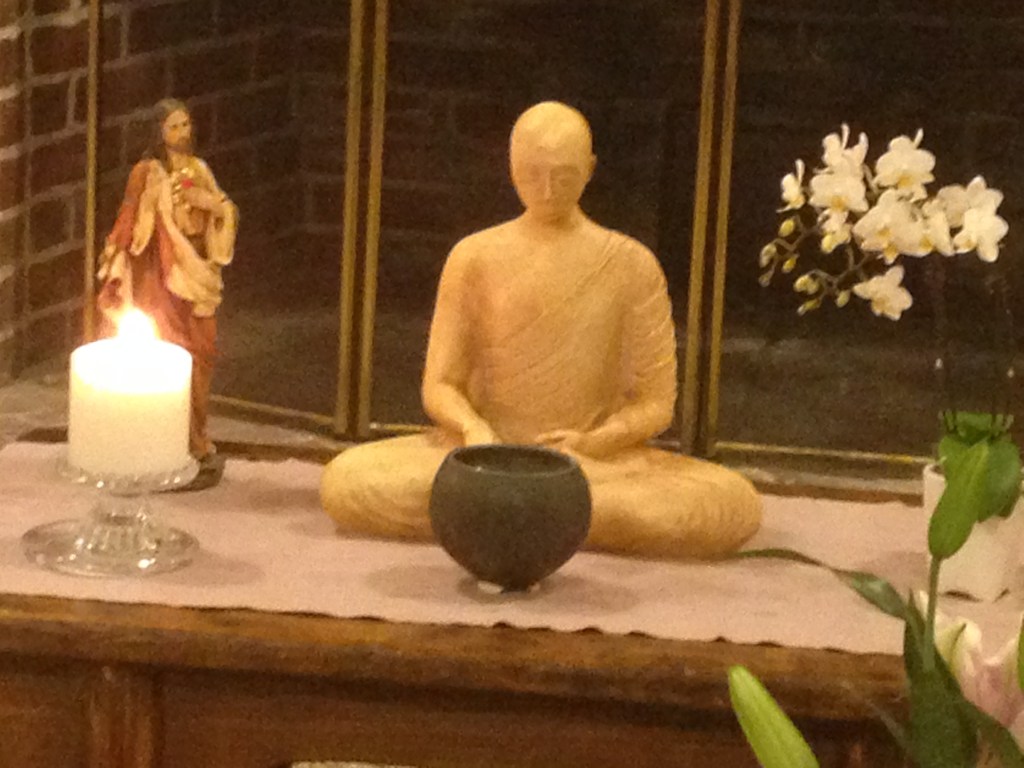

Day Star Zendo – Wrentham, Massachusetts

Cynthia Taberner helped to arrange my 2016 visit to Father Kevin Hunt’s Day Star Zendo in Wrentham, Massachusetts. The day I spent there became the basis of one the chapters of Catholicism and Zen. Kevin – who is a Trappist monk as well as a Zen master – has now retired from teaching. Roshi Cindy, as she is called, is his successor; however, she is preparing to pass that responsibility onto others because she has pancreatic cancer.

“I’m on chemo, but it can stop working at any point. I was misdiagnosed with vasculitis, so the cancer is now in the arteries, and there is no way to survive it. I could be around for a couple of years or in a few months I could take a downturn. So I’m trying to make the new teachers as independent as possible and have the sangha go on because it’s a wonderful group of people. It’s a very eclectic group of people. We have Catholic nuns. We have an Episcopalian priest. We have people who are Jewish; we have people who are agnostic.”

I ask Cindy if she still self-identifies as Catholic.

“I’m going say I’m Christian. I was raised Catholic. I’ve never been a theologian. I’ve been more into the mystical since I was a kid. So I will have a Catholic mass, but I will ask that some chants be done as well.”

It takes me a moment to realize she is talking about her funeral. Her condition is that severe.

She was raised, she tells me, “one town down from Father Kevin. He was at St. Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, and I was raised in Leicester. And so I used to go up to the abbey and just sit in their quiet church and contemplate for years before I knew he was there. So it was really interesting that he was there and I was able to meet him later.”

