Howling Dragon Zen, Vermont –

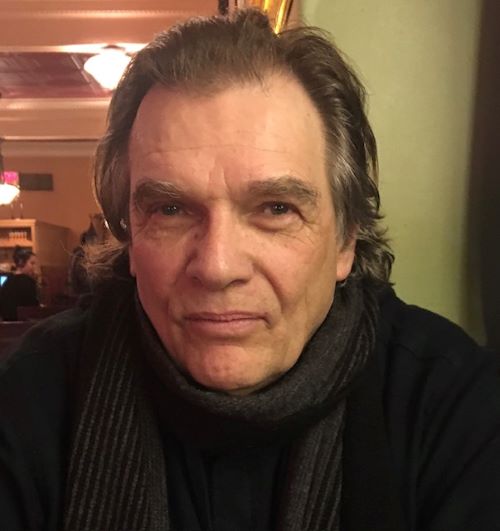

A book on physics first drew Jim Bastien to Zen Practice. He was working at Boys Town – the Catholic orphanage in Nebraska – “when I came across this book called The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that book, but he wrote it back in the 1970s. It’s a treatise on the parallels between Eastern religious views and modern science, particularly quantum physics. And when I read that book, it was like, ‘Okay. Now I have found a way to reconcile my scientific training and a way of thinking with my spiritual sense without having to buy the traditional conventional Christian viewpoint.’”

Jim had been raised in New England in a working-class family plagued by alcoholism and trauma. He mixed with a group of kids who were deemed delinquent and was placed on probation by the time he was 16. “About a year later I got into a fight on a Friday night after drinking and broke this kid’s collarbone. And the Chief of Police told the judge, ‘I want him to go to Westfield State Training School because he’s incorrigible, and he’s got issues, and I’ve had enough.’ Plus the kid who I broke his collar bone, his mother was a big deal in the town. So she made a big stink about it. Anyway, I was already on probation, and so my probation officer basically said to the judge, ‘Hey, he’s a good kid. He’s on the football team. He’s an A student. But he comes from a home where there’s not a lot of supervision at times. There’s no point in putting him in a training school.’ So the judge listened to that, and I got two years’ probation until I was 18, but I was allowed to stay out of the training school.”

He managed to turn his life around and became a product of the times. He was one of the 400,000 people who attended the 1969 Woodstock Music Festival; he experimented with LSD and marijuana, studied Skinnerian philosophy, and got a Master’s Degree in social work, which earned him the job at Boys Town.

“It was a big epiphany to learn that Zen actually had an empirical basis to it. And once I read that book, I said, ‘I’ve gotta find a Zen Center somewhere.’ So I opened the Omaha, Nebraska, phone book, and I flipped to the last page, and, sure enough, Nebraska Zen Center. So I called them up, and I said, ‘How do I do this?’ And the guy who ran it was this physics professor, of all things, at the University of Nebraska in Omaha. His name was Gordon Becker, and he was affiliated with the Minnesota Zen Center under Katagiri Roshi. There were about five of us that would sit in his living room every day, Monday through Saturday, and do zazen, and on Saturday we’d go out to breakfast afterwards. And every once in a while, we’d travel up to Minnesota to the Zen Center there. And they also had a place called Hokyoji which was like a retreat center. That was it. I would get up every morning at 5:00 and drive the thirty minutes across town in Omaha, sit two periods, and then drive back home. Shower, shave, etcetera, and go to work. Yeah, I did that – like – for three years.”

It wasn’t something he talked about with others. “I kept it on the down-low because when I was doing this it was back in 1980. I moved to Nebraska in 1979, and I started sitting in 1980. And in those days, you couldn’t go into a bookstore and find a book on Zen. You might find Alan Watts’ The Way of Zen and one D. T. Suzuki book, but that was it. And Omaha, Nebraska, of course, is right in the heart of the Bible-belt. Very, very heavy Christian culture there. And I’m workin’ at Boys Town, which is like the preeminent Catholic charitable organization for kids, right? So I’m kind of like this closet Zen practitioner. But eventually I started to come out, and it wasn’t as big of an issue as I thought it was.”

“What drew you to the practice?” I ask.

