Abridged from Catholicism and Zen –

Combining Zen practice and Catholicism is based in “the recognition in experience of a resonance between the two traditions. Many Catholics remark, after their first Zen experience, that it is what they have always been seeking.” So wrote the first Catholic priest born in America to receive Dharma transmission. Patrick (always known as Pat) Hawk went on to note that what such people are seeking is “not a thing, nor even understanding, but rather a living awareness of no separation from” that Ultimate Reality that may be variously understood by different religious traditions but that is innate in everyone. This “direct, non-mediated experience has been the central focus of Zen in Buddhism and contemplation in Christianity;” therefore, the technique of Zen is able to offer a way of practice for those seeking to pursue the contemplative tradition in Christian prayer.

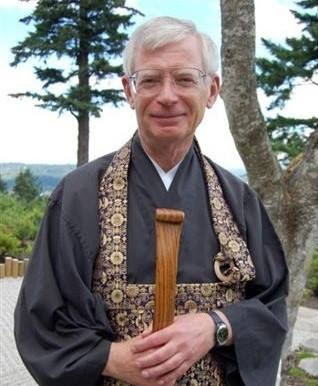

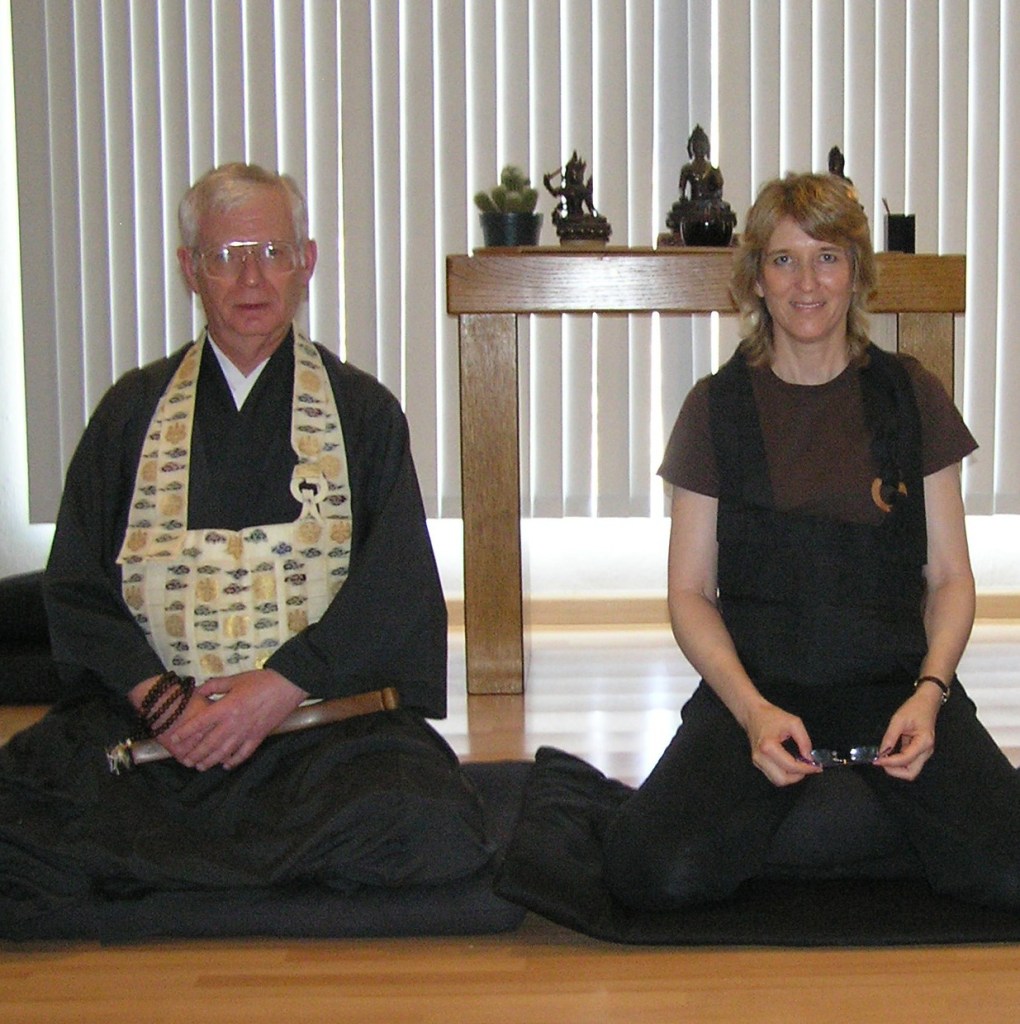

Pat Hawk was a member of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer or Redemptorists. He died in 2012, before I had a chance to interview him, and much of the information I have about him comes from his biographer[1] and student, Helen Amerongen. “He grew up in Granite City, Illinois,” she tells me, “across the river from St. Louis, one of two children. He was the first child, and then he had a sister seven years later.”

