A conversation with Peg Syverson –

Joko Beck died in 2011, before I began doing these interviews. I never met her but have spoken with several people who knew her. Peg Syverson was one of the most informative of these.

Joko was the founder of the Ordinary Mind School of Zen and became one of the most influential Zen teachers to arise after the first generation of teachers had established the practice in North America, and yet she didn’t take up the practice until late in life.

“I think she was in her late 40s,” Peg tells me. Peg is one of the senior teachers with the Appamada Zen Sangha and was first authorized to teach by Joko. “She had been married in Michigan to a professor who developed schizophrenia – they had four children – he had to be institutionalized. She moved to California and ended up being the administrator for the Chemistry Department at UC San Diego. She was a brilliant administrator for a department with a lot of very renowned chemists. She said, ‘They would wait until my boss was outside the room, and then they would come and ask me questions.’ Even before she had any Buddhist practice she was already kind of a resource for people.

“What she told me was that she went to a talk by a roshi – I don’t remember who, it might have been Soen Nakagawa – that she was completely struck by, and so she began to find out more. She signed up for a sesshin with Soen Roshi, and she told me she went in to have dokusan with him and told him she was ready for enlightenment. So he put her to work in the kitchen. For that entire intensive, she only worked in the kitchen. She never got out! She was cleaning every square inch of it. They took shelves apart. They cleaned things with toothpicks. She was cleaning, cleaning, cleaning all day. She never even got to sit in the zendo. But, she said, something shifted in her; it moved something in her. She has a talk about this. I don’t know if you have access to any of the recordings of her talks, but they give a great sense of her personality. She was tart and funny and pragmatic, a very witty and mischievous kind of person sometimes. After that, she started a regular practice, going back and forth to the Zen Center of Los Angeles from San Diego.”

“Did she choose ZCLA because of its proximity to San Diego?”

“Soen Roshi was going back to Japan, and he told her to work with Maezumi Roshi. And she said, ‘I was so naïve, I just thought a roshi was a roshi.’ So she was going back and forth to LA. Her daughter, Brenda, had a huge opening when she was fourteen. I’m not sure about the timelines of all this because Joko gave me these stories in pieces. But she got involved with ZCLA and ultimately took early retirement from the university – they gave her some kind of golden parachute – and she went into residence up there.

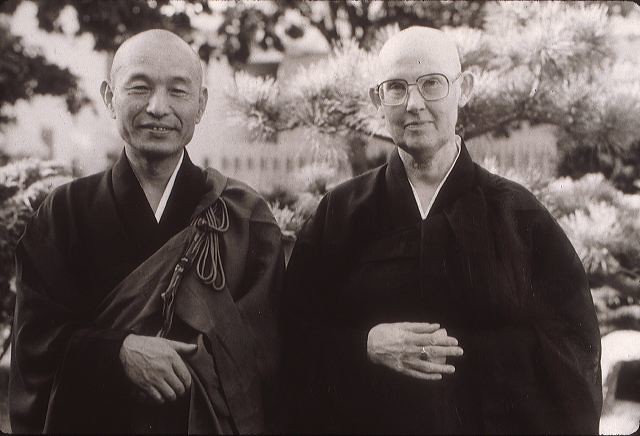

In 1978, Joko became the third person – after Bernie Glassman and Genpo Merzel – to whom Maezumi gave Dharma transmission.

“She told me, laughing, that, ‘He had to give me transmission because people were waiting in lines outside my cabin.’ And he kept asking them, ‘What is she doing in there?’ So he gave her Dharma transmission, but she told me it split the sangha, I believe it was A) because she was a woman, and B) because she was an American.”

“Maezumi had at least four female American heirs, didn’t he? Chozen, Joko, Susan Andersen, and I’m pretty sure there’s another.”[1]

“Yeah, after Joko. So he had transmitted Chozen, and that was famously controversial.”

“Because of their affair. But Joko’s transmission was controversial because she was a woman and an American?”

“I think that was maybe because up to that point Dharma transmission was not yet well established here. Transmitted teachers came from Japan, but they had been transmitted in Japan. So it was one thing when they started ordaining priests in America; it was another thing when they started giving Dharma transmission.”

