[This is an abridgement of my chapter on Taizan Maezumi in The Third Step East.]

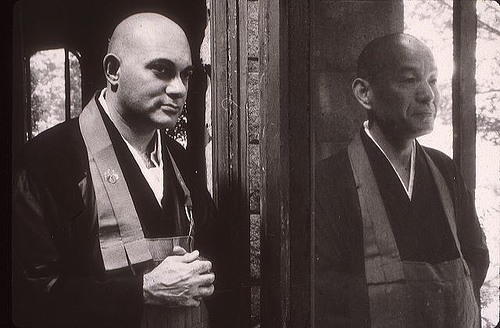

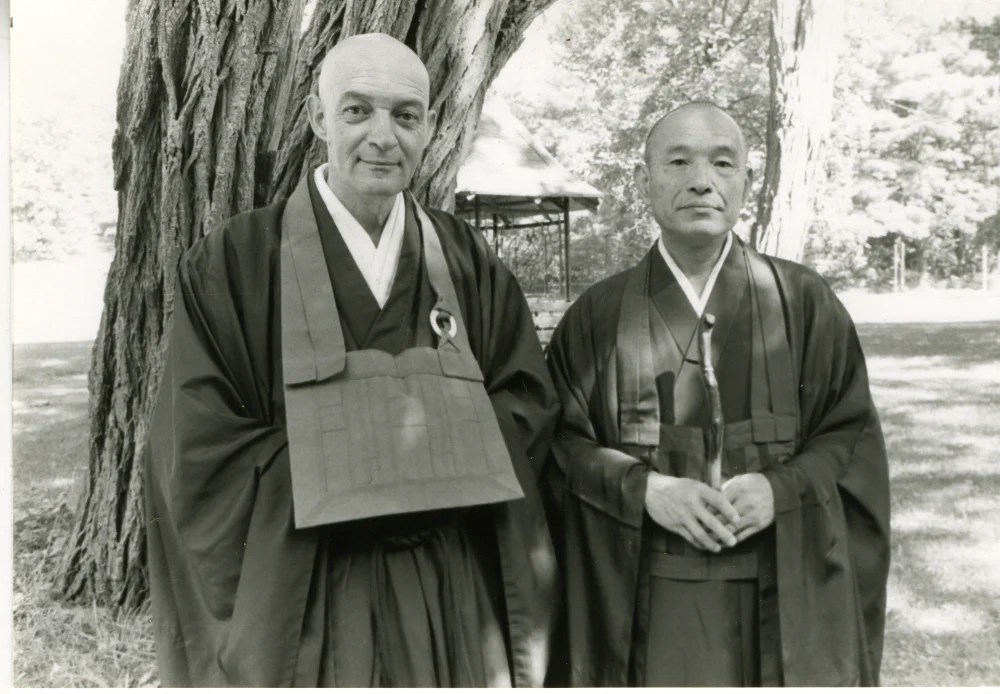

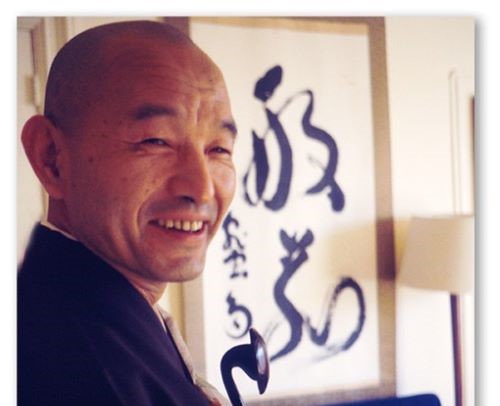

Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi was in the unique position of having teaching authority in three lineages, Soto, Rinzai, and Sanbo Kyodan (later called Sanbo Zen). No one was more qualified to promote Zen in the West.

