Zen Center of Los Angeles –

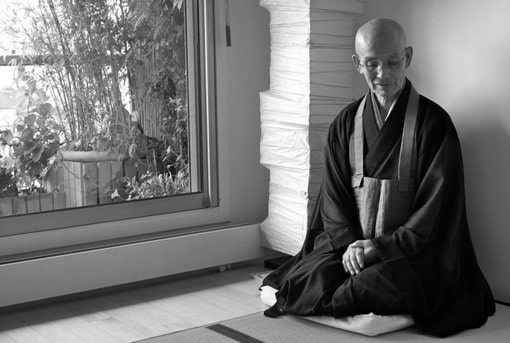

Wendy Egyoku Nakao – abbot emeritus of the Zen Center of Los Angeles – invites me to call her Wendy which, she explains, is easier to pronounce than her Dharma name. It is a light-hearted conversation. She laughs easily and frequently.

She was born and raised in Hawaii. “My father was Japanese; my mother was Portuguese. I grew up on the Big Island in a village called Mountain View. My mother was Catholic. She came from, I would say, a typical Portuguese Catholic family, but when she married my Japanese father, it caused dissension, and she was basically kicked out of the family. I sensed that her religious practice, such as it may have been, went underground. My father had no use for religion until late in life. His father became a Tenrikyo priest, one of the new religions of Japan founded by a shamanist in a dried-up creek. His father—my paternal grandfather— left a small Tenrikyo temple to his wife, my father’s stepmother, and she kept it going.”

“And this was a place your father visited?”

“He visited often when my mother became ill. He arranged for the priest and his wife to come to our home every day to bless my mother. The priests’s wife and her small children walked two miles to bless her every single day for many years. But we didn’t have any religious upbringing to speak of. Whenever I brought forms home from school that asked what our religion was, my mother would write something different each time! But even as a child, I kept wondering, ‘What is the meaning of all this?’ From when I was very little, I had that burning question. I always wanted to go to church, but nobody had time to take me.”

She left Hawaii to go to college, enrolling briefly at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma then transferring to the University of Washington in Seattle. One summer, she enrolled in a course on Japanese architecture. The class instructor was Professor Glen Webb, who also hosted a Zen sitting group.

“And around mid-summer, he announced to the class that a Zen master was coming from Japan to hold a week-long sesshin. I thought, ‘Wow, that sounds interesting,’ And after class, I asked Professor Webb if I could take part in whatever it was, and he said, ‘Sure.’ I asked what happens, and he said, ‘We meditate, and we don’t talk for a week.’ I went home, and I told my husband of the time and his best friend, who was visiting, about it. I said, ‘I heard about this retreat where you don’t move, and you don’t talk for, like, a whole week!’ And our friend said, ‘I bet you fifty bucks you can’t do that.’ And I said, ‘You’re on.’ That’s how I ended up going to my first sesshin.”

“Did you ever get the fifty bucks?” I ask.

“No, I never did.”

“Did you earn it?”

“Did I earn it!” she says laughing. “I went off to Vashon Island where we were in this little Baptist retreat center, and I don’t know how many of us there were. Maybe fifteen? Some people knew about sitting, but I didn’t know a thing. Glen Webb was the translator, and this teacher only spoke Japanese.”

The teacher was Katsufumi Hirano.

“Anyway, this sesshin! The periods were fifty minutes! The bell rang. You undid your legs. You folded them back for another fifty minutes. We did twenty minutes of walking meditation after lunch. It was torture! It was so tough! I didn’t know a thing; I don’t remember being given any instruction. And in the middle of these torturous periods, in real Soto style, the roshi would start talking about Dogen Zenji who I’d never heard of, and then it would be translated, and we’re sitting there, just suffering. I was seated between two guys. One was an engineering student from Japan who had never sat in his life; the other was an old hippie from Canada. We had so much fun! I started laughing a lot, all the energy that was bottled up in me started to release.

“But during the week, I had a really important realization, unfortunately for my husband and my whole family. While I was sitting there, I had a powerful vision of myself twenty-years hence on a couch having a complete nervous breakdown if I continued the life I was currently living. I said to myself, ‘I’m not going down that road.’ I didn’t know what else was available to me, but I was not going to go there. Something ignited within me, something woke up in me, a longing that had been in me since I was a kid. It was such a force, and I had to follow it. I went home from that retreat, and I told my husband, ‘I’m so sorry, but I have to leave you.’ Which is why I never got the fifty bucks!”

