Appamada – Austin, Texas

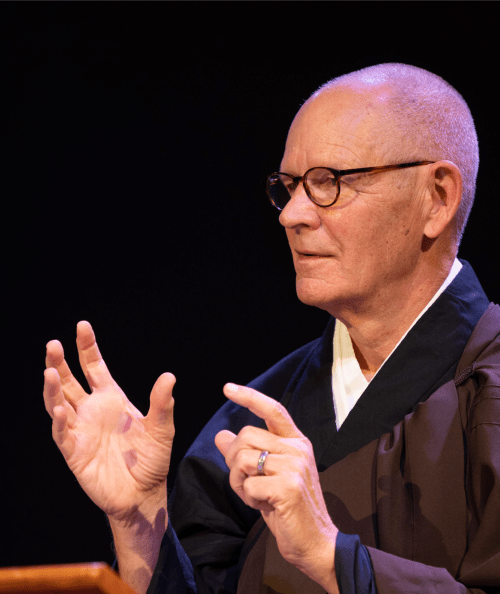

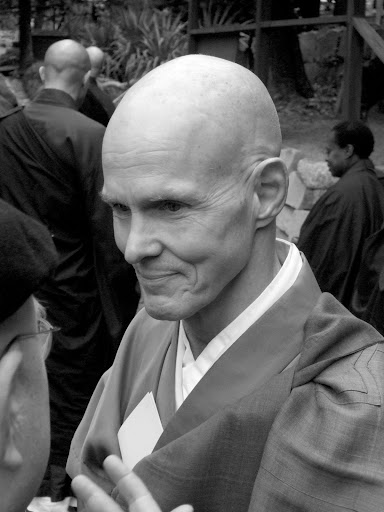

I begin my conversation with Flint Sparks by asking if that was, indeed, his birthname or perhaps a nickname

“It’s my real name,” he tells me. “I grew up in Texas as my dad did, and he was a real fan of the cowboy novel genre. There was one series he was reading as a young man – Flint Spears, Rodeo Cowboy Contestant – about this character he admired. He read it in 1941. I was born ten years later, but as he read it, he thought, ‘If I ever have a son, I’m going to name him Flint.’ So when I was born, he suggested that I be named Flint, but my maternal grandmother said, ‘You can’t name him that. People are going to make fun of him. Flint Sparks is a full sentence.’ So my first name is actually Thomas and my middle name is Flint. But who’s going to call you ‘Tom’ when you have a name like Flint Sparks?”

I ask what growing up in Texas was like.

“Well, as you might imagine, it was a lot of things. Texas is a very big place, and over the last 73 years it’s been many things for me. I come from an old Texas family. Even though my father was a university professor, he never was very far from the whole cowboy aesthetic which he loved. He was even elected president of the National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association at one point.”

“Did your family belong to a faith tradition?”

“Deeply. My grandfather – my father’s father — was a Baptist minister. I grew up in a Southern Baptist fundamentalist home. My mom came from a family that was not quite so rigid, but the church was the center of their lives. So I was immersed in this Southern Bible Belt upbringing. My parents actually met while they were in a Baptist university. They married while still in school, and I was born before they graduated. But over time, their education and their own maturity led them to leave the church. They were churchless for many, many years until later in their lives. We stepped away from the Baptist Church, and I had my own path of spiritual transformation and transition over time. But my early childhood was church Sunday morning, Sunday evening, Wednesday evening. It was very, very strict. So I’m a recovering Christian although that early training and experience is deeply embedded in me. I told my dad one time, I said, ‘Well, you wanted a nice Christian cowboy, and you got a gay Buddhist.’

“My father died in May of 2020 at the age of 92. Although it was during the first few months of the pandemic, he didn’t die from COVID. I was not with him when he died, and, like so many people at that time, we met on Zoom. The last words I could understand him saying to me were, ‘I’m so proud of you.’ So we were able to make a good transition over time.