Born in 1931, he was a teenager during the American occupation of Japan and was intrigued by the soldiers he met. They proved to be very different from the monsters Japanese propagandists had portrayed them to be. They were often friendly and could be surprisingly generous. Maezumi picked up a little English from them; they also introduced him to cigarettes, beer, and swearing.

His father, Hakujun (White Plum) Kuroda, a prominent figure in the Soto hierarchy, was the head of the Soto Supreme Court and a chief advisor at Sojiji, one of the two primary temples in Japan. Four of his sons became Zen priests. By tradition, the eldest would inherit Hakujun’s temple; the other brothers needed to find positions elsewhere.

Because he had a little English, Taizan was sent to the Soto regional headquarters in California when he was 25. Established in 1922, Zenshuji was the first Zen temple in North America. The new priest’s duties were largely ceremonial, conducting funerals, memorial services, and traditional rites. Although he was committed to deepening his own meditation practice, the congregation at Zenshuji had no interest in zazen, which they considered a monastic activity.

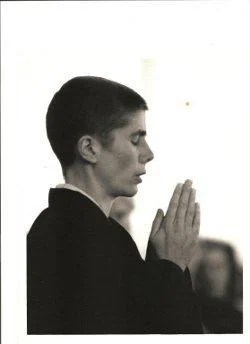

While taking courses at San Francisco State College, Maezumi met Shunryu Suzuki and occasionally attended ceremonies at Sokoji. Suzuki’s Japanese congregation had as little interest in zazen as did Maezumi’s in Los Angeles, but Suzuki had attracted a following of non-Japanese students. Impressed by what he had seen, Maezumi began a weekly zazen program in Los Angeles which also quickly attracted young Western students.

Bernie Glassman met him in 1965. “He was a young monk working in the temple in Little Tokyo in LA,” Bernie told me during our meeting in 2013, “and I started to sit there. But then I left because there was really no English. So I created my own zendo in my garage, and I did it myself. And then I think it was around 1966, I saw there was going to be a workshop led by Yasutani Roshi. So I went to that workshop, and this young monk was the translator. I realized, ‘Wow! He speaks English.’ I recognized he had been in this Temple in Little Tokyo, but now he had his own place. He had just opened it, and I joined him. So from ’66, I was totally with him, going every day, and I became his right-hand man.”

