Salt Spring Zen Circle, British Columbia

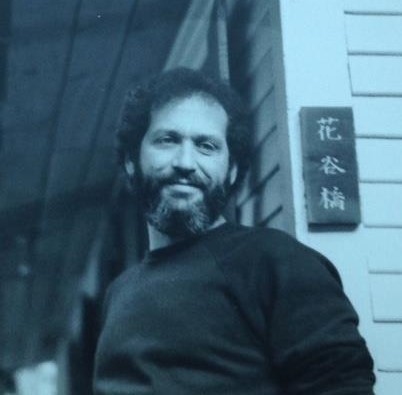

In early 1967, at the age of 21, New York-born Peter Levitt and his wife heard something was happening in San Francisco, so they headed west.

“We rented a place in the Mission District that had four apartments, which was a great find,” he tells me. “Rent was $80 a month and right after we moved in with furniture from the Salvation Army down the block, we headed to Golden Gate Park where we had heard lots of good things were happening, and especially free live music. And, just coincidentally, upstairs from our apartment there was a very lovely woman named Hazel, who a few months later started seeing a young guy who was deeply interested in Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan practice wasn’t a particular interest of mine at the time, but I had already been taught to meditate, so there is a way in which this young man did have my ear. After all, San Francisco in the Sixites was exploding with what, for me, were new ideas, and I was an open shop.”

In New York, one of Peter’s friends showed him how to meditate in Zen style. “It was in the air,” he laughed, “along with Eastern spirituality and philosophy, which interested me from the start.” Also, when he was briefly a third-year music major at NYU, he learned to chant by going to a “storefront temple” run by the Hare Krishna people where there was a lot of delicious, unusual, free food, and other young people having what seemed to be a good time.

“When I got to San Francisco, the rose of eastern spirituality was starting to open out for me because I already liked sitting quietly in meditation and chanting, and I enjoyed talking with the young man from upstairs about Tibetan Buddhism. He also brought to my attention the novel Mount Analogue by Rene Daumal, and Lama Govinda’s The Way of the White Cloud. I thought, ‘This young guy is really well read!’ And there were a few books I’d picked up on my own, plus the nonstop conversations with like-minded friends and people I’d meet in the park.

“Then one day I went to the Salvation Army store just down the block from our apartment, and I saw a book on the used bookshelf called Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, which cost all of ten cents. And as I walked back to our place, I opened it, read a little, and I just started to laugh. ‘This is crazy shit,’ I thought. But it excited me, so I read another page, and thought, ‘I have no idea what’s going on here, but whatever it is, it’s really good.’

“But when I came to a page and read, ‘We know the sound of two hands clapping, but what is the sound of one hand clapping?’ it stopped me cold. Now there’s background to that. When I was 13, I used to save up and buy classical music and comedy records, and one of the records I bought was by Shelley Berman, who recorded comedy routines he did in front of a live audience. In one of his routines he said, ‘We know the sound of two hands clapping, but what is the sound of one hand clapping?’ And the audience burst into laughter, and I did too. But, of course, I didn’t know why we all were laughing, or what he was talking about. It just seemed so absurd. So when I was 21 with my new book in hand I came upon those words again, which of course is the famous koan by Master Hakuin, and it reminded me of the comedian. And all of a sudden I was laughing again, even more than I did as a kid, though I still didn’t know why. But now it was in the context of Zen, which was part of the larger context of all these other new things in my life, things I also didn’t quite understand, but that thrilled me and made me curious to know more.”

“And so once when this young man dating Hazel came downstairs and gave me these Tibetan books to read, I found myself saying, ‘That’s a bit too complicated for me. I like this Zen stuff.’ And he said, ‘Well, what do you like about Zen?’ And I told him, ‘I don’t know, but I like that I don’t know why I like it, and, besides, it seems pretty simple, which appeals to me and adds to the mystery. And call it irony or call it karma – which I’m not sure anyone really understands – but the young man was Sam Bercholz who would go on to found Shambhala Publications, and in later years become one of my publishers.”

Peter heard from friends about an “incredible Zen master from Japan” teaching in San Francisco – Shunryu Suzuki – but Peter tells me he had no interest in going to see him. “There’s a certain irony in that, given that I’ve ended up a teacher in his lineage, but at the time, 21 years old in hippie heaven, I didn’t want any institutional anything. I just wanted to stay with myself and this burgeoning awareness/suspicion that maybe there was a home for me in some way, a spiritual home, without any interruption of that personal investigation from any source at all, even a reputedly great Zen master. Maybe it was my age, or the times, and maybe it was just me nursing this sense of something new that I wanted to explore on my own.