She was drawn to the quiet of the chapel as a refuge because her childhood homelife was “very rocky. My father was an alcoholic. It was in the family. He was very violent. It went from male to male to male to male. So a very rough childhood. So I think I was always a seeker because of that.”

“What were you seeking?”

“I was trying to make sense of it all. Even during my childhood, when they talked about a loving God, I wondered, ‘How could a loving God ever allow this?’ I was always wondering did I do something wrong? Did God hate me? What did I do wrong to deserve this? So you try to seek those answers.”

Eventually she lost her faith.

“There was a time when I did not believe in God at all. I think it was in my late teens, early twenties. I also had a genetic illness. It’s called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; it’s a connective tissue disorder, a rare kind of genetic illness. So I was getting sicker and sicker and sicker. And between my childhood and then this illness, I thought, ‘There can’t be a God.’ But in 1982, I had a near-death experience, and, when I had that experience, I knew there was a God.

“I had an ectopic pregnancy that ruptured, and I bled out. I can only tell you what I sensed when it was happening to me. And it was such a sense of peace, such a sense of love, like I was wrapped in it; I was part of it. And I didn’t want to come back. I had a year-and-a-half-year-old child, and I remember thinking at the time, ‘She’ll be fine. I want to stay here.’ And when I did come back, I was so depressed that I didn’t stay where I was. And here I had this little baby. Right? So, then it changed me, and it was a gift. It was a gift that I had had that experience.”

She was introduced to meditation when her physician recommended that, in order to prepare to undergo a surgical procedure, she attend the Mindfulness-Based Stress-Reduction Clinic recently established by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts. One of the teachers was Elana Rosenbaum. “She was in the Vipassana tradition, and I worked with her every single week and sat and loved it. But then I wanted more, and I heard about this Zen group in the area, and I thought, ‘I’m going to try that.’”

She liked the Zen group, and she thought the teachers were fabulous. “So I was attending both Elana’s group, and I was also doing Zen. But they had a guest teacher there once. And he basically told me I couldn’t do Zen and Christianity at the same time. I asked, ‘Why? I’ve been doing it all this time. Why is that a problem?’ And I walked away from the temple. But then by chance I came upon an inter-religious dialogue on the computer. I don’t know how I found it, but all of a sudden I see Father Kevin Hunt at Spencer Abbey is on it. It’s really bizarre how that happened. So I sent an email and said, ‘Is it possible to speak with Father Hunt?’ And about a week later I got a response, and he said, ‘Yes, you can come up.’ So I went up. And I said, ‘Well, this was said to me, and I’m curious. Can I do both?’ And he said, ‘Well, what’s the problem?’”

The guest teacher who had told her Zen was incompatible with Christianity probably did so because he viewed them as belief systems. For Kevin, Cindy, and others who remain affiliated with non-Buddhist traditions, Zen is almost precisely the opposite of a belief system, it is a technique – an upaya – not a creed.

“That’s exactly it,” Cindy says. “We use it as a technique. But, you know, in all of Zen you get rid of everything. You even get rid of Catholicism or Christianity. You get rid of all the thoughts. You go down to nothing. To no thing, or ‘nothing.’ You get rid of all concepts. You do. But in my experience, in my Zen, we do have that as part of us because we were raised with that consciousness. Right? So I think of it as Christ-Consciousness. Zen is Buddha-Nature which I think of as the same as Christ-Consciousness. As I said, I’m not a theologian; so I don’t look for all the things that can contradict that. I think of it all as being the same.

“I’ll tell you of an experience I had while I was with that first Zen Center. We got up to do kinhin, and for a split second – just a split second – Christ was right beside me, and then he was inside me. So I was thinking nothing – right? – and then this happened. I explained it to the teachers, but they didn’t want to talk about that. And I talked about it to Kevin when I met him. I said, ‘This happened to me. And I don’t quite understand it.’ And I didn’t at the time. And he said, ‘Oh, for Heaven’s sake, that just means that Christ is one and the same as you. That’s it. He’s just telling you you’re one and the same.’ And it was like, ‘Oh! That’s right! It’s simply that.’ So it’s easy for me to put the two together. It’s easy for me to think of Zen and Christ-Consciousness and Buddha-Nature as one thing, and that Christ came to us to show us the way, just like Buddha came to us to show us the way. Christ had it in his consciousness already to show us, ‘This is the journey, folks. I want to show you a way.’ I could be wrong. I’m sure a lot of theologians would say, ‘No! No! That’s not true!’ But for me, it was easy to put the two together, and especially having Kevin as a teacher.”