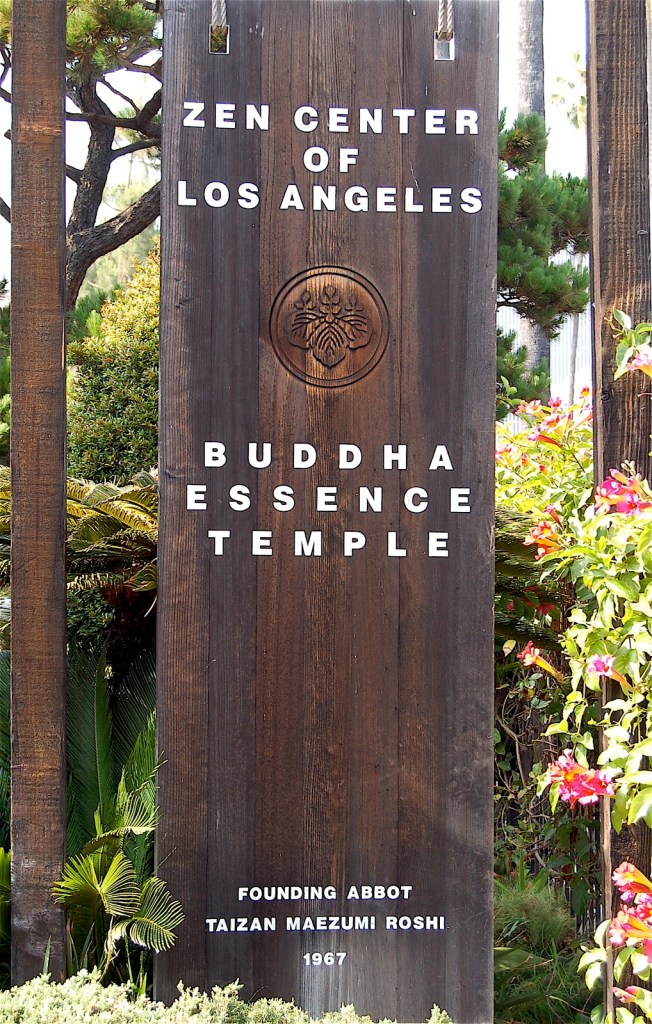

By 1967, the group was so large Maezumi had to find separate quarters for it. He located a house in what had been a Hispanic area of the city but was gradually transitioning to a Korean neighborhood. Here he established the Los Angeles Zendo, later renamed the Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA).

Practice at ZCLA followed orthodox Japanese Soto guidelines augmented by koan study. Maezumi’s insistence on correct ritual behavior, including formal prostrations, was a sticking point for some students, but he knew and expected that the first generation of American-born Zen teachers would make changes to these structures. As Bernie told me, “Over and over he said to me that I should take whatever I can from him—in terms of Zen—and then spit out what I think won’t work in this country. He said, ‘I’m not an American. I’m Japanese. And I can’t present the American Zen.’ He said, ‘You’ve got to do that.’”

Robert Kennedy made the same point. “Maezumi Roshi was very clear that we should make Zen American. We should not imitate the Japanese. And it is not necessary to do so. I think the Japanese can’t really be imitated anyway. They’re a completely unique civilization. A wonderful civilization. But it’s not our job to imitate them. Our job is to find a Zen that is open to American culture, American life. It is not necessary to wear Japanese robes in order to see your own nature. And it’s not helpful finally. You’re just creating something artificial in a practice that imitates the Japanese. Now some Zen people will disagree with this. But I would just say that Maezumi was clear that we were to do what he could not do, which was to make Zen American. And as soon as Maezumi died, Glassman, for example, said he became himself, not only Maezumi’s student but his own man as an American interested in social issues in a way that, perhaps, Maezumi was not.”

Before these changes were made, however, Maezumi wanted to ensure that his heirs were grounded in the traditional forms.

In spite of its formality, ZCLA went through a period of rapid growth during the 1970s. The communal atmosphere of the Center proved to be a draw; unexpected numbers of young people were attracted by the idea of living in a community focused on a formal spiritual practice. When John (Daido) and Joan Loori (now Joan Derrick) first came to the center, there were 27 residents. Soon the number of residents was approaching 200, and space needed to be found to accommodate people.

In addition to the hippies then swarming to California in search of spiritual guidance, ZCLA also attracted a number of well-educated professionals. Glassman was an aeronautical engineer; Jan Chozen Bays (then Jan Soulé) was a pediatrician; Loori, a professional photographer; Gerry Shishin Wick was an atomic physicist and oceanographer.

Two hundred people living together inevitably presented challenges. There were families with young children for whom childcare needed to be provided. Parents were torn between family responsibilities and the desire to commit as much time as possible to their practice. On top of which most also had to earn a living.

The Center purchased buildings and apartment complexes on their block as they became available; these were prudent investments but required initial funding. Glassman proved to be a natural entrepreneur, and he established a number of businesses to help meet rising expenses. ZCLA ran landscaping, carpentry, house-painting, and even plumbing operations. Partly to establish goodwill with the surrounding community, Bernie encouraged Chozen to open a medical clinic. Services at the clinic expanded as new students came to the Center bringing with them expertise in alternative therapies such as chiropractic, acupuncture, and homeopathy. Originally intended to serve the neighborhood, the clinic began to draw clients from other parts of the city as well. “We had a combination of Western and alternative medicine which was very unique at that time,” she explained to me. “And so people from wealthy areas, Hollywood and Rodeo Drive, would come to the clinic. So we had this weird waiting room where we had Sikhs and people with Gucci bags and very, very poor Hispanic patients, all together in the same waiting room.”

