Adapted from The Third Step East –

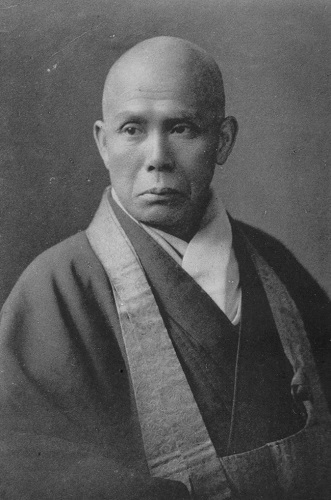

When telling me about Shunryu Suzuki’s arrival in the United States, David Chadwick pointed out that Suzuki “landed in the middle of the Alan Watts Zen boom.” Two men, in particular, can be credited with preparing the way for the extraordinary success of early Zen teachers like Suzuki and Philip Kapleau. The first was another Suzuki – Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki – and the other was his popularizer, Alan Watts.

Teitaro Suzuki was born in 1870 in what is now the Ishikawa Prefecture. His family was of the Samurai class, which—prior to the Meiji Era—had held a privileged position in feudal Japan. After the Meiji reforms, however, most of those privileges were lost.

His father died when Teitaro was only six years old, leaving the family in poverty. A year later, his older brother also passed away. At an early age, he wondered why he had had to face so many difficulties and challenges in his life—the loss of family status, the deaths of his father and brother, the family’s straitened financial circumstances.

Fiscal constraint prevented him from completing secondary school, but he was able to find work teaching English at a primary school in a nearby fishing village. The Suzuki family recognized Teitaro’s academic talents, and, after their mother died in 1890, his older brother provided him funds to attend Waseda University in Tokyo. This put him close to Kamakura where Engakuji – one of the primary Zen temples in Japan – was located. Still preoccupied by the concerns that had haunted him as a child, he determined to visit Engakuji, where the abbot, Imakita Kosen, accepted him as a lay student.

Kosen assigned him Hakuin’s koan, “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” Suzuki found it entirely opaque. When he went to sanzen with Kosen, the teacher would put his left hand forward without saying anything, and Suzuki had no idea how to respond. Whenever he attempted to express his thoughts about the koan, Kosen dismissed these as nothing more than ideas.

Within a year, Kosen died. His heir, Soyen Shaku, changed Suzuki’s koan to Mu. Suzuki applied himself to the new koan with all his energy, feeling as if his life would be meaningless if he were unable to resolve it.

When Shaku learned that his student was able to read and write English, he assigned him a number of translation tasks, including his correspondence with the organizing committee of the World Parliament of Religions. He also had Suzuki translate Paul Carus’s The Gospel of Buddhism, for which Shaku had provided an introduction. Throughout all of this work, Mu remained at the back of Suzuki’s mind, but he came no closer to understanding it. Because he had nothing to say, he stopped attending sanzen with Shaku, except those mandated during the formal retreats, and, on those occasions, Shaku often dismissed him with a blow.

This continued for four years. Suzuki wondered if his difficulty was due to a lack of familiarity with Zen literature; perhaps, he thought, he could find the answer to Mu in one of the books in the Temple library. He immersed himself in these, which would be a great help to him when he later began writing, but nothing he read helped him understand Mu any better.

When, after the 1893 World Parliament of Religions, Paul Carus asked Soyen Shaku to consider remaining in the United States to assist him in preparing translations of Eastern texts, Shaku suggested that Teitaro Suzuki would be better suited for the position. In a letter to Carus, Shaku described the future scholar as an “honest and diligent Buddhist” but also noted that he was “not thoroughly versed with Buddhist literature.”

It was a great opportunity, but Suzuki was aware that going to the United States also meant that he might not be able to partake in sesshin for many years. If he did not resolve the koan during the upcoming sesshin, he would not have another opportunity until he returned to Japan, and he had no idea when that would be.

The next sesshin was the December Rohatsu Sesshin which marks the anniversary of the Buddha’s awakening. Traditionally, it is the most demanding retreat of the year. Suzuki concentrated on Mu, synchronizing it with his breath. By the final days of the seven-day retreat, the koan was no longer something separate from him. There was not the koan on the one hand, and the person repeating it on the other; there was only Mu.

