Manzanita Village Retreat Center, San Diego County, CA

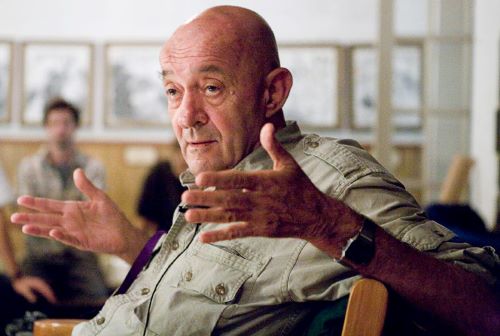

Caitriona Reed is one of the co-founders of the Manzanita Village Retreat Center in San Diego, California. I note the remnants of a British accent, and she admits that she’s from the UK. “I came here on holiday forty years ago and forgot to go back. I had dual nationality, so that made it easier.” She was 30 when she moved to the US, but her formative years had been in England. She is trans so attended a male boarding school which, she assures me, was as brutal as the portrayals in novels and television programs suggest.

“Every morning began with chapel, hymns, and prayers. Tears. It was Dickensian in the bullying and the randomness. However academically, I was blessed. They did actually teach you how to think for yourself in the academic sense. By implication, we were being raised to administer an empire that no longer existed. But what else are you going to do?”

She encountered Buddhism through books. “There was not an overt religiosity in my family, and, as a child, I invented my own. I found myself innately devout at the age of about eleven or twelve. And then I took like a fish to water reading first Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and then Christmas Humphries, Alan Watts. Buddhism became a context for my rebellion, which continues to this day I should say.”

I ask what the rebellion was directed towards.

“The sense of ‘get me out of this!’ Get me out of this where people – where we – are not collectively thinking through the consequences of our activities, where we are not living in the sacred.”

She is one of those persons who can take a question and run with it, anticipating later questions I don’t need to ask.

“So, I’ll dive straight in and say that as a Buddhist teacher and practitioner for many years, I no longer identify particularly with Buddhism,” she continues without pause. “The experience of illumination is beyond cultural context. I first heard this from Gary Snyder many years ago, that you could contrive to say that the Buddha was attempting to revive a universal paleolithic cultural embodiment, and that the early Buddhist sangha was an attempt to do that. He included across classes; he included untouchables; he included women. He looked to create a bridge between the monastic sangha and lay people. The early sangha’s form of governance was based on a council form which we know from reports among the Huron Indians in Canada, we know – if not universal – it was a common way that people practiced self-governance. They would sit down and listen to each other. So I relate very strongly to Indigenous cultures; I do Indigenous practices of prayer, of quest. I work with Plant Medicine, meaning psychotropic medicines both in South America and here. Several years ago. I had this illumination, ‘Oh, my God! Now I understand what I’ve been teaching all these years!’ Because there was something about embodiment, the kind of embodiment that comes from prayer rather than the way meditation is taught or received in our Western culture where we commodify, where we look to see to what advantage it will provide. We don’t surrender in humility; we meditate in order to improve ourselves. That’s our context. However well zazen or any form of meditation is taught, our cultural orientation is such that we turn it into a self-improvement strategy. ‘How can I do this better to get better? How can I improve myself.’ And I’ve discovered that there are other ways to be in the world that are more akin to – for want of a better word because this is the word of the civilized mind – an animistic view. Everything’s alive. Everything is interacting. Everything is conscious. Everything matters. There’s a sense that we are simply a piece in the matrix of Creation. And, of course, Zen practice leads us to that eventually. If we’re lucky. But there is so much to get through – in my experience – before we arrive at that simplicity.”

I ask how old she was when she read Watts and Humphreys.

“I was fifteen or sixteen when I read Alan Watts’ Way of Zen, and it was very exciting. It was really exciting to me.”

“What made it exciting?”

“Two things. The cultural context, the allure of East Asia. The culture of Tang Dynasty China, the introduction of Zen to Japan, and then the actuality of the experience of the real, the experience of the immediate. At that time, I was experimenting with psychedelics. LSD was still legal at that point.”