Satellite zendos were established, and a network of practice centers – which would eventually be called the White Plum Sangha – was envisioned. Charlotte Joko Beck opened a Zendo in San Diego. Glassman founded the Zen Community of New York, and Daido Loori established Zen Mountain Monastery in the Catskill Mountains. Each of the new centers was registered with Japanese authorities.

By 1982, ZCLA and its associated centers were one of the most vibrant Zen programs in America.

Throughout the period of expansion, Maezumi’s students were aware of his fondness for alcohol. To some extent, they enabled his drinking because, when tipsy, he became quick witted and acted and spoke like the Zen masters in the stories that D. T. Suzuki, Alan Watts, and others had made popular.

Chozen recalls: “He was funny when he got drunk, which was unfortunate. People would encourage him to get drunk because another side came out. The Japanese don’t usually tell you the truth because they don’t want people to lose face. It’s a different culture. For example, if Maezumi Roshi had something he wanted to tell me that was difficult, he would tell one of my Dharma brothers, and then they were expected—it took a long time to learn this—to come tell me, so I wouldn’t lose face by being confronted by Maezumi Roshi directly. So he would tell Genpo [Dennis Merzel] or Tetsugen [Glassman] something he didn’t like that I was doing, and then they would tell me. And vice versa. He would tell me something that I had to tell them. That’s the way it’s done in Japan. But when he was drunk, he would be very honest. In Japan, it’s looked at very differently; if you’re drunk, you can be forthright, and it’s all forgiven the next day. So you could say something rude to your boss and the next morning it would be totally forgiven. So, when he was drinking, he would tell you what he thought of you. And you wanted to hear that, and you didn’t want to hear that. But the temptation was very strong to hear that. So people would drink with him, or sit with him when he was drinking, just to find that out.”

At first, Maezumi’s drinking was not seen as particularly problematic. He didn’t allow it, for example, to interfere with his commitment to practice. On the other hand, when he had been drinking, he would at times flirt with female students, even during dokusan. Joan Derrick was married to one of his senior students and their son had recently been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor, so she was both surprised and angry when she realized what Maezumi was doing.

“I went into dokusan, and Maezumi was particularly loving, and so sweet, and he tilted his head, and he was smiling at me, no matter what I was presenting to him. He was flirting with me! And I said, ‘Don’t be flirting with me! I don’t want to know anything about that!’ And that was the end of that. He straightened his head up, and he never did that again.”

In 1983, however, when it became obvious that Maezumi had done more than flirt with other women, his wife left the community taking their younger children with her. During my conversation with Joan Derrick, she reflected, “There was an amazing amount of drinking, and it was always started by the roshi. And all of us just jumped right in. We figured, you’re sitting hard in sesshin, and it’s a tortuous week, and then let’s party when it’s over. So there was a lot of craziness going on at that place, and I’m not really sure why. I think we American women are extremely selfish and very dominating, and we want what we want. Not just women; men too. But, for sure, the womanizing thing had two folds to it. There were women who propositioned him as much as he took advantage.”

Although her own affair with Maezumi contributed to the break-up of her marriage, Chozen Bays tells me that the sexual aspect of their relationship was minor.

“We had this very strange mix of hippie-commune and monastery. And not a terribly clear understanding of our own psychology. I think there was some spiritual-by-passing that happens in Zen often. So what happened with me was that I fell in love with Roshi. But in retrospect, after doing a lot of study and reading, I would say I fell in love with the Dharma through Roshi, as embodied by Roshi. In a way, what you’re falling in love with isn’t the Dharma in that person but your own potential. So, it’s like a mirror. You’re falling in love with your own potential to become what this person embodies for you, or your own version of it. And then you want to become intimate with it. More and more intimate with it. But because our human understanding of intimacy is so limited and involves sexuality, then you think, ‘Oh, this must be sexual. That’s a way to become more intimate.’”