“Was it a devout family?”

“Yes. Very Catholic. Very standard Catholic family. Happy to have a child become a priest.”

Pat claimed that he knew he wanted to be a priest by the time he was seven years old.

In the 1950s, it was common for young boys to begin training for the priesthood while still in high school; he was 13 when he entered St. Joseph’s College, the Redemptorist minor seminary in a suburb of St. Louis.

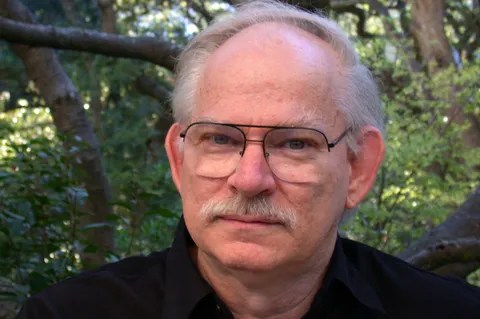

Greg Mayers entered St. Joseph’s two years later, in 1958, at the age of 12.

“One of the requirements in seminary, everybody had to play sports. I wasn’t very good at sports, and it was baseball. And they organized the teams as majors, minors, and rookies. So I was in the rookies, and Pat Hawk was in the rookies. And we were all out on the diamond, and Pat Hawk was the team captain. And I was very embarrassed, ’cause I didn’t know how to play. But I was smart enough to know that nobody ever hit a ball to right field. So I decided that was what I wanted, to play right field. So Pat Hawk comes out, and all these kids gather screaming about what position they wanted, and I got close enough to him to say, ‘I want right field.’ And he looked at me with the withering eyes of a fourteen-year-old and said, ‘That’s my position.’ That was my first encounter with Pat Hawk.”

“What was he like as a student?”

“Quiet. He was a very quiet person. And private.”

“Introverted?”

“Introverted, yeah. Very much so.”

As is common with introverted persons, Hawk was reflective, and, Helen tells me, when he was in the major seminary he had a crisis of faith.

“In what way?” I ask.

“Losing his faith in God. He never doubted that he should be in the seminary or that he would be a priest. Even in spite of the crisis of faith, he did not doubt that this was where he wanted to be.”

He was only in his 20s at the time, and the Second Vatican Council was taking place, which allowed seminarians greater freedom in their reading than earlier generations had had. “He was a prodigious reader,” Helen notes. He was also the assistant to the seminary’s librarian and saw new books as they arrived. One by Jean-Marie Déchanet was entitled Christian Yoga. Following the instructions provided in the book, he began a private meditation practice.

Greg and Pat’s training overlapped during the four years of theological study in the major seminary prior to ordination. “We had an extremely competent Dean of Men who had started counselling and group counselling sessions with the students. And I met Pat in the group counselling sessions, and we kind of had a bonding there. Then after seminary, those of us who were in the group counselling thing would meet every summer to develop and sharpen our skills at counselling.”

Greg and Pat fell out of touch for a while, although Greg knew that Pat had developed an interest in Asian spirituality. In addition to Dechanet’s book, Pat read the Zen popularizer, Alan Watts – whom he recommended to Greg – as well as Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, which he admired. So when the Palisades Retreat Center, where Greg was on staff, sponsored a Zen retreat for Christians facilitated by Robert Aitken, he informed Pat of it.

