The Diamond Sangha –

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese warships encircled the island of Guam. American military personnel posted there were outnumbered and surrendered without a fight. Robert Aitken, who had been working construction on the island, was among the civilians detained and transported to Japan as non-combatant internees.

He was first incarcerated in the old British Seaman’s Mission in Kobe which had a library to which the detainees were allowed access. Aitken decided to make the best use he could of his imprisonment by improving his general literacy. The book that redirected his life, however, did not come from the library but was loaned to him by one of the guards. It was Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics by Reginald Horace Blyth, who had taught English at the high school the guard had attended before the war.

Blyth’s Zen was literary. He didn’t practice zazen but valued Zen insight, which he believed was universal. In his book, he sought to demonstrate that Zen themes—such as the quest for enlightenment—were common throughout world literature. Zen, as he understood it, was found not only in China and Japan but as well “in Christ; in Eckehart [sic], and in the music of Bach; in Shakespeare and Wordsworth.”

It was an unorthodox approach to the subject but an ideal introduction for Aitken, who already admired Japanese haiku poetry. He reread the book so often that the guard, fearing the binding would break, took it back.

Coincidentally, Blyth was not far away in another camp for civilian prisoners where, in spite of his Japanese wife, he was detained as an “enemy alien.” In 1944, the prison camps in the area were combined, and Blyth and Aitken were housed together in the same complex. They met, and Blyth introduced Aitken to D. T. Suzuki’s Essays in Zen Buddhism.

Nelson Foster is one of Aitken’s Dharma heirs and was his immediate successor as teacher at the Honolulu Diamond Sangha and its sister group on Maui. He tells me that, in a peculiar way, Aitken’s time as a prisoner of war was a period of personal growth. “He was fascinated by Blyth. Bob was a guy who’d flunked out of college. This exposure to literature through the super well-read and linguistically talented Mr. Blyth lit him up intellectually, and when he got back to the United States, he finished his bachelor’s degree, then went on to a master’s degree in Japanese literature. So in many ways, that time in Japan ignited Bob Aitken, turning him from a college drop-out to a fellow who found his feet in the world and really got started.”

After the war, Aitken earned an English degree from the University of Honolulu in 1947, following which he and his first wife, Mary, left for California where he planned to do graduate studies at UC-Berkeley. He remained interested in Zen, and when he heard about Nyogen Senzaki in Los Angeles, he and Mary relocated there, transferring his graduate study to UCLA.

His first meetings with Senzaki were discussions about philosophy and literature. Eventually, drawn by Senzaki’s personal manner, Aitken realized that what he wanted was not information about Zen but a way to develop the insight which animated Senzaki. The Aitkens joined Senzaki’s meditation group, and Senzaki assigned him, as a koan, Meister Eckhart’s statement that “the eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me.”

In 1950, the Aitkens returned to Honolulu, where he completed his master’s degree at the University of Hawaii. When Aitken expressed an interest in returning to Japan in order to pursue further Zen training, D. T. Suzuki helped help him obtain a fellowship to do so. Mary had recently given birth to their son, Thomas, and remained in Hawaii.

Aitken took part in a week-long sesshin at Engakuji under the direction of Asahina Sogen. This was Aitken’s first experience of extended zazen. Although he was thirty-three years old and not very flexible, he was expected to sit in the traditional cross-legged posture for ten to twelve hours a day. There was no formal instruction given to the participants, although the monk seated beside Aitken in the zendo had responsibility for showing him zendo protocols. When they were introduced, the monk said, “How do you do? The world is very broad, don’t you think?” Aitken admitted later that he had no idea what the monk meant but was, nevertheless, charmed.

As the sesshin began, Aitken enthusiastically took his place on the tan (platform) where the monks were seated. The atmosphere in the zendo was all he had imagined it would be – incense burning, black-robed monks steeling themselves for the ordeal ahead, the sounds of the various clackers, drums, and bells, even the staccato chanting of the opening ceremonies – then the teacher got down from the tan and prostrated himself before the altar and the image of Manjusri, the Bodhisattva who oversees sesshin. Nine times, Asahina Roshi lowered himself to his knees and bent forward until his forehead touched the floor. Aitken was appalled to realize that he, too, was expected to prostrate himself before the statue. His western sense of dignity and a cultural aversion to idol worship rose up in protest. He had not fully comprehended until that moment that Zen was more than a psychological practice; it was a religion.

