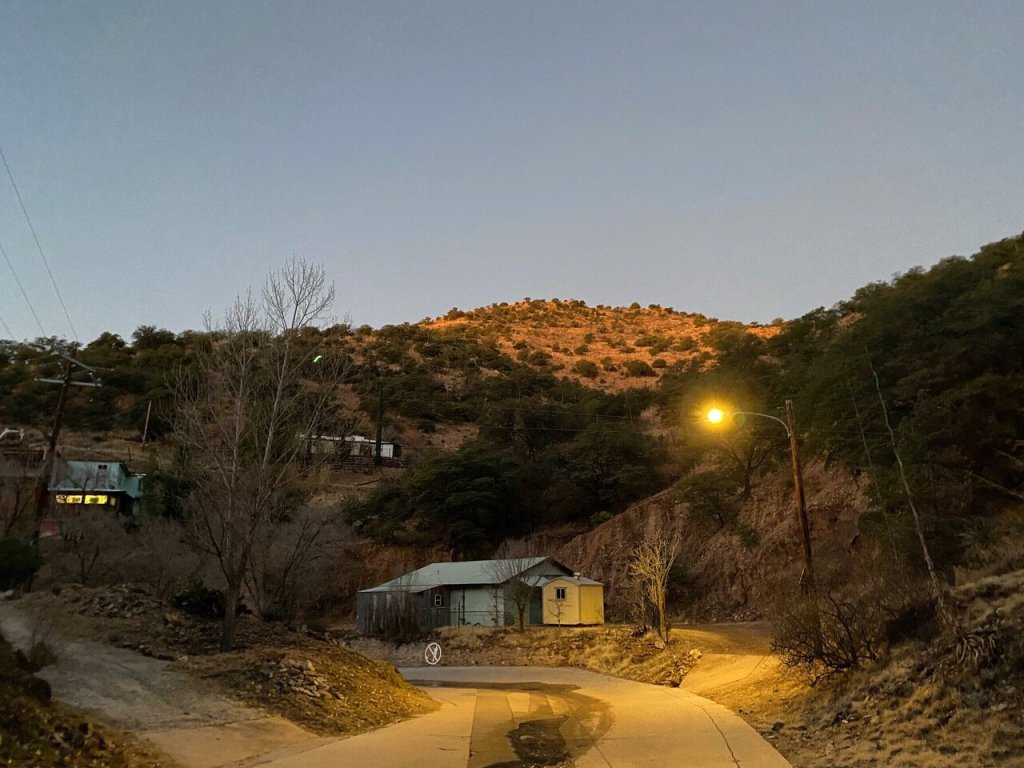

Cochise Zen Center, Bisbee, Arizona –

Barry Briggs – Kwan Um Zen Master Hye Mun – first encountered Buddhism through a girlfriend. “She practiced in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition with Sogyal Rinpoche, who died several years ago.” Barry was studying the Philosophy of Religion at the time at university. “I’m interested in human behavior and what motivates it. And at least in the 1970s, there was a lot of interesting philosophical work to be done in the field of religion and belief. So that attracted me. I worked a lot on the ‘problem of evil,’ how to reconcile the existence of evil with an all-powerful, all-good, all-knowing deity.

“In the early 1980s I practiced with Sogyal Rinpoche – ‘practiced’ in a loose sense – for five years. When he came to Seattle, I would go to a weekend retreat. My recollection – perhaps not to be trusted – is that he would talk a lot for two days. I remember being fascinated by it, how he would describe human mind, how mind functioned. And then, at the end of the two days, he would say, ‘Now go home and practice.’ And, of course, I didn’t. Or not for very long,” he adds with a chuckle.

“What did he mean by ‘practice’?” I ask.

“He would teach meditation over the weekend, but these were not meditation retreats as I understand it now. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that these were ‘Dharma retreats.’ And at the end he would say, ‘Now go home and practice this meditation that I taught you.’”

“And you didn’t.”

“Well, for a few days. Maybe. You get a little bit of Dharma gasoline, and you can go for a short distance. And then you run out of gas. Then a couple of years later, my best friend invited me to go to a Zen retreat with him. And that was almost like the inverse of Rinpoche’s retreats. Very little talking and a lot of practice. A lot.”

The retreat was in the Korean Soen tradition.

“There was a Korean nun who had a hermitage in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains outside of Seattle, and we went there in January. I remember very clearly that she didn’t heat the place. There was snow on the ground. It was bone-chilling cold, and all we did was practice: bowing, chanting, and sitting. And I found out that I loved practice. Not talking about practice but actually doing it. It’s what I wanted.”

