Conversations with Genjo Marinello and Kurt Spellmeyer –

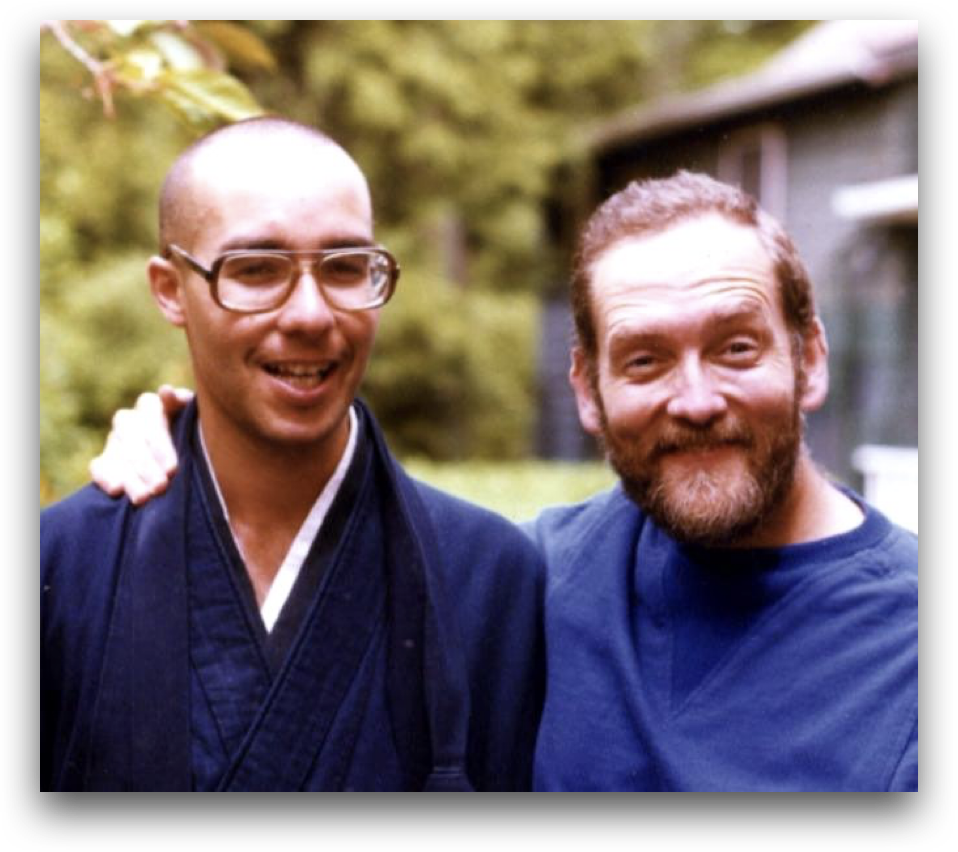

“I came to Seattle in 1976 as a VISTA volunteer,” Genjo Marinello tells me. Genjo is the abbot of Dai Bai Zan Cho Bo Zen Ji. “I had already started studying Zen in 1975 with Daizen Victoria at the College of Oriental studies and a little bit of bumping into people at Zen Center of Los Angeles, so I was already meditating daily by the time I came to Seattle. And I started looking for what was then called the Seattle Zen Center. I had heard it was on the University of Washington campus, but this was before the internet, and I couldn’t find it. I walked around campus and looked into some rooms but didn’t see anything that looked like a zendo. It wasn’t until 1977 that I met somebody who knew somebody who said, ‘This group meets at such-and-such a room on the UW campus on such-and-such a day.’ And so I showed up, and that’s when I met Dr. Glenn Webb.”

Webb was a Protestant minister’s son from Oklahoma who earned a Ph. D. in Asian Art from the University of Chicago. He had a studio in the Art History Department a UW where – Genjo explains – “there were cabinets with all the zafus and the bells and whistles, as it were, to construct a zendo by moving the tables aside and bringing out the zabutons and the zafus and setting up a zendo. And that’s what they did every week.”

Webb’s Zen practice began in 1964, when he was in Japan to study ink block prints.