Then, after a round of meditation, he was roused from his concentration by the sound of a bell being rung, and Mu was resolved. This was the “satori” – or awakening to one’s true nature – about which Suzuki would write so tantalizingly in the future. Suzuki rushed to sanzen and was able to answer all but one of the testing questions Shaku put to him; the next morning, he was able to answer that question as well. Shaku acknowledged the validity of his awakening and gave him the Buddhist name “Daisetz” which means “Great Simplicity.” Suzuki retained the name for the rest of his life, joking that it actually meant “Great Stupidity.”

He arrived in San Francisco in 1897 and was welcomed to the United States by being placed in quarantine on the suspicion that he had tuberculosis. After a period of observation, as well as interventions on his behalf by Carus, he was allowed to proceed to Carus’s home in Illinois.

Carus was one of a number of thinkers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries who were trying to reconcile the growing conflict between religion and science. He sought to identify what he called a “Religion of Science,” a religious perspective shorn of mythology and superstition, in harmony with current scientific understanding, which could be globally accepted. He believed that Buddhism had the potential to fill this role. To that end, his Open Court Publishing made Eastern texts available to the West. Suzuki would work with Carus on this project for eleven years.

His first assignment was to assist with a translation of the Tao Te Ching. Suzuki was not happy with the rendition, believing that Carus distorted the work by his use of abstract Western terminology which didn’t adequately reflect the intention of the text. Suzuki also took it upon himself to translate Ashvaghosha’s Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana, which would be the first of many books in English that he would release under his own name. This was published in 1900, after which Suzuki began work on Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism, in which he sought to counter the perception of western scholars who viewed the Mahayana – with its esoteric teachings and plethora of Bodhisattvas – as a degenerate form of Buddhism when compared with the older Theravada School.

There was growing academic and popular interest in Buddhism after the World Parliament of Religions, although the number of Westerners who gave serious thought to adopting the Buddhist faith was miniscule. There were a few, however, some of whom even found their way to Engakuji and undertook Zen training under Shaku’s tutelage. In 1905, one of these, Ida Russell – a resident of San Francisco – and her husband invited Shaku to make a second visit to the United States as their guest.

Shaku accepted the invitation and arranged for Suzuki to meet him in California. Arrangements were made for Shaku to give a number of talks to the immigrant Japanese communities in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sacramento and Oakland. Then in 1906, attended by Suzuki, he proceeded across the country by train. During his tour, Shaku met a range of political and academic figures, including President Theodore Roosevelt, and he gave public lectures on Zen. Like Suzuki in his Outline of Mahayana Buddhism, Shaku sought to correct popular misconceptions. Christian critics had been vociferous in condemning Buddhism as a negative and life-denying doctrine the goal of which was the total extinction of the person in Nirvana. Shaku argued instead that Buddhism was life-affirming, and that through meditation practice the individual came into direct contact with “the most concrete and withal the most universal fact of life.”

Shaku’s tour lasted nine months, and, while they were in New York, Suzuki met Beatrice Erskine, whom he would later marry. When Soyen Shaku returned to Japan, Suzuki resumed his work with Carus and remained in Illinois for another two years.

In 1908, he left Open House Publishing, went to New York, and renewed his acquaintance with Beatrice. Then he did a tour of Europe before returning to Japan, where Beatrice would eventually follow him.

They were married in Yokohama in 1911 and adopted a son, Paul, who was of mixed European and Japanese descent. Both their marriage and the adoption flouted the ethnocentric attitudes common throughout Japan. The family lived in a small cottage in the Engakuji compound until 1919, when they moved to Kyoto, where Suzuki taught at Otani University.

They founded the Eastern Buddhist Society and published an English language journal, The Eastern Buddhist, to which they both frequently contributed articles. A number of D. T. Suzuki’s pieces were collected and published by the British company, Rider, in 1927 under the title, Essays in Zen Buddhism. The book related Tang dynasty koans and tales never before heard in the west and was surprisingly successful. More than any other work to that date, it would be responsible for promoting a popular interest in Zen both in North America and Europe.

Suzuki was 57 when Essays in Zen Buddhism was released; his output after its publication was prodigious. A second and third volume of Essays were brought out by Rider. He released a translation of the Lankavatara Sutra in 1932; The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk was published in 1934; and Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture came out in 1938, the same year that Beatrice published Mahayana Buddhism.

The appeal of Suzuki’s books was the portrait he gave of a religion which stood in stark contrast to the Judaeo-Christian heritage of the West—a religion without a deity, a religion which held that the practitioner could attain the same insight and awareness its founder had had. In response to those critics who viewed the Mahayana as a distortion of the Buddha’s original teaching, Suzuki insisted that a vital religion must not be limited to its earliest expression but must demonstrate the ability to evolve. Zen, he argued, was Buddhism “shorn of its Indian garb,” the cultural and historical trappings of the original teaching. What was central to Zen, after all, was not a “dependence on words and letters” but the transmission of the original awakening experience by which Siddhartha Gautama became the Buddha and which he passed onto his disciple, Mahakasyapa.

