Adapted from The Story of Zen –

The transference of Buddhism to the west began in the post-Darwinian period at the end of the 19th century when rationalists began to have difficulty accepting the absolutes of the Christian creed but still wanted to believe that there was a spiritual dimension to human life. As a result, even the educated became susceptible to a bizarre range of new beliefs such as in the existence of fairies, spiritualism and communication with the dead, various forms of psychic phenomenon, and even telepathic communications with mystic spiritual masters in the Himalayas. In popular culture, these ideas were often associated with the “Mysterious East,” a region where it was imagined exotic powers were common and life was free of the more restrictive elements of Christian morality.

It was a period of serious academic research as well, and, by the end of the 19th Century, Asian studies had not only acquired a degree of respectability in western universities they also attracted a popular interest unimaginable a few decades earlier. Sir Edwin Arnold’s verse biography of the Buddha – The Light of Asia – became a late Victorian best-seller. The same year Arnold’s book came out, the Oxford scholar, Max Müller, released the first in what would be a fifty-volume series entitled The Sacred Books of the East, a collection of translations he and others had made of Hindu, Buddhist, Confucian, and Daoist texts, as well as works from the Muslim, Jain, and Zoroastrian traditions.

The form of Buddhism with which the West first became familiar was the austere doctrine of the Theravada School as found in Sri Lanka. There a British civil service officer, Thomas Rhys David, translated works which would be included in Müller’s series. Rhys David would go on to found the Pali Text Society, committed to preserving the literary heritage – including the Tripitaka – of what was then known as Ceylon. As documents became more accessible in the West, some thinkers began to wonder if non-theistic Theravadan Buddhism might not be a faith system better suited to bridge the growing rift between science and religion than Christianity.

Knowledge of Mahayana Buddhism came later, when missionaries and philologists began the process of translating Tibetan texts; however, the consensus of scholars like Rhys David was that the Mahayana – with its lurid artwork and suspiciously papist pantheon of Bodhisattvas – was a decadent corruption of the Buddha’s original teachings.

The eventual dominance of Mahayana teaching in the west is largely due to the spread of Zen, but Western knowledge of Zen is historically comparatively recent. The first Zen teacher to set foot in the Americas did not do so until 1893.

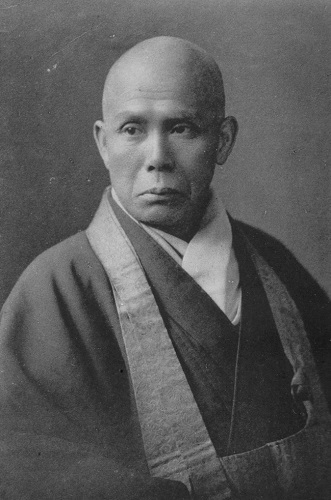

Shaku Soen was born in 1859, just six years after American warships had opened the previously isolated Japan to the west. As a child, he was enrolled in a temple school where – according to his own assessment – he learned to be filial to his parents, helpful to his siblings, loyal to his country, faithful to his compatriots, and respectful of the Three Treasures, Buddha, Dharma [what he taught], and Sangha [the community of his followers]. When Soen was 12, he became a monk, which wasn’t an unusual age for that step.

After working with two prior teachers, he eventually came to study with Imakita Kosen. He mastered the koan system quickly and easily and received inka from Kosen when he was only 25 years old. Normally after receiving transmission, a monk would undertake a pilgrimage to other Zen temples throughout the country to have his understanding tested and deepened, but Kosen encouraged Soen, instead, to enroll in the newly established Keio University in Tokyo.

Soen spent three years there during which he learned about other forms of Buddhism and developed a desire to deepen his understanding of the breadth of Buddhist thought by traveling to Ceylon in order to explore Theravada teachings. Before the opening of Japan to the West, travel restrictions had prevented Japanese from leaving the country and such a journey would have been impossible, but, now that these had been lifted, he was free to undertake the voyage.

It proved to be more challenging than he had anticipated. He admired the lifestyle of the Ceylonese monks and their commitment to the precepts; however, he was never able to communicate with them very well, and he realized that they would be bewildered if he attempted to explain Zen with its emphasis on personal enlightenment. An even greater frustration was the climate. Unused to the heat and humidity of the tropics, he didn’t have the physical endurance to take part in the begging rounds by which the monks traditionally supported themselves. In a letter he wrote to Kosen, he remarked that things in Ceylon were so different that only the barking of the dogs seemed familiar.

Shortly after Shaku returned to Japan, Kosen died, and Soen succeeded him as the abbot of Engakuji.

Like Kosen, Soen was a political conservative and generally accepted the social and economic policies of the Meiji government. He was a product of his era and environment and, as such, took for granted the belief that the Japanese people were the unique descendants of a sacred royal household.