“What made you think you’d have a nervous breakdown if you kept living as you were?” I ask.

“Because I was not living the life I needed to be living. It was too constricted. Having grown up in this really hardworking working-class family in that small village, the only future we knew of was ‘get married and have a family’ or get a job. Nothing else seemed to be available, although some of my teachers implied that there was something more.”

Katsufumi returned to Japan, but Wendy remained with Webb’s sitting group and attended other sesshin with him. Then a co-worker showed her a poster from the Zen Center of Los Angles. “It said, ‘Zen living ain’t easy.’ It was advertising a year-round training program. And he said to me, ‘You should consider this. This looks like something you’d be interested in.’ So I applied for a sabbatical which I was given to go to a Zen Center for six months. That was in 1978.”

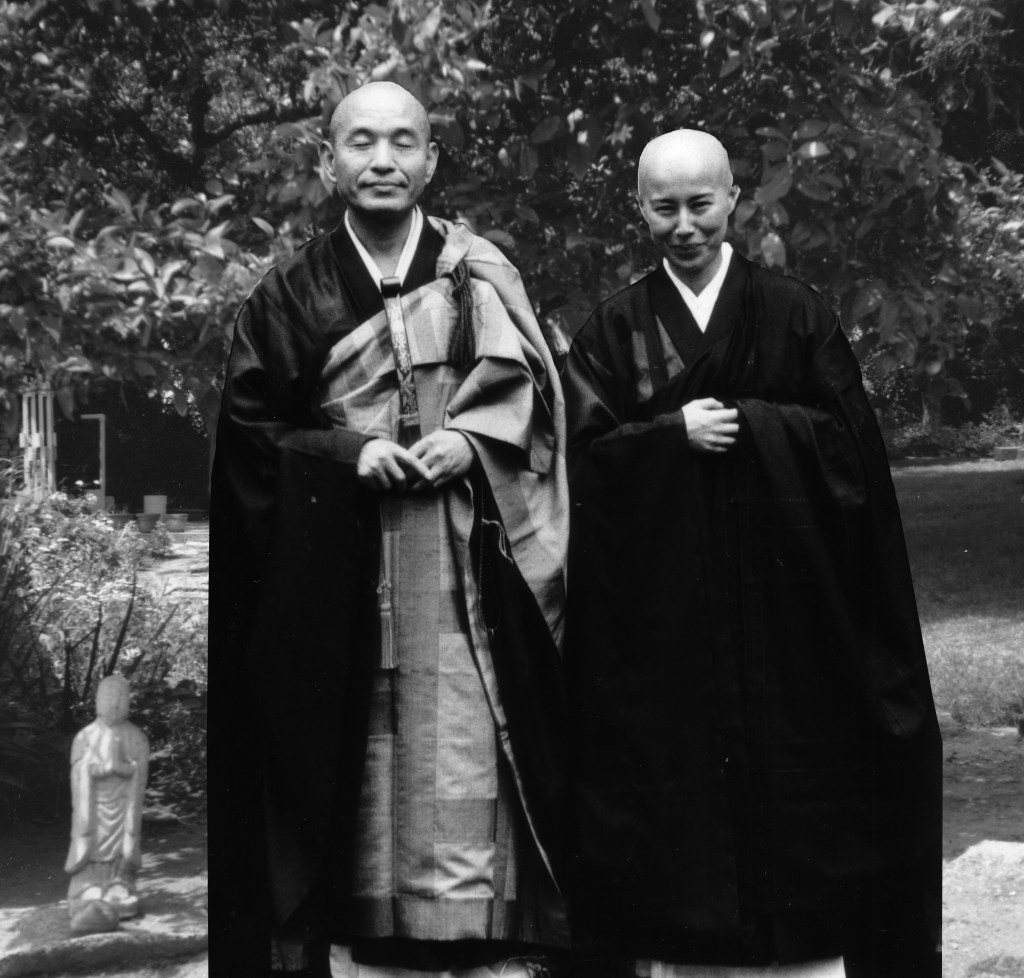

The center was led by Taizan Maezumi Roshi and his senior Dharma heir, Bernie Glassman, who had just received transmission.