In 1983, Joko went to San Diego with the intention of founding a center there.

“Her daughter, Brenda, was with her.” Maezumi had said that Brenda was the foremost expert on Soto ritual in North America. “Then Brenda went to medical school, and when she came back to visit, she said, ‘Mom, mom, mom, this isn’t working at all. These people aren’t trained; they don’t know what they are doing.’”

“She meant Joko’s students in San Diego?”

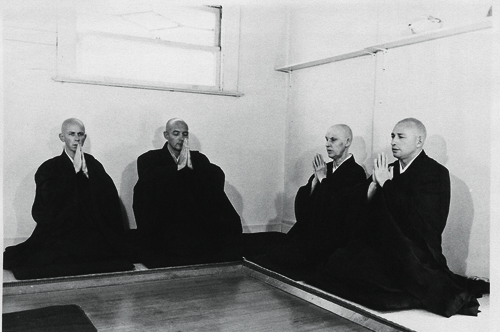

“Yes. Brenda said, ‘They’re fumbling around. They need to be trained in the roles, or you have to strip down to just what is essential.’ Joko told me, ‘Everybody thinks I’m opposed to the forms. I’m not opposed to the forms. When they are properly done, they’re beautiful. But,’ she said, ‘we couldn’t carry them out properly with a householder sangha coming and going, coming and going.’ It’s not like when you have priests or residents. When you have residents, they learn the roles. ‘So,’ she said, ‘I did what Brenda suggested. I pared it down to just what essential.’

“What I learned at her center was a very spare form of Zen, where there were three bells to start zazen, two bells to end it if there was going to be kinhin, a little talk, not much chanting. I never saw a ceremony the whole time I was there. Not a single ceremony. It was very simple. Very basic, but very deep. I’ve learned since then that there are different models of sangha. There’s the monastic model; there’s the residential model with householders who come and go; there’s a straight-up householder sangha. And they each have their own set of challenges to deal with. One of the challenges for Joko, I think, was she was not sangha-minded. She was individual-minded. So she had individual practice discussion, individual daisan with students, but there wasn’t anything organized – other than sesshins – that brought people together in an intimate way or connected them with each other. Yes, friendships formed, and people would go off to lunch together; they’d recognize one another from being in multiple sesshins or everyday practice, and there was a board that worked together. There were some people who were regulars, but there wasn’t a sense of a bonded sangha, in my view anyway, maybe because people were travelling pretty far distances. You know, even in San Diego, you get on the expressway for forty-five minutes to get anywhere. So when Saturday morning program would end, everybody would just go home. Usually a couple of people would go out to lunch together. Maybe, with my limited schedule, I just wasn’t aware of deeper bonds of sangha among members.

“Still, everybody was devoted to Joko, and I call this the hub-and-spoke model, where everyone has a relationship with the teacher but not so many relationships with each other. But I think it was a very beautiful environment to be learning in in a certain kind of way, because it was very peaceful, and from what I saw, there wasn’t a lot of drama. At least until the end. There wasn’t gossip and backbiting and that kind of thing going on. It was just very peaceful. It was exactly what I needed. My marriage had blown up; I was in graduate school fulltime; I was working three jobs; I was a single parent. So I really, really needed that peaceful environment for at least an hour or two a week. I could only go to Wednesday evenings, and, occasionally, friends would look after my son, and I could go to sesshin. Yet Joko and I formed a really strong, deep bond right away, from the moment I met her. And I think she always appreciated what we were doing at Appamada.”

“What do you think was the basis of that bond?”