“I have a certain shyness that connects somehow with a love of that internal study and process. It’s like a room inside myself that’s very quiet where I can hear myself. It was the same with poetry as it emerged in my life. And so I stayed away, though increasingly I meditated more, read more books, and let my imagination touch the world at the same time that I was developing a sitting practice and working hard on my writing to figure out, as I thought of it at the time, ‘how to get said what must be said’, which is another way to articulate a major question I had as a young man, namely, in a world that makes little sense to me, how should I live?

“I was writing constantly, and sitting zazen on my own, and in 1969 my wife and I went back east to the university in Buffalo where she wanted to complete her BA. My poetry life really began to flourish there because Buffalo was a poetry hub with many good and even great mid-century poets and writers either visiting for a week at a time or teaching year-round on the faculty. And to my amazement, thanks to the New York poet Ted Berrigan who was there, my poems were starting to be published.

“Then, in ’71, we had a baby, but because she wasn’t able to adjust to the harsh winters, her doctor suggested we head back west to a drier climate. So, in 1973 we packed up ourselves, our baby, our dog, our cats, and drove back to the West Coast. This time landing in LA.

“By then I had become friends with other poets and writers, mostly those I’d met and studied with at Buffalo, including Robert Creeley, Ginsberg, John Logan, and another poet who had become very important to me, Diane di Prima, who became something like an older sister; very present, protective, and supportive of both my life as a young poet and as a Zen practitioner. It was a fortuitous time for me, and in 1979 Creeley graciously wrote the Foreword to Running Grass, my first full poetry collection, which Diane published through Eidolon Editions. And, as for Zen, I continued practicing on a daily basis, full-on, though still in my own reclusive way.

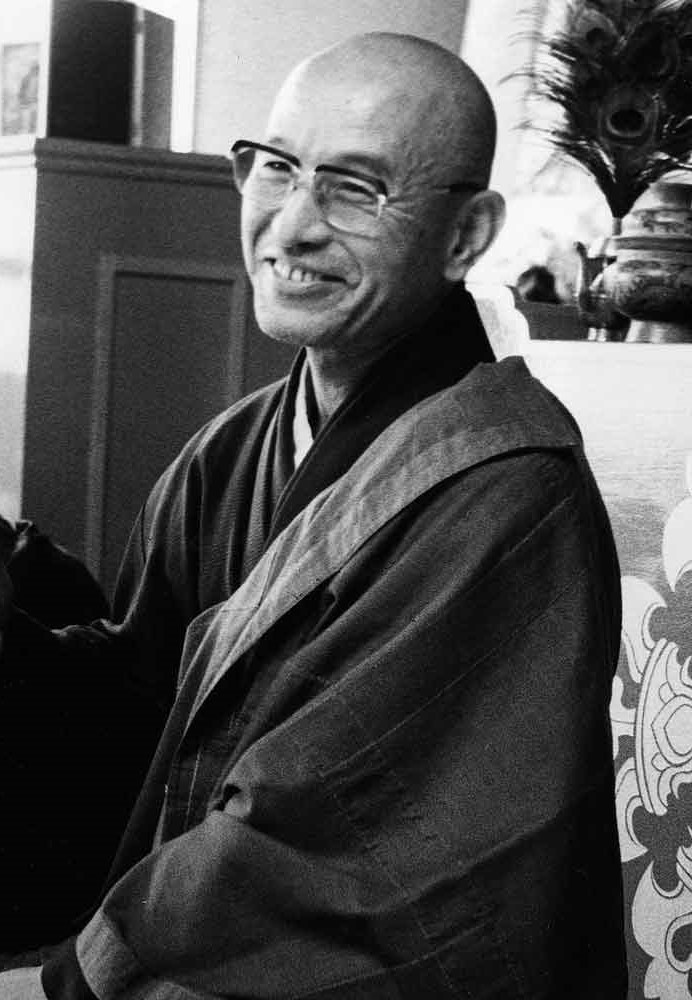

“Years later, after being settled in LA, I went to Zen Center of Los Angeles and did a sesshin with the Zen master there, Taizan Maezumi Roshi. I have to say, my first dokusan with him was really wonderful. And it was funny, too. The priest there told me that when my turn came and I hear the bell, I have to get up quickly, leave the zendo, run down the hallway despite these long robes I’d never worn before, stop at the door where someone’s going to come out, and then I go into the room, bow at the altar just inside the door, and go in to see the master. I have to laugh because all I could think of was how I was going to run and not trip on my robes and end up falling on my face. When you get inside, they told me, after you bow at the altar, step over and bow to Roshi. And then you’ll have dokusan.

