A conversation with Tim Ryuko Langdell –

Tim Ryuko Langdell is the guiding teacher at Still Center Zen in Pasadena. He contacted me after I had written a post about the Japanese teachers who first brought Zen practice to North America. I had neglected, he informed me, to include Soyu Matsuoka. In fact, I was unfamiliar with Matsuoka.

Although Tim is British by birth, he began coming to the United States regularly in 1973 – at the age of 20 – to practice at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. He’s an easy and fluid speaker who can run with the answer to a question faster than I, at times, can keep up.

“I instantly felt a connection to the Zen Center of Los Angeles. But one of the feelings I had about being there for many, many years, is – and this isn’t a criticism; it’s just a personal preference – that rather being Zen for an American audience it’s trying to be Japanese Zen here in America. And it’s not alone in that. Most of the Zen centers I know around America are trying to bring the Japanese experience to American people. So they will shave their heads, they will wear the full robes. They will do chants in Sino-Japanese. And it all seems very . . . To me, it feels like, ‘Well, that’s nice, but we’re not Japanese.’ What struck me upon learning about Soyu Matsuoka is that not only is he the first Soto priest to bring Zen to the west, but rather than set up a Zen center styled on the monastic constructs of the Japanese Zen temples, he focuses on talking to his audiences as regular North Americans. Therefore, his followers can have robes – it’s not that they can’t wear robes or don’t wear robes, some of them do – they have rakusus, but the level of formality is pretty light. It’s definitely Soto-shu lite. He never formed a formal Zen Center in the sense of ZCLA or the San Francisco Zen Center. The Zen Centers he formed are usually in peoples’ houses. So they took over homes, or they rented a house to become a Zen Center. I think that’s one reason he isn’t as well-known. Because it’s not, ‘Here’s the Zen Center called something with -ji on the end that was founded by Matsuoka Roshi.’ Which is why we’ve heard of Maezumi, which is why we’ve heard of Suzuki or Sasaki or Shimano; so he slipped through the cracks in the histories for that reason.

“He styles his Zen as Zen for the average person. And he has a very simple structure compared to, for example, Maezumi’s White Plum structure which is partly Soto, partly Rinzai. They have several different layers. You can take all Sixteen Precepts. You can become a novice priest or a monk. You can work on the teacher path. Or you can go up the priest line which involves such things as Dharma Holder, Head Priest, all the way up to fully ordained priest, all the way up to being fully transmitted. Inka shomei. Many, many stages. Matsuoka simplified it to basically three or four. Take the Precepts. If you feel called to something more, become ordained as a novice priest, then as a priest, and very rarely also have people as roshis. So there only have been something like six roshis in his tradition of which I am one, where there would be many of them in all the other traditions I’m aware of. He wanted to flatten the hierarchy, to keep a more human level, more aimed at the average person. And the impression I get from his teachings is that although he did ordain people, they didn’t suddenly become the important people in the room. I don’t mean that to sound critical. I appreciate that it could do because I have been in situations where you can have it very clearly indicated to you what the hierarchy in the room is from the roshi all the way down, depending on the robes you are wearing. He tried to start it in a much more egalitarian way.

“His Dharma talks quite frankly stunned me when I first read them. He was as likely to go the local Police Confederation and talk to the local Police Academy or local firefighters or give a talk on Zen at the local high school as he was to invite people into one of his Zen Centers and have a formal Dharma talk in the way that you might be more familiar with Maezumi or Suzuki. So all of this, to me, adds up to not only the first attempt to bring Zen practice to North America by a Soto priest that I’m aware of, but it’s also the first attempt to bring a more truly American Zen practice rather than a transferred or transposed Japanese practice into a North American setting.

“The core of Matsuoka’s teaching was Zen in everyday life. Not Zen on a cushion in a zendo in a quiet time once a week, once a day at home or whatever, but moment to moment to moment Zen practice. And he taught that over and over again. Something that I’ve been teaching for many years now, and I’ve got some strange looks because it’s like, ‘No. Soto Zen is shikantaza; it’s sitting on a cushion, facing a wall, and you’ll become enlightened.’ Our approach for many years has been, ‘Maybe. But except possibly Siddhartha Gautama himself, we don’t have even one story of a person becoming enlightened on the cushion.’ It’s just an historical fact. If we believe the writings, it’s never happened. But we do believe very much in zazen in a very real sense. Yes, it means ‘sitting meditation,’ but it can also mean walking meditation; it can also mean moment to moment meditation as you drive your car, work in your office at work, do the dishes, cook the meal, do the gardening. Whatever it is. That moment to moment, that can be zazen.”