In the private interview called dokusan, he informed Asahina that Senzaki had assigned him the Eckhart statement as a koan, and Asahina told him, instead, to meditate on Huineng’s “Original Face” which, he explained, had the same intent. The koan demands that the student “show his face before his parents’ birth.” It was difficult to remain focused on it, however, because Aitken struggled both with the pain in his legs and rising doubts about the ritual elements of the sesshin.

He persisted, however, and, in December, returned to Engakuji to take part in the Rohatsu sesshin. Still unused to cross-legged sitting postures, Aitken found the ordeal even more excruciating than the November sesshin had been and, in desperation, thought to search elsewhere.

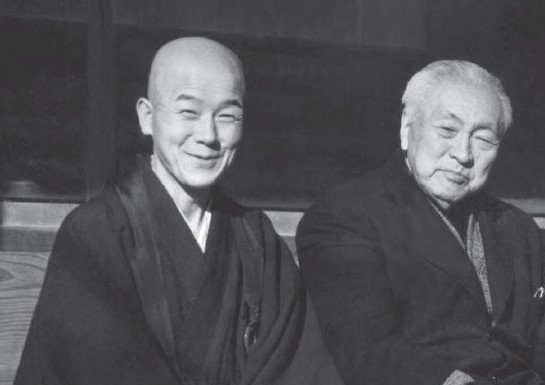

Nyogen Senzaki had spoken of his friendship with the Zen monk and poet Soen Nakagawa. Aitken wrote to Nakagawa and received an invitation to visit Ryutakuji. The men shared an interest in haiku among other things and got along well. Nakagawa explained that it was not unusual for Zen students to attend sesshin at a number of temples and with different teachers until they found the one best suited to them. He suggested Aitken take part in the January sesshin at Ryutakuji.

The teacher at Ryutakuji, Gempo Yamamoto, felt that Aitken’s approach to “Original Face” was too intellectual, so he assigned the American Joshu’s Mu, which allows no room for rational analysis.

Aitken later wrote: “I felt a little resistance to this change, but on returning to my cushions, I discovered what zazen really is. No longer was I aware that the cracks in the tile floor formed a weird pattern. I could sink at last beneath the surface of my mind.”

Once back in Hawaii, he needed to focus on earning a living and supporting a family; however, things did not work out well. His marriage unravelled and, after his divorce, he returned to Los Angeles in order to continue study with Nyogen Senzaki.

In 1956, another of Senzaki’s students told Aitken that the Krishnamurti School in Ojai was in need of an English teacher. Aitken applied for the position and was interviewed by and hired by the school’s assistant director, Anne Hopkins. Within a year the two married. It proved to be an auspicious union.

Their wedding trip to Japan was not, however, what most newlyweds would have considered a honeymoon. The day after their arrival, Aitken went to attend sesshin at Ryutakuji, where Nakagawa had been installed as abbot. Anne supported her new husband’s desire to take part in the sesshin but had no intention herself of spending seven days sitting immobile with aching knees. Nakagawa made one of the monastery’s guest rooms available to her.

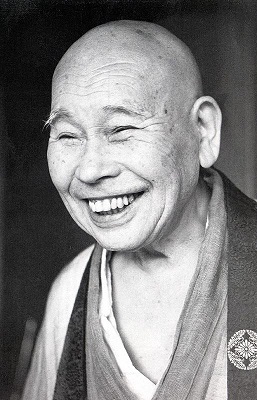

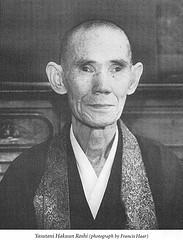

Later, in August, they went with Nakagawa to a small temple outside Tokyo where Nakagawa—although a Rinzai Zen Master in own right—was attending a sesshin and serving as assistant to a teacher from the Soto tradition, Hakuun Yasutani.