The retreat came about largely because of Aitken’s involvement with the peace movement, which had brought him into contact with members of the Catholic Worker Movement. Helen explains that in 1977 he, “was participating in what came to be called the Bangor Summer at the Trident Missile Base in Bangor, Washington. There were all these demonstrations, and the Catholic Workers of Seattle were major movers in them. And some of those Catholic Workers and some other people – who were spiritual advisees of some of the Trappists at Our Lady of Guadalupe Abbey in Lafayette, Oregon – knew each other. So one of the Catholic Workers took Robert Aitken down to meet Bernard McVeigh, the abbot of Guadalupe Abbey, and together they cooked up this idea of offering a Zen retreat ‘for Christians and other travellers.’ And that first retreat was at Palisades. Greg Mayers was a spiritual advisee of Bernard McVeigh. So although he was not in on the initial conversation, Greg heard about it from Abbott Bernard and invited them to use Palisades.”

“So after Bernard McVeigh said Bob Aitken had agreed to do sesshin for Christians,” Greg tells me, “I thought, ‘Oh, Pat Hawk practices Zen! He would be interested in this.’ So I called him up and told him about it and said, ‘Why don’t you come out and attend?’” It wasn’t until later that Greg learned this would be Pat’s first formal Zen retreat.

“He said he took to it like a duck to water,” Helen tells me. “I said to him, ‘Did you find it awkward?’ You know, all the ritual and everything. It was not actually the full-blown ritual of a Zen sesshin. They did have some Zen ritual, but they modified and Christianized a lot of it. He immediately formed a relationship with Aitken. Aitken told me that he saw, right from the beginning, that Pat should be a teacher. ”

Greg informs me that shortly after that retreat, Pat entered “a rehabilitation center for alcoholism for priests. After that, he came out to the retreat center I was working at and stayed with us for about six months.”

“He was a patient?”

Greg nods his head. “He was an alcoholic,” he says gently.

“When did that start?”

“I don’t remember. He was teaching at the seminary – the minor seminary – and the other professors there did an intervention.”

“Did he shake it? Did he acquire sobriety?”

“For a while, and then he had to go again. Alcoholics don’t . . . There are often a lot of slips in the disease.”

The Redemptorists at Palisades hosted several sesshin conducted by Aitken, but eventually Aitken came to feel that the tone of these was growing too Christian for his comfort. “People were bringing him things that he couldn’t handle,” Helen explains. “Their experiences often were within a Christian framework. He had a Dharma brother, Willigis Jäger in Germany, who was also a Yamada Koun student, and he recommended Willigis to the group, and they invited him to come. So Willigis Jäger took over leading those retreats. Pat did one or two retreats with Willigis, and Willigis invited him to come to Germany. Pat got approved to do a year’s sabbatical in Germany, so he did that from August ’84 to August ’85.”

After the year with Willigis, Pat returned to the US and completed his Zen training with Aitken, who gave him transmission in May 1989.

By 1986, Pat was offering Christian contemplative retreats modeled after those conducted by Jäger in Germany. The first of these, co-facilitated by Greg, took place at the Bishop DeFalco Retreat Center in Amarillo, Texas. They were not Zen retreats, but the format had clearly been influenced by Zen.

Although Pat was given permission to teach Zen in August 1988, he did not lead sesshin until after his transmission in 1989 when Jäger – who found travel between Germany and Washington State taxing – asked him to take over the Northwest group. A little later, Greg was also authorized to teach by Willigis, and he and Pat began leading sesshin in the Northwest and at the DeFalco Center where they were then both located.

“The Bishop of Amarillo at the time, Leroy Matthiesen, was very supportive,” Helen tells me. “But then he retired, and Bishop John Yanta took over, and he dismissed the Redemptorists.” Yanta was fundamentally opposed to the idea of the Zen and contemplation retreats. He is reported to have once said that “Cowboys don’t need contemplation.”

Greg returned to Palisades. Pat moved to Picture Rocks Retreat Center in Tucson, Arizona – now known as the Redemptorist Renewal Center – which would be his home until his final illness.

Like many of Pat’s students, Steve Slottow was not Catholic. He had been drawn to Zen by Philip Kapleau’s The Three Pillars of Zen. While still a very young man, he moved from Illinois to Rochester, New York, in order to practice at Kapleau’s center, although he didn’t become a resident.

Kapleau had sought to duplicate the intense Japanese training style of Sogaku Harada Roshi. “People screaming Mu in chorus and very, very heavy use of the kyosaku. So there was a lot of bushido/samurai spirit in Rochester at that time. And everyone was very young, of course, all the students. It was too bushido-ish for me.”