“I think it was my first taste of what I call the mind of not-knowing, that what was going on in my head was not everything, was not the whole thing. And that there was this part of myself that I’d probably lost touch of going way back that was present and welcoming and still and essentially the medium through which experience came through. But it wasn’t just the experience. It was something that was bigger than that, and I was very interested in exploring that, seeing where that would go. And another thing – and I don’t know where this comes from – but I actually love the forms. I love the bowing; I love the chanting; I love the sitting. I just really, really like it. And so I did it from 1980, and in ’85 or ’86 I did jukai with Katagiri.”

I ask what Katagiri Roshi was like, and it turns out that Jim is one of those people who don’t need prompting. Once they start a story, they just run with it.

“Well, here’s the deal with Katagiri. I met him only twice basically. Actually three times. This guy, Gordon Becker, decided to build a zendo onto his house. He moved out of his living room and moved into the kind of addition he built and turned it into a zendo. And Katagiri came down to initiate the zendo, and there was a bunch of ceremonies that went with that. And so I got to meet him for the first time. And it was during that visit that I asked him if he would be willing to accept me as a student. And he knew I had been very conscientiously practising all these years so he said, ‘Yes.’ But he said, ‘You’ll have to come to Minnesota, and you’ll go through a weekend retreat there, and then you’re also going to learn how to sew a rakusu.’ So I went up there and did a two-day retreat and completed that. And then when it was time to go through the ceremony, it was scheduled for the Sunday after the seven-day Rohatsu sesshin, which was the first week-long sesshin that I ever attended. I had a pretty major kensho that was confirmed by Katagiri. And it was interesting too because he gave me the name ‘Daikan,’ which means Great Tolerance. And in the after-party, he came over to me, and his name was Dainin, which means Great Patience. And he took my rakusu, and he took his rakusu, and he went, ‘Look at that.’ And then he gave me a big hug. And the interesting thing about it, the kensho experience I had occurred when I heard a cough that he had made. And when the cough happened it was – this is the term that’s used – ‘body and mind dropping off.’ It was very, very powerful. But it also turned out that that cough signified the fact that he had a rare form of leukemia. And so when I met with him, after he had confirmed the kensho, I said, ‘Well, what should I do now?’ And he said, ‘What do you want to do?’ And I said, ‘Well, I think I would like to ordain as a priest.’ And he said, ‘Tell me about your family.’ And I said, ‘I live in Nebraska. I’ve got three kids, and I work at Boys Town. And I have a wife, etcetera.’ And he said, ‘What I want you to do is for the next two years, I want you to make your work and your family your practice. And if at the end of two years you still want to be a priest, I’ll ordain you.’ I said, ‘Thank you,’ and that was the last time I ever saw him because he ended up deteriorating pretty rapidly. Five or six months later, he passed away.