Again Anne had not intended to take part in the sesshin but was inspired to do so by the example of an elderly woman in the house where she was staying. Yasutani provided her a western-style straight-back chair and invited her to attend dokusan if she wished. It was those private meetings with Yasutani that washed away her resistance to zazen, and by the end of the sesshin she was making a serious effort.

Two of the participants in the sesshin attained kensho, and, while Aitken had not done so himself, he was convinced, in a way he had not been before, that awakening was achievable.

That May, Nyogen Senzaki died, and Soen Nakagawa went to Los Angeles to perform the funeral rites and hold a memorial sesshin in Senzaki’s honor. It was the first full seven-day sesshin to be conducted on the US mainland. Both the Aitkens participated.

They then moved to Honolulu so Aitken could be nearer his son. “They opened a bookstore in the Chinatown area,” Don Stoddard tells me. Don began studying with Aitken in 1968, four years earlier than Nelson had. “And they had a section in the bookstore labeled ‘occult’ that would contain the theosophical titles and also Buddhist and Indian philosophy. They kept track of people who bought books out of the occult section to create a mailing list. So, when they were going to have their first sitting at their house, they invited people on the list to come and do zazen. And one couple came,” he adds, laughing. “So that’s how it began. Didn’t have a name yet. Then Soen Roshi came for the first sesshin that was held there. It is a very nice location, kind of an upper-class area still in Honolulu. It’s on the ocean, looks south-southwest, and it’s near a prominent feature that’s called Koko Head. When Soen asked what the name of that was, they told him, ‘It’s called Koko Head.’ So, he decided that the place should be called Koko An, which in Japanese means, ‘The little temple right here.’ When the Aitkens later moved to another house in Manoa Valley, close to the university, that also became Koko An.”

In 1961, Nakagawa led a sesshin at Koko An which Aitken approached with determination. He put as much vigor into his sitting as he was able to muster and continued late into the night after the formal meditation periods had ended. Then, on the fifth day of the sesshin, Aitken writes, “—Nakagawa Roshi gave a great [shout] in the zendo,and I found my voice uniting with his, ‘Aaaah!’ In the next dokusan, he asked me . . . a checking question. I could not answer, and he simply terminated the interview. In a later dokusan, he said that I had experienced a little bit of light and that I should be very careful.”

Between 1962 and 1969, Yasutani made a series of regular visits to the United States and conducted sesshin in Hawaii, Los Angeles, and on the East Coast. Aitken took part in as many of these as he could and was now considered a senior student.

In 1967, Aitken turned 50. Anne was 56, and they began to think about their eventual retirement. They fully intended to continue their Zen activities, however, and to that end purchased an old farmhouse at 220 Kaupakalua Road on Maui. In 1969, the Maui Zendo was formally established there. It had a quasi-monastic program with daily zazen, gardening and other manual labor, frequent day-long sits – zazenkai – and sesshin.

With the Aitkens in residence, Don tells me that “a fairly stable group of residents and community members were practicing together.” It ranged from young social “dropouts” to retired couples. After one sesshin, seven attendees were confirmed to have achieved kensho.

Don had been stationed in Hawaii while in the Navy, and he remained there after his tour of duty ended. When he was younger, he had read a few books on Zen which he enjoyed, and, in 1966, he came upon a copy of Philip Kapleau’s newly published The Three Pillars of Zen. “I’d been sitting by myself, and at that point I thought, ‘You know, there must be groups around.’ I tried in Honolulu. I’d gone to the Soto temple, I’d gone to other places, but there was no active sitting going on in those local Buddhist organizations. So, I wrote to Kapleau in care of his publisher, got back a postcard, and it said, ‘Contact Robert and Anne Aitken. They’re in Honolulu.’ With a phone number. I called up. Anne answered. I told her I had been sitting and was looking for a group to practice with. She said, ‘Well, we’re sitting tonight. Why don’t you come up early and speak to Bob, my husband, and he’ll talk to you and show you what the forms and procedures are.’”