“What was it about it that you found appealing?”

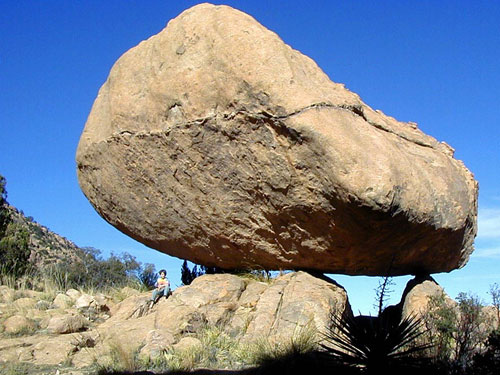

“It was embodied. Although I was a philosophy student and – for a time – quite intellectual, I’ve always been somebody who has used my body a lot. I’m old now, so it’s different, but in my 20s and 30s I was a rock climber, a cyclist, a professional modern dancer, and just physically very active. People might not think of sitting in meditation as physical activity, but for me it was physically very active. Plus, in the Kwan Um School tradition, we do 108 prostrations every day and lots of chanting. Very physical practices.”

“It takes energy to sit still,” I point out.

“It does, and I loved it. I wasn’t looking for a spiritual practice, but when I went to that Zen retreat, I said ‘Oh, I want to do this. This is something I understand.’ There was a small sitting group in Seattle – a Kwan Um School sitting group in Seattle – at that time. Maybe ten people. Of the ten, maybe three were interested in Kwan Um School style. Some were Glenn Webb’s students or had been his students. Most of those ten eventually wandered off to various Japanese forms of practice available in Seattle at that time. So really it was just a few of us. Then it started growing. We moved around from place to place.”

Glenn Webb was a professor of art history at the University of Washington who had trained in the Obaku school of Zen in Japan and introduced many Western students – including Genjo Marinello – to formal practice.

The group was small and not formally organized. “We had a set schedule, and we just showed up. Our guiding teacher was a man named Bob Moore, now known as Zen Master Ji Bong, who lived in Southern California. He would visit several times a year, along with other Kwan Um School teachers.”

“And if someone at the time had asked you what you were getting out of this practice, what would you have told them?” I ask.

“Hmm. I would have made up a fairy tale about becoming more calm and centered, blah, blah, blah. Like that. I would have invented a story because, particularly in the first ten or twenty years, how could one possibly know? Obviously, training has impact on peoples’ lives, but any attempt to describe a benefit most often just leads to a fairy tale. At least in my experience. The Zen tradition has enough fantasy wrapped around it, at least in the West. So perhaps it’s best to keep one’s mouth closed and encourage others to find out for themselves.”

And so those ten or twenty years passed. He remained faithful to the practice and worked in the software industry. “I retired in 2005. Then I was asked to become a teacher in 2012 and that happened in 2013.”

“Who asked you?”

“In the Kwan Um School, when a practitioner seems ready, a committee is formed to assess that person. My primary teacher at the time was Timothy Lerch Ji Do Poep Sa Nim and my sponsoring teacher was Zen Master Bon Haeng, Mark Houghton, who lives in Massachusetts. If the committee agrees, then the individual receives inka, teaching authorization. For me that was in 2013.”

In 2015, he was invited to leave Seattle and move to the Cambridge Zen Center in Massachusetts.

“They asked me to be their resident teacher. It’s a wonderful Zen Center, an incredible Zen Center. It’s one of the oldest and largest residential centers in the United States, founded in 1974, I believe. And at any given time, thirty or so people live there, right in the heart of Cambridge. The Kwan Um School has quite a few Zen centers within two hours of Cambridge so there was a lot of teaching to be done.”

He was the Resident Teacher and later Co-Guiding Teacher with Jane Dobsiz, Zen Master Bon Yeon.

I ask what his responsibilities had been.

“The Zen center has formal practice every morning and every evening, seven days a week. I showed up every morning and every evening, six and half days a week. I took Sunday evenings off. On a regular basis I offered kong-an interviews, talks, and workshops. I met informally with residents and members of the non-residential community. But the primary responsibility I took upon myself was to show up for practice every morning and every evening six and a half days a week.”

Also during that time, he traveled extensively, teaching in central Europe, Russia, South Africa, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, and throughout the United States.

On the other hand, as much as he loved the Cambridge Center, he didn’t feel at home in New England.