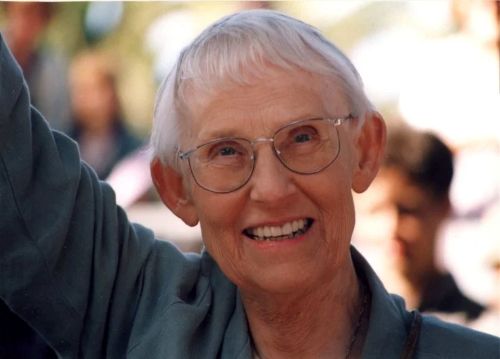

“Well, she had been a single parent struggling to make ends meet with four kids, and she had found her way to a devout practice, and that was where I was headed. So . . . I don’t know. When I first met her, it was like putting my bare hands on an electric fence. I couldn’t understand why the other people in the room, their hair wasn’t standing on end. It was like a bolt of lightning right into me. So it’s one of those kinds of experiences I’ve never had with another person until I met Flint, of course.” (Flint Sparks is her teaching partner at Appamada.) “It was more like a recognition than anything else.”

“You said Maezumi had to give her transmission because people were already treating her like a teacher. Why? What drew people to her?”

“I think it’s almost impossible to describe those qualities. She had a deep, deep, profound love of her students. But she was not sentimental. You wouldn’t say she was tender-hearted. She was more like the Sword of Manjusri, but there was so much clarity in it and so much care in it that you could tell she was seeing something you were not able to see about your own life that sort of righted things somehow. She had such immense clarity it was quite astonishing. And watching her working with people when they asked questions was always so profound. Like one of these young guys after a sesshin during the questions-and-answers asked her, ‘Are you enlightened?’ She immediately said, ‘I hope I should never have such a thought.’ I mean, just imagine that lightning response. It was just like people were drawn to her unique perspective, I think, and her depth of understanding. One of her German students, Claudia Willke, did a documentary of her life,[2] and it gives you such a sense of her personality. It’s so clear. She says in it, ‘Zen is not therapy. But I have students who need therapy. They really need a therapeutic response. And so,’ she said, ‘for those students I take a therapeutic approach.’ I think she felt that the psychological element had been lacking in her training and in her experience with the traditional center.”

“It was generally lacking in Japanese Zen,” I note.

“Yes, or any other understanding of the significance of emotions in practice. Not just having emotions, but the powerful effect of our emotional response to practice. She was very understanding about that. She was very interested in psychological perspectives.”

“You said, ‘There wasn’t much drama until the end.’”

The drama had to do with two of Joko’s transmitted heirs who felt that she was showing signs of dementia. As a result, the board met and changed the by-laws so that the center was no longer established to foster Joko’s teaching, and her role was now that of an employee of the center. Eventually Joko left San Diego, severed her ties with the center, and rescinded the Dharma transmission she had given the two perpetrators. She moved to Prescott, Arizona, with her daughter, where she began a new center. Peg and Flint visited her there, and Peg asked Flint – who was a psychotherapist – if he say any sign of mental deterioration in Joko. He said he didn’t, and that she was “as sharp as a tack.”

Toward the end of Joko’s life, Peg received a call from “one of Joko’s senior students, Barb, who told me, ‘Joko wants to start a new school that’s headed by you and Flint and me.’ Joko at that point was too old to really head up that new endeavor. Still, I was so touched by that, because I thought she really . . . You know, all I ever wanted in my practice was that bond with her. Just that sense that she saw me and that she approved of what I was doing. When I would take her pictures of Appamada, she was so pleased. Towards the end, when Flint and I visited her in Prescott, we knew it was probably for the last time; I was weeping in daisan, and the last thing she said to me, with such love in her eyes, was ‘Look what’s become of you.’ She was so proud. Her approval meant so much to me. It touched me so much.”

“What’s the most important thing I should know about her?”

“Her deep, deep love for her students, that deep, abiding love for her students. I think her book, Everyday Zen, was a reason people outside the sangha came to know of her. One of her students had edited her talks and put it together. It was a real labor of love. And for a while it was the best-selling book on Zen in English. It had a broad reach. It was so approachable. It was so down-to-earth. People could really relate to it, and I think that was a big part of its success. So those were the pair, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and Everyday Zen that we always gave people who were new. It was a great combination. A great American woman teacher with her practical down-to-earth approach and the beloved traditional Japanese Zen master Suzuki Roshi. A good combo.”

[1] Nicolee Jikyo McMahon

🤶❄️☃️

LikeLiked by 1 person