Palolo Zen Center, Hawaii

The Zen boom of the 1960s and ’70s was largely a youth phenomenon. It’s said that one of the reasons Dainin Katagiri established his Zen Center in Minneapolis was because he had not been at ease with the counter-culture young people who flooded the San Francisco Zen Center. He wanted his Zen to reach what he considered “ordinary Americans.” Hawaii in the ’60s had no lack of hippies who found their way to the door of Robert Aitken’s Diamond Sangha, but the membership also included skilled tradesmen, a marine design consultant, and even a long-haired refrigeration engineer.

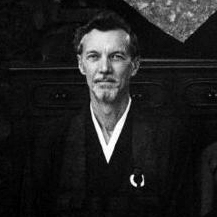

Michael Kieran is the primary teacher at the Palolo Zen Center in Hawaii. He is a second-generation Aitken heir who grew up in California and went to college in Sacramento where he studied engineering.

“One of the courses I had to take was called ‘Survey of Engineering,’ and the fellow who taught it was a registered mechanical engineer, and he also taught this program on refrigeration technology. And I thought, ‘I think I’m going to do that.’ Before I even finished the program, I had a job offer from a large supermarket refrigeration equipment manufacturer in Southern California. I moved down there and worked as an assistant to a fella who was 70 years old and had done this work for fifty years, and his joy in life was teaching it to somebody else. So that’s how I’ve earned my living.”

After working as an assistant engineer for a year and a half, Michael went back to college. “I just started taking courses that seemed of interest and ended up liking philosophy courses.” One of the courses was called Chinese Humanities. “It was actually a course on various schools of Chinese philosophy. When we got to the section on Zen – or Chan – Buddhism, I was blown away. I thought I’d really love to know more about this.” The course instructor told him that if he wanted to learn more about Zen he should consider going to Hawaii.

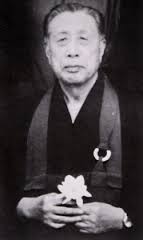

“I had no idea there was any living practice of Zen, but I had hair halfway down my back at that point and a VW van which I shipped to Hawaii.” He flew to the islands a few weeks later. “I walked from the airport to the dock and picked up my van and lived in it for a couple of weeks before I had to register for school. One of the first courses I took at University of Hawaii was on Chan Buddhism taught by a fellow named Chung-Yuan Chang. Really a wonderful man. And in that class I met somebody who attended the Zen Center here and told me about it. That was 1973. In 1974, Robert Aitken was authorized by Yamada Koun as an independent master. So my first sesshin at the Koko An Zendo was his first sesshin as a teacher, and I’ve just stayed with it through the years. I continued to work in commercial refrigeration. I was able to make a good living doing that and enjoyed it a lot, but it wasn’t . . . You know, for some people their work is their life. I enjoyed my work, but it wasn’t my life completely.”

“What was the draw to Zen?” I ask. “What had you read that made you want to learn more about it?”

“I think the prospect of awakening.”

“So you get to Koko An and now it’s a practice rather than a study.”

“And the practice is very simple and direct and a kind of a nice contrast to the philosophy, and yet the connection was clear. You know, rather than the Six of This and the Eight of That that you find in early Buddhist teachings, you have Mazu shouting or kicking some guy in the chest, and his waking up. This is phenomenal! There was a practice and people and a whole tradition through Japan that I really didn’t know about, and then meeting Robert Aitken, someone actually practicing these teachings, and being authorized by the tradition to teach it to others, it really fleshed it out for me. Here’s a man who’s lived in Hawaii most of his life, has practiced Zen in Japan, and he’s bringing the tradition to us as he’s learned it from his Japanese teachers. And so now there was a real bloodline to the tradition in my mind and in my body and practice.”

I ask Michael to tell me about Aitken.