“So, since this was my first meeting with a Zen master I thought, ‘What the hell? If this is Zen, I’ll do it.’ So I did just as they told me, and all of a sudden, I found myself sitting up on my knees in front of Maezumi Roshi with our faces this close.” He holds his hands about a foot apart. “We were so close I could hardly see the outline of his face. But in that quiet little room, with my heart pounding from all the rushing about, suddenly I could hear a kind of soft whisper and noticed his robes begin to move. I was afraid to look down, but I saw some movement and thought, ‘Uh-oh. I read about this. This is where they hit you!’” We both laugh. “And then I saw his hand come up between our two faces, and he went like this.” Peter crooks his finger. “Come closer. But we were knee to knee so there was no way for me to come closer to him. And what I understood was, ‘Just come closer. Not to me. Come closer to everything; to yourself.’ That’s how I understood that crooking finger.

“Then I looked up and saw this big smile on his face. That’s when he said the first words that any Zen Master ever said to me, ‘You’re Jewish!’ And I said, ‘Yes. I am.’ And I knew he was just saying, ‘I recognize that you have a Jewish face.’ Nothing other than that. And then he told me, ‘That’s wonderful. Wonderful. Everybody wants enlightenment.’ And I thought, ‘This guy is great.’

“After that, we had a wonderful conversation. It turned out we both loved the same Japanese poet, Miyazawa Kenji. So I felt very welcomed, and after he asked if I had any questions about practice, I went back out to the zendo feeling, ‘Okay. I can do this.’

“Later, Maezumi came into the zendo and gave his daily Dharma talk and said, ‘We’re fortunate at this sesshin; we have a real poet with us.’ He didn’t mention me, which would have been embarrassing, but he talked about poetry in a beautiful, erudite manner, and its place in Zen. I was enthralled.

“I was sitting very deeply during that sesshin, and the next day I was invited for dokusan again. This time Maezumi Roshi asked, ‘Do you have any questions about your practice?’ I said, ‘Yes. I don’t know how to say this, really, but while I was sitting this morning, I saw all these golden Buddhas in my mind or imagination, and they were bowing. I’m not saying that they were bowing to me, that would be ridiculous, but this is what I saw.’ And showing no expression on his face, which I was scouring for a clue, he just cleared his throat and said, ‘Um.Things are not so good.’ I was surprised. ‘Really? What was that, then? What was going on?’ ‘It’s just makyo,’ he said. ‘Just delusion; treat it like any other delusion. Ignore these Buddhas and go back and do your practice.’

“Then he rang the bell and sent me back to the zendo. It happened in a flash, and I was thrilled, really, because I had practiced so long by myself, and here this Zen master was teaching me, showing me that Zen is not about Buddhas bowing, or any special-seeming experience; it’s just about, ‘Forget that stuff! Go back and do your practice.’”

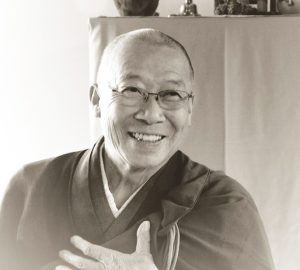

As it happens, as close as he felt to Maezumi, Peter continued to practice mostly on his own, though he made visits to ZCLA where, he said, Maezumi Roshi always treated him with great generosity, making time to talk with him whenever Peter asked. Over the succeeding years, Peter became an established and respected poet and translator. One marriage ended, another began, and during the early years of that new relationship Peter heard Jakusho Kwong, dharma heir in the Shunryu Suzuki lineage, speak at an event at the Naropa Institute, which Peter attended with Diane Di Prima.

“As Diane and I found our place to sit, I saw a Chinese man dressed as a priest walk along the side of the crowded hall in what I thought was a fairly modest, almost shy way. Then he stepped up onto the stage and sat down. Diane said, ‘That’s my friend, Bill.’ She knew him from her days practicing with Suzuki Roshi. Bill, as she called him, was Bill Kwong, known at the time as Kwong Sensei, and a few years later, after I became his student, as Kwong Roshi.”