“I did a deep dive. At that time the training schedule was 24/7; I loved it. My energies could match that, so I just plunged into the sitting and the entire schedule. After six months, I had to return to work. I returned and then resigned my position. The Zen Center asked me if I wanted to come back and be on staff to set up their library, and I said, ‘Sure.’ I went back and forth between Seattle and Los Angeles for a while, and then I realized, ‘You know, I’m just going to move to Los Angeles.’ And so I did.”

“What was the draw?”

“I don’t know what to tell you. It met some longing in me – right? – to really go deeply into who I was and what life was about. It just did that. I couldn’t have articulated it at the moment, but it did. It felt right, and it felt like I needed to do this. This was a place where that could happen.”

“And did it?”

“Yeah. I would say so. I mean, after all, I was there for over forty years! You know, I have just left ZCLA after pretty much having to bring it back to life and everything . . . And I really did that out of an obligation to my teachers, particularly Maezumi Roshi.”

She’s not over-stating this. She did bring it back to life after a series of calamities that began in 1983, when Maezumi admitted that he was an alcoholic and that he had been in sexual relations with certain of his students. He broke the relationships off and went into a treatment program for alcoholics, after which he apparently stopped drinking, at least publicly. There were people who suspected he continued to do so privately. His admission, however, resulted in many people abandoning ZCLA. The center was still in the process of rebuilding when, in 1995, Maezumi died during a visit to Japan. When ZCLA was informed, they were told he’d had a heart attack in his sleep. Wendy at that point was Maezumi’s assistant. She and Bernie Glassman – who was in New York establishing his own Zen community – went to Japan for the funeral ceremonies, then came back to LA to deal with the situation there.

“Bernie and I made about five trips to Japan that summer to plan the memorial service in Los Angeles, which was scheduled for the end of August. Bernie inherited, through Maezumi Roshi’s will, all of ZCLA, which included Zen Mountain Center at that time. This poor man. He already had the Greyston Foundation in New York. Now he had to work with ZCLA, the Zen Mountain Center, the White Plum Asanga, and the Soto Shu to name a few things. But mostly we were focused on the Memorial Service.”

I asked who was in charge in LA after Maezumi Roshi’s death.

“I don’t recall who was on-site. Most of Maezumi Roshi’s successors were already engaged in their own centers. Bernie asked me if I would take it on, and I declined. One of Maezumi Roshi’s successors finally stepped forward to do it knowing he was not particularly suited for that kind of thing. ZCLA was such a complex scene. This person became the resident teacher, and Bernie was the abbot. Bernie had to figure out what was happening at these Centers and who the people were; it was a major transition.”

The person she is referring to was William Nyogen Yeo,

Wendy herself moved to New York to continue her training with Glassman and to assist Bernie with Maezumi Roshi’s legacy. And then the community was hit with another trauma.

“There was another scandal,” she tells me. “Bernie would say to me, ‘I’m waiting for the other shoe to drop.’ And I would say, ‘What shoe?’ And he said that at times of major transitions, something usually happens to further change the course of things. Of course, it was the usual drinking and sex scandal. The Zen Center blew up again. I wasn’t there; I did not want to be dragged into the mess. Bernie and other senior teachers did their best to attend to it. The teacher left, and the sangha was in upheaval. Bernie asked if I would consider returning to ‘heal the Sangha.’ He was reluctant to ask because he knew that I had other plans. While I was hemming and hawing, some people called me from ZCLA and said, ‘Don’t come back. It’s really bad here. Don’t put yourself through this.’ But in the end, I thought, ‘I owe it to Maezumi Roshi, and I owe it to Bernie to at least try.’ And so I did.

“I remember the day I returned, April 15, 1997, ‘to heal the Sangha.’ Interestingly, at this time in New York, we were forming what would become the Zen Peacemakers. Bernie was starting to articulate a more contemporary way of Zen training, including the Three Tenets of Not knowing, Bearing Witness, and Taking Action. We were also experimenting with different community frameworks instead of the top-down Zen model. All of this ended up serving me and ZCLA very well because it was ripe for a complete reinvention of itself. So I returned for three months with Bernie’s support to try whatever I thought best to settle the Sangha. I did things that cut into the structure most communities have, because we had to figure out a different way of being together. I listened deeply to what was there and what was arising. Bernie often said that I was doing the three tenets long before we called it that.