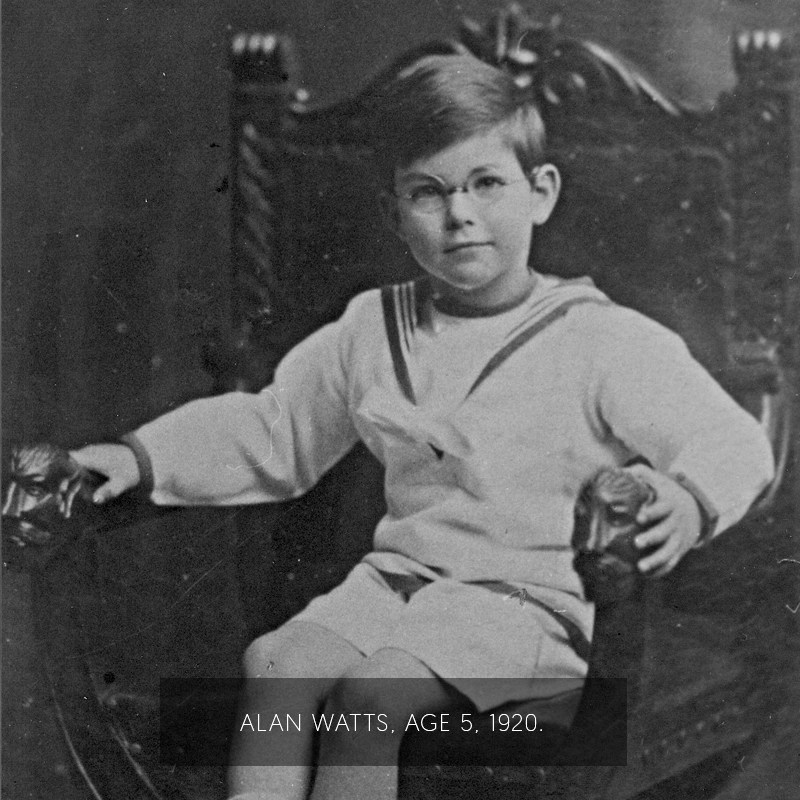

Alan Wilson Watts was born during the First World War in the English village of Chislehurst in Kent. His mother, Emily, came from a staunch Evangelical Protestant family. She was loving but strict and was the family disciplinarian. Watts’ father, Lawrence, on the other hand, was more gentle and tolerant. Emily had been raised to believe that human life was a testing ground during which it was determined whether one was worthy of salvation or was to be condemned to eternal damnation, and she was as concerned about her only child’s spiritual well-being as she was his physical. Religious instruction took place in a gloomy, unheated second-floor bathroom. In this bleak environment Watts’ nanny read him Bible stories, and his mother taught him his first prayers and spanked him when she deemed it necessary. It was also the room where he was quizzed every morning about the state of his bowel movements. He hated the room.

In contrast to the disagreeable bathroom was the first floor Sitting Room, reserved for use on special occasions only. Before she was married, Emily had taught at a school for the daughters of missionaries to foreign lands, and, in the Sitting Room, she kept exotic presents given her by the families of those girls: Chinese and Korean vases, a Japanese tapestry and cushions, and a brass coffee table from India. Here Watts first acquired his love for the mystique of the Orient.

Watts suffered through the brutalities of the British boarding school system, where he received what he later described as a “Brahmin’s education.” The preparatory school to which he was sent was expensive, and his parents had to struggle to make the fees, but they were willing to do so in order to ensure their son received the type of education they believed would serve him well in the future. The all-male boarding school, however, was not the type of environment for which Watts was suited; among other things, even as a young boy he preferred the company of girls and women. The curriculum focused on the history of the British Empire, militarism, and low church theology. Watts sought escape from the dreariness of this course of study by reading the novels of Sax Rohmer, in which he identified more with the Asian villains, like Dr. Fu Manchu, than with the square-jawed British heroes, such as Nayland Smith.