“Where do I start? He feels like an old dear friend. He was of another generation, and a remarkably spirited person. I don’t mean spiritual. I mean just willing to do whatever needed to be done. In being of another generation, he seemed to me to be a little stiff, a little bit more in his head, and yet the spirit and the energy he brought to the practice was just this raw kind of wild energy. Just a ‘go for it’ kind of thing that spoke to me and a lot of young people. I think times have changed, but at that time – in the early ’70s – many of us had ingested various substances, had experiences that were . . . uh . . . of interest, and yet not an end in themselves. And it seemed that the Eastern religions had some kind of a method and a way of tapping into this other element of life that was beyond what the culture and the society seemed to be about.”

I wonder, given his straight job, if he felt at home with the hippies at the Zendo.

“That’s where my heart was, so I felt very at home with like-minded people and all that. It was a little more of a mismatch for me out in the world in a way. But not so much. I kind of felt at home there too. Two things about it, just being a long-haired haole from the mainland . . . Haole, do you know that word?”

“It means not native-Hawaiian, right?”

“Yeah. It’s not necessarily derogatory as some people take it. It’s just factual. These white people come from over there, and they have a completely different way of thinking and acting, and they’re haoles. And I was certainly one of them. But the local people really took me in. I loved working with them. Most of my time was in the office doing engineering. You know, they’re putting in a store. They need walk-in coolers or they need display cases; you kind of figure out what they need, and you have to put various components together to make a system, and that’s what I did. Sometimes I would go out and work with the installers, which was a lot of fun. I didn’t feel a need to talk about Zen to people I worked with; they seemed fine the way they were. And maybe that’s part of Zen as it is as well.

“You know, the Diamond Sangha is a lay tradition. One of the few, really. Most of the people who practice Zen are lay people, but, in terms f the teaching and all that, people still get ordained. Some groups and lineages adhere quite closely to their Japanese counterparts. Some have gone completely the other way and removed anything Japanese. Anyway, that stream of lay practice was something that Robert Aitken embodied. And his teacher, Yamada Koun, was a layman so when he would come from Japan and lead sesshin, it was really wonderful to see him. His teachings were stunningly clear, alive, and powerful. And he was just a regular layman, and he was very comfortable with that. So I feel fortunate in that regard. And I see the Soto tradition still struggling with lay people and lay teachers and ‘lay empowerment.’ So that was kind of all settled before I started, and I appreciate the value of it, and the value of recognizing one’s work in the world as your practice.”

Michael tells me he practiced “intensively” for about a dozen years. Aitken recognized his dedication and after he moved to Maui, in 1979, he asked Michael to help him by having “interviews” with the students who remained in Honolulu.

“He wanted people to be able to do dokusan, so I started doing dokusan with people at the Koko An Zendo in Honolulu. We didn’t call it dokusan, and there was no talk of transmission. He couldn’t give transmission at that point, but he authorized me to work with people in the dokusan room, and I did that for about four years. I got married in 1979 to a lovely woman that I’d met through the Zen Center; she’d been living on Maui. And we had a child in ’82. And by ’84, my daughter is two years old, I have my own refrigeration business, contracting company. I hadn’t had a paycheck in probably three months. We were living off my savings, just getting by. And one evening I was charging off to the zendo on a Wednesday evening to practice with the sangha, give dokusan, and . . . And I just looked at my life and said, ‘You know what? This is not working. You’re going broke. You’ve got a young child. Your business isn’t working. And you’re spending most of your time at the Zen Center.’ So that was kind of a turning point for me, and I told Roshi I needed to step back from my involvement at Koko-an. So from the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, I stepped away, and I devoted my energy to my company and my family, and it was just what I needed to do. During that time I was not involved formally at the zendo. I continued my practice with my wife and would come to different ceremonies from time to time. I was asked to give a talk here and there. It didn’t feel separate at all, but I just couldn’t put the kind of time in, and I allowed myself to just let that go. Then in the mid-’90s, Aitken Roshi announced his retirement. He was going to move to Kaimu, and he was going to give one more Rohatsu sesshin, and I just knew that I wanted to be at that sesshin. So I signed up, and during the course of that sesshin, I realized, ‘Well, I’m back!’”

He smiles and laughs gently.