I, too, am old enough to have taken acid before it became illegal to do so.

“I was too young to be a Beat or a beatnik,” she says. “But I was old enough to aspire to be a hippie and lived that way. And my first meditation was in some hippie place in London where someone was teaching a very yogic, Hindu-Indian-influenced form of devotion meditation. Soon after that I spent time in Samye Ling, the Tibetan monastery that Chogyam Trungpa started in Scotland, but he’d left by then to go the US. This was ’69 or ’70.”

“What was Samye Ling like?”

“I found it confusing. It was very Tibetan. I didn’t understand Tibetan. And I went to see Akong Rinpoche and said, ‘So, I understand that you meditate by following your breath.’ He said, ‘That’s fine. Yeah. Go on. Do that.’ Easier said than done for a 19-year-old with a head filled with all kinds of things. And it wasn’t until I went to Sri Lanka – I was 28 – and sat for extended retreats in a couple of Theravadan monasteries that things improved.”

“How did you come to be in Sri Lanka?”

“I was a photographer. I needed to leave a marriage. I needed to be in India. India had captured my imagination. And when I was at the Ramana Ashram in South India, I said I was going to Sri Lanka, and someone said, ‘Go to Kanduboda monastery. You’ll find a teacher there by the name Sivali. Sit with him.’ And I did. I spent some weeks there, and I went to a country monastery where there was an American monk-teacher and spent a couple of months there. And the course was set. I was really excited about Theravadan-style practice.”

“Again,” I ask, “what was the allure?”

“Oh, the experience of being present. Just the fruits of the meditation itself. And I was extensively reading contemporary Theravadan scholarship. There was a writer – I don’t recall his name – teaching at that time in Honolulu. He was Sri Lankan in origin, but he was very broad, and he wrote about Mahayana and Theravada and their relationships. Later on – when I became a student of Thich Nhat Hanh – I appreciated Thay for the breadth of his embrace of Theravada, Mahayana, and Pure Land. Well, Pure Land is Mahayana. But it wasn’t a singular adherence to a singular school of thinking or practice. It was much broader than that.”

The “holiday” for which she’d left Britain at the age of 30 was, in fact, a three-month retreat at Barre, Massachusetts, where the Insight Meditation Center is located. After that, she visited a monk she’d met in Sri Lanka who was then teaching in Los Angeles. “And he asked me to teach with him. I was completely unprepared to teach. So I suffered for ten years from imposter syndrome while teaching retreats. Initially a very formal Theravadan-style retreat of sitting and walking meditation. And I continued to teach with him uninterruptedly until 1981 when I fired him basically. I said, ‘I can’t do this with you anymore.’ He was a brilliant teacher for me because he was so iconoclastic. His name was Akasa Levi. And he was teacher both to myself and my partner with whom I’ve been teaching for almost forty years now.”

Her partner is Michele Benzamin-Miki, a visual and performance artist as well as a martial arts instructor. The program they developed, Five Changes, evolved from their early work together.

“That work was very much rooted in the Theravadan tradition in form. Very quickly, we started speaking from a place of social responsibility, of politically and socially engaged Buddhism. My partner is a person of mixed race, so there was some fuel there, and there was fuel anyway in the sensibilities of both of us. It seemed absurd to think of Buddhist practice as entirely transcendent, transcendental, something that could be done aside from the reality of the times. And in the 1980s, you remember, we were at war overtly in many parts of Central America; Reagan was threatening us all with mutually assured destruction. And so that led us, very quickly, to affiliate with Joanna Macy, with the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, with Engaged Buddhism. So, naturally, we met Thich Nhat Hanh who apparently coined the term ‘Engaged Buddhism’ and also said there was no such thing as Engaged Buddhism because Buddhism, by default, is engaged. Though you wouldn’t know it sometimes from the way the Buddha Dharma is practiced both in Asia and in the West. So we were creating a hybrid already, and then when we met Thich Nhat Hanh it became hybridized even more. And we maintained forms. We taught silent retreats but more and more relaxed. I remember early on Thich Nhat Hanh said if you’re not really enjoying your meditation practice, something is off there. Something is wrong.”