He decorated his room at home with the type of inexpensive Asian ornaments a schoolboy could afford, including a small reproduction of the Kamakura Daibutsu. Eventually his mother—who had good taste in such matters—supplemented these with better pieces, as well as presenting him with a copy of the New Testament written in Chinese, which roused a lifelong interest in Chinese calligraphy. Once more—as in the contrast between the awful bathroom where Bible stories were told and the Sitting Room—the brightly colored exotica of the Orient provided an alternative to the drabness of all things British and Protestant.

He was intellectually gifted and earned a scholarship to King’s College in Canterbury, a public (that is to say, private) school to which otherwise his parents would not have been able to send him. The rich history of Canterbury, its elaborate Gothic architecture, and the pageantry of High Church Anglicanism provided a more stimulating environment for Watts than his preparatory school had. On the other hand, he was well aware that he was not of the same class as the majority of his fellow students. In order to counter a bourgeoning sense of social inferiority, he developed a persona which allowed him to feel intellectually superior to his classmates.

He may not have belonged to the gentility, but his tastes ran in that direction. He was precocious enough, while still a teen, to be able to cultivate adult friendships which permitted him to share in a lifestyle beyond his family’s reach. His appreciation of Asian art and aesthetics led him to search for books on Japan and China. One of his adult friends loaned him a number of these, including a pamphlet by Christmas Humphreys, then President of the Buddhist Lodge in London. In the overview of Buddhism provided by Humphreys, Watts found a view of life which struck him as more reasonable than Christianity, so, at the age of 15, he boldly announced to his classmates that he was a Buddhist. He also initiated a correspondence with Humphreys in which he expressed himself so maturely that Humphreys assumed the writer from King’s College was a member of staff and was surprised to discover, when Watts attended his first Lodge meeting during the holidays, that his correspondent was in fact a sixth form student.

Humphreys was the type of adult Watts admired and sought to befriend, wealthy and sophisticated, a barrister who was to become a well-respected judge. Humphreys and his wife, who were childless, admired the young Watts and came to look upon him almost as a son. Watts’ actual parents, perhaps hoping his interest in Buddhism was a youthful enthusiasm he would outgrow, supported his inquiries and even attended Lodge meetings with him. Lawrence eventually became a Buddhist. Emily remained reserved, noting that Humphreys ran Lodge meetings much like a Sunday School class. It was Humphreys who introduced Watts to the books of D. T. Suzuki.

As head boy of his house at King’s College, Watts had the freedom to use an Elizabethan room after hours where he experimented with meditation guided by his reading, although he was not clear about what the writers meant by satori, moksha, samadhi, or enlightenment. He was considering this problem in the fall of 1932. In his autobiography, he wrote, “The different ideas of it which I had in mind seemed to be approaching me like little dogs wanting to be petted, and suddenly I shouted at all of them to go away. I annihilated and bawled out every theory and concept of what should be my properly spiritual state of mind, or of what should be meant by ME. And instantly my weight vanished. I owned nothing. All hang-ups disappeared.”

Watts’ masters at King’s College—and his relatives—felt that he should easily be able to earn a scholarship to Oxford, but he did poorly on the entrance examination, and the scholarship did not materialize. Once he completed public school, his formal education came to an end. His prospects were not good, and he was fortunate to have the friendship of Humphreys at a time when his mother’s family, in particular, let him know how disappointed they were with him. Without a university degree, the professions were closed to him, and it was not clear how he was going to support himself financially.

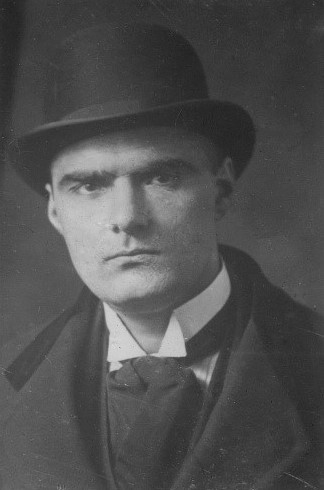

With Humphreys’ guidance, he continued his independent studies. He met a number of people who shared his interest in esoteric religions and the occult, among whom was Dmitrije Mitrinovic, who was rumored to practice black magic. Mitrinovic introduced him to the study of psychology, which would remain one of his abiding interests. He also read the Upanishads, the Diamond Sutra, and the Daodejing. Humphreys—whose Buddhism was liberally laced with Theosophy—introduced him to Blavatsky, but their greatest shared interest remained Suzuki whose works they continued to study and discuss.

Lawrence was able to help his son get employment at the foundation where he worked raising funds for London hospitals. The job was not difficult, and it gave Watts – still only 19 – time in the evening to work on an attempt to clarify Suzuki’s writings. At the end of a month of effort in 1935, he had a manuscript entitled The Spirit of Zen. Humphreys contributed a foreword, and the book was released by John Murray the following year.