“What is Zen?” I ask her.

“What is Zen? Zen is living in the moment. Living in this moment only. It’s a gift. For me, it’s living as One. You know that passage in the sutras, ‘Not two but one’? So I think of it as, we’re part of the mystery. We’re not separated from the mystery. And by living in the moment, we can see that we’re not separated from the mystery. We’re living that moment fully. Absolutely fully. And that allows us to live with an open heart and an open mind. If we don’t live in the moment, we’re living a dream life. Living a dream life. Living in the moment gives us the opportunity to really know who we are. Of course, you have to get through layers of junk first. I had to get through layers of childhood. Layers of things that happened to me – layers of stuff that were wounding to look at – to get to that wisdom where we’re united to that mystery. So we’re united in this mystery, and I don’t care what you call it. You can call it Christ-consciousness, you can call it universal energy, you can call it Buddha-Nature. I don’t care what you call it. We all share in this. But we have to live in the moment to realize it. That’s Zen to me. It’s not just sitting on the cushion. It’s getting up off that cushion and living each moment fully, fully aware. And saying yes to life, even though you don’t want to. So when this diagnosis came to me, I had to say ‘yes’ even though I didn’t want to. And so it’s not just saying yes to the happy, joyful things. It’s saying yes to everything and being fully present for it all.”

There is a line from the Third Patriarch’s Xinxin Ming which is referenced several times in the koans of The Blue Cliff Record: “The Great Way is without difficulty, it only dislikes picking and choosing.”

“Father Kevin and I have talked about this,” Cindy tells me. “In life we don’t have any control. There’s really no control. We think we’re in control until we know we’re not. And that’s part of that ‘picking and choosing.’ You don’t get to pick and choose what happens in this life. But what we do get to choose is being awake to it. And so we can shut our eyes and close our selves off; close our hearts off – our ‘heart-minds’ I want to say – or we can choose to stay open to whatever’s in this moment. I think that’s what that means. It’s staying open to whatever is there. And whatever is there is not always to our liking,” she adds with a chuckle.

“How does meditation work?” I ask. “If Zen is this receptivity to what’s happening right now, what does plunking oneself down on a cushion have to do with that?”

“And we just breathe. Right? So I call it breathing, letting go of everything. Talk about picking and choosing.” She shakes her head. “No. Just let it all go. All thoughts go away; everything goes away. And then I call it ‘being breathed.’ I always feel like I’m being breathed. Not that I am doing the breathing; I’m being breathed. And eventually even that goes away. And then you get this unity. And I can’t explain it to you. I can’t put it into words. I cannot put it into words. But there you feel whole. That’s where I feel most whole.”

“There are people who find it very difficult,” I point out. “I remember David Rynick in Worcester once telling me that when he started meditating he could only last about two minutes. He’d dutifully set his kitchen timer for two minutes and would just about be jumping out of his skin before it rang.”

Cindy laughs. “I could see that with David. So, to me, meditation is not for everyone. I suggest, sometimes, walking meditation for people. My sister loves nature. Nature, to my sister, is like sitting in zazen. When she goes out into nature, she gets the same sense. So meditation is notfor everyone. It’s not an easy practice. It’s a tough practice. Sometimes you don’t feel like sitting. When I first started sitting, I didn’t like it either. But nothing else was working for me so I needed to continue to sit, and I eventually was very, very, very grateful for it. But it took a lot of practice. And then you get these dry spells where all you’re doing is sitting there and maybe your mind is going crazy and maybe everything is happening, and you feel like, ‘God! I’ve been sitting for years, and this is still happening?’ It takes a lot of discipline. And perhaps some people don’t want it enough, or perhaps some people just can’t do it. And that’s okay. They’ll find their own way. You know, I very rarely go to mass – maybe I shouldn’t admit that – but I very rarely go to mass. But when I do, there’s a sense of comfort there. And I think it’s because in my childhood it’s what gave me some sanity, thinking there was something or someone watching over me. So maybe that’s what I need when I go to church.” She smiles and adds, “And there’s a Catholic priest that I’m friends with who’s into Dorothy Day, and he’s got this whole Dorothy Day center in Worcester, so I don’t go to your normal Catholic church.”