“The story that I heard,” Genjo tells me, “was that he wanted to study a particular series of prints which were housed in a Zen temple – temples are treasuries of Zen art in Japan – and the roshi of the temple said, ‘Well, you won’t even see this work unless you are doing zazen. You won’t be able to appreciate it. So, why should I go to the trouble of accessing this material for you, even if you’re a scholar, if you don’t do zazen?’ So that’s how he began zazen. And then he went to a sesshin and kind of got hooked and had some experiences. He also studied the Japanese tea ceremony. And when he came back to Seattle, he taught the History of Japanese Art.”

I ask what Webb’s official teaching status had been.

“It is my understanding that he had transmission, but I never saw him dressed in the robes, and he wasn’t really playing the role of a priest or a Roshi; he was more an art history professor who had a Zen group. He was also a tea master. He had more than enough to do as a tea master and an art history professor and a part-time leader of a Zen group, but he didn’t want to be a Zen teacher. He just wanted people to have the opportunity to appreciate art and tea and felt that to do so they needed – as he had – to do Zen.”

“Do you remember your initial impression of him?” I ask.

“Affable. Sincere. Enthusiastic about everything Japanese. And I was already interested in Zen, so it was a place to come and sit. And I thought it was a great bonus, his love for everything about Japan, Japanese art, and the tea ceremony. He was fluent in Japanese, and he had spent so long there, and he had connections with temples in Japan, and I was already thinking that I might go down that path of going to Japan myself. So this was a great bonus to know an American who had done all this training.”

“You said he didn’t ‘want’ to be a Zen teacher. So he didn’t present himself as one?”

“He did present himself as a teacher of a meditation group. But he wasn’t trying to say, ‘I’m the roshi,’ or, ‘I’m the osho.’ He just said, ‘This is how to do meditation, and this is something the west could really be served by.’ So he was interested in sharing Zen, tea ceremony, and Japanese art with the world, and being an ambassador for those things. That was his way of sharing Japan with the world.”

“Did you take tea lessons from him?”

“I took a few lessons. I wouldn’t say that . . . I can whisk a good bowl of tea – yeah – and I enjoy doing that.”

“And then he recruited a teacher from Japan.”

“Yes. The group was getting pretty solid and had – even before I got there – sent somebody to Japan to train with some temple that he had been associated with. So the group was budding, and it was like, ‘I can’t do all of this. So maybe on one of my trips to Japan I’ll find someone who will be able to take over that part of leading the group.”