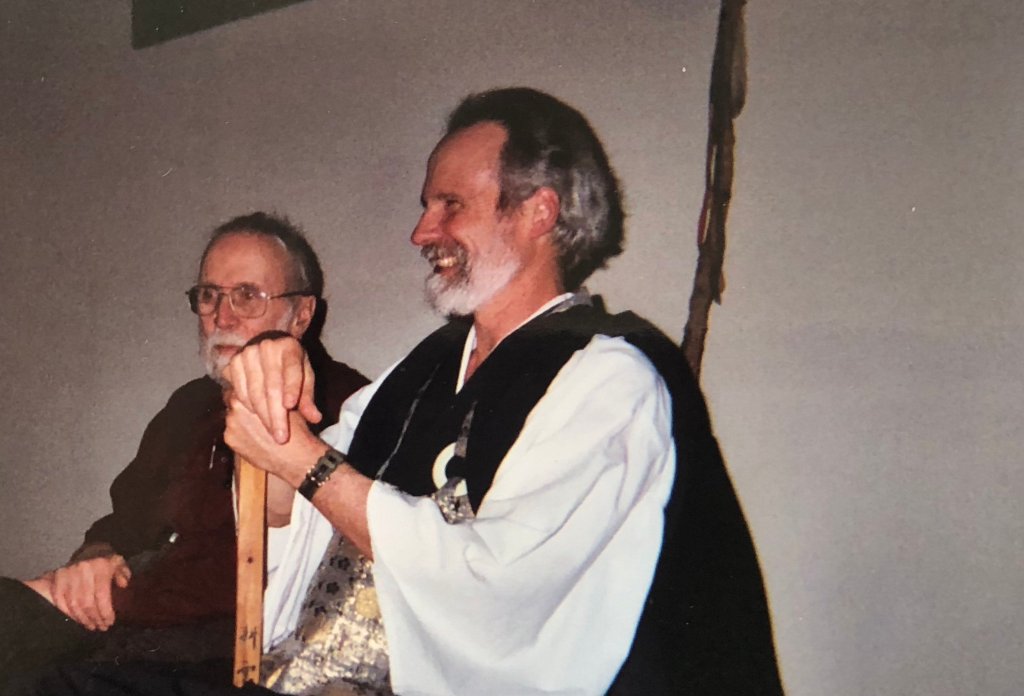

“I had really missed formal practice with the sangha, but during those ten years I was able to get my company really going and started to have employees and started to get more work, and it could roll along by itself a little better. And it was at that point that Nelson Foster became the teacher and Roshi retired to the big island although he continued teaching on a much smaller scale. So I started with Nelson who’s my old friend. We actually shared a home together for many years. We lived in the same house together when my daughter was born. Anyway, he was a very close friend, but it turned out that he was a wonderful teacher for me. Very encouraging, and I was learning things. In 1999 he authorized me as an apprentice teacher, and in 2004 as a Dharma successor. So I was Nelson’s first Dharma successor.”

I ask him to tell me about Nelson.

“He’s my teacher, he’s a dear friend, someone I trust and work with. Maybe that’s the thing that stands out for me, that we work together, and we confide in each other and inspire each other and prod each other. And also have a kind of shared history before working together in Zen teaching, having just been students together under Aitken Roshi. Dharma brothers. Yeah. He’s someone I trust very deeply.”

“How did you come to share a house with him?”

“As Koko An sangha members. Back in those days, it seemed like a number of sangha members shared houses in the Honolulu community. We had a house, and we had a room for rent, and he wanted to rent it. So, one of the things I think of there is just the practice of the household and how we conducted ourselves within our own house. One of the things that naturally happens when people live together, there are various frictions, and things come up. A tradition that continues for both of us, sitting around the dining table and talking about something that was bothering us that was happening in the house or this or that, and one of the ways that we would encourage each other to get into it and ‘tell us what’s really going on with you about this’ was to say, ‘Come on, Nelson. Get down! Get down into this, and what’s this about?’”