“About the time that happened, there was an opportunity to start a Boys Town in New England in Rhode Island. So I was tasked to go and lead that project, and I moved my family out of Nebraska to Rhode Island. And there weren’t any Soto Zen sitting groups anywhere nearby, so I started training with the Koreans in Cumberland, Rhode Island, the Kwan Um School of Zen. I did koan study with Seung Sahn, the great Korean master, for about four years. They call it kung-ans, a little different than the Japanese. And my primary teacher was Soeng Hyang, also known as Bobby Rhodes. She’s a hospice nurse, and my sister’s a hospice nurse, and they knew each other. So I did koan study with her, and then after a few years we moved out of Rhode Island and back to Western Massachusetts. And I still went to the Kwan Um School of Zen periodically, but then I decided because I was closer to Zen Mountain Monastery, I thought, ‘I think I’ll take a ride over there and see what that’s like.’ And I went over for a weekend retreat, and Daido Loori was still there. And so I then started training with them as a lay person who didn’t live there. I wasn’t in residence. And I did that for a couple of years. Probably went to three or four retreats of varying lengths. And then one day I’m reading the local newspaper back in Amherst, Massachusetts, and I see an article indicating that Bernie Glassman has just moved into the town five miles from where I live. Because I’d been following Bernie since my days in Nebraska with Katagiri because ZCLA and Minnesota Zen Center and San Francisco Zen Center were like the three where the original teachers came from Japan. So I knew about them. I read their magazine that they would send out. And it turns out, he’s right here in my backyard. Right? So I called up there; I said, ‘What’s goin’ on? How can I get involved?’ They said, ‘Well, Bernie’s not taking any more students.’ But they said, ‘We have these things called Zen Circles, and you can join a Zen Circle.’ It was like a bunch of people got together. It was like one of his upayas, skillful means. You know, Bernie always had these upayas. And so I did that for about a year or so, and then Bernie decided to have this big sesshin. It was the first one he’d done in five years. And he did it at the Kripalu Yoga Retreat Center in Western Mass. And Peter Matthiessen was there; Bernie was there. Enkyo O’Hara was there. Eve Marko was there, and – you know – it was kind of like the Who’s Who in the Zen Peacemakers. And it was kind of a cool retreat because at dokusan you could go to a different teacher on every day. So I saw Peter, and I saw Eve, and I saw Enkyo. And then I got to have a meeting with Bernie. And by then, I’m running a large residential treatment school for youthful sex offenders, essentially emotionally disturbed kids, and juvenile delinquents. So I’m running this 120-bed alternative high school and grammar school. So I meet Bernie, and he says – first thing he says is – ‘What’s your practice?’ I said, ‘I do zazen, etcetera, etcetera.’ He said, ‘Well, what do you do?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m the vice president of residential services running this big treatment centre.’ And he goes, ‘That’s great. How would you like to work for me?’ And I said, ‘You’re kidding.’ And he goes, ‘No. No.’ And I said, ‘A long time ago, I wanted to ordain as a priest and I’ve always kind of held that as something I wanted to do.’ And he said, ‘Well, I’ve disrobed, so I can’t make you a priest. But if you want that – you know – I can figure out a way for that to happen. But,’ he said, ‘I actually don’t think that’s the best path for you. ’Cause of your long history; the things that you’ve done; the education that you have. Your commitment to social service since you were a kid. You know, that whole thing.’ Which is what the Zen Peacemakers are kind of known for. And so I quit my job; I gave up my vice-presidency. My in-laws almost died when that happened. It was all soft money, and I just took a launch. And originally I was President of the Board and then I became the Chief Operating Officer. And essentially I was with Bernie every day for, like, five years. You know, we’d meet in the morning; we’d smoke cigars and plan the day. At lunchtime we’d go down to Subway or a pizza place because he loved eating Subway and pizza.”

“What good is Zen?” I ask him.

“It’s good for nothin’.” We both chuckle, then he says, “I’ll answer the way I always heard Bernie answer. Zen is life. You know, people ask what Zen is, and he says, ‘It’s life. Life.’”

“In that case, what’s the point of all those forms – which you tell me you love – or taking steps like sewing a rakusu or even possibly becoming ordained?”

“Because I think the practice reveals to us what the path out of suffering is. And one of the things that came out of the realization I had is an extremely powerful sense of wanting to help other people. That the actualization of realization is love and compassion. Even against all odds. And it’s not an idea; it’s not a concept. It’s something you know now has to happen and be part of your life. And what is it that you realize? You know, you’re never gonna get an answer to that question because realization is beyond conceptual solutions.”

“Is Zen about realization?”

“Not anymore than eating breakfast.”

“I’m trying to get a sense of what you mean when you use terms like ‘practice,’ a sense of what Zen is.”