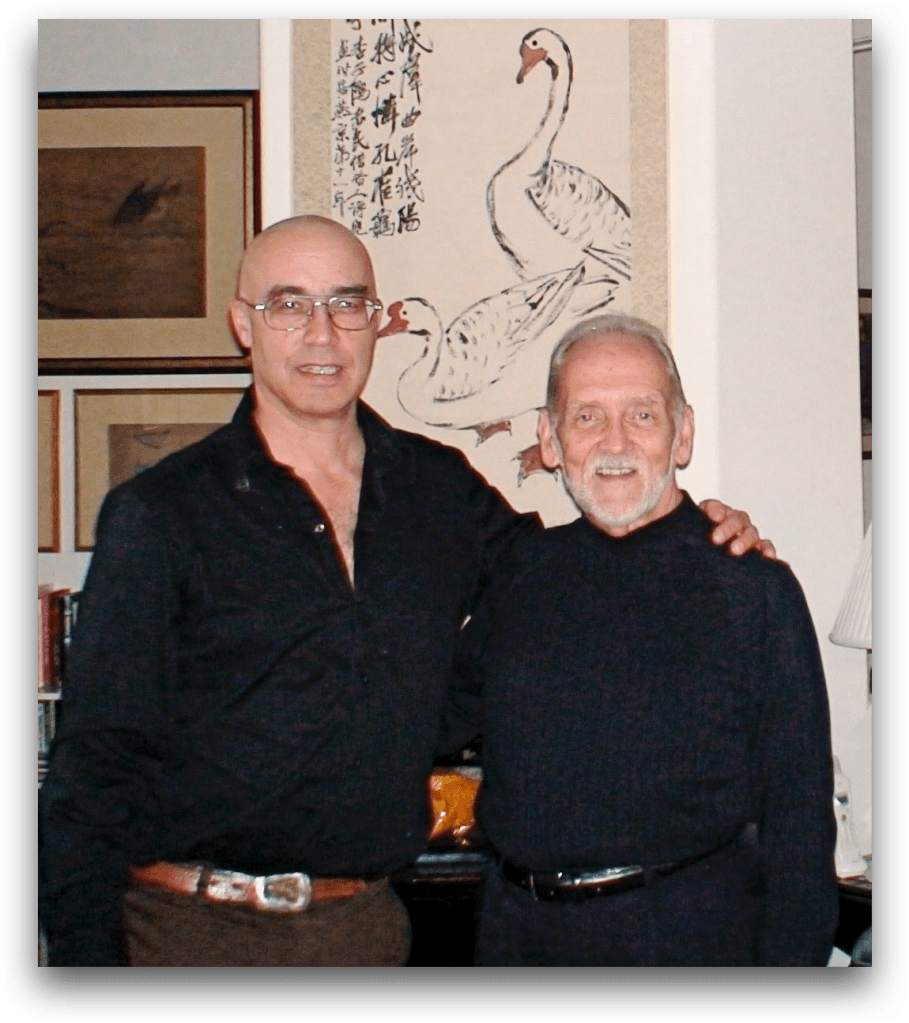

Kurt Spellmeyer is Glenn Webb’s Dharma heir. He tells me, “Originally Glenn had invited a friend, a Soto monk from Eiheiji, Hirano Katsufumi, to lead the emerging Zen Center. He had been the monk in charge of training novices there. But Hirano-san had commitments elsewhere and left. So Webb invited Genki Roshi, whom he had met through his Rinzai connections.”

“Genki Roshi” was Genki Takabayashi who had had been at Daishu-in in Kyoto at the sufferance of the abbot, Soko Morinaga, after being expelled from a previous temple for inappropriate sexual behaviour. In a letter to Kobutsu Malone, Webb explained that Morinaga had taken Genki in as a favor. “But he made Genki’s life hell: when I met him at Daishu-in he was low man on the totem pole, relegated to menial tasks and never allowed to engage in anything important. He showed no remorse for his sexual misconduct, but he seemed determined to go as far in his training as he could. He was a kind of Zen fundamentalist regarding his sitting and his adherence to the tiniest detail of Rinzai Daitoku-ji liturgy.”

Webb invited to Seattle although Morinaga disapproved of the idea. At first the situation in Seattle went well, but eventually Webb and Takabayashi had a falling out.

Genjo sighs. “Yes. It became a little like too many chief cooks in the kitchen. Something like that. Genki had such a terrible reputation in Japan and was essentially being punished. From what I understand, he was a rising star in terms of doing koan work and going up the echelons, but then disappointed and embarrassed the Japanese hierarchy by getting a woman pregnant, which was not kosher, but then not marrying her was really not kosher. And I think there were some financial dealings that he had mishandled. And so they did not think at all that he should go anywhere like the United States and represent Zen. And Genki was looking for a way out and thought, ‘I’ll just come and visit America. Maybe it will be a nice place to be.’ And he decided it was. And he was very humble to begin with. But then, as he began to pick up the adoration of Americans and the idealization of Americans, this really fed him.”

“Here, in the United States, I think at first he behaved quite well,” Kurt says. “But imagine that you’ve just come from Japan. You have all these adoring people around you, and they’re treating you like a god and that includes some very attractive women. Genki had been adopted as a child by Yamamoto Gempo Roshi; his Dharma father was a famous Zen Master who didn’t know anything about how to raise a kid. In fact, Genki was forced to attend sesshin when he was twelve years old, wishing an earthquake would pull the temple down on his head, as he once told me. So, imagine that this is your background and you’re suddenly in the United States with the Sexual Revolution underway. So he had another affair here in the US, and my understanding is this woman also had a child.”

That affair caused tension with Webb, but the community finally came apart after arrangements to buy a dedicated space for the center fell through.

“There was a house that we were trying to buy,” Genjo explains, “and Glenn was in China or out of the country, and I had put up some down payment money for this house, and even though there had been this falling out, people were still struggling to bring it all together and have our own place. And then Genki decided, ‘Well, I don’t want to live in that place.’ And, of course, it would be impossible if he didn’t live there. And Webb was pissed at him because it caused the whole deal to fall apart. And everybody was mad at everybody. And we lost – personally, my family at that time – lost the money we’d put up for the house. So everybody was mad at everybody because the house that we were trying to buy as the Seattle Zen Center fell through. Glenn was out of town. Genki was being kind of obstinate and stubborn. And that finally did it. Genki announced, ‘Well, I’m just going to start my own thing.’”