“He bowed with the audience and then gave his talk. I have to say that both his shyness and the talk he gave really appealed to me. It was apparent that he didn’t have lots of fancy words or concepts to convey, but rather he talked about what it was like to wake up early in the morning before zazen and have to find his socks beside his bed in the dark room, and then put them on without knowing where the heel was. That was it, and he acted this out in a way that had all of us laughing with recognition. He didn’t want to wake his wife on the days she wasn’t joining him for zazen – since she had their four kids to care for – and he was careful not to make any noise or turn on a light. So he’d just search in the dark, then make his way from the bed to find the door, where he’d run his hands down the door frame to find the doorknob, all of which he acted out. And then, with a slight pause, he gave what I considered the full dharma talk in one sentence, ‘If you want to go through a door, it’s good to know where the doorknob is,’ which I heard in a completely symbolic way.

“About five years later, around 1983, everything was going well in my life. I was married again. It wasn’t an easy marriage, even in its early years, but there were many elements we shared from the beginning, including a love of poetry, the act of translating poetry from Chinese, and Zen practice. Also my daughter from my first marriage, who lived with me most days of the week, was doing well. So, on the surface, everything seemed pretty good. But despite this, I felt this huge hole right in the center of me. ‘Something’s wrong,’ I said to myself. ‘Something’s just not right.’ But I couldn’t figure out what it might be. As you know, life gives us these quasi-koans from time to time.

“So, I called Diane, and told her, ‘Everything’s great here, but there’s this huge hole in the center of me.’ And she said, in her usual quick and knowing way, ‘Oh, honey, it’s time for you to come in out of the cold. You’ve practiced alone long enough. It’s time for you to take Precepts.’ And as soon as she said it, I just wept because I knew that she was right. ‘It’s time for you to take jukai.’ And as soon as she said that an image flashed in my mind and I asked, ‘Do you remember that Chinese Zen priest friend of yours that we saw at Naropa?’ Now, this is interesting because for some reason – maybe because I was talking with Diane – I didn’t think of Maezumi Roshi who I liked so much and had practiced with. I thought of this man that I knew nothing about. But intuitively I felt there was something there, so I went on, ‘I want to take Precepts with him.’”

Peter became Kwong’s student, took jukai, and studied with him for twenty years, during which time Kwong authorized him to establish a Zen sitting group, the Topanga Zen Group, which practiced in a small zendo he built at his home. Kwong later invited him to give “senior student talks” at the Sonoma Mountain Zen Center, and Peter served as shuso leading the summer practice period two years running. However after Peter edited Kwong’s first dharma book, No Beginning, No End, Peter decided to conclude their dharma relationship.

“During these years I was ‘supporting my poetry habit,’ as I called it, and paying the bills by teaching two poetry writing workshops a week. The poets I worked with were a joy and many of them stayed in this little community of poets for about twenty years, with publication increasing as the years passed. And, of course, because we talked in those workshops about every aspect of life, Zen practice was part of the conversation. Students knew I meditated every day, of course, and gradually some of them wanted to learn about meditation, so they came to sit with me at our little zendo. Kwong Roshi came down to initiate it as a place of practice, which I appreciated. Coincidentally, Robert Creeley was staying with me when Roshi came down so here it was; two major aspects of my life meeting in the outer world. My second marriage ended during that time, just as the zendo was being completed, so I had the property to live in with my daughter.”

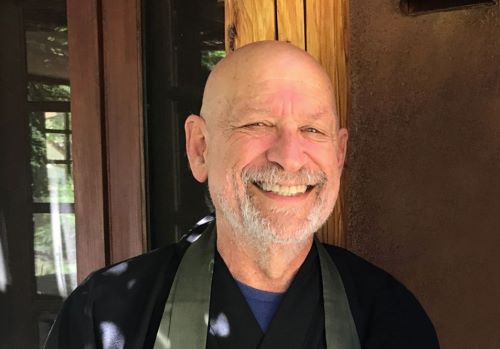

Ten years later, when his third wife – poet Shirley Graham – became pregnant, they chose to move to Canada where she had family connections going back 200 years. “So we moved to Canada at the turn of the millennium, and I was living on Salt Spring Island. It’s a small community and I had come to know many of the poets and some of the Buddhist practitioners here, but I wasn’t ready to start anything. It was clear to me after moving to the island that I was in a different culture, that Canadian culture was not New York or California, even though there was some familiarity since this was Salt Spring and there was a kind of a hippie culture available. But I’d noticed that people had different ways here – island ways, Canadian ways – and I wanted to find out where I was. So I was staying underground, so to speak, and then the September 11th attack on the World Trade Center happened in 2001.