“I still have good relationships with people in Cambridge, but New England was not my home. I really missed the west. In the winter of 2016-17, I said to myself, ‘I’m going to rent an Airbnb in Southern Arizona and be warm. And do a kind of loose retreat.’ Sit in the mornings and the evenings. Walk in the mountains during the day. And as I was scheming that out, a friend in Seattle wrote and said, ‘What are your plans?’ I told her and she said, ‘I own a house in Bisbee Arizona. You could use my house.’ So, okay. I’d never been to Bisbee, but – as happens to many people who come to Bisbee – I came here, and I liked it. So, I hatched a plan to move here. As it turned out, there was already a Zen center in Bisbee. It had been here for fifteen years but had never had a teacher or a formal affiliation. It was simply organized and operated by local people who wanted to practice.”

“And did they welcome you with open arms?”

“Almost everyone was happy to have somebody who had an actual credential,” he says, chuckling. “Some of the people who welcomed me with open arms maybe weren’t so welcoming later as they realized I was an ordinary person.”

Bisbee is a small community, with a population of less than 5000 people, and yet the Zen Center has twenty-five active participants. In Zen circles, this is huge.

“I’m astonished, to be honest with you,” Barry tells me. “I’m astonished. It’s amazing. We’re the only organized meditation group for a hundred miles, so if somebody wants to practice, they come to us. For this reason, I try to keep the community very spacious in welcoming people regardless of affiliation or background. We’ve had Transcendental Meditation practitioners, somatic body work people, Tibetan practitioners, and lots of non-Buddhist types practicing with us. We welcome them all. Of course, I wear formal Zen robes and speak from my tradition when I give talks. I’m only authorized to do what I do, and so that’s all I do. I can’t pretend to be a different kind of person. But because of our unique situation, I hold the forms very loosely. When I was at Cambridge Zen Center, there was a Buddhist Center about every other block or so. If somebody didn’t like our center, they could go to Insight Meditation which is literally about six blocks away. It’s no problem. But here in Bisbee, that’s not an option for people. For this reason, I keep the forms loose. And if somebody’s not following the forms, I usually keep my mouth shut. I want everyone to feel like this is their practice home.”

There may be substantive differences between Japanese Zen and Korean Soen, but Barry is reluctant to address the issue. “I don’t know that I can speak to that with authority because I don’t have direct experience with Japanese Zen.” He is, however, willing to outline his understanding of the Korean tradition as it was organized and taught by Zen Master Seung Sahn.

“I’ve heard that when he came to America in 1972, he was a very high-ranking teacher in Korea. And according to the story, in the Korean version of Life or Look magazine, he read about hippies in America and said, ‘Oh, I can teach those people.’ So, he moved here, not speaking any English. I wasn’t around in those days, but apparently his original idea was that he would create a monastic order in the West. But Western people didn’t go along with that idea. ‘Monastic order’ in the Korean Buddhism means the traditional 250 or so precepts. I’ve heard the words ‘monk’ and ‘nun’ are used in a certain way in Japanese Buddhism; sometimes ‘priests’ is used also. These terms have a different meaning in the Korean tradition where they refer to celibate monks and nuns who live very restricted lives. So when Zen Master Seung Sahn came to America, most of his American students were not willing to follow in that path.”

“He wasn’t able to follow that path himself when he got here,” I point out.

“That’s my understanding,” he agrees. “But I wasn’t around when that behaviour occurred, so I don’t really have anything to add to what you’ve probably already heard. But despite those issues, he interpreted his Korean heritage in a way that seemed to make sense in the West and built a lasting framework for practice. And those are the same elements of our practice today. Recently I talked with someone at a Rinzai center, and they said, ‘You know, the view we have in our center is that the Kwan Um School is “Zen-lite” because you don’t do a lot of sitting.’ And I said, ‘Oh, that’s interesting. How long is your longest intensive retreat?’ He said, ‘Seven days.’ I said, ‘Well, take that seven-day retreat and do it for twelve weeks consecutively as a silent meditation retreat. That’s what we do every winter at centers around the world. And if you go to Korea, we do it every winter and every summer. Monks and nuns in Korea are in intensive meditation retreat for six months a year. Maybe that’s Zen-lite. I don’t know.’ So, we sit a lot. We chant a lot. We do 108 prostrations every day, although my body is old, and I can’t do full prostrations any longer. And we work with kong-ans. So those are the four elements of our practice.

“But underneath all of that is what I call ‘vow.’ Why do you practice every day? Only to get a good feeling? Or to have some calmness? Is that the only reason you practice? That’s what I ask. Zen Master Seung Sahn used to say, ‘Why do you eat every day? Why did you get out of bed this morning? Because your body is hungry? Or your alarm went off. Is this why you got up?’ Underneath everything we do is ‘vow.’ Why do you have a human body? What are you going to do with your human body? If that’s clear, you don’t need to practice. These are the elements of our tradition as I understand and teach them.”