“Anyway, I extended my stay three more months, and then I ended up staying for twenty-two years. There was a lot to navigate through, but my emphasis was ‘to take care of the people,’ as Maezumi Roshi had often encouraged me to do. After the former teacher’s students had left, I had more space to assess the situation. I invited those remaining, ‘If any of you still feel you cannot move forward from what happened and what you’ve been through, let’s come together in a circle.’ Twelve people came. I started a process with them which I made up as I went along. We ended up calling it the Healing Circle Process, which incorporated the not knowing, then bearing witness, then taking action in a continuous practice framework.

“We committed to being together until our process – whatever it was going to be – was complete. The first step was for each member of the circle to tell their story, their experience of what happened to them during this upheaval. I said, ‘You have to tell it so that you never have to speak of it again. I want you to be that complete, that thorough.’ I didn’t want this continuing recycling of the story, so I said, ‘Get it all out.’ Each person took about an hour and a half to tell their story. The rest of us just listened, and by the second story, everyone realized that each person’s experience and point of view were quite different with some similarities. Most of it came down to feeling it was something like a family divorce or, ‘Somebody abandoned me,’ or an early parental death. We went pretty deep and compiled all the ingredients, uncovering many aspects of the situation. An ingredient was anything from an emotion to your opinion about Zen training and its teachers, and so forth. Each person then chose their primary ingredient. They worked in pairs and groups, deeply investigating the ingredient, like a koan. Then, each person presented that to the group. This led to an action by each person. We had a closing ritual, and then the process was complete. We had moved to a different space and could now move on. It took a lot of patience, commitment, and work. I learned a lot about what their experiences had been since I wasn’t present for that whole upheaval.

“Sometime after that, I decided to commit to being the resident teacher. After two years, I succeeded Bernie as the abbot, a position he had held for four years. By then, I realized that ZCLA was, ‘Beyond band aids.’ I had this insight, ‘We need to let it all collapse. Then let’s see what is wanting to be born anew here.’ ZCLA had very deep and strong roots in the Dharma but no structure to support its transformation. So we cleaned house, the buildings, grounds, and decades of accumulation of stuff. Then after I had been abbot for about two years – listening and discerning – it was time to seriously think about what we were going to create at ZCLA, what was wanting to come into being.”

She decided that membership would do a year-long course on what came to be called Shared Stewardship.

“Our explorations morphed into a new way of being together as a Zen community. The class ran for one year, one Sunday a month for four hours and meetings in between by groups who took on developing various aspects of ZCLA. The class was an open invitation to whoever was interested in developing a new Zen culture and center. We had 45 people commit to the year-long endeavor. I’d never led anything with 45 people! Our first meeting was so chaotic! It was just a hoot. I described the framework of the Zen Center as it was understood at the time. One of the big issues was our financial survival. It was a chaotic time. It was a lot of fun, too.” She’s laughing as she describes this to me. “When I think about it now, I chuckle at how my determination to honor Maezumi Roshi’s vow caused me to muster the courage to confront all our problems, and I am in awe of people’s openness to experiment.

“I realized after the first class that each person had a different view about what the Zen Center was, what it was founded for, what its history was, and so forth. We were all over the place. Some people had been there from almost the beginning; others had come when Maezumi Roshi died; still others had just walked in through the door. I decided to tell the story of ZCLA, starting with Maezumi Roshi’s family, him getting on the ship, coming here, as much as I could recreate for everybody. It took about five months, about twenty hours to tell that story. Then we get to the scandal of ’83. It just so happened that there was a film about it.”

A film crew had been scheduled to do a documentary[1] at ZCLA just before Maezumi went into rehab. The membership of the center was still struggling with the revelations of his infidelity to his wife, and his sexual involvements, and, when the crew arrived, many of the residents wanted to cancel the project. Maezumi, however, insisted that the film makers be allowed to do their work and that nothing should be concealed from them. At the time Wendy was running her year-long reflection, she still hadn’t seen the film. But she found a copy, and she showed it to her group.

“It was so interesting because here’s what people were excited about: They said, ‘If we can put this on the table, we can talk about anything.’ Then we came to Maezumi Roshi’s death. I realized I didn’t know who knew what about it. So I told them the story, but, before I did that, I spoke to the senior people who knew him well, not having any idea about what they knew.”