“The church meant a lot to me. I even thought about becoming a pastor just because it was in the family. We had many preachers, and I was called to many faith-related things as a child. This overlaps with my coming to acknowledge my being gay. There was a hymn we would often sing at the end of a Sunday morning church service in which the invitation was for people to come forward, to confess their sins and take Christ as their savior. The hymn was called ‘Just As I Am.’ I was always moved by that song, and I believed the message as a young boy. It wasn’t until I got old enough and had enough experience in the church to realize they didn’t actually want me just as I was. There were rules in the community, some spoken and some not. The truth slowly dawned; being seen was a bit risky, being accepted was definitely going to be conditional, and being loved ‘just as I am’ finally seemed impossible.

“I guess technically I’m bi-sexual. I had girlfriends. I got married to my high school sweetheart. We were both very smart kids. We clung to each other. We got out of town – a really small town in south Texas – when I went to John Hopkins graduate school. My wife worked for Goddard Space Flight Center just outside of Washington DC. We were achievement-oriented, bright kids. I suppose most people grow up and get married. We got married and grew up. We separated and divorced after only three years of marriage. We were married so young. Curiously, if we fast forward about forty years I ended up performing the marriage ceremony with her current husband. I said, “I married you twice. Once as the groom and once as the officiant.’ As kids we were really good friends, and our relationship helped us leave home back then.”

“So what I’m hearing,” I say, “is that it was less a matter of a loss of faith in the church than it was a sense of not being included. Is that right?”

“That’s a really good distinction. I didn’t lose faith in God; I lost faith in the church. I didn’t lose faith in what was larger and more true. I had some confidence in spirit or the divine. But the church, the people, I didn’t think they knew what they were talking about. I would later read scripture and find alternative translations and commentaries. A good friend who was in seminary once said to me, ‘You know you can look at that another way. It doesn’t have to be the way you’ve always carried it.’”

His introduction to Eastern spiritualities came through the TM movement in the ’70s.

“I needed help managing the stress of graduate school because I was such a perfectionist coming out of the kind of family I grew up in with the overlay of religious pressure and expectations. So I did TM as a way to meditate and relax.”

His early graduate work was in biology then he earned a second master’s degree and a Ph. D. in Clinical Psychology.

“So I had this psychology/biology background, that took me into behavioral medicine, and because I was fortunate to find positions in research institutes as well as hospital-based cancer treatment programs, I ended up working with a lot of people who were dying. I worked well with the patients and their families. I truly enjoyed the work. I directed hospital-based programs, I consulted at Sloan Kettering and MD Anderson and many cancer centers around the country. However, there were gaps in my skills and knowledge. There were things I couldn’t answer when asked by my patients. They were asking me questions from their soul, if you will. Really deep. Not just existential/psychological questions. And I didn’t want to give them religion. However, I did want to offer them an appropriate response that met the place from which they were asking.”

This led him to explore Buddhism. After all, he realized, “The Buddha only had one question which was what to do about suffering? I thought, ‘Well, I’m apparently in the suffering business.’ Furthermore, Buddhism was not theistic. The whole God idea wasn’t part of this spiritual practice path, and the spiritual technologies were accessible and not esoteric. This was a huge turn. And I needed a spiritual practice for myself because I was no longer in the church.”

He visited the local Shambhala Center and he engaged with Tibetan Buddhist practice for a bit. Then he went to a workshop at Esalen, a retreat Center in Big Sur that was a major part of the New Age movement of the ’60s. “I was doing psychotherapy training in support of my professional career, and there was a fellow there who was reading Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. He told me he had just finished a practice period at the San Francisco Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm and described what life was like at a residential Zen practice center. I found a copy of the book at the Esalen bookstore, and I began to read it. Even though I could not understand it, I knew there was something there. The voice of Suzuki Roshi was riveting to me. I was going to return to Esalen for a follow-up retreat about six months later, and I saw that there was a one-day retreat at Green Gulch the weekend before. This was my first immersion into formal Zen practice. I showed up at Green Gulch in the Spring of 1994, and the person in charge of guest practice asked if I could sit for forty minutes. I replied that I could, and he inquired if I could do so nine times in one day? I was young enough and foolish enough to say, ‘Of course, I can.’ That entire day was shockingly unpleasant.”