“Well, the question is already a problem. If you have to put it in words, it’s always a bit of a problem. You know, in the Soto sect, we’re taught that we’re already enlightened. We don’t have to do anything to become enlightened. And the degree of our enlightenment is oftentimes kind of measured by the extent to which we’re actually in service to other people. So there’s a realization of one’s own enlightenment – okay? – and then there’s the actualization of that realization. And what is that realization? In the simplest words, I would say, it is the oneness and interconnectedness of all life and all things. And once one has . . . I don’t want to say ‘experienced,’ because that turns it into an event. But once one is living out of this oneness and this interconnectedness of life, then everything you’re doing is Zen practice. Everything you’re doing is Zen practice. You know, the Sixth Patriarch, Huineng, a lot of his teaching was about being completely present in the moment without judgment, without fixation and just doing what you’re doing while you’re doing it. Right? Now that sounds simple, but it’s a very, very hard practice to actually do that without getting caught up in our conceptualizing mind which is always going constantly and is in many ways – actually in the most important way – the obstacle to realization. So learning to have a new relationship with your thinking/conceptualizing mind is very important because, as Seung Sahn used to say, the mind is before thinking, before conceptualization. So what are you before conceptualization? That’s the question. And carrying that forward from moment to moment to moment. And this is why I was attracted to Bernie Glassman as a teacher because Bernie had a very, very deep – in my view – understanding. I think more than most people sometimes gave him credit for or realized. Because he was criticized when, like, he started a bakery. Zen students who had worked with him in California when he was with Maezumi Roshi, when he left California and went out his own and started the Zen Center of New York, and eventually the Greystone Bakery and that whole thing that he developed, they left him because he insisted sitting in the zendo doing zazen is equivalent to working in the bakery making donuts if there’s no separation between you and what you’re doing. And a lot of people left him. And they said, ‘Well, that’s not Zen.’ But from my perspective – you know – he had a much deeper understanding of what practice is. Practice and service are not two in my view. Bernie would say, ‘If everyone’s already enlightened, how do I know to what extent I’m enlightened?’ And his answer would be, ‘To the extent that you are in service to others.’”

“Okay,” I say, “so that’s an attitude, a perspective. What I’m wondering is how one acquires the insight whereby I can recognize that the time I spend in the bakery is as valuable as the time I spend in some form of spiritual exercise. What is the process for acquiring that perspective?”

“Well, there’s no formula for this. People used to ask Bernie, ‘How do you determine who your Dharma successor is? What kind of attainment do they have to have demonstrated in order for you to confer Dharma transmission?’ And he had a very interesting answer. His answer was, ‘It doesn’t matter to me how many koans they’ve passed. It doesn’t even matter to me how strong their sitting practice is.’ He said, ‘All that matters to me is the degree to which they are demonstrating in their life the oneness and connectedness of all of life.’”

“Is Zen a belief system?”

He shakes his head. “No, it’s not.”

“So what distinguishes someone who self-identifies as a Zen Buddhist from other forms of Buddhism?”

“It has a lot to do with the practice that speaks to them and that they subscribe to. There are many forms of Buddhism, obviously, and there’s even a number of variants of Zen Buddhism. So one of the metaphors that my teacher used to talk about is it’s like we’re climbing to the top of this mountain – right? – and you got Christians, you’ve got Jews, you’ve got Muslims, you’ve got Zen Buddhists, you got Theravadan Buddhists, you got Nichiren. You’ve got all these different folks that are climbing this mountain and hopefully when they get to the top, they’re all going to have this great epiphany and understand everything and be deeply realized. But when they get to the top of the mountain, they still see it in their own way. But that doesn’t mean that their way is the only way. Even the Dalai Lama once said, ‘It doesn’t matter what religion you practice. What matters is that you practice it.

“You know, Bernie used to ask, ‘What raises the Bodhi-mind, the mind that wants to practice?’ Right? Well the first thing is probably this kind of experience that one has through their life where they keep looking for things that are going to fulfill them in some way, kind of make sense to them, or make them feel more complete. And they achieve those things, but they very quickly realize that they feel empty again. And they kind of go around this wheel over and over and over again. And some people, they just kind of stay on the wheel, and that’s what they do. But there are other people who start to raise a kind of a doubt within themselves, ‘Is the way I’m living all there is? Is this it? Or is there something more here? Because I have a sense that there may be something more here. I don’t know why I feel that way. I don’t know where it comes from, but I’ve got a strong sense that there’s got to be something more than just this process that I go through and I see other people go through.’ And also an understanding and recognition that that process at some level results in suffering. Kind of continuous suffering whether it’s dramatic, moderate, or low level, but there is this feeling of existential angst. And so you might read stuff. These days you can see all kinds of stuff. You can go on YouTube and, like – boom! – it’s all there. But I think what led me to work with a teacher was to see how that teacher was in their moment-to-moment life. I remember when I was at the Nebraska Zen Center, and Katagiri Roshi came down for the weekend. And I remember the first time he came, after morning zazen I went out the front of the house, and Katagiri was standing about five feet in front of me, and there was this big golf course across the street with big, tall pine trees. And it was early in the morning, and there was beautiful sunlight trailing down through the trees, and he was just standing there and staring at this presence. And – you know – being a new Zen student it was like, ‘Ooo, I wanna get a moment with Katagiri.’ Right? So I took two steps towards him, and he took two steps away from me, but never looked back or anything. And it was like a super powerful teaching for me. It was, ‘Whoa!’ You know? This was not about scoring points with the Zen master. Just be with this now,” speaking each word distinctly. “That was powerful for me. And just seeing the grace with which he conducted himself. He was kind of shy. We went out to dinner at this Japanese restaurant, and we had some sushi, and he happened to sit across the table from me. And I’d never had sushi before, so I was a little perplexed; I didn’t know exactly what to do. And he took that . . . I forget the name of it, it’s that green stuff, really potent . . .”