“I met Robert Aitken first as a disembodied voice,” Nelson Foster tells me. “It was 1972, the summer between my junior and senior years of college. I stumbled suddenly into Zen practice at Koko An Zendo, in Honolulu, where my family lived. And on Wednesday or Sunday night after zazen we would have tea and listen to a tape made by Bob Aitken. He was not Aitken Roshi at that time; he was Bob. He and Anne were spending an extended period – two or three months – in Kamakura in order to do intensive study with Yamada Roshi, and every week or so he’d send us a cassette tape recording in which he recounted interesting events and observations.”

Nelson met him in person at the end of the summer. “We were told to think of him as our elder brother in the Dharma. He hadn’t yet received a formal appointment to teach but was in a sort of apprentice capacity to Yamada Roshi. He had a little bit of an austere aspect. A tall, thin man, rather reserved in his manner. Friendly but reserved.

“Koko An was never large,” Nelson says. “It was a nice old home in a pleasant urban district of Honolulu; the living and dining rooms had been converted into the zendo. It probably seated twenty-two or so, something like that. On a Wednesday night, as I recall, we’d usually occupy just the living room, so a dozen people or thereabouts. There were a few old-timers both in age and in terms of their tenure as members of the sangha.”

The following year, Nelson joined the community on Maui and discovered there was a difference in character between the two communities.

“Maui was mostly a gathering of the younger slice of the sangha. There were a couple of seniors who had retired to Maui, but almost all of us were young, in our twenties. Some younger but very few older. There was much more of a back-to-the-land, hippie – if you will – and questioning spirit to the group on Maui. They were members of the generation that was rejecting the war in Indochina, questioning existing authority, trying marijuana and other substances, and looking for a new way to be in the world. Koko An had started earlier and had a base of practitioners with more years of practice. And it was more mature in the age spectrum as well. A couple of years before, when the Aitkens moved over to Maui to start the Maui Zendo, they rented out Koko An, and by 1972, the people who lived there, mostly in their twenties, were required to participate in zazen five days a week, but the scene was pretty loose by Zen standards. The senior occupant was a practitioner of biofeedback who’d actually sit there during zazen plugged into his biofeedback device. It was a group finding its way, by no means homogenous. Actually the president of the sangha at that time was a Korean doctor, a man with grown children, whose wife also was a member. It’s hard to make any tidy generalizations about the group. The atmosphere was welcoming, though.”

After Yasutani retired, his successor, Yamada Koun Roshi, came in his stead to Hawaii to lead sesshin, and it was Yamada Roshi who authorized Aitken to teach in 1974, making him the first North American to receive transmission in the Sanbo Kyodan tradition.

