When, in 2013, I began the set of interviews which were the basis of Cypress Trees in the Garden, I was still pretty naïve about the state of Zen in North America. I had assumed that the sites I had arranged to visit would be more or less similar to the center where I had practiced with Albert Low in Montreal. How wrong that assumption was became obvious at my first stop which was the San Francisco Zen Center.

A year after San Francisco I traveled to Boston. It was the first time my wife and I had been to the city. Our hotel by the airport overlooked the harbor, and, as I worked on my notes, a sailboat race took place below us. The view was impressive. The short city tour we’d done had been informative and fun. The driving . . . Well, the only way I could make sense of it was that driving had been deliberately made as unpleasant as possible in order to encourage the use of public transport.

I was in Boston in order to interview Josh Bartok who, at the time, was the resident teacher of the Greater Boston Zen Center actually located in Cambridge. Google-maps made the run from my hotel to the center look simpler than it was. The GPS instructions (“Left turn, then left turn ahead”) came more rapidly than I could follow and usually when I was two lanes from where I needed to be. So I arrived a little flustered.

The first thing I noted about Josh was that – at 43 – he was younger than the other teachers I had interviewed until then. “I’m youngish for a Zen teacher,” he admitted.

After completing his undergraduate work, instead of going onto graduate studies in cognitive science as he’d intended, he spent a year and a half at Zen Mountain Monastery. Then he fell away from formal practice for a while, even had a stint as a professional Tarot reader. Finally, through his work as an editor with a Buddhist publishing house, he met James Ford and began his first post-monastery intensive work with a teacher. By my calculation, it was less than twelve years later that he was authorized as a teacher himself. Maybe not a record, but it did lead me to think he probably had a natural affinity for the Dharma.

One of the assumptions I had at the time was that Zen students were supposed to identify a personal teacher and stick with them. That was how I understood my relationship with Albert. Once you find a teacher and present the box of incense, they’re the guy with whom you do dokusan – private interviews – forsaking all others. Josh, however, was one of a group of four teachers who actively encouraged students to attend dokusan with more than one person.

“If you only go to dokusan with one teacher,” he explained, “you can come to equate the Dharma with that particular teacher’s presentation of it. But when you go to four teachers, it is like Venn Diagrams; there is a very real and essential area where all four circles overlap. But there are also large parts of those circles that do not overlap.” He has a talent for coming up with effective analogies.

The importance of being able to distinguish the Dharma from personal character should have been self-evident, but it hadn’t been to me until Josh pointed it out. That affected every other interview conducted from that point on, and my focus became less the areas that overlapped than those which didn’t.

Being a Zen teacher – as Josh recently told me – “is hard work. And the mantle of it is heavy.” I would add, it is also a role on which Zen students often project unrealistic expectations.

Ten years later, in 2023, Josh is no longer a teacher. He had returned his priestly robes and transmission documents to James two years earlier.

He had been in a relationship with a student and came forward to report this to the other teachers and the ombudsperson of his community; he resigned as teacher and Spiritual Director the following month. Until I approached him for an interview in 2022, he had made no public statement other than the March 2021 apology ceremony led by the then-teachers of his former spiritual community. When I asked what he would like to share publicly about his current situation, he directed me to what he’d said in that apology:

I acknowledge that I inappropriately crossed boundaries in relationship that were my own sacred responsibility to hold and that I created circumstances of secrecy and deceit. Caught myself by the energies of suffering, I amplified suffering in others rather than diminishing it, and I disrupted this community. I betrayed all of your trust, and I betrayed the vows and values I myself hold most dear. I am so deeply, deeply sorry for these things. I make this apology to you all and in front of you all as embodiments of the Three Treasures. I assure you I take to heart the implications of this transgression, and I vow to continue my deepening work in understanding and addressing the causes and conditions that led to my failures and my harm-causing so I can prevent them in the future.

As he speaks about his situation, there are frequent reflective pauses – one exceeding 90 seconds – and several false starts. This is not easy for him.

“It was humbling for me to see so clearly how badly I could screw up and how lost I could become even after all of my practice, and even from places of love for the Dharma, love for the community, love for people I was in relationship with.