Steve played in an Old Time music band in the Rochester area for a while and then, when the group broke up, went to the City University of New York to do graduate work in music theory. “I was looking for places to practice. I bounced around, and I eventually found out that Robert Aitken’s heir, Nelson Foster, had a small group in New Haven, and he would go a couple of times a year and give short sesshin there. It was called the East Rock Sangha. And I had been attracted to the Diamond Sangha and to Robert Aitken for a long time because it seemed much less bushido-samurai than Rochester.”

Steve found Foster helpful. “He was very nice; he was very impressive.” But he only visited New Haven periodically. At the time, Steve was also engaged in an early internet chat-line dedicated to Zen practice. One of the other members mentioned attending a sesshin with Pat Hawk. “I knew that Pat was a Dharma brother of Nelson Foster. But Nelson wasn’t around that much. And Pat sounded interesting because Pat was . . .” He pauses to reflect, then says, “He was a curmudgeon. He was very quiet. He wasn’t exactly reclusive because the order he belonged to wasn’t an eremitic order, but he was as much of a recluse as he could be. He was extremely plain and down to earth. He was very understated. There was no charisma. You see? I distrusted charisma. So somehow he sounded like my type of guy. Kinda grouchy. Very quiet. Didn’t care about impressing people. So I went down to Tucson, and I did a sesshin with Pat.

“He liked to meet prospective students in a very informal setting before the sesshin started. So we just went to a little table outside. He was a very plain guy dressed in old clothes. Totally unassuming. He didn’t talk very much, just asked a few questions about where I was from and what my interests were and why I was there. He was this plain, quiet, dry – extremely dry – guy. He didn’t seem particularly enthusiastic. I was totally charmed. He was just this kind of desert rat. He was living in Tucson, but, of course, he wasn’t from there. But he sort of fit into the landscape, although I’m not sure he even liked it. There were no frills, no airs. Nothing to stand out. I told him about my Rochester Zen Center experience and said that I felt a little burned-out with Rochester. And he replied, ‘Well, we’re used to dealing with Rochester burnouts here.’”

I mention to Helen that another of Pat’s students had described him as a curmudgeon.

“Yeah. He had that side. He had a curmudgeonly side, for sure. Although that’s misleading too, because he was mostly a gentle soul. And he had a dry wit that could be gut-splittingly funny.”

She tells a story to help give me an impression of him.

“A student of Pat’s was working with him in Santa Fe, and there was only Zen sesshin at that center. Then this person moved to the Northwest, where for a long time Pat’s retreats were all Christian contemplative. He eventually offered Zen retreats up there, too, but for years it was just Christian contemplative. So this person was travelling from the Northwest to either Tucson or Santa Fe to do Zen retreats, and it was expensive. So Pat said, ‘You know, you can come to the contemplative retreats.’ But, as with many people, this student wasn’t interested in getting involved with anything Christian. And Pat said, ‘It’s the same silence. You can just sit.’ So the man went to the contemplative retreat. And first time going into interviews, there’s Pat sitting in a chair instead of on a cushion on the floor – just one of the small differences in format between Zen and Contemplative retreats. And the man says, ‘What’s with the chair?’ And Pat says, ‘In Christianity, we have a merciful God.’”

The forms of the Christian retreats and the sesshin were distinct. Although Zen students were welcome to participate in the Christian retreats – and vice versa – there were no overt Buddhist elements in them, nor were there Christian elements in the sesshin.

“He kept them entirely separate,” Steve tells me. “I compare Pat’s approach with Ruben Habito’s approach. Habito was sort of after a kind of fusion. Pat was after a kind of apartheid where the Christian stuff was quite different from the Zen stuff. So the Zen sesshin were Zen sesshin. The Christian stuff, there were Christian figures on the altar; instead of sutra-chanting there were readings from the Psalms. There was the mass with the Eucharist, which was optional. People who were there primarily for the Zen aspect could simply continue working on their Zen practice during these and have dokusan. In the Contemplative Intensive Retreats, the CIRs, it wasn’t called dokusan; it was called ‘interview,’ I think.”

“But it was a meditation retreat?”

“It was basically a sesshin format, but the schedule was easier. As Pat said, ‘We change the idols on the altar.’ And some of the people who went to them didn’t follow the forms very precisely. The CIRs had forms and rules. It’s just that some of the participants – the ones, I think, who were not very interested in the Zen side – were not very invested in following them precisely.”