It was a small work, less than 40,000 words, which was essentially a reader’s guide to Suzuki, but it already demonstrated a skill which Watts would hone throughout his life of being able to describe spiritual issues in a clear and intriguing manner.

The year after The Spirit of Zen came out, Watts met Suzuki, who was in London to attend the World Congress of Faith and, as the guest of the Buddhist Lodge, greatly impressed his hosts. In Suzuki, they found someone who not only understood Zen but embodied it.

In 1937, a wealthy American woman, Ruth Everett, showed up at a Buddhist Lodge meeting accompanied by her daughter, Eleanor. Watts was overwhelmed by the mother—who, having spent time in a Japanese monastery, knew more about Zen than he—and was smitten with the daughter. Eleanor had an American vivaciousness and freedom of behaviour unlike anything he had encountered in the few girls he had been with prior. When Ruth returned to America, Eleanor stayed behind.

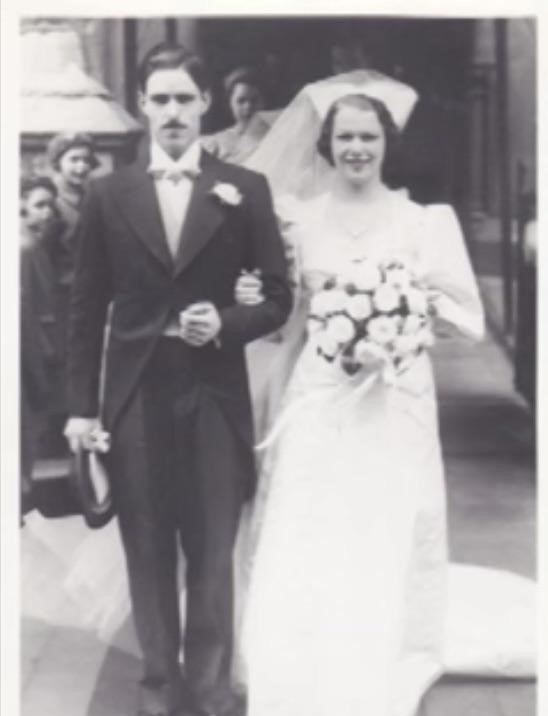

Alan and Eleanor were married in April 1938. Although they both professed to be Buddhists, it was a traditional Anglican ceremony. Watts was 23. Eleanor was 18 and pregnant. The young couple moved to New York where Ruth had arranged an apartment for them next door to hers.

Through Ruth, Watts met the Japanese Zen Master, Sokei-an Sasaki. Watts made an effort to work with Sasaki but discovered—as he would realize throughout his life—that he preferred being the teacher to being the student. After their brief formal relationship ended, Watts continued to observe Sokei-an in order to learn how a Zen master lived his life, something which became easier to do when Sokei-an began his courtship of Ruth after her husband’s death.

Possibly because she was having difficulties as a young mother, possibly because she still lived closer to her own mother and her mother’s influence than she would have liked, Eleanor did not fare as well in New York as her husband. She became increasingly unhappy and depressed. Then one day she stopped in at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, looking for a place to rest during a trying day, and there she had a vision of Jesus so vivid that she could describe in detail everything he was wearing.

This vision came to her around the same time that Watts had become interested in Christian mysticism and was wondering whether—as long as it shed its claim to be the only true religion—Christianity might also be an effective means to achieve that sense of union with God/Dao/Ultimate Reality which in his most recent book, The Meaning of Happiness, Watts had asserted was the purpose of religion and the route to happiness.

Ruth was not surprised when Eleanor and Watts suddenly dropped their purported Buddhism and began attending services at St. Mary the Virgin Episcopalian Church. Not long after this, Watts approached the curate to inquire how he could become a priest. In his autobiography, he struggles to rationalize this decision, explaining that if he were to help Western people understand the “perennial philosophy” underlying all genuine religious traditions, he could best do so within the prevailing tradition of the West.