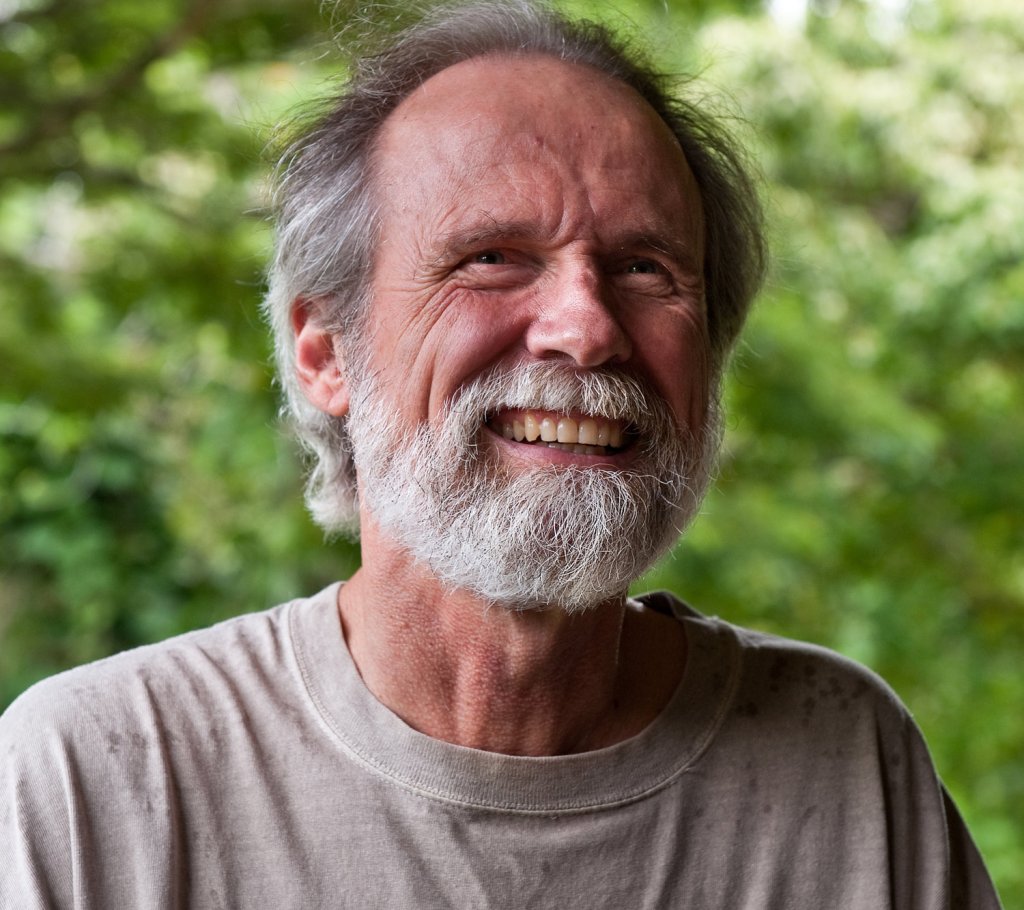

Don tells me, “Yasutani Roshi came in 1969, led sesshin in Honolulu and Maui. That was the last time he came. And then the transition was made to Yamada Roshi, who was his successor. A couple of years later, we started to call Bob ‘Aitken Roshi,’ although he later expressed regrets about that because when he was still ‘Bob,’ if the gang was going to get together and get into somebody’s VW bus and go down to the beach and have a good time, well, Bob would go along. But when he became Roshi, the invitations didn’t come. He had liked the intimacy of just being ‘Bob’ with the other folks.”

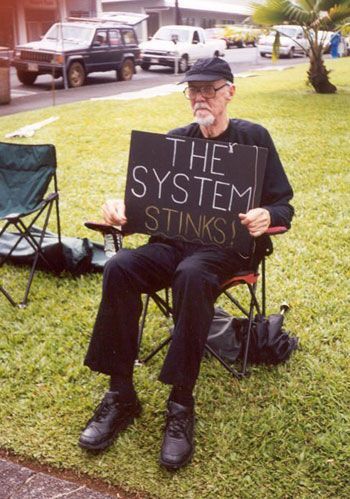

In addition to his work as a pioneer Zen teacher in the West, Aitken was actively involved in a number of social justice issues including opposition to the US military intervention in Vietnam.

Nelson continued, “I would say that, when I got to know him, it was a pacifist orientation that was first and foremost for him, but his politics were progressive across the board.” Aitken’s internment increased rather than diminished his anti-war sentiments. “His direct experience of seeing Japanese families with their belongs on their backs escaping from the [U.S.] bombing and the destruction of all of their life left a lasting impact,” Don explains. “His pacifism was very deep, very serious.”

I ask Nelson if the sangha members in general were equally concerned about these matters.

“Some members were, and some members weren’t. That was important to him too, that he didn’t insist on anybody sharing his politics. While I was living on Maui, the Aitkens and I and others founded the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. He and I became members of its initial board of directors, but others in the Maui sangha never joined it.”

“At his retirement gathering,” Don tells me, “I gave a welcoming speech, and I said I’m sure that he was disappointed over the years that many of the people that he was practicing with for long periods of time didn’t join him in these activities. But then I made the point that, in the dokusan room, it never made any difference. He did not favor or disfavor people along this particular dimension.”

I ask Nelson, “How would you like him to be remembered?”

