanese coming to his Zen group, he asked one of those who were bilingual to translate his teishos. So he gave recognition to these non-Japanese practitioners, and he welcomed them. That’s one thing. Another thing is Yasutani Hakuun was known for his very rigid Buddhist understanding of Zen, that Zen is Buddhist and he would tell people who came from other religious positions, ‘You have to check your religion at the door before you enter the Zen hall.’ Especially this sense of God, he said. That’s a distraction, and you have to get rid of that before you can really go into real Zen. That was Yasutani. For Yamada, however, he noticed that those who were coming to him from other countries were not just lay Christians but also priests, nuns, Protestant clergy, and so on. And he didn’t say anything to them. He just welcomed them and gave them basic instruction in Zen and led them in koans. And he noticed that they were also able to come to a deep experiential realization. So in the beginning he would say, ‘If you’re a Christian if you come to Zen you can become a better Christian. If you’re a Buddhist, of course, you will realize what it means to be fully Buddhist when you see your true self as a Buddha. But for Christians, you can be a better Christian.’

“So, that was his way of saying it. He did not say check your Christianity at the door. But you can be a better self. Because he noticed that Christians were also coming to practice and even breaking through and being able to practice with the koans in a way that was not different from the way Buddhists would go through the koans. There you don’t talk about theological concepts at all, but it’s a practical approach of just seeking the here-and-now in the context of the timeless infinite. And so he could see that those who remained Christian could still have that same depth.”

Ruben believes this openness to other cultures was also a factor in the success the Sanbo School achieved outside of Japan.

“It was the open-hearted way of inviting people of any background and cultural or conceptual framework or religious conviction to be able to simply sit, be aware, and go deep into that stillness. So the basic instructions for going into that place beyond words and concepts is the same across traditions. You don’t need to go into theological language to be able to taste what Zen offers. It is this adaptability to different conceptual frameworks that people have. That people are not asked to give up their religion or conceptual framework or understanding of reality before they enter into Zen. They just are invited to sit still based on the instructions that are given, breathe with awareness, and go deep into that stillness. And then the emphasis of Sanbo Zen is that it is an experiential journey. You don’t have to believe in anything as a kind of a faith commitment to be able to practice. It’s an invitation to an experience. So you can be Buddhist, you can be Christian, you can be Muslim, you can be atheist. But the practice is inviting you. So it is precisely that kind of broad appeal to people across different religious traditions that may be one of those attractions that Sanbo Zen has.”

“So,” I suggest, “rather than being a philosophical point of view – which Buddhism is – it is a practice that goes beyond the Buddhist framework and is accessible by people who adhere to other traditions. Is that what you’re saying?”

“Yes. It is a set of guidelines for practice and experience that is accessible to people beyond the Buddhist pale or beyond the Buddhist circle. Now it may be cached or it may be expressed in Buddhist terms, but technically one doesn’t have to be Buddhist to be able to practice Zen. That would be one way you could say it, and, in fact, there are some of the early teachers like Willigis Jäger[1] and Ana María Schlüter[2] who would say, ‘I’m not Buddhist, but I practice Zen to the full.’ Now, I’m not able to say that because I’ve also learned enough from the Buddhist tradition that I feel that I cannot disclaim it from my identities. So what people say of me is that I am both Buddhist and Catholic at the same time.”

After his death, Yamada was succeeded as Kancho by Kubota Jiun (Compassionate Cloud). Yamada and Kubota had both assisted Philip Kapleau in gathering the material included in The Three Pillars of Zen, and it is still a matter of irritation for some within the Sanbo lineage that they didn’t receive title page acknowledgement for their contributions. The fourth, and current, Kancho of the school is Yamada Koun’s son, Masamichi (Ryoun).

In 2014, the school’s name was changed because the term “Kyodan” had been associated with a terrorist group known as Aum Shinrikyo Kyodan, the Religious Community of the Truth of Aum. “And so,” Ruben explains, “because the last two terms – Kyo-dan – were the same, the leaders of our group said, ‘Let’s drop that name and just call it Sanbo Zen International. Sanbo Zen in Japan, and for those who were now operating abroad, Sanbo Zen International.’”

I note that the reference to the “Three Treasures” was retained and ask how that term is understood by non-Buddhists in the school.

“The Buddha is the awakened one, and you can be awakened. So you have that nature of being awakened; so you are Buddha. The Dharma is the truth that liberates. And Sangha is the community that supports you in your practice.”

“And it does not necessarily have to be a professed Buddhist community?” I ask.

“Correct. It does not have to be specifically Buddhist. But the Awakened One, the teaching toward awakening, and the community that supports living an awakened life would be Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Now you can interpret it in a Buddhist way, but even that kind of makes it more generic in terms of the intent of those three words.”

As our conversation draws to an end, I ask Ruben how he hopes Yamada Koun will be remembered.

“He opened Zen to people of different backgrounds and religious commitments that made it possible for them to consider it a path that they can fully take on.”

“Making Zen accessible to a wider swathe of people?”

“Correct. Without compromising their own religious commitment. Of course, as they do so, then they themselves see the transformation they need. They can’t hold onto this or that concept any longer. They begin to have a new understanding of those concepts. A new understanding of God, for example, a new understanding of the Trinity. For a Zen practitioner it becomes a much more personal, experiential way of living one’s religious life rather than just believing in this concept and so on. So it’s a way of enabling somebody with a specific religious set of commitments to re-understand those from a more experiential point of view. Not just take it as a doctrinal statement that they have to subscribe to.”

[1] A German Benedictine monk and Zen teacher.

[2] A Spanish professor of Ecumenical Theology.

6 thoughts on “Koun Yamada and Sanbo Zen”