“Did your wife take part in these discussions as well”

“She absolutely did. She was one of the main prodders,” he says laughing, “and another of my great teachers. Yeah. But we would do it for each other. Listen. Just shut up and listen and make space for one another. It felt like, ‘Let’s be real here. There’s no reason to withhold things. This is it.’ So, yeah, that was that. So even now in working with sangha members and encouraging the sangha to be a sangha, we both encourage what we call the ‘good stuff conversations.’ Let’s get into the good stuff here and talk about where you felt hurt or what’s buggin’ you. And to do that with one another, and to listen to each other. So that becomes a really important part of our practice and teaching.”

“So,” I reflect, “back when you and I started in this practice, what people were looking for – maybe because of the prevalence of psychedelics – was awakening. We probably called it enlightenment. That isn’t a driving force any longer, is it?”

“Not nearly as much. Mindfulness has taken over. It’s all about mindfulness. And it’s a good thing. And you know LSD has . . . Well, maybe it will make a comeback. But that culture kind of ran its course. Certainly that search for awakening was why people came, and I think, of course, of Three Pillars of Zen which was instrumental for me in recognizing that there was a living tradition of awakening and a way to practice and a way to work with it. A way to open it up when you did have some kind of insight or experience. It wasn’t just the be-all and end-all; it was just actually the beginning. Not the end. And so all of that was very inspiring to me. And, yeah, times change.”

“When a new person shows up today, what are they looking for?”

“It varies, but it feels more psychological. Victor Hori has said that in Western Zen there’s definitely the Buddha and the Dharma, but the Sangha jewel has become psychology. So rather than a sangha context – because people don’t live together and they don’t experience the kind of rock-tumbler of having to get along together like they did in the old days or like people living together in a monastery do – then it becomes a kind of psychological framework.”

He means, of course, that there isn’t a “sangha” in the traditional sense of a community of monastics who have “left home” and retreated from the world. I ask if there isn’t a sense of community at Palolo.

“Yes, as a community. That’s very important to me. People sometimes come because they seek community, but they come, often, just to settle their minds. It’s hard to say to what degree anymore people actually come with the sense that some kind of awakening might be possible for them. There are those who come who think they are already awakened, and that’s interesting. Nevertheless many new people are still coming and are looking for something. But, boy, it’s not the same. We continue the practice of orientation talks which was started by Harada Roshi and has continued in our stream of Zen down through the years. It’s very different now, but once a month we have an orientation program for new people, and we almost always have ten to twenty people. And out of those ten to twenty, maybe one comes back. Maybe one or two will come back once or twice. Or maybe three times. But over a course of a year, it might be one or two people might stick.”

“So you’re saying they come to the center for essentially psychological reasons, which is pretty much what I’m hearing from other places as well. People are looking to reduce anxiety or whatever. And what, specifically, do they expect from you?”

“Well, that ends up being a kind of discovery. One of the things I always ask them is, ‘Why are you here? What do you hope to gain?’ So when you ask me what are they there for, that’s what I’m speaking from, my experience in asking that question. Because how I work with them is based on what they’re there for. That does change over time. Often people who come today and stick with it are pretty diffused. I think part of it is cyber-culture, just a lack of ability to focus. Riding off on their horse in ten directions at once. But people seem to have a way-finder, and their understanding of what brings them to the Zen Center is usually a few steps behind their actual feet and their actually showing up. But something speaks to them through the orientation and practice that doesn’t go away. They may go away for a while, but then it comes back again and again. And then it’s a matter of trying to fit it into your life in a way, to set up your life in such a way that you can sit every day, come sit with a group at least once a week. And that ends up being pretty standard for people.

“One of the things – going back to Aitken Roshi – one of the things that turns out, to me, to be extremely powerful and important, in particular for lay practice, is consensus decision making, participatory decision making. I don’t use the world ‘consensus’ in a technical way; it’s really a kind of participatory decision making at the sangha level. And that flies in the face of the hierarchical kind of organizational structure that many Zen Centers have, and I think it was something Aitken Roshi believed strongly in.” He smiles broadly. “But as many have noted besides me, he wasn’t particularly good at it. You know, somebody would say something in a meeting, and it would rub him the wrong way. He would just ‘URRGHH!’” Michael grits his teeth and frowns in imitation. “He’d just grimace and sort of go, ‘AHHH!’ It would just flatten everything, and the conversation would just stop at that point. People care about what he thought. And he couldn’t – somehow – not show his reaction.”