Maezumi made a full public confession after his wife left and admitted that the lack of judgment he had demonstrated in the affairs was due, at least in part, to his drinking. He acknowledged that he was an alcoholic and voluntarily entered the Betty Ford Rehabilitation Clinic. His students were stunned. Outside counselors were called in, and the community confronted the fact that they had, to a large degree, been complicit in enabling Maezumi’s behavior.

While Maezumi underwent treatment, much of what he had accomplished in Los Angeles began to unravel. Students reacted in a number of ways. Some insisted that, at least as far as the sexual affairs were concerned, his private life should be no one else’s business. Some even tried to argue that the behavior of enlightened individuals should not be judged by ordinary standards. Others, however, questioned his credibility as a teacher, and many left the center.

In the midst of the trauma, a film crew, which had earlier arranged to do a documentary about the center, arrived. The instinct of many of the members was to cancel the shoot, but Maezumi insisted that the filmmakers be allowed to stay and complete the project. He agreed to be interviewed and, in the released film, frankly discussed his alcoholism without excuse, accepting full responsibility for his actions. He lamented behavior that he now characterized as “outrageous” and “scandalous,” admitting it had harmed his family, his reputation, and, possibly, the Dharma as a whole.

Shishin Wick was the chief administrator at ZCLA at this time. “When I first got there—you know—it was pretty exciting spending time with him. He’d always invite me to come to his apartment. You said Chozen described it as a hippie commune, but I was one of the few people that came there who was mature. A Ph. D. university professor.” He laughs softly. “But I was still a hippie. Or at least had very liberal thoughts and attitudes. But he’d invite me to drink with him. And I remember one time it triggered something, and I just started crying; something that was a great release for me. And he said, ‘That’s what I’ve been waiting for.’ So, we used to think—and I heard a lot of people say it—that when he was drunk was when he was ruthlessly honest as a teacher. But then I saw him doing things when he was drunk that I thought were pretty immature, and I just decided I no longer needed to be around that. Even though I lived there and was close to him, I decided when he was drinking I just didn’t want to be around him. He was an alcoholic, but so were most of the Japanese teachers that came to this country. I think that in Japan the culture is so tightly defined—your role in the culture is so tightly defined—that you can only let loose when you’re drunk, and they excuse that. You know? It’s a cultural thing. I read something that Aitken Roshi wrote that said, ‘In our country, we would say someone was an alcoholic. In Japan, they would say, “He likes sake.”’

“But we did intervene, and he went to the Betty Ford Clinic. I don’t think it had a lot of impact on him except for a couple of things. One: he never drank in public after that. And, two, he was very contrite about the damage he caused to the sangha and particularly about his relationship with Chozen, who was a Dharma successor. He just felt it caused problems.”

The community fractured. A number of members left. Without their contributions, the financial situation deteriorated, and Shishin had to oversee the selloff of several properties.

“Why did I stay? Because I’m very loyal. And I learned in his dokusan room, and he was a real master. And that’s what I came to do, to learn the Dharma. If I wanted to learn to play the violin, I’d find the best master I could to teach me to play the violin. Now, if he was mean to his children, that may or may not affect whether I continued to study the violin. But he did—ostensibly—modify his behavior. And there weren’t as many issues with women. And I don’t lightly abandon people. If it were my father, I wouldn’t abandon him, and he was my spiritual father. So I stayed there and helped right the ship, and I was very frank with him. If I thought he was doing something inappropriate, I’d tell him. And he was responsive. I got in a big fight with him one time, and he actually apologized.”

Although he was no longer seen drinking at ZCLA, some people suspected he might have continued to do so privately. “I think he drank at home, with his wife,” Pat Enkyo O’Hara tells me. “Because what he did was he moved. They bought a place near the Mountain Center, and he would go home for the weekend sometimes. And it was none of our business what he did at home.”