“And what did Webb do after Genki took off?”

“Glenn stayed with and remained the teacher of the Seattle Zen Center which continued to go forward independent of Genki, and the Genki faction split off. The Webb faction continued as the Seattle Zen Center until he moved onto Pepperdine in Malibu, and then the Seattle Zen Center essentially fell apart.”

“What took him to Malibu?”

“He became the head of the Art Department at Pepperdine.”

Genjo stayed with the group in Seattle and his contacts with Webb became less frequent after that.

“I would visit him in Pepperdine, probably maybe once a year or so. Then even when he retired from Pepperdine, I would go visit him in Palm Springs where he retired. And I did that a couple of times when he was retired in Palm Springs. He would come up to Seattle and visit Chobo-ji.”

Kurt chose to practice with Glenn after the break-up:

“When Genki had the affair, that crossed a red line for Glenn, and eventually our group split more or less in two. You know how divisive these events are. Whatever the initial issue might be, it becomes a focal point for other tensions and jealousies. And so it wasn’t just an argument between two people but between different groups within the community.

“When the split happened, somewhat to my own surprise, I went with Webb. I suppose I went with him because he was a deeply ethical person, thoughtful, kind and sensitive. As you know, Protestants are no more ethical than anybody else, as we can see from the endless scandals in the Protestant world, but sexual ethics are important to Protestants in a way that people from other traditions might not look at them. Webb, as a minister’s son, was deeply affronted by Genki’s behavior. For me personally, not so much. I was more troubled, even angered, by his indifference to the woman involved.

“So after we had our community Civil War, I was ready to quit Zen. It was so discouraging. People had to choose sides and were attacking one another, impugning each other’s motives. It was ugly and sad. People who had sat through sesshins side by side were suddenly yelling at each other. It was like a nightmare, and I’d just had it. I decided that I would quietly bow out, as many other members of our group did at the time. But all the same, Webb was organizing a sesshin. We had built a temple up in the mountains, which we were now about to lose because financial support had dried up, but Webb was going there one last time before we put the place up for sale. One evening after meditation, Glenn approached me and asked if I planned to attend. And I very much wanted to say no, but when I looked at his face, I thought, ‘I can’t do this to him. He’s organized this last sesshin; I can’t say, “No.”’ And when I arrived at the temple, instead of our usual eighteen or twenty people, I think we had five – Webb and four others including me. Arriving at the empty, half-finished temple, I felt quite sad and lonely, but that was where I had my dai-kensho, my great awakening experience. It was like nothing else ever. I think I cried for seven days, and at first I wasn’t even aware that I was crying.”

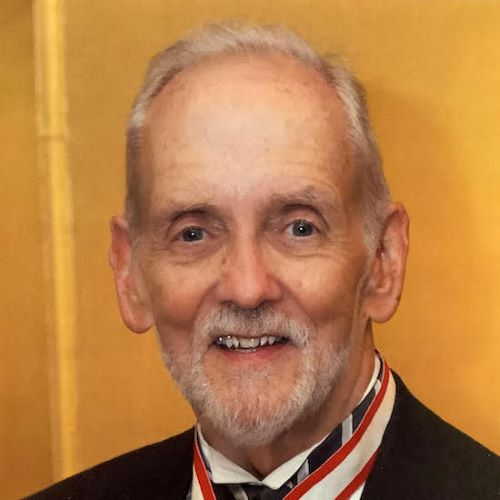

Glenn Webb died on January 6, 2024. I ask Genjo about his legacy.

“He was a key transmitter of the love and art of Japan. From Japan to the West. A little bit like D. T. Suzuki, on a smaller scale of course, but bringing the love of Japanese art and culture from Japan to the United States and having it appreciated on a much wider scale. Whether it was the art of flower arranging or the tea ceremony or sitting zazen or appreciating any of the other Japanese arts, he was just this wonderful ambassador of Japanese culture to the West.”

🤩

LikeLiked by 1 person