“You found a left-wing radical commie-pinko church,” I say with a laugh.

“You know what? I did. I did, and I love it.”

“What does a Zen teacher teach?”

She chuckles and then says, “Nothing” with a laugh.” (One day I’m going to learn not to ask that question any longer.)

“So it would be a waste of time for me to come to your group, huh?”

“We point the way. So I didn’t really want to be a teacher, by the way. I thought my illness would get in the way of teaching, and when Father Kevin invited me to be a teacher, I said, ‘I’m not sure I want to be a teacher.’ But he brought me to meet Bernie Glassman Roshi, and Bernie said, ‘Your life is your teaching, Cindy. And you will be a teacher.’ Your life is your teaching. And he was correct. So I think if we are really truthful, it’s our life – it’s the way we live our life – that can be helpful to students. As for the practice of Zen, I can teach you to sit. And then when questions come up, maybe I can help you decipher them. Maybe I can help you decipher. Maybe I can help point the way a little bit. But can I do it for everybody? No. Not at all.”

“What do the students who have formally taken you on as their teacher expect from you?”

“You know, not much. Because I tell them not to expect much. So I’m there for them as experiences happen or as their practice matures and I’m able to help them along, again, just pointing a finger and helping them along, but that’s it. They don’t look to me for answers. In fact, I think they look to me for more questions. When they ask me questions, I usually have a question back for them.”

“Well, that tells me what you do, but it doesn’t tell me what they’re looking for.”

“I think what they’re looking for is what I found. Which is a peace and a joyfulness even within life’s craziness. Elana told me she began meditating after she met a man who was a meditator and felt, ‘I want what he’s got.’ I think they see that. One person in particular is getting older, and he said, ‘I’m having trouble with death. And here I am, I end up with a teacher who has an illness that’s going to kill her.’ Right? So, he’s had questions, and he’s watched me, and he’s said, ‘I don’t know how you have the grace to do what you’re doing.’ I said, ‘I don’t either.’ So I think each student wants something different from me. Sometimes I may disappoint a student because I’m not really giving them the answers. I’m really just pointing the way for them. I can tell them when they’re off-center. When they seem to be going off, I can tell them, ‘No. You need to be here. You need to be grounded. This is where Zen is; it’s grounded.’ So I can’t be everything to all people, but I think the very serious students that I have, they’re looking to me for help on their journey with groundedness, staying on track. And perhaps . . . I don’t know. We get energy from each other. Even online, even on Zoom. We sit each morning, and then we sit every other Saturday, and I believe we get energy from each other. And maybe that’s part of it too. Just that. Sitting with each other. Sangha’s so important. For me it’s always been. I gain strength from the sangha. It gives us strength.

As our conversation wraps up, I ask if there was anything she would have liked to talk about that we hadn’t touched on.

“I don’t think so. I do want to thank Kevin. I couldn’t have had a better teacher. He really helped me. I don’t know what I would have done without him. So I want to say that. I think he’s been one of my biggest graces throughout my life, and so I’m so grateful for him. And I think I want to thank my sangha. They’ve hung together for all these years, and I think we’ve strengthened and helped one another on our journey. So what I feel is gratitude. I don’t know where I am in this journey or when my life will end. I don’t know when the chemo will stop helping. But I’m so grateful for my life. I’m so grateful for this journey. I’m so grateful I found Zen. I don’t know that I could do this illness without my practice. I don’t know that I could do this illness without my sangha. I’m . . . I’m just grateful.”

A little more than a year after I interviewed her for this profile, Roshi Cindy died on October 25, 2024.

Catholicism and Zen: 15-16, 168-80

Grateful to have Cindy’s words, wisdom, deep connections, and journey captured. I wonder if there is audio of this interview to share.

LikeLike