Caitriona’s Wikipedia entry identifies her as “an American Zen Teacher in the lineage of Thich Nhat Hanh.” I am not clear how formal that authorization from him is, but, at least, it was adequate to earn her membership in the American Zen Teachers Association.

I ask how she met him.

“I’d heard about him. I’d read some of the things he had written in English when I was in Sri Lanka. I knew he was in France. I had made some inquiries about how to find him, but he was very much on retreat in a hermitage until the early ’80s. This was the late ’70s when I was in Sri Lanka. When he came to the US in ’87, I went with him to an ecumenical retreat in Santa Barbara. It was very small, unlike at the end of his life when he had retreats with thousands of people. This was forty people at a Catholic retreat center. And as we introduced ourselves in a circle, I said to him, ‘I’m sort of feeling I’m ready to graduate from Buddhism.’ And he really liked that, and he riffed on that in one of the Dharma talks he gave, this idea of graduating from something we name, from something that we identify with, from something that has a structure that we enclose ourselves within. And we became friends, I have to say. We tell people we knew Thich Nhat Hanh before he was famous. We went to France a lot, and our teaching changed completely. We didn’t abandon Vipassana, but we didn’t adopt Vietnamese Zen either. We certainly adopted some of the teaching styles. And his tradition is very much in the Rinzai tradition. So there was certainly some dialogue, less formal than what you think of as koan practice. I mean the koan curriculum comes from a specific time and place in Tang Dynasty China, and it’s become this thing that we now call the koan curriculum. With Thay it was very much like walking into the kitchen and saying, ‘What are you doing?’ And you’d have to realize that was a koan; he wasn’t going to give that away. And he talked about it. He said, ‘You could say I’m cutting carrots, or you could say I’m bringing Buddhism back to China.’ It could go either way. He played with people, in a very loving way, I have to say.”

I ask about the Manzanita Village Retreat Center.

“Manzanita Village is a place we’ve been for thirty years. We’ve lived on this land. It’s very remote. We have one neighbor over the ridge behind me, and other than that our nearest neighbors are more than a mile – in most cases five miles – away. We live in a little canyon. Behind us are 180,000 acres of National Forest land, and in front of us is 2000 acres of pasture. So we have a sense of being buffered while at the same time being within two and a half hours of Los Angeles. We hold various retreats that we teach, and these days we integrate multiple modalities. We work with family constellations . . . Are you familiar with Family Constellation work?”

I am not.