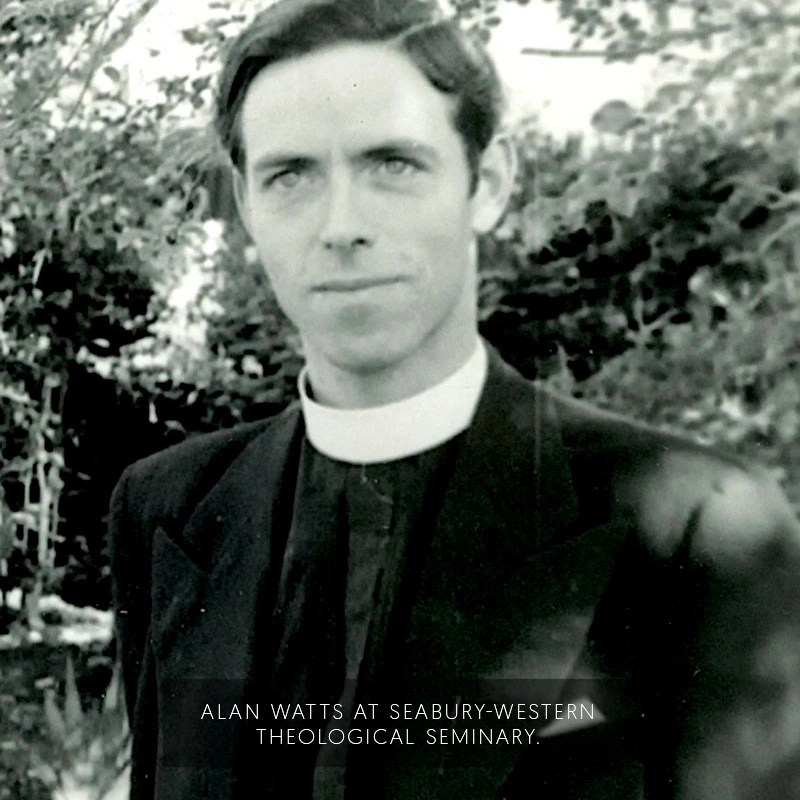

Whatever his motives, Watts and his family moved to Evanston, Illinois, where he entered Seabury-Western Theological Seminary; after which, for six years, the now Reverend Alan Watts served as a chaplain on the campus of Northwestern University. He published another book, Behold the Spirit, in which he compared Christian mysticism with Zen and other Asian traditions. It was well received in church circles.

His clerical career came to an end in 1950, when Eleanor informed his bishop that she and her husband had become estranged in part because of his affairs with women who satisfied desires she was unwilling to fulfill. Nor was Eleanor entirely innocent, having taken a lover ten years younger than she, who—with Watts’ complicity—lived in their house. When Eleanor, already the mother of two daughters, became pregnant with her lover’s child, the situation could no longer be concealed.

Watts resigned his priesthood and affiliation with the Episcopal Church before he could be dismissed, writing a long and self-justifying letter to the bishop in which he asserted that church doctrine had become so out of touch with the realities of contemporary culture that he could no longer, in conscience, continue as its spokesman. It was, at best, a disingenuous argument.

Eleanor procured an annulment, and Watts—behaving almost like a caricature of an adulterous husband—married Dorothy DeWitt, one of his students and his daughters’ sometime babysitter. He retained custody of his children—Eleanor was content with her new son—but no longer had the financial security his former wife’s wealth had provided him. His income from writing was inadequate to support his new family, so he accepted an invitation to move to San Francisco in order to help Frederic Spiegelberg establish the American Academy of Asian Studies. He shed his nominal Christianity and returned to nominal Buddhism without compunction.

Watts loved California and immersed himself in the burgeoning cultural scene although he still came across as a little square. Kerouac portrays him as Arthur Whane in The Dharma Bums. He still had a restrained British manner and dressed formally, and he had what sounded to Americans like a very cultured accent. He came across with authority, and it was natural for him to assume the position of Director of the Academy when Spiegelberg stepped down in order to teach at Stanford.

Watts arranged for a number of interesting guest lecturers to visit the Academy including both Suzuki and his former mother-in-law with whom he appeared to have been able to retain a civil relationship. At any rate, she loved her granddaughters, and they lived with their father.