I point out that during my career in community based social development in southern countries, I had the opportunity to observe many consensus-based meetings, but it was my experience that there was usually what I came to refer to as “the guy,” someone whose contributions carried more weight in the discussions than those of the other participants. I suggest to Michael that Aitken would have been “the guy” and that probably Michael is “the guy” at Palolo now.

“Yeah. Whether I want to be or not.”

“Isn’t that the thing about consensus?” I suggest. “Everyone wants a chance to have their point of view heard, even if they know its not going to necessarily carry the day. They want to be heard and respected, but people also generally have a feeling that there’s got to be that guy who finally decides how it’s going to play out.”

“Yeah. That seems natural in a way. There are differences in people, but that person – if they are listening to the community – should then reflect what is said. I think ideally if you have a good facilitator, they will keep collecting and feeding back to the group what they’re hearing in the group. And so it’s an on-going practice – for us anyway, growing up as voters – to try to listen to the group, and what is the group wanting, what is it saying? And what are the concerns? So as we try to make a decision together, one of the things the facilitator is always asking is, ‘So it sounds like this is the proposal that’s being put forward and it’s modified as such. What concerns and objections are there in the group?’ So we’re always trying to pull out the concerns and objections and get those on the table. And almost always they lead to a better proposal. So there’s something in working together on an issue that is, to me, the one way that we can work together and experience sangha, experience something that’s collective. We do that at our board level, and we do that as a sangha for sangha decisions. Uh . . . It works better sometimes than others, but to me that is one of the key elements of lay Zen practice and maybe Western Zen practice where we get to realize the sangha as a treasure. The real treasure of the sangha as a sangha. It’s not just a collection of individuals who come to realize Buddha and to study the Dharma. It’s its own jewel. It’s not just a derivative of the other two. And yet you can’t have a sangha without the other two – you know? – that’s a club or something else. I don’t know what that is – and it’s fine – but it’s not a sangha.”

I ask if he has identified a Dharma heir, and he tells me he has an “apprentice” – Kathy Ratliffe – who he hopes will become an heir.

“So you’re ‘the guy,’” I say. “You’re the person who has the responsibility to ensure the tradition continues. What is that you would hope for the people and the community with which you work?”

“I certainly don’t want to lose the importance of the awakening experience.”

“Even though awakening is not necessarily what draws people to practice, you still want to maintain it as a central element?”

“Yes. I want people to be aware that there is such a thing. That it’s possible for them, and that it’s a way, not a destination. The way of awakening. People are interested in destinations. They want to get somewhere. And the way of awakening which leaves you nowhere to stand and is only a way, no parking allowed, that – to me – is what has to be preserved if Zen is going to stay alive. And I think our tradition has a very interesting way of doing that in koan study, which can certainly become formalized and dead. But it doesn’t need to. There’s nothing inherent in it that needs to do that. So that – to me – is a gift that I feel I’ve been given and that I want to give away. I don’t want any of it to stay with me.”

“You feel a responsibility to maintain the tradition.”

“I do. And keep it alive. ‘Maintaining’ means to go beyond your teacher. To keep it alive. To keep it fresh and new. And yet to be informed by the tradition and to know the tradition.”

I knew Michael briefly 20 years ago and would add that he has a good sense of humour.

LikeLike

Michael was my teacher many years ago, when I lived in Hawaii. I always appreciated his compassion, authenticity, and skill, as a Zen teacher. He’s also not afraid to tell you the hard truth, and he changed the course of my life. I will always be indebted to him and the Honolulu Diamond Sangha. If anyone wants to dig deeper into their own minds and find out for themselves what life and reality are truly about, take that long, winding drive to the back of Palolo Valley and find out for yourselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person