“Wasabi?”

“Yeah! And he mixed it in some soy sauce for me and gave it to me. Never said a word. Just this very elegant, beautiful, graceful presence. And I thought, ‘I wanna get some of that.’”

“So it seems you’re suggesting that Zen is not just some kind of technique – a methodology – to get from one place to another?”

“Yeah, well, I mean sitting zazen is a technique. Koans are techniques. Chanting is a technique. Bowing’s a technique. Working with a teacher – you know, the dialogue back and forth – these are all what Bernie called upayas.”

“And working at the bakery is another upaya?”

“Exactly. If you’re relating to it in a certain way. If you’re not relating to it in a certain way, it’s just – you know – whatever you’re doing, not really a spiritual practice.”

“Tell me about Howling Dragon Zen.”

“What would you like to know about it?”

“Well, first, what it is?”

“Well, right now it’s . . . I have a zendo at my house. I live in a very rural area in Vermont up a dirt road in a little hamlet near a big dairy farm, and I have a big garage. And so I built a zendo over the garage. There’s enough zafus for maybe fourteen people. And so the idea was eventually I would start having a regular practice schedule and begin to work with students. But I’ve held off on that. And the primary reason was that I kind of see Zen practice as my daily activity. So I was working full-time at the VA as a clinical social worker or doing my private practice in the evenings or working on the faculty of the Engaged Mindfulness Institute. I also have board responsibilities on the Orange County Restorative Justice Center. I’m the board treasurer. I see all of those activities as practice activities not as jobs. So I got transmission back in 2011 from Bernie, and I really wanted to spend some time just really practising in the world in everyday situations, and to really work that kind of practice before getting into a formal sitting schedule and students and interviews and that kind of thing. So now that I’m retired, the plan has been to begin that process since I have more time available to start putting together a schedule and making it available to people and making it known that the zendo is here. But I’m also a little bit ambivalent about it because I realize that that’s a big-time commitment. And I look at some of the famous adepts of the past – like Layman Pang and Shantideva and Vilamakirti – they didn’t really have students. That wasn’t their thing. It was about being in the world. I always liked the Ten Ox Herding Pictures, that last frame, ‘Coming Back into the Marketplace,’ and being with people in a way that the flowers come into bloom. That’s kind of what I find is closest to my heart in terms of what practice is, not that I have a bunch of students or have a lot of retreats or that kind of thing.”

“But kind of like Gordon Becker, you built the zendo even though you haven’t taken the step of opening it up to others.”

“I sit there every day. I mean, I’ve been sitting there every day for eight years.”

“What would it take for you to accept students?”

“You know, people contact me from time to time. And I get letters every once in a while from folks in prison. I don’t know yet.”

“How do the folks in prison know about you?”

“Howling Dragon Zen is listed on a kind of list of Zen Centers in Vermont. So you can find that online.”

“And when people ask about the zendo?”

“I say I’m not accepting students currently.”

“So that brings me back to what it would take for you to do so?”

“I don’t know yet. I really don’t know. It’s gonna come from within myself, and it’s a little bit like a koan. I mean, I could do like Ben Franklin, reasons for/reasons against. But it’ll come to me. The answer will appear at some point.”

One hopes that it will. My impression is that Jim would make a powerful teacher.

I recently had the opportunity to share some time with Daikan and practice together. I really appreciate his understanding of the Dharma and the way he brings an informed practice to living his life. He’s a bodhisattva for sure.

LikeLike