I ask if we can back up a bit and get some biographical data.

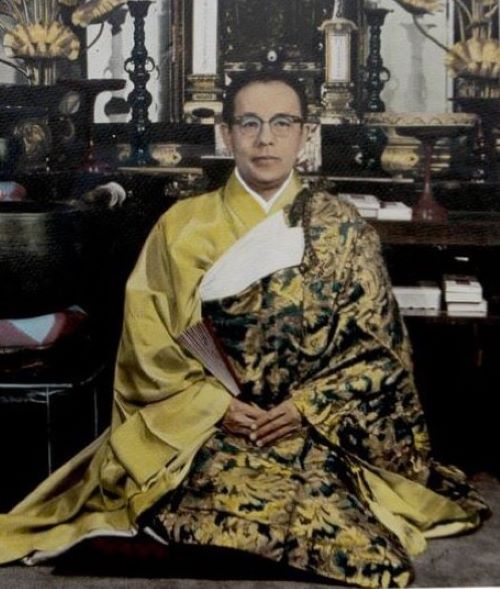

“Okay a quick overview of his early life. He’s born near Hiroshima in 1912. He attends Soto-shu’s Komozawa University in Tokyo and graduates with a Bachelor’s degree. He then trains at Soji-ji Monastery which, of course, along with Eihei-ji, is one of the two main Soto-shu monasteries. And after several years at Soji-ji he’s given the assignment to establish a temple in the far north of Japan on Karafuto Island which is also known as South Sakhalin, and that was a very demanding task because it was a very remote island, and it would have been very hard to start a temple on it. The island was then claimed by Russia about 1945, so whatever he established there was probably no longer there a few years later. In about 1938 or ’39 – I have two different accounts of that – he comes to the United States, by far the earliest Soto priest . . .”

I interrupt again to point out that Zenshu-ji in Los Angeles had been established in 1922.

“I’m making a small distinction but it’s an important one,” Tim explains. “Whilst he’s initially sent over to assist at Zenshu-ji, he very quickly then goes on to spread Zen practice to the non-Japanese Americans. Hosen Isobe, who founded Zenshu-ji, and the others with him came over to support the Japanese American population, not to spread Zen to Americans. So Matsuoka was the first to come over who was on that route. After Zenshu-ji in LA, he gets moved to Soko-ji in San Francisco to run that. And then he gets put in the internment camps for the entirety of World War II.

“After the war, instead of going back to Soko-ji, Matsuoka goes to New York to do post-graduate studies with D. T. Suzuki at Columbia. And from Columbia, he then goes to Chicago. Why he went to Chicago, I’m not sure. He happened to love Chicago, and he loved California too. So he moved to Chicago and, in 1949, establishes the Chicago Soto Buddhist Temple which later becomes the Zen Buddhist Temple of Chicago, which is still active today and is still being run by Matsuoka’s Dharma heirs. And as far as we can tell, almost from its formation, it wasn’t aimed at Japanese Americans. It was attracting, from a very early time, Americans interested in Zen. We’ve got this lack of clarity about the 1950s. We know he was based in Chicago. At the moment, I would have to guess that there was a combination of supporting Japanese Americans in Chicago and welcoming non-Japanese Americans who wanted to learn about Zen. But when we get to the early 1960s, it becomes clear that his outreach is very much to non-Japanese Americans. By the early 1960s he is very active in the Civil Rights Movement. We have a copy of a talk he gave in ’65. So during the ’60s he’s gathering a following of relatively young people. There’s a lot of hippie-like references.”

He also began meeting with other early Zen pioneers including Shunryu Suzuki and the Korean master, Seung Sahn

“And somewhere in the ’60s period, he is given the very senior title of Gondai-kyoshi, which can mean ‘highly respected authorized great teacher.’ Some translate it as Vice President of Soto-shu. Or some translate it as bishop or archbishop. And it’s the same title that Suzuki eventually gets in October of 1969. Matsuoka gets that honor substantially before Suzuki, and he’s eight years younger than Suzuki. That’s an interesting observation. Again, this is a man overlooked by history and yet he got that title.”