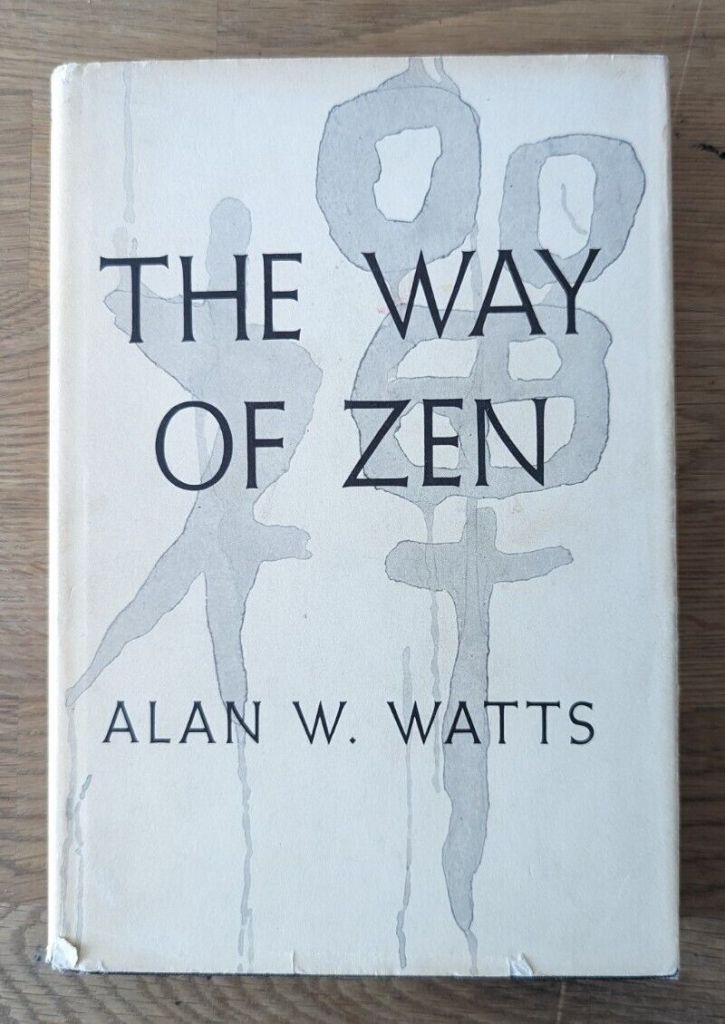

California had long attracted people with an interest in Asian philosophies. Krishnamurti, the Vedandist, Swami Prabhavananda, and other credible spiritual teachers were well established in the state. Watts fit in easily. In addition to his work at the Academy, he became a frequent guest on educational radio and television. Then in 1956, he published the book for which he would become best known, The Way of Zen.

D. T. Suzuki’s books had appealed to a broad but relatively small and well-educated readership. Watts was a much clearer writer and easier to read than Suzuki, and his book introduced Zen to an even wider audience. To some extent it was a matter of timing; the book came out when interest in Zen, in part because of the Beats, was on the rise.

In the book, however, Watts warns that he is not in favour of importing Zen wholesale from Japan: “—for it has become deeply involved with cultural institutions which are quite foreign to us. But there is no doubt there are things which we can learn, or unlearn, from it and apply in our own way.”

He begins his analysis of Zen with a point to which he frequently returns in his work: that what one perceives as one’s Self is an arbitrary social convention. It is not only that one tends to see oneself in light of the way in which others perceive and define one (one’s social role, personality, even physical appearance); one also tends to view the Self as what he described elsewhere as “an ego encapsulated in a bag of skin”—a soul separate from and animating a physical body, both of which (soul and body) are cut off and distinct from the environment about one.

Zen is a “way of liberation” through which the individual can realize the restrictions and limitations of social conventions and come to identify the “self” as part of a larger ecological whole which is all of Being. This is not a matter of rejecting or rebelling against other perspectives. It is rather a matter of seeing through the illusion of separation or dualism. For Watts, this is something which must occur spontaneously; it cannot be achieved by effort.

He presents Zen as a matter of cultivating a particular attitude towards life rather than being a training method which brings about a change in one’s manner of experiencing. Seated meditation – zazen – is just a natural way to sit and be; it had not been intended, he suggests, to become the strained and sustained practice it had evolved into in Japanese monasteries. To support this contention, he quotes a conversation between the Tang dynasty Zen figure Baso and his teacher, Nangaku. Nangaku came upon Baso sitting in zazen and asked, “What is it that you’re trying to accomplish by sitting like this?” Baso replied that he wanted to attain Buddhahood. Nangaku sat down beside him, picked up a piece of broken tile, and began to rub it vigorously. When Baso asked what he was doing, Nangaku said that he was polishing the tile to make it into a mirror.

“But no amount of polishing will turn a tile into a mirror!” Baso complained.

“Neither will any amount of meditation, as you practice it, make you into a Buddha,” Nangaku shot back.