“No? It’s a very interesting hybrid because it has roots in psychotherapy, but it’s the opposite of psychotherapy. It looks like psychodrama, but it doesn’t play out like psychodrama because nobody knows what they’re doing. It comes from Bert Hellinger[1] in Austria. He was a Jesuit; he went to South Africa where he worked with the Zulu for many years. So it has elements of Freud, and it has elements of indigenous practices. It’s very blind. A person, a client, would want to resolve in something in their life, and the work has the assumption that because of generational loyalties that we have to parents and ancestors we enact our relationships in certain ways. The anger, the fear, the whatever it might be that we carry is often not our own but enacted out of a loyalty. And sometimes a client just witnessing the choreography of people who don’t know what they’re representing can release generations of conditioning. Every time we facilitate, I’m blown away by the magic of it. And we will ask the participants, ‘How do you feel about so-and-so? Do you want to move closer or further away?’ It plays out. And the client will say, ‘How come they’re talking just like my mother? What did you say to them?’ I didn’t say anything. I don’t know your mother. How could I tell them to talk like your mother? People do a constellation for their relationship with their brother they haven’t spoken to in years. And after we finish the session which could last half an hour, it could last ten minutes, then they receive a text from their brother, apologizing for his behavior, and thanking her for all that she’s done for the family. Within minutes – within a minute – of finishing this work, without any communication, from across the country or across the planet. There is something in it. We could call it the morphogenic field – you know, we could reify it be calling it something – but it is simply the way that we are interconnected in life. The way the phone rings, and we know who that is even though we haven’t spoken to them for a year oftentimes. It’s extraordinary. And I’ll say, because this is what influenced my life and my practice more than anything, since the Enlightenment we’ve been creating a mechanized world in response to the world that is much more than us.” She’s not talking about the Buddha’s enlightenment but rather the 18th Century European Age of Reason; it took me a moment to realize that. “At first, we tried to describe it, and now we try to explain it, and then finally we try to take it to pieces and then, after that, destroy it. And in the process, ignore the magic that is everywhere. I once saw a scrub jay on the ground next to a rabbit for an hour. What were they doing? They were certainly facing each other, making gestures, communicating, at ease. Neither one of them was cornered. They were voluntarily spending time with one another. We don’t have any mechanism for that in the way that we think of the nonhuman world. We don’t even give it time so that we can spend an hour observing this whatever it was. Call it conversation. And I feel that the practice of the Dharma was given to us as a way to rectify this. But so often because of – for want of a better word – our egos, we miss the point, and try to get ‘enlightened.’ As if that would help the world! Like, why try to get enlightened? Just be here now. Someone said that before me,” she adds with a laugh. “Just be here now! And it will unfold magically. And so the last time I endeavored to go off on my own before this place – more than thirty years ago – to a Zen Center which is in the lineage of Maezumi, up in the mountains, quite near us, I went to do a sitting retreat on my own. And I made the mistake of bringing with me Katagiri’s first book. Which in the first chapter – which I read on the first day – said, ‘If you try to attain something in your practice, you’ve already kicked the bucket over. You’ve already set yourself up for something that is known. So why even bother?’ I paraphrase entirely. But it led me to think there was nothing I could do, nothing I could do here in contriving a practice, contriving to sit eighteen hours a day over a five-day period, that could in anyway improve my life. Just relax. So I did. I spent five days reading a little, sitting a little, walking a little. And it was the last time I ever tried to do a solo – one-on-one – just myself on retreat. So my path was very much set out for me and then later, through Thich Nhat Hanh, to, ‘Just relax.’”

“So Manzanita is a place, a location,” I say. “What is ‘Five Changes’?”

“Five Changes is the name of the work we do.”

“Is it a program?”

“It’s an umbrella term for the various things we do. In addition to constellation work, we teach hypnosis, we teach neural linguistics. I’m thinking of teaching a course online called ‘Meditation, Prayer, and Trance.’ ‘Cause in the minds of most people – I think – those are three very separate things, and they’re really different ways of defining aspects of the same thing, which is how to be present, how to be humble, how to be real, how to bear witness. Everything we do in the Five Changes is really a form of prayer, a form of meditation, a form of facilitation. Every time we do anything, we begin by asking permission of the ancestors of this land that we do this work. That’s a very Buddhist thing to do, actually; I don’t know how many people do that when they lead retreats, to actually invoke the blood ancestry, the spiritual ancestry, the land, the ancestry of the land where we stand. And then from there it evolves as an offering, as a way of coming closer to the spirit that infuses all things, the spirit that infuses all traditions whether it’s sophisticated – like Buddhism in all its manifestations – or very simple like the way some of the indigenous people we’ve known in South America or North America just simply offer tobacco, offer a prayer without any complicated conceptual structure surrounding that. Just simply a way of being. So Five Changes. It’s a brand, and the tag line for the brand is: ‘For the world we long for.’ And no one has ever asked me what that is, because we all long for a world which is sustainable.”

“And when you say Five Changes, are there specifically five elements you’re referring to?”

“Well, there are different things I say. It could be the five elements of Chinese medicine. Often I’ll say something like, ‘Well – you know – there’s probably one thing in your life you want to change right now. Let’s do that. But know that there are at least four more that we can address later.’”

“Southern California,” I point out, “there’s a lot of options for people looking for spiritual direction. What draws someone to Manzanita rather than to, say, Maezumi’s place in Los Angeles?”

“Night and day. Because we begin in a way by saying – we don’t say it overtly – that we don’t know what we’re doing. We don’t know what we’re going to do next. And it’s one of the reasons we never built an empire.”