“After the initial shock, I found myself thinking, ‘I have to do something. I can’t do nothing. There must be something I can offer to help prevent someone’s mind from conjuring things like this again’, though I was keenly aware that the attack was sadly part of the overall continuum of ignorance, hatred and violence that besets our world. So about two weeks after that, I put a piece of paper on a bulletin board in town that said, ‘Introduction to Zen practice.’ I thought, ‘The best thing I have in my toolbox as a response to 9/11 is to teach people to meditate.'”

To Peter’s surprise, 45 people showed up. There were other Buddhist groups, but no one on the island was teaching in the Zen tradition. Before long, a dedicated sangha began to form.

Things were going well, but in 2003, he realized there was something he needed to address. “I was leading a sangha now, which initially had Kwong Roshi’s authorization and support, but I no longer had a direct relationship with him or the Suzuki Roshi lineage. And this disturbed me because I’m not someone who believes you just hang up your shingle and say, ‘Hi. I’m a Zen teacher.’ I believe there needs to be relationship and accountability. But now I had none. And another concern of mine was that some people in the sangha might feel undermined by purposeful or offhand comments if we were unaffiliated. It wasn’t an issue for them, but it was for me.”

Peter discussed this with an old friend, Roshi Egyoku Nakao of ZCLA, and another close friend, Kazuaki Tanahashi, with whom Peter has published dharma books and books in translation. Tanahashi arranged a meeting with Norman Fischer, former abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center and founder of Everyday Zen.

“The meeting with Norman was warm, very intimate and good. We understood each other well, and he understood my somewhat unusual history with Zen. There was some discussion of transmission, but I said, ‘What I really would like for our sangha is an affiliation with Everyday Zen.’ And Norman said, ‘Well, if you’d like that, you and your sangha can be part of the family, but let’s keep the other conversations open.’

“We talked a little about whether or not I wanted to ordain, and I told him I was committed to a lay path, and that our sangha was a rural community of householder practitioners living on a small island, so ordination didn’t seem to fit what I thought of as our sangha’s ecology. I said that no one in our sangha had ever asked me to be a priest – if they had I’d have to consider it – but they seemed content to have me as their teacher, so it didn’t seem to hold much appeal for the real life I was living.”

“A year later, Norman wrote and said, ‘I’m going to be giving “lay entrustment” to certain people, and I would like to give that to you if you would like that.’ In the Suzuki-roshi lineage, lay entrustment authorizes householders to teach and lead sesshin as part of the lineage. So I wrote back and said, ‘Thank you. Since these are things I’m already doing, that seems appropriate for me.’ And he replied, ‘Great. We’ll begin the process, and I’ll give you entrustment. But I don’t know why you don’t want to be a priest; I really don’t understand it. The way you live and look and teach, everybody already thinks you’re a priest. But I’ll happily give you entrustment.’ It made me smile.

Peter paused in speaking and then said, “I’d like to try to explain why I wanted to stay a householder. There are two primary sources of that commitment. I started officially studying my religious tradition as a Jew when I was eight years old. It’s something I wanted very much for reasons I had no way to articulate. But I found the teachings at the synagogue pretty ‘out of the can,’ as they say. Uninspiring, institutional, and without spirit. Spiritual teachings without spirit were not what I wanted. I was hungry for something. But I took it somewhat seriously nonetheless and one day in class – I was eleven years old at the time – I said something about our tradition to the rabbi that I’d been thinking about, something that questioned a major tenet. I wasn’t being a wise guy, so I’ll just cut to the chase; when the rabbi heard what I’d been thinking he was furious, he started screaming at me and kicked me out of class. And later that night, he called and told my parents I could not come back to study. Ever.