By the late 1960s, Matsuoka – as Tim puts it – split from Soto-shu, the formal administrative structure of the Soto school. “His very first Dharma heir was Daikaku Kongo Langlois. He’s the only person he gave transmission whose name he registered with Soto-shu. So when he made Langlois a novice priest, he did put his name down, and that would have been in ’67. Then he decides he’s breaking from Soto-shu. His Zen is going to be American Zen, not Japanese Zen, and he formally disengages from Soto-shu. I believe this is another reason he’s not mentioned, because there’s tremendous pressure from the Japanese side of things to ghost him because he left them. He stopped giving them money of course. It’s actually quite expensive to belong to Soto-shu. Thousands of dollars a year to retain title of Gondai-kyoshi, for instance. So when Langlois becomes fully transmitted in 1971, Matsuoka doesn’t report that to Soto-shu. There has also been a suggestion that Soto-shu thought they had some kind of claim over his Chicago temple because it had started as a mission to Japanese Americans, but he turned it into a mission to American-Americans.”

“And did his temple follow the same structures common elsewhere?” I ask. “Courses in zazen, extended retreats, work periods. That kind of thing?”

“Again, his approach to do Zen was not to borrow from the monastic way of doing things, and what you just described is the monastic structure. It is said that his life was one long sesshin. He led a very simple life. It was quite strict. And he retains an informal approach in each of the centers he’s involved in, because he then goes and forms a center in Long Beach, California. And Chicago and Long Beach have the same hallmarks which are that both have zazen; he has a tremendous focus on zazen; he’s very Soto from that point of view. They’re having sesshins and osesshins. They’re having talks; there are lots of talks and discussions. They had – I think they were called tea-talks – basically they were having tea and a talk. So less formal than what people were doing at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. Definitely less formal than Rinzai. And I think that’s why he attracted so many American members who were not necessarily going there to become priests. He’d make a number of priests, but that wasn’t the primary reason that people were coming. He wasn’t there to train priests in the way you do in more formal Zen centers.”

After giving Langlois full transmission, Matsuoka had him take over the Chicago center, and he moved to Long Beach.

“This is around ’71. And he forms the Long Beach Zen Temple. He becomes involved to some degree with the Long Beach Buddhist Church. I did my Soto-shu training there, and his photograph is on the altar. That’s where I first learned of him, when I asked, ‘Who’s that photograph on the altar?’ And they said, ‘Oh, that’s Matsuoka.’ I thought Matsuoka was one of the main Soto-shu people because why was he on the altar with the other Soto-shu people? So he’s the only non-Soto-shu person on the altar. And he forms this group, and it flourishes during the ’70s, and basically he stays there the rest of his life until he becomes very sick in his 90s. Then he moves back to Chicago for his remaining days. And now there is almost no sign of anything left in Long Beach.”

“What is it that you think people should know about him?” I ask. “What is his legacy?”

“Well, as I said at the beginning, the fact that he was one of the first Soto-shu priests to come to America. And he was also the first to teach Zen practice to Americans rather than to Japanese Americans. We started because you named four people as the original Japanese missionaries to America,[1] and I said, ‘Shouldn’t it really be five?’ Matsuoka should have been included in that initial list.”

“And I had not heard of him.”

“Which most people haven’t. I hadn’t heard about him until just a few years ago when I lighted upon this group, and I said, ‘Who’s Matsuoka?’ And then I dove into it. And the other thing I wanted to say is that I am still finding Matsuoka heirs. There are websites all over the world – definitely all over America – where there are Dharma heirs of Matsuoka. An Giao[2] who sadly just passed away but ran the Dessert Zen Center in Southern California is known to me as a Vietnamese monk and teacher. I didn’t know that he was also made a priest by Matsuoka. He’s all over the place. And I think his importance is that of those initial people – Maezumi, Sasaki, Suzuki, and Shimano – he’s the one who tried to come up with an American Zen rather than transplanting the Japanese Soto monastic tradition to America. So his vision, to me, was an extremely valid vision. And because he was not trying to do it monastically, it didn’t get reported on as much, it didn’t leave behind a physical temple or Zen Center that people could write about and get to know and even visit. It was more ephemeral because he tended to set up in peoples’ houses. He had a really good grasp of American culture, I think. And I think that’s another reason he should be remembered, because he’s the one who rather than say, ‘I represent Soto-shu and I’m here to convert you into American Soto-shu men,’ said, ‘I’m going to give you an American Zen that has its roots in Soto-shu, that has its roots in Dogen, in particular, but I’m trying to make it first and foremost American Zen rather than Japanese Zen.’ As one of the few remaining Matsuoka roshis, since we are the lineage bearers, it falls on my shoulders to keep Matsuoka’s memory and his teachings alive and to continue to pursue his vision of a more truly western form Zen better suited to both American and European lifestyles and culture.”

2 thoughts on “Soyu Matsuoka”