“That might be what they’ll discover when then come to Manzanita Village, but what is it that draws them to you in the first place?”

“Ah! I see. Well, it’s something they’ve read about us. It’s often by word of mouth. Or it’s something from our website that attracts them or what we’ve written. It’s something about the fact we have affiliations to multiple disciplines, to multiple perspectives. We don’t identify as any particular lineage, any particular modality, any particular tradition. And over the years we’ve been continually changing it up. For many years we were working with deep ecology, with global grief work. We used to teach with Joanna Macy, and then it morphed again. And now we do constellation work. We’ve done theatre work in the context of retreats. Theatre work that’s theatre not in the sense of role-playing, theatre in the way of embodying presence with sound and movement. Why? Because it was an interesting experiment. Did people benefit? Probably. Virtually everyone’s forgotten it. Only we remember it.”

“And when someone makes their way to Manzanita, what are they looking for?”

There is a seven second pause before she responds.

“Well, they’ll do it in a couple of different contexts. They might come to a workshop or a retreat in which they come for whatever we’ve written up that that retreat’s going to be about. Or they come because they haven’t seen us for a few years and it’s time to reconnect.”

“I’m thinking about someone who comes for the first time. What draws them to you?”

“They’re coming because they want something that’s a little outside the box. They may already and may continue to be doing some kind of formal practice in Zen or Vipassana, but they understand innately that what’s available, what’s possible for them, is more than – you know, I don’t want to be disparaging – but more than the formula, more than the set modality or the set curriculum.”

“So people who have been involved in some kind of spiritual program but now feel some sort of dissatisfaction with it?”

“Not a dissatisfaction but a sense that there’s more.”

“Isn’t that a form of dissatisfaction?”

“Or it’s a hunger, it’s curiosity, it’s an energy. Often they’re artists because I’m a writer and Michelle’s a painter. Often it’s that that draws them because there is something perhaps dry in yoga, in meditation.”

“What is it that you hope for the people who come to you?”

“I hope . . . I hope that they will burst into their life, embodied, fearless, and embrace the creativity that is given to them in whatever form that takes. That they will be free from anxiety and fear.”

“Which implies they come to you with anxiety and fear.”

“Yes. Of course. Of course. And if they didn’t, that would . . . You know, in 1990 when James Hillman came back from Italy as a union analyst and a scholar, he gave up practicing psychotherapy saying, ‘I want nothing to do with helping people feel anything but depressed and anxious. That’s what we should all be feeling.’ So it’s relative. How to navigate the turmoil and horror of living in a world whose future is entirely uncertain, and especially when I talk to people in their 30s, and more and more I find myself with younger people. And it’s much harder for them than for us to deal with whatever thoughts that they’re having about what the world will look like in ten or twenty years. So it’s to help people with anxiety and uncertainty, but with the understanding that it isn’t possible to do that because of the world that we live in. And, of course, I don’t want Buddhism to be used as a way of sedation. ‘It’s alright; it’s One; we’ll all get enlightened; we’ll be reborn.’ That’s nonsense. That’s denial, resignation. It’s awful to abuse the teachings in that way.”

“What is the value of maintaining the Dharma?”

“Oh, lovely! Because it’s so beautiful. Because it’s the embodiment of this multi-stranded 2500-year-old tradition of literature and art and thought and embodiment, of truth-telling, of amazing courage, amazing just beauty and courage. You know, all that we have in these times over the last several thousand years, from Pythagoras, Socrates, the Buddha, Nagarjuna, the richness of the Christian tradition, the richness of the Dionysian tradition, the value is to celebrate this multifarious flowering of human possibility. But I don’t see the Dharma as necessarily outside of the context of the human flowering. It does have particularities that I’m forever grateful for, and it’s that balancing. You know, in Buddhism it’s that balancing of wisdom and compassion. It’s the balancing of inner and outer, of self and other, the recognition of how we construct our reality. And that marks it as slightly different from other so-called religions. And so for that I think it’s of value to preserve the Dharma. That it’s both particular and it’s part of this beautiful flowering of the last 5000 years of our experience together on the planet.”