“But my desire to learn was undiminished, so my mother asked around and found a woman in the neighbourhood, a survivor, who tutored Jewish children. So it was arranged that after school I’d go to her apartment, very dark and small, which she shared with her daughter, who must have been about nineteen years old, and she’d sit me down at the Formica kitchen table in the kitchen. And there I was given what I’d been searching for. She taught me our history; she helped me improve my reading of Hebrew. She taught me the prayers and then stood me up in a corner of the kitchen to teach me how to pray and move my body in prayer, called ‘davening’. And all of this went on in the late afternoons quite close to the stove where she seemed to always be cooking soup, stirring and tasting and adjusting the flavours as the prayers came out of her mouth. And one day, as I looked from the Formica table into the dark living room, I saw a blond wig with a long braid, which must have been her daughter’s – who I thought of as the beautiful Estelle – hanging from the doorknob to the single bedroom they shared. And beside it, hanging from the same doorknob, was a brassiere.

“Now I was eleven years old, pre-adolescenct, but not entirely naïve, so I knew that a brassiere had something to do with her daughter’s private parts, as we used to say, and the combination of that item and the blond wig made it hard for me to concentrate on the spiritual teachings I was given that day. But here’s the thing. What I l learned there, in that small, dark apartment, with wigs and brassieres on doorknobs and my female teacher – not the unforgiving male rabbi – was that the spiritual life and teachings do not need the antiseptic atmosphere of the approved institution. If you want to encounter the spiritual teachings and practices that you long for and that sustain you, you can find them in the home. And that’s a conviction that’s never left me, though I’ve loved the teaching and training and practice found within the Zen temples where I’ve practiced for half a century. I don’t think I need to make the short leap between that early realization and my commitment to Zen householder practice and life. It’s right there on the surface.”

“So that’s the first source of my commitment to living as a Buddha-householder. The second source is this: As I see it, Zen is not a two-tier deal. Either we all are Buddha or we are not. I agree with Dogen’s primary teaching on this and say that we are. There is no inherent hierarchy in that understanding, no step ladder with top and bottom. No special golden Buddhas bowing. So I wanted to demonstrate this essential teaching to my sangha to say, “You’re fine just as you are. You are Buddha. Nothing needs to be added, so even if you ordain, you are still just you, just Buddha, exactly as you are. Only practice sincerely, diligently, and well, and find out what that means, what your birthright is.” And let’s face it, as we help to establish Zen in the West, we can inherit the traditional teachings, but not the hierarchy. It’s a choice.”

Peter also points out that – with few exceptions – most ordained Zen people in the West, as in Japan, live lay lives, with houses and mortgages, jobs, families, marriages, divorce. And his commitment has inspired others along the householder path. He is one of the founders of the Lay Zen Teacher’s Association and hopes that the Suzuki-roshi lineage will eventually empower their lay entrusted teachers, among other things, to perform jukai ceremonies for their students. It hasn’t happened yet, though he sees a few promising signs despite some senior lineage priests with very strong opposition.

“After all,” he says, “as entrusted teachers, over a period of years we are the ones who train, teach, and prepare those students who want to commit to the bodhisattva path. We give them their dharma names; in my case, I inscribe, sign and seal the back of their rakusus; my name appears on their lineage papers. It just makes no sense to me that at the ceremony, after all of that, an ordained transmitted teacher must officiate even if they’ve never met the student before. The nature of the intimate student-teacher relationship, the warm hand to warm hand so important in Zen, is interrupted at this important moment by that requirement in the lineage.”

After years of discussion on this topic, Norman Fischer suggested that since Peter retained close relationships with some leaders in Maezumi Roshi’s White Plum Sangha that he bring up the subject with them. In White Plum, both ordained and householders who are accepted to train as Preceptors have the same empowerments. He talked about this with Egyoku, who was recently retired as ZCLA Abbot. After agreeing on a long path of study with her – which Peter refers to as “the most profound and focused study of Dharma” he’d ever undertaken – he received Preceptor Transmission in that lineage and was authorized to give jukai to his students.

“Some people have the mistaken impression that I have moved out of the house where I’ve practiced my whole life; the Suzuki-roshi house. They’ve talked about what they call ‘conversion.’ But that’s mistaken. I haven’t converted from one lineage or house to another. As I said to Norman, I’ve just added a room to the house, and a very important one at that.”

You had to land in a lineage with koans. All the other householder/lay entrustment stuff, lovely for canon lawyers, but you need that mysterious story line that frees and ties us to reality.

LikeLike

Love these bio-stories!

Thank you, Mark

LikeLike