“Mostly they were both silent sitting facing the wall,” Helen tells me. “But the rituals were different. The Zen retreat started a little earlier in the morning. The bells were pretty much the same, regulating standing and sitting and so on. The first thing in the morning with the Zen retreat there’s a thing called kentan where the teacher walks around the room; it’s a formal inspection of the zendo that’s not in the contemplative retreat. In the CIR, first thing in the morning you chant ‘shalom’ for five minutes. So there’s a little difference there. The schedule for dokusan – the one-on-one meetings are called ‘interviews’ in the CIR – the schedules were a little bit different. There were a few things like that. In the CIR, there was ‘conference,’ which was the talk in the morning after breakfast. On the Zen side, there was teisho, and that was after lunch. The conference topic could focus on the Desert Fathers, a story from the Desert Fathers, or perhaps the Christian mystics, Eckhart, people like that. On the Zen side, most teisho began with a koan; he’d read the case and go on from there.”

I ask Steve if he had a sense of how well Hawk was accepted by other members of the Redemptorist Congregation. “I don’t know about the whole congregation, but in the part that was at Picture Rocks Retreat Center, he was very accepted. He basically ran a whole program of Zen and contemplative retreats at the center called the Pathless Path. And the order had no problem with this whatsoever. He was well-regarded, well-respected.”

“The Redemptorists were supportive,” Helen tells me. “And two of his Redemptorist confreres, one being Greg, went to his transmission ceremony in Hawaii. The other was Bob Curry, who at the time was Pat’s superior. As far as I know, nobody opposed it on the Redemptorist side. Were there others who were kind of suspicious of this Zen thing? Yes, I think so.”

The broader church hierarchy was not always sanguine about Zen. 1989, the year of Pat’s transmission ceremony, was also the year that then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger – later Pope Benedict XVI – spoke out about what he felt were the dangers attendant upon Catholics taking up Eastern meditative practices.

“Pat would allude to this sometimes,” Steve says. “He was reluctant to have anything recorded. He only published two articles in rather obscure journals because he wanted to keep a very low profile. He was very straightforward about that. He didn’t want to draw a lot of attention to himself.”

I ask Helen what made Pat an effective Zen teacher.

“I felt totally received by him. That was perhaps his greatest gift. Also, the very fact that he had his own struggles, his own demons, and that he had faced them, gave him a kind of trustworthiness. And he had a nose for guiding people. He had a good instinct for giving people what they needed at a given moment to move them along.”

“I stayed with him till he died,” Stephen tells me. “When I began working with Pat he had already been diagnosed with prostate cancer, and eventually the schedule of his sesshin was lightened – you got up later, there were fewer rounds – mainly to accommodate Pat. It was hard for him. And eventually he sent a very, very short note to his fellow teachers in the Diamond Sangha, to his students as well, saying, ‘I’ve been told I only have so long to live. I have some things to take care of. I’m retiring as of now. No more sesshin, no more dokusan, no more Skype. We’ll figure out what to do. But that’s it.’ And he stopped teaching at that point. And then he got worse and worse. I talked with him a couple of days before he died. I had a short phone conversation with him. And then we got some daily bulletins from the people who were taking care of him. Then he died. I don’t know how long it was after he retired. Maybe a month or two. It wasn’t a long time.”

Helen tells me: “He died in Liguori, Missouri, which is where the Redemptorists have a healthcare facility including hospice care. He was flown out there in mid-April 2012, and he died May 8, 2012. So he was there for about three weeks.”

I ask Greg Mayers if he worked with any of Pat’s students after his death.

“Very briefly. I think they were hoping somehow to revive the program that he was involved in in Tucson, and I was invited to give sesshin. But there were very few students that showed up. You can’t really step in. I tried to tell them that. ‘Look, this stuff gets really personal with the teacher. Nobody else can come in and step in and take that person’s place.’”

Steve tells me: “When Pat announced his retirement, I knew I wanted to work with another teacher, but I cast around for a while. I went to some all day sits with Ruben Habito, who’s nearby. His center is in Dallas, very close to Denton. And I went to a sesshin with Leonard Marcel, Pat’s Dharma heir.”

Pat Hawk viewed his Catholicism and his Zen practice as complimentary. What tension there was between them he compared “with the tension of having two arms. With practice one becomes ambidextrous. It is just a matter of doing. Let not your right hand know what your left hand is doing and it is done.”

🤩

LikeLiked by 1 person