The retreat was led by Reb Anderson, the abbot at SFZC at the time. “His was the first Dharma talk I had ever heard. Honestly, I don’t remember what he talked about, but I do remember the last sentence. He paused for a while, and then he asked, ‘Is it ordinary or is it holy?’ And then he got up and walked out. And so even though it was a very unpleasant experience on an ordinary level, I had been captured by then. I had trouble with language to describe what had happened. I think I said to friends who asked, ‘It was as if I was remembering something. It is all foreign in so many ways, and yet it’s not “new.” It was a strange and deep familiarity.’ I knew I had found my path. This is what I had been looking for.”

He began attending retreats at the San Francisco Zen Center as frequently as he could while maintaining a full-time psychotherapy practice in Austin.

“Once I started going to City Center as a guest-student, I wanted to take the Precepts. On one of my early trips to City Center, we left the zendo after zazen as was the custom, and we went up to the Buddha Hall for morning service. Blanche Hartman was the officiating priest for that service. I was kneeling along with the others in one of the rows of students, and I’m watching her come to the bowing mat. She retrieved her zagu from the left sleeve of the koromo and placed it on the bowing mat, neatly folded. With her jisha, she approached the altar and offered incense. She came to the mat and offered her bows. While I watched her — the way she comported herself with such dignity, and the way she was looking at the altar as she engaged the ritual – I was transported: ‘I don’t know what that is, but I want that.’ I’d had many impressive male mentors, but this woman just bowled me over. I said to myself, ‘That’s my teacher!’ And so we began to develop a relationship.”

Meanwhile, in Austin, a friend who was an attorney found out that Flint sat zazen regularly and asked if he could join him. “I suggested that one morning a week, before he went to his law practice and before I had my first client meetings in my psychotherapy practice, we could meet at my office, set up a little altar, sit for a few minutes, then read one chapter of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. After only a few months my yoga teacher asked if she could join us. We invited her and both people kept coming. Then others found out we were sitting, and they joined in. At some point we needed a place bigger than my group room to meet.”

They moved to a larger location and eventually to a house. “Over time it seemed as if we had created a small temple, so I suggested it should have a name, and I insisted that we name it after my teacher, Zenkei Blanche Hartman. That is how Zenkei-ji temple was born.”

Eventually Blanche told him, “You’re acting like a priest. What priests do is they take care of communities, minister to them, and that’s what you’re doing. This community has grown up around you. Are you interested in the priest path?”

He was and, in 2001, he was ordained.

When his father’s brother-in-law – “a Baptist minister married to my grandfather’s daughter, my father’s sister” – learned that Flint had taken this step, he sent him a letter. “It was quite mean actually, and I spent a lot of time crafting a response that was not in reaction to his reactivity but invited a dialogue which never came. I explained that I understood his concerns and how this whole thing was probably inconceivable from his point of view. I said that I thought we were in the same business of being attentive to the struggles that people have just by living their difficult human lives. I acknowledged that we had different solutions or different ways of approaching human suffering. I said that if we were to look at what Jesus was suggesting in his teachings, he was saying, ‘Love everyone.’ Find ways to remove the barriers to compassionate care. Through meditation and prayer, wake up to whatever is larger than our small selves. The scripture doesn’t say, ‘Worship me.’ He said, ‘Be this way.’ And so all I’m offering are spiritual technologies to help people do that. Buddhism isn’t about believing anything. You don’t have to believe in anything. I argued that I could still be a Christian and use Buddhist practices, and that’s what I do. But it’s curious, isn’t it? When my grandfather died . . .” He retrieves something from his desk to show me. “We were sorting out things, and we discovered a small Buddha statue carved from ivory which had been brought to him by a missionary friend. He had it on his desk and now it is on my desk.”

“Even though it was an idol,” I remark.

“It was an idol, right. That was one of the things that my uncle railed about. ‘You’re worshipping idols.’ I said, ‘Well, I know it looks like that. But I’m not actually worshipping anything. If you look at those images, they’re representations of something that you’ll find in yourself.’”

“The Psalms,” I say, “‘Be still and know I am God.’”