Watts ends the passage at this point. D. T. Suzuki, Philip Kapleau and later Zen practitioners would complain that by doing so he distorted the intent of the story. To present it as a condemnation of zazen, Kapleau wrote, “—is to do violence to the whole spirit of the koan. Nangaku, far from implying that sitting in zazen is as useless as trying to polish a roof tile into a mirror—though it is easy for one who has never practiced Zen to come to such a conclusion—is in fact trying to teach Baso that Buddhahood does not exist outside himself as an object to strive for, since we are all Buddhas from the very first.”

The criticism was just, but, in fairness to Watts, he had specifically denied being a spokesperson for traditional Zen in his book and did not intend it to be an instruction manual. What it did do was present the Zen perspective as an appealing orientation towards life from which Western readers could learn to develop a more healthy relationship with their fellows and their environment than currently found in contemporary North American society.

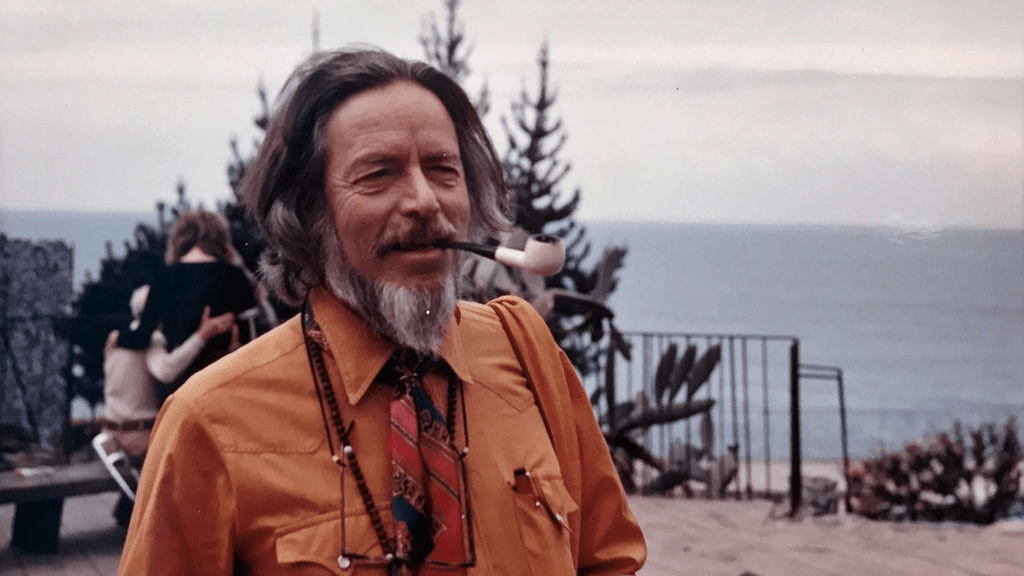

The book became, as Watts put it, a “minor bestseller,” and its publication allowed him to resign his position as Director of the Academy and earn his way as a writer and lecturer. His reputation was on the rise. Tens of thousands of people attended his seminars and read his books. Ironically, his personal life was a mess. He became a heavy drinker and proved to be no more capable of fidelity to Dorothy than he had been to Eleanor.

As his fame grew, so did the number of his detractors. Academics dismissed him as a popularizer, and some members of the emerging American Zen community dismissed him because of his lack of formal training. Shunryu Suzuki, however, when overhearing his students criticize Watts, told them that they should respect what he had accomplished and consider him a great Bodhisattva.

Young people flocked to him and sought to become his disciples; the fact that he did not accept any of them only increased his allure. At the Human Be-In of January 1967, Watts was present with the Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder; Shunryu Suzuki was there as well. In the counterculture, Watts had become mainstream.

The “Summer of Love,” however, was short lived, and, as the original innocence of the first hippies dissipated, a few began serious spiritual quests. Zen centers, located in places as unlikely as Minneapolis, were filling up. The total number of practitioners – many inspired by reading Watts and Suzuki – was not large compared to the general population, but it was large enough to have been unthinkable in 1958 when Kerouac, in The Dharma Bums, had predicted a generation of Zen practitioners across the land.

The Third Step East: 9, 10, 17, 21-39 43, 56, 59, 66-68, 70, 78, 79-80, 82-83 88, 93-107, 112, 113, 121, 127, 134-35, 137, 144, 147, 148, 158, 168, 172, 181, 203, 204, 237-38

The Story of Zen: 5-6, 13-14, 108, 115, 121, 160, 224, 216-25, 231, 233, 234, 237, 244-70, 280-81, 296, 302, 306, 320, 337, 345, 370, 399, 424

17 thoughts on “D. T. Suzuki and Alan Watts”