His education, which had trained him to be loyal to his nation and faithful to his compatriots, led him to support the country’s military incursions into China and Russia, and during the Russo-Japanese War [1904-05], he took leave from his duties at Engakuji to serve as a chaplain in the First Army Division. Later he would later argue that the Japanese victory was due, in part, to the strength the nation derived from Buddhist culture and specifically from Zen training which instilled a “Samurai spirit” in the population.

The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair – also known as the Columbian Exposition – was a celebration of the material progress humankind had made in the four hundred years since Columbus’s arrival in the islands of the Caribbean. 27 million people attended the event which was unashamedly an expression of American Exceptionalism. No mention, naturally, was made of the negative impact of the arrival of Europeans on indigenous populations or of other social, environmental, and human costs associated with the march of human progress.

A group of Protestant clergymen saw the fair as an opportunity to hold a World Parliament of Religions in the city at the same time. The Parliament organizers intended to demonstrate that, rather than casting doubt on religion as the evolutionists appeared to have done, modern scholarship – which had now resulted in English translations of most of the world’s scriptures – proved that humankind had been guided by “divine providence through all ages and all lands.” In the same way that the World’s Fair presented America as the pinnacle of material success, the Parliament sought to demonstrate the superiority of Christianity over all other faith traditions. In the closing ceremonies, the Chairman of the Parliament, John Henry Barrows, confidently proclaimed that it had “shown that Christianity is still the great quickener of humanity . . . that there is no teacher to be compared with Christ, and no Saviour excepting Christ . . . I doubt if any Orientals who were present misinterpreted the courtesy with which they were received into a readiness on the part of the American people to accept Oriental faiths in place of their own.” One of those visiting Orientals to whom Barrows referred was Soen.

Soen had only been abbot of Engakuji for a year when he received the invitation to take part in the Parliament. Other, more experienced, abbots advised him to refuse on the grounds that the barbarians of the United States couldn’t possibly understand or appreciate the Buddhadharma. After careful consideration, however, Soen decided to take part. He composed two papers to be presented at the Parliament but, because he had only a rudimentary knowledge of English, asked one of his students, Teitaro Suzuki, to translate them for him.

His principal paper dealt with Buddhist teachings on “cause and effect” and was read to the participants by Barrows. It was received politely but without the enthusiasm which the audience demonstrated for some of the more charismatic Asian presenters. One attendee who was impressed by Soen’s paper, however, was Paul Carus, a publisher and editor intrigued by Asian philosophy. Soen’s paper piqued his interest, and Carus asked the Zen abbot if he would consider remaining in the United States a while longer to participate in a project to prepare translations of Buddhist – in particular, Mahayana – texts for publication in English. Soen demurred, stating that he was not qualified to do so and that his duties at Engakuji prevented him from taking on other responsibilities; he noted, however, that the young student who had translated his paper into English might be up to the task.

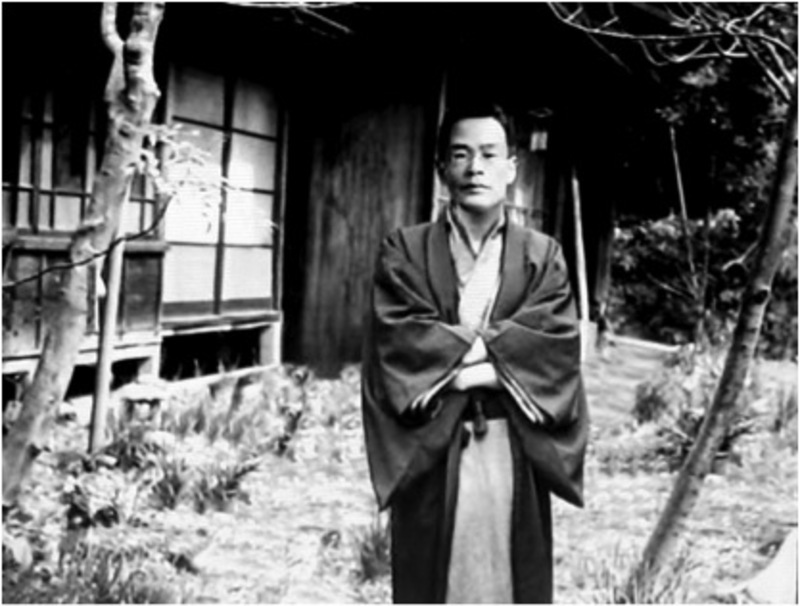

So it was that D. T. Suzuki came to Illinois in 1897, and – with him – Zen would arrive in the West.

Portrait of Shaku Soen by Molly Macnaughton from “Zen Masters of Japan”

Zen Masters of Japan: 295-99

The Story of Zen: 213-23, 229-34, 337

Thanks

LikeLike

Thank you for this valuable history.

LikeLike