I had been told this story before. “My understanding is that you were gathering documents for insurance purposes,” I said, “and that’s how the actual details of his death became known.”

“I needed his death certificate. Bernie and I were in Japan during the summer after Maezumi Roshi’s death, working on the upcoming memorial. On one trip, I told one of Maezumi Roshi’s brothers, ‘I really need his death certificate because there’s insurance money for the family, and we need to have it.’ He was not forthcoming. One day, he, Bernie, and I were in a small Japanese taxi on our way to visit a Roshi, I forget who it was. Suddenly, Maezumi Roshi’s brother, who was seated next to the cabdriver turned around and said, ‘Oh, I have Maezumi Roshi’s death certificate.’ Just like that. I said, ‘Oh, great. And how did he die?’ And he said, ‘Word very difficult.’ And I said, ‘Difficult? What word?’ And he said, ‘Maezumi Roshi drowned.’”

He has been intoxicated while visiting a brother and died in the family bath.

“I leaned over to Bernie in the cab, and I asked, ‘Does this mean he didn’t die of a heart attack?’ Bernie said, ‘That’s what he just told you.’ So then we did the visit, and then we went to Soto Headquarters to have this lo-o-ong meeting. I could not focus. Everybody could see that my mind was elsewhere. Bernie kept looking at me with one eye, like, ‘Are you okay?’ And finally, late in the evening, we returned to our hotel. We haven’t had a chance to talk about it at all. Bernie says, ‘How about we have some ice cream?’ They had really good ice cream parfaits at this place,” she says with a laugh. “We’re not saying anything. We order the parfaits. The parfaits come. I looked at Bernie. I said, ‘Oh, my God, Bernie. He fucking drowned? What is that about?’”

“So now you have to inform the community,” I say. “You’ve watched the film; you’ve done the history. Now you have to tell them about the manner of his death.”

“I told the story as I’d experienced it. The senior ZCLA people knew. There was just one person who got so upset he left. And that was it. Everybody else rolled with it. Some people were shocked; some had wondered about his death, but life had gone on in the midst of all that grief.”

“And once you got through all this, how did the community change?”

“It changed a lot; the hierarchy is no longer the dominant structure. We spend time developing the horizontal structure, the Sangha. We create the mandala of the Zen Center based on the Five Buddha Families as expounded in the Gate of Sweet Nectar ritual for feeding the hungry spirits, so that all the components that go into making a Zen Center are known by all. Everyone gets to learn all the different components. Circles are formed to attend to the different sections of ZCLA.”

I ask her what distinction she sees between a circle and a committee.

“It’s a completely different way of thinking about things. For me, the word ‘committee’ is a dead word. It has no energy. A Circle is inclusive of all the energies. A Circle invites in all the voices; the facilitation rotates. Each circle creates its own mission-vision and creates a way to be together as a Circle. They carry out their tasks, but always at the core is how they are honoring their relationship with each other. The practice of Council is interwoven in Circles.”

I mention that when I had interviewed Chozen Bays, she had described ZCLA during the time she was there as a combination of “Zen monastery and hippie commune.”

Wendy laughs again. “I never considered myself a hippie, but there’s no question that the early years were often characterized as part kibbutz, part hippie commune, part monastery, a community with an electric teacher at the helm. The Japanese monastic structure met the openness and free expression of American culture at that time. Maezumi Roshi would always say, ‘I don’t understand Americans. How it evolves is in your hands going forward.’ There wasn’t time in the years that he lived to evolve the Sangha. He wasn’t the person to do it, and he didn’t have that inclination. He knew that things were not working well, but it wasn’t his work to evolve the sangha treasure.”

“But that was your job?” I suggest.

“To build the sangha treasure, to promote the practice of the flourishing of wisdom and compassion. And to address the many shadows of the community, which called forth new upayas and, after many years, also resulted in ‘The Sangha Sutra.’” The “Sangha Sutra” is a fifty-page document outlining Ethical Procedures at ZCLA.

“And what is the function – the purpose – of the community that came about as a result of all this work?” I ask.

“I think the function of community is to make sure that we are all truly embodying the Dharma in service to others. Sangha is the third of the Three Treasures; it’s what gives life to Buddha and Dharma. Community should make each of us a better person. It’s hard to live a human life. Community can make us stretch beyond what we imagine are our limitations, to learn how we are interwoven, and to be exposed to and include differences, and to help each other.