“I’d hope people would remember Aitken Roshi as a man who loved the Dharma, who loved the tradition and did his utmost to convey it in a vigorous and true way that was thoroughly consistent with ethical living. He was an upright guy. He felt it was extremely important to live rightly in one’s economic relations, political relations, social relations, in all aspects of one’s life. That was deeply stitched into his character. When the painful, painful news came out not just about [the sexually inappropriate behavior of] Eido Shimano but the scandals surrounding Richard Baker Roshi and Taizan Maezumi Roshi, he felt confirmed in his concerns about such things, and he ratcheted up his own emphasis on what he considered the implicit ethics of practice and realization. There’s no question that the collapse of dichotomous thinking implies, for example, right relationships with non-human beings of all kinds. So the environmental movement was a natural for him. The women’s movement was a natural for him. Those concerns all came in addition to his longstanding concern about war and peace, honesty, fairness.”

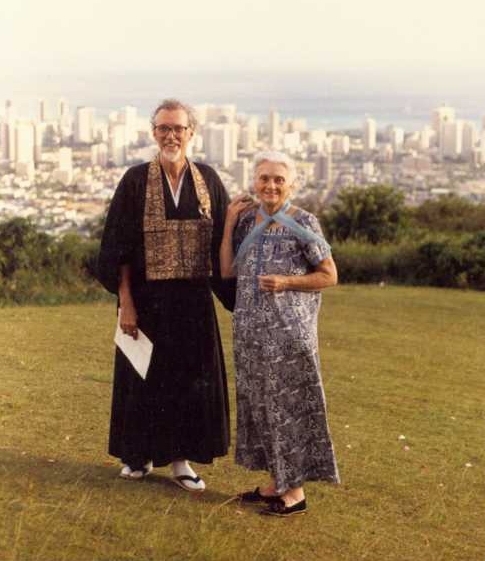

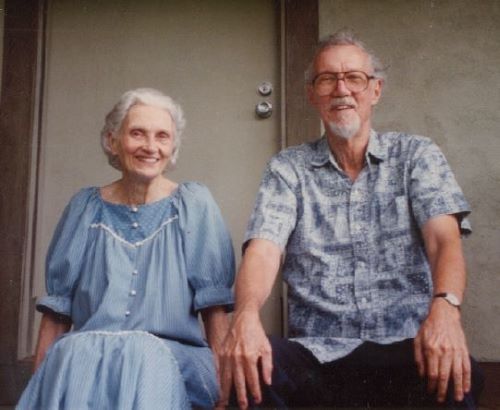

Throughout the conversations, both Nelson and Don emphasized that Anne’s role in the development of the Diamond Sangha was nearly as important as her husband’s.

“She was a generous donor,” Nelson says. “A gracious and motherly presence. A very dedicated practitioner herself. A sweet, lovely person dedicated to Aitken Roshi and a source of tremendous support, in ways ranging from domestic to financial to in-house critic of his work, first reader of things that he was going to publish eventually.”

“I’ve heard from others that she may also have shared some of Aitken Roshi’s anti-establishment views,” I mention.

“Well, he was sort of a black sheep of his family, and, in many respects, she was a black sheep of hers. She came from a wealthy San Francisco family but was artistically inclined and married a fellow who was never going to make it big in business, who eventually became a Zen teacher, of all things!”

“Anne was a wonderful person,” Don says. “Warm, welcoming, supportive in all respects.” He describes her looking after the younger members of the Maui community. “A lot of the young people that came to Maui were the so-called hippies of the time. And so, when Anne got up each morning, when it was residential, she had to make sure that the people who needed to take pills had taken their pills so that they didn’t spiral down. She was foundational to the success of the community. If you contact any of the female members of the sangha from the early days, you will find out just how important she was. She would find ways – if they didn’t have much money or any at all – she would create jobs, whether it was sewing or mending clothing, or she used to sometimes bring out broken crockery on a tray and they could spend time putting it back together Japanese-style.”

Anne died in 1994 at the age of 83. Robert retired a year later. He lived another fifteen years, and by the time of his death in 2010, he was recognized – as Helen Tworkov put it – as the “unofficial American dean of Zen.” It can be argued that Zen as a discipline that would come to draw hundreds of practitioners, rather than a largely literary phenomenon, started in 1959 with the arrival of Shunryu Suzuki in San Francisco and the establishment of the Diamond Sangha in Hawaii.

6 thoughts on “Robert and Anne Aitken”