I ask if he’s ordained.

“No, I’m not an ordained monk. In the Kwan Um School – I know this sometimes can be confusing for those trained in Japanese traditions – in the Kwan Um School the precepts path and the teaching path are independent. Somebody can have 250 precepts as a fully ordained monk or nun but never become a teacher. They’re just completely different paths.”

“So what’s the function of the precepts path?”

He answers without hesitation: “Living an upright life and helping this world. Serving as a model for helping this world. The function of the basic Five Precepts is to bring yourself upright. The next five precept are about community relationships, how to function harmoniously in community.”

As they were explained to me by Judy Roitman [Zen Master Bon Hae], the First Five Precepts in the Kwan Um School are: 1) to abstain from taking life; 2 to abstain from taking things not given; 3) to abstain from misconduct done in lust; 4) to abstain from lying; 5) to abstain from taking intoxicants to induce heedlessness.

These are followed by: 6) vowing not to talk about the faults of others; 7) vowing not to praise oneself and put down others; 8) vowing not to be covetous and to be generous; 9) vowing not to give way to anger and to be harmonious; 10) vowing not to slander the three jewels (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha).

I ask Barry if any of the students with whom he works in Bisbee have taken the Precepts.

“Yeah. When I came here, of course, they never had a teacher or formal affiliation, so it’s taken a while to migrate the community to the Kwan Um School tradition. Now we have . . .” he pauses to reflect a moment “. . . seven or eight people who have taken the first Five Precepts, and then three long-time practitioners in the Kwan Um School who are part of our community who have taken the Ten Precepts. We call these folks Dharma teachers; not Dharma teachers in the way that you and I might use that term outside the Kwan Um School, but they have taken on the responsibility of leading practice, giving instruction – meditation instruction – and generally being of service to the community. They’re not teachers in the way I’m authorized to be a teacher.”

“What’s the function of all of this?” I ask. “You said, ‘to lead an upright life.’”

“The function is liberation.”

“From?”

“It’s a good question and if you and I were talking less formally and you knew nothing about Buddhism, I would frame the question in terms of the ordinary challenges we have as human being. Problems with our partner; problems with our children; problems with our parents; problems at work. Like that.”

“You’re going to liberate me from all that?”

“No. You’re going to liberate yourself from that,” he says with a laugh. “I’m not going to do anything.”

“And how is this practice going to help me liberate myself from all these problems I’ve got?”

“You have to find that for yourself. And there’s no way of sugar-coating that if somebody’s honest. You’re the only one who can find that out. If I were going to give a nice explanation about it, I would talk about it in terms of awareness and mindfulness and watching the feelings and emotions and perceptions and impulses arise in the mind and making skillful choices about them. That’s a nice explanation. But you’re the only one that can find it. You’re the only one who can find out what it means for yourself.”

One of the issues I’ve been fascinated about as I conduct these interviews is the way what draws people to Zen practice has changed over the decades. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that a majority of those seeking out teachers in the 1960s and ’70s were on a quest for enlightenment. It was in part driven by insights often acquired through psychedelic drug use, but the search was largely for enlightenment, kensho, satori.

Barry admits that these are not words “in favor these days in the Western Buddhist world. I talk about it, but I tend to use the word ‘awakening’ – or ‘awaken’ – rather than ‘enlightenment.’ It’s a word that’s a little less loaded. When most Western people – in my experience – think about ‘enlightenment,’ they’re thinking about pixie-dust falling out of the sky. People and objects glowing with auras. But ‘awakened’ just means being awake. And there are good metaphors that connect with this. One I use is that at night, when you’re sleeping, you have no awareness of your body even though your body’s always present. And even if you’re dreaming about your body, it’s not your actual body; it’s a dream body. But the minute you wake up in the morning, you’re not confused. There’s your body saying, ‘Let’s go pee.’ You get up and you pee. You’re not confused. You’re awake. Your awakened nature – your enlightened nature – is always available, but we don’t know that because we’re dreaming. All we have to do is wake up to what’s always there.

“In Diamond Sutra,the Buddha says in various ways, over and over, that when he got enlightenment he didn’t get anything. If he’d gotten something it wouldn’t have been enlightenment. So each of us already has it. We just need to wake up to it.”

“Regardless,” I persist, “I suspect when people come to the door for the first time, they don’t say ‘I want to be awakened.’”

“Rarely.”