“Amid this, at a time of inner and outer upheaval, I did things that hurt some of the people I cared most about. Having done these things and acknowledged my responsibility for having done them, I have done and continue to do a lot of psychological, spiritual, interpersonal, and self-reflective work to understand this and be able to cause the ‘less harm’ that I have always aspired to cause with my life. I’ve reflected and continue to reflect deeply on myself as a teacher and leader, on my weaknesses and blind spots, and on what and how I was and wasn’t teaching and the impacts of my shortcomings on others.

“And so I set all of this stuff down to remove myself from that. I don’t want to be in a position where my own difficulties, my own failings, my own falling short of my values and my aspirations and the things I know to be true and good, where those things have such ramified, amplified impact on so many other people.

“And, still: I’m doing my best to learn from and grow from the incredibly painful realities of this karma and am still trying to walk the Dharma path as well as my karma allows. Beyond trying to not do harm, I am also trying, in such ways as are available to me, to actualize some good.”

It was appropriate for Josh to resign. Zen Communities have become strict about matters of personal conduct, and that’s as it should be. On the other hand, as I continue to conduct these interviews, I not infrequently encounter people who lament the loss of a skillful and compassionate teacher, one to whom I remain grateful for helping me discern an approach to these interviews that has held me in good stead.

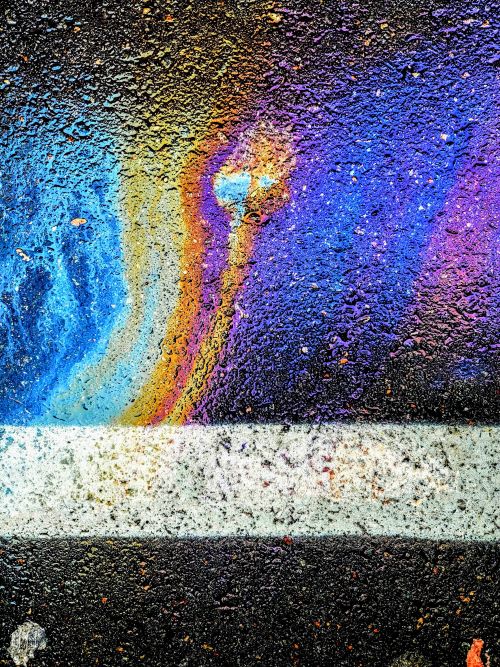

[Photos by Josh Bartok]

Cypress Trees in the Garden: 223-233

Josh is awesome. His book with Ezra Bayda (Being Zen) was the medicine I needed at a major turning point in my life. He’s done great work at Wisdom Publications. I’m sorry to hear of his slip up, but undoubtedly it will only ripen his compassion and embodiment of the dharma. Peace Brother _/|\_

LikeLike

I’ll echo Anonymous above. I’m fortunate enough to have spent time learning from Josh. Hearing he’d been suspended for misconduct was surprising, but the details presented here seem much more like the guy I know. Not perfect, but still striving. Also, ethics aside, a hell of a photographer.

LikeLike

The fact that this teacher refers to what happened with a student as a “relationship” (and that you do) shows that neither of you understand the nature of sexual misconduct. There are reasons why therapists cannot cross lines with clients, clergy with practitioners, priests with parishioners (or whatever that would be in a Buddhist context). These are not “relationships” of equal measure. A “relationship” would be one of integrity between a teacher / student, clergy / practitioner, etc. If sexual misconduct occurs, that is not a relationship. It’s the most essential rule *of* right-relationship in these contexts. Unfortunately it seems like Buddhism is suffering from what Christian religions in this country have for a long time, too, a rampant misuse of power. It’s really sad when someone is harmed spiritually, because it’s such a vulnerable place that should be one of refuge and safety for life’s harms, not betrayal and harm itself. The quotes in this article are all about the teacher, and even the “remorse” seems to be about his own self. Victims of spiritual harm can become so invisible, which is part of the many harmful effects of spiritual abuse. Until this teacher and interviewers like yourself can find a more accurate descriptor than “relationship” for this behavior, it’s really not contributing to make the world or even Buddhist world a more compassionate and wise place.

LikeLike