“I also came to believe there is a fourth Treasure as well, the entity of the Zen Center itself. How does one administer, operate, run, function in the mode of Dharma? We’re a capitalist society; we could take any business model and operate that way. But when Zen Centers keep imploding, we had to inquire deeply about what we are doing. Can we create a structure of living Dharma, of people who come together to wake up, and of an organization that continually and consciously strives from a place of understanding and practice of Dharma? This has to be articulated very explicitly; we can’t assume that we’re all on the same page. The situation invited us to examine and articulate our core values as a Buddhist sangha and as an organization and how we would live those values. How does the Dharma speak to these things? What does it look like when we’re actually coming from that place? And can somebody feel that when they walk through the temple gate? Can they sense that there’s something different going on here. I think it’s very nuanced and it’s very subtle, and it’s very real and alive.”

“Okay, let’s consider that person who comes through the gate,” I suggest. “What usually brings them?”

“All different motivations, but I think that, at the bottomless bottom, there is a longing to know something, to fulfill something. To live differently. To make sense of their lives. To understand what they’re doing on the Earth.”

“And how does this practice help them address that longing?”

“The practice penetrates to the core, to ‘non-,’ to Mu, and the sangha becomes a place to experiment and support each other’s transformation. Practice is a crucible, alive and demanding. We have the capacity to go to the core, have that open up for us and, along the way, clarify what it is we need to work on to come into our wholeness.”

“Okay. I have a sense of longing. That draws me to check out the Zen Center in Los Angeles. I suppose that when I arrive one of the first things that happens is you introduce me to a technique.”

“First, we say hello!” she laughs. “Then I might ask you what your aspiration is. Of course, you’re shown how to sit.”

“Do I work with a teacher individually?”

“If you wish.”

“There are people who prefer not to?”

“Some people don’t take to the one-to-one format.”

“And if I’m not keen on one-to-one interaction with a teacher, then it’s the community that comes to the fore?”

“The community – the Sangha – is your greatest teacher. It’s the testing ground.”

“So the emphasis is less on one coming to ZCLA to do something than it is to take part in a community. Is that overstating it?”

“Working one-to-one with a teacher is very important, but you’re also learning how to live with other people. There are many different ways a person can participate in ZCLA. The community is structured as an upaya – a skillful means. The teachers offer one-on-one, face-to-face. I’ve taken many students through koan training and still do. All of that is still going on. The rituals are going on, the rites of passages. There are many, many facets—many upayas— that are happening.”

I suggest that the Center, as it exists now, is part of her personal legacy, and she agrees.

“So,” I say, “now that you are stepping back, what is it that you hope for them?”

“My hope is that they keep waking up, deepening and expanding. Keep deepening and expanding into the Three Treasures. The world needs these places where people penetrate into and live out the wholesomeness of life. The whole of life, nothing excluded, knowing oneself as the intersection of all. We need places where people are examining this, where they’re willing to spend time experiencing and being a voice for this kind of stillness in the midst of life.”

“You used the term ‘wholesomeness.’ And I agree, personally, that that is pretty central to what Zen practice is all about. But there’s lots of examples – we’ve talked about some of them – where that wholesomeness hasn’t always been manifested by people who hold positions of authority in the community. How is it that there’s been so much unwholesome behavior?”

“How can there not be? Wholesomeness is not just the good bits. It’s all, the wholeness, of the human condition. We’re including all of who we are, including the ‘unwholesome,’ the unevolved. This is why I think we need to create the sangha skillfully so that our unwholesomeness is exposed, and we can welcome and work with it as the ingredients of our practice. I’ve sat with many communities that have imploded, not just my own. They don’t have a sangha net to hold anything because no one’s ever paid attention to it. And I just know when I sit in one of these communities that they’re not going to make it because they haven’t put in the time to weave something that they can trust. They don’t have the imagination that this could be possible. They don’t hold together. They split into smithereens. And it’s really so painful to watch over and over. It’s too oriented to the teacher. The teacher is important, but the sangha is also a teacher. There are Three Treasures after all.” Then she adds, with a smile, “Well, Four by my count.”

<

div dir=”ltr”>Rick,

<

div>Each of your postings give me a litt

LikeLike