“Exactly. Additionally I was invited to be on faculty at a place in Austin called Seton Cove which was a spiritual education center associated with a Catholic hospital. I was the Buddhist-guy because I could talk to all the Christians who were interested in Buddhism. And there was a course on Comparative Religions in one of the big Methodist Churches in town, and they asked me to come talk about Buddhism. At the end, I asked, ‘Are there any final questions?’ There was an older man, I would guess about 85 at that point, kind of hunkered down in his chair, who had been very quiet during the entire presentation and discussion, who raised his hand. I anxiously thought, ‘Oh, boy! Here it comes.’ Being polite in the appropriate Southern way, I acknowledged him: ‘Yes, sir?’ He then said, ‘Well, I just want to say, I think I have more in common with this young man than I do with half of all y’all.’”

In 2001, a new practitioner began attending Flint’s Austin Zen Center. Peg Syverson was a student of Joko Beck and maintained a small sitting group in her home. She was looking for a larger community to sit with and came, she tells me, to look upon Flint as her second teacher. The two of them worked well together and after difficulties arose because a teacher sent from SFZC to oversee the Austin Center proved to be a bad fit, Flint left the center he’d founded and joined Peg’s smaller group.

“Our combination was a good one,” he tells me. “Very synergistic. So it developed into a fresh way of practice which eventually became Appamada. Appamada is the last word of the Buddha in the Pali Cannon. It means ‘mindful diligent care.’ The Buddha told his followers as he died, ‘Practice with appamada.’”

The current website for Appamada states: “Our practice follows the tradition of the American Zen teachers Joko Beck and Shunryu Suzuki. In our teaching we draw on the Zen teachings and traditions we were trained in, as well as other Buddhist teachings and contemporary work in psychology, interpersonal neurobiology, language, the sciences of complexity and ecosystems, the arts, community, and philosophy.”

Peg describes it to me as a “relational” practice. “Our understanding is that we wake up in meeting, in encounter – not by sitting and facing a wall and somehow blanking our mind – but in encounter. It might be an encounter with a peach tree; it might be an encounter with a Zen master; it might be an encounter with an old lady at the well. Zen is full of these stories. Right? They’re all about encounter. And that was the big distinction in the pedagogical shift from India to China. So in India, Buddha stands up and gives a talk, and people are either enlightened or they go off into the forests and meditate. But in China someone would stand up in the middle of the talk and challenge the teacher. Or there would be an encounter between two Zen masters, and it’s always about this encounter.”

The formalities involved in authorizing teachers within the Suzuki Roshi lineage are complex, and Joko Beck’s tradition presented its own difficulties, but eventually both Flint and Peg received full Dharma transmission, although by the time they had, the situation at Appamada had changed.

“I moved to Hawaii in 2018,” Flint informs me. “I started coming to Hawaii to lead retreats at a little retreat center in 1999. Over all those many years, I would teach for a week with my friend Donna Martin. Donna was a yoga teacher, and I taught meditation, so we would lead a retreat we called the Heart of Meditation. We did that starting in 1999 and only stopped offering that retreat two years ago. Each year Erin, my partner, and I would just stay in Hawaii for a little vacation, and we enjoyed the islands. Over time it became a special destination. We considered that we might be able to cut back on work as we got older and actually live in Hawaii. In 2016, a house became available. A little house – we were not looking seriously – which was ideal for us and something we actually couldn’t say ‘no’ to. It was a big transition for me not to be at Appamada although Peg was still then. I moved in 2018, and little did we know what was going to happen two years later. We could not have predicted the pandemic and its impact on our little center.”

When the pandemic prevented in-person gatherings, Appamada, like many other Zen Centers, met by Zoom. This allowed Peg to move to Illinois to be closer to family. Today there is both in-person and distance participation at Appamada, and, although neither Flint nor Peg are in Austin, they both retain a relationship with the community.

“We are senior guiding teachers emeritus, but no longer resident teachers,” Flint tells me. “We have three lay-entrusted teachers who care for the sangha.”

In Hawaii, Flint has a small sitting group. “There is a Soto mission on each Hawaiian island, but they’re mainly for the Japanese-Hawaiian communities and not practiced based. The one here was built in 1927, and so in a couple of years it’s going to be a hundred years old. It seemed to go dormant for a number of years, but it’s been revived, and I have begun to offer zazen on a monthly basis just to start.”