“So, what do they say?”

“Oh, I hardly ever ask that question. If they need instruction, I give them some instruction. And then they practice and either stay or don’t stay. You know, a lot of people don’t come back a second time.”

“Still, you have some sense of what drew them.”

“Yeah, they’ve usually got a life problem. Maybe their spouse is not cooperating or maybe their body is not cooperating. Bisbee is a town of mostly older people, and so we have a lot of loss in our sangha. People are dealing with that. Most members of our community are right up against some of the hardest things in human life. And I think that’s one of the reasons we have a large community in a small town. People have no time to waste. Just this last year we lost our board president at age 85. We lost the person who ran our weeknight practice for over a decade. He was 81. We’re all there right up against it. I’m 77. So, local people are hungry for a community and practice which helps them investigate what their life is actually about.”

“Are you saying one of the things that draws them is a desire for a community?”

He nods. “When people come to the Zen center, they’re joining a community. That’s a very important function of a Zen center, to provide community. To provide support.”

“The traditional Three Treasures,” I suggest.

“Yeah, a cornerstone of the Three Treasures. Exactly. And this last year I’ve found myself more than ever sitting with people who are dying. Or sitting with those whose partners or friends have died. This work is a little beyond my training but, really, all you have to do is show up. It’s just like practice; you just have to show up. That’s the main thing.”

There are young people in the community as well, who he encourages to take part in longer Kwan Um practice retreats at the Providence Zen Center in Rhode Island. These retreats – called “kyol che” – can be up to three months long. “‘Kyol che’ is Korean term that means ‘tight Dharma.’ If people are young and able to engage in that kind of practice, I suggest it. But I don’t encourage somebody who is 75 or 80 years old to do that kind of practice. Not that they can’t – maybe they can – but they have different concerns, most of them.”

“What is it that the people at the Cochise Center look to you for?”

“The first thing is I show up. We only practice twice a week, so I show up twice a week. I’m always there, except for the rare occasions I’m out of town. People depend on the consistency, although less than I might think that they do. To be honest. I think people are quite self-sufficient now in the community.”

“There’s more than one key to the door?”

“There are many keys to the door. Last October I was in Korea for a few weeks, and people came in, turned on the computers, ran practice. Everybody came. Nothing changed. But in some ways, they depend on me to show up. They depend on a model of the practice and the practice life. They ask me to create a safe place for people to practice. Physically safe. Emotionally safe. Spiritually safe. They depend on me to give talks that speak to real human needs and provide some clarity about what it is to be a human being.”

“And what is your hope for the center?

“The center stayed together for fifteen years before I showed up. It will continue after I die. It will grow or shrink. I can’t control that. All I can do is pour my love and commitment into the community as best as I can. Lately I’m investing a lot of energy in the younger practitioners. They’re working on kung-ans; they’re working on personal life issues. It’s not that I’m turning away from the older people at all – there’s a lot to do there as well – but I’m really encouraging the younger people to step forward. And they are.”

Barry believes that it has been a benefit to the center to be formally affiliated with the Kwan Um School.

“When I first moved here, of course, nobody knew about the Kwan Um School. Among the various Western Zen traditions, we’re perhaps less well-known than some. People knew that I practiced in a Korean ancestral tradition, and that was okay with almost everybody. They were willing to adapt the forms.

“When the pandemic started, we closed down physical operations and moved everything to Zoom. And I had the idea that rather than me giving the Dharma talk every Sunday, we would invite teachers from the worldwide Kwan Um School community and have them give talks and answer questions. And it was a real eye-opener to the community in Bisbee to realize that there were all these different people around the world teaching the same bone of Zen but with their own personal way of expressing it. People in Asia, people in Europe, people in America all teaching from the same tradition. This has had a big impact on people. Because the Kwan Um School has an online sangha, local people who practice here also practice via Zoom at Empty Gate Zen Center in Berkeley or with our center in Fairbanks, Alaska, or Boise, Idaho. It’s been a surprise to people. It’s been a surprise to me how much people have taken advantage of that network.

“It’s one of the great gifts of the Kwan Um School. We’re a school; we’re not a loose tradition in the same way that some of the Japanese lineages are. And part of Zen Master Seung Sahn’s gift is that we encourage practitioners to study with many different teachers. We say in the Kwan Um School that Zen Centers have guiding teachers, but students don’t have guiding teachers. Students can study with whoever they want, and we encourage that. As a result people develop a very broad view of the Buddhadharma, as it comes through our lineage. And I think that’s been a great gift to the people here in Bisbee and around the world as well.”

Thank you!

LikeLike