He also allowed himself to relax and drink socially while in Japan. In 1995, he travelled there to visit family members. He was with his brothers at the family temple in Otawara on May 15. He intended to spend the following day with another brother in Tokyo, and, although it was late and they had been drinking heavily, Maezumi took the train into the city. He fell asleep during the trip and missed his stop, so it was even later than he had planned when he finally arrived at his brother’s house. He told the brother that he was going to take a bath in the large traditional Japanese tub and then retire; there was no need to wait up for him.

The next morning, when the brother got up, he discovered Maezumi had drowned in the tub. In order to protect Maezumi’s reputation in America, the family told the students at ZCLA that their teacher had succumbed to a heart attack during his sleep. It was only two years later, when staff at ZCLA requested a copy of his death certificate for insurance purposes, that the actual details of his death were revealed.

Maezumi’s sexual indiscretions, his drinking, and even the circumstances surrounding his death, raised questions and concerns among his students as well as in the wider community of both Buddhists and non-Buddhists in America. Similar problems were arising elsewhere, especially in San Francisco where Shunryu Suzuki’s only heir was compelled to resign his position as abbot because of his lifestyle, including his relationships with multiple women in the sangha.

Unlike most of these others, Maezumi accepted responsibility for his failings and didn’t try to excuse his behavior. Still, the circumstances and the way in which students responded to them revealed a significant cultural chasm not only between Japanese and North American values but also between the fundamental metaphysical premises underlying the Judaeo-Christian worldview and that of Buddhism.

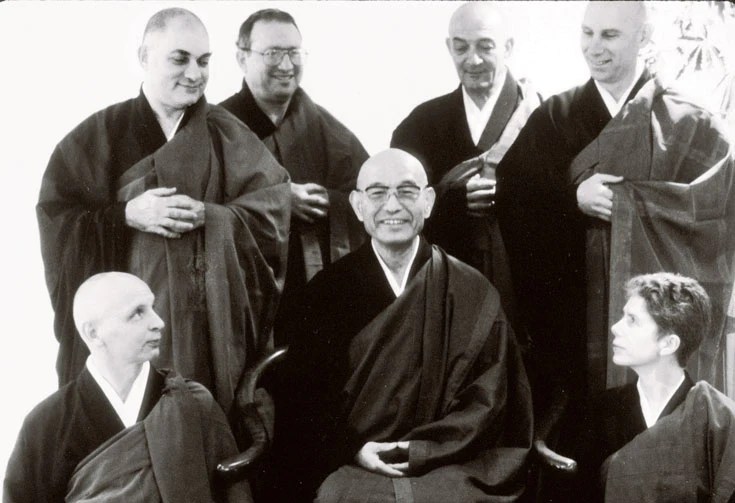

Despite everything else, Taizan Maezumi had been dedicated to ensuring that the Zen tradition would continue in America after the initial Japanese teachers gave way to a new generation of American-born Zen masters. He saw himself as a steppingstone in a process by which Zen would become fully Americanized. The realization of the White Plum Sangha and his one dozen transmitted heirs were measures of his success. In addition to the centers established by Glassman and Loori, Chozen Bays established the Zen Community of Oregon, Genpo Merzel established the Kanzeon Zen Center in Salt Lake City, Shishin Wick, the Great Mountain Zen Center outside Denver, and Tesshin Sanderson, the Centro Zen de México in Mexico City. Other centers were established in New Zealand, Great Britain, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Germany, and Poland. Maezumi also founded the Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism and Human Values at the University of Hawaii in order to ensure an appropriate academic foundation for Zen studies. It is a legacy unmatched in North American Zen.

The Third Step East: 165-82; 9, 119, 161, 220, 231, 232

The Story of Zen: 5, 78, 269-76, 284, 286, 302, 304, 307-08, 309, 320-23, 336, 337, 343-49, 350, 353, 354, 356, 363, 414, 424

20 thoughts on “Taizan Maezumi”