“Anybody show up?” I ask

“We have about a dozen people each time. Some haole, white people, and some traditional, local folks who consider the temple their church. I don’t really want any authority. I don’t expect to be elevated to any leadership position. The Bishop of the Soto-shu and two other priests take care of the formalities. But I wanted to offer zazen and some folks have been happy with that. They’re letting me help out, and it’s been a sweet connection. I certainly don’t want to start another center at this age. I’ve done it twice! I’m 73 years old; I don’t need to do that again.”

“What is this all about?” I ask. “What is it that a Zen teacher teaches?”

“Gosh, that’s a hard one, isn’t it? I don’t know that content is taught. Certainly we have content to share, but that is not what we teach. The basic Buddhist philosophy is important as a way to situate our practice and to guide us. The Four Nobel Truths, the Eightfold Path and the Twelvefold Chain and all that is included in what the Buddha left for us. And as a Zen teacher you can call on the old stories – the koans – or you can be the ambassador for Dogen’s unique insights and offer our best understanding of what he taught. I think all of this is useful. The poetry and art of Zen is gorgeous, and it offers something powerful and beyond cognition. But in the end, they are all props. Someone a couple of years ago asked me an interesting question. They said, ‘Look, you’ve been a psychotherapist for forty-five years. You’ve been a Zen student and a teacher of Zen for half of that time. Tell me, what do you really do?’ It was a very interesting and important question. What arose spontaneously without my thinking too much was, ‘I would say my job is to help remove barriers to love.’”

“Are the reasons why people come to psychotherapy very different from the reasons why people come to Zen?”

“No. Not really. People come because they’re suffering in some way. Because they have problems in their lives or questions which they don’t know how to meet in any satisfying way. When I sit with a client in psychotherapy or sit with someone who comes to me in dokusan, they bring the same stuff. They bring their life and the troubles in their life. They bring their body and mind and heart and all that comes with these very human things. The difference is who they meet.”

“You mean the role you assume when meeting them? You wear different hats.”

“Yes. If I were sitting in the role of a psychotherapist, I’d get the history and their symptoms along with whatever it is they want to change. I would consciously enter into the archaic aspects of their conditioning and work with that. All of that is useful and extremely important. But as a Zen teacher, I’m not necessarily going into all personal history looking for problems to solve or behaviors to change. All of this is acknowledged but is not at the heart of practice. We’re looking at what’s here and now, and the ways we are caught in the self-centered dream that causes us to suffer unnecessarily. How can they use each moment of life as the teacher?”

“Can someone come to you in both capacities?”

“They have, yes. And as I sit in my roles as a Zen teacher, I can’t divorce or forget the skills I have as a psychotherapist. So it informs the way I sit with a person certainly. But I’m not taking them on as a client or doing all the archaic work or behavioral work. I do however think I’m more skillful as a Zen teacher because of my experience of many years of psychotherapy.”

“And what is it you hope for those who come to you in either capacity, either as a Zen teacher or as a therapist?”

“My hope is that they would be in a relationship with themselves and the world that is filled with more ease. That they’d have a capacity to accept and meet life as it is without fighting with themselves or with other people or with the realities of this life. The way I talk about inhabiting these two roles is this: I’ve been a therapist for so many years. I’ve had the great gift of working with so many people who’ve done amazing work. They have transformed their lives and have had an immense amount of insight and awakened awareness as a result. However, I frequently see that often they can end up in an endless cycle of self-identification and self-reflection and self-help because that’s what a therapeutic perspective invites. In my role as a Zen teacher I’ve spent years in temples and monasteries where I’ve seen people study the Dharma, practice well, and demonstrate an amazing understand of the Dharma and a capacity to reflect it in their practice life. But, when they sit in zazen and all their psychological energies move — the unconscious showing us what we often don’t want to see — they often have no idea of what to do with it. But if you put those two things together — the capacity to do the psychological work and the capacity to step beyond the self — then you have what I call the double helix of growing up and waking up. And those two strands inform and support each other in ways that each of them alone cannot.”