Monterey Bay Zen Center, California –

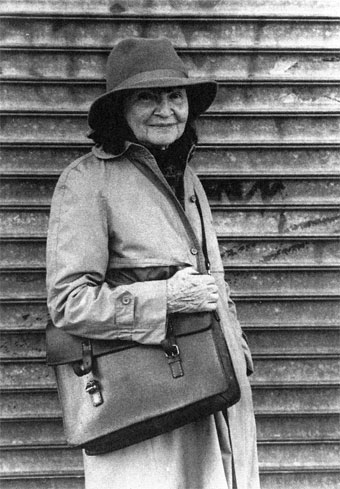

Patricia Wolff is a lay member of the teaching council at the Monterey Bay Zen Center. The other three members are ordained. She is also a chiropractor, a homeopathic physician, and a psychotherapist.

“I feel like I’m the eccentric aunt in the sangha. As a teacher, it is important to me to share how my Zen practice is not just on the cushion but is how I live my life, how I use this practice to bear the unbearable or to deal with difficult emotions. I’m kind of the same in my Dharma talks as I am with my patients, as I am with my children, as I am with my friends.”

She tells me she grew up in a family which was culturally Jewish. “We were the Jews that came out of the woodwork for the High Holidays.”

“Did it mean anything to you as a child?” I ask.

“What it meant for me as a child was I couldn’t understand the liturgy. I couldn’t understand why if God was all-knowing we had to keep telling him how great he was. It made no sense to me. I just didn’t get it. I was talking to my brother about it, and he said, ‘It’s like, “Hey, God! You’re lookin’ good; you been workin’ out?”’ So, yeah, Judaism was really cultural. It wasn’t until I was in college that I realized not everyone thought the Jews were the Chosen People; that only Jews thought that Jews were the Chosen People.”

“You hadn’t encountered any form of negativity growing up?”

“Well, yeah, but I always thought it was because everyone was jealous because we were the Chosen People.” We both laugh. “Maybe a little bit,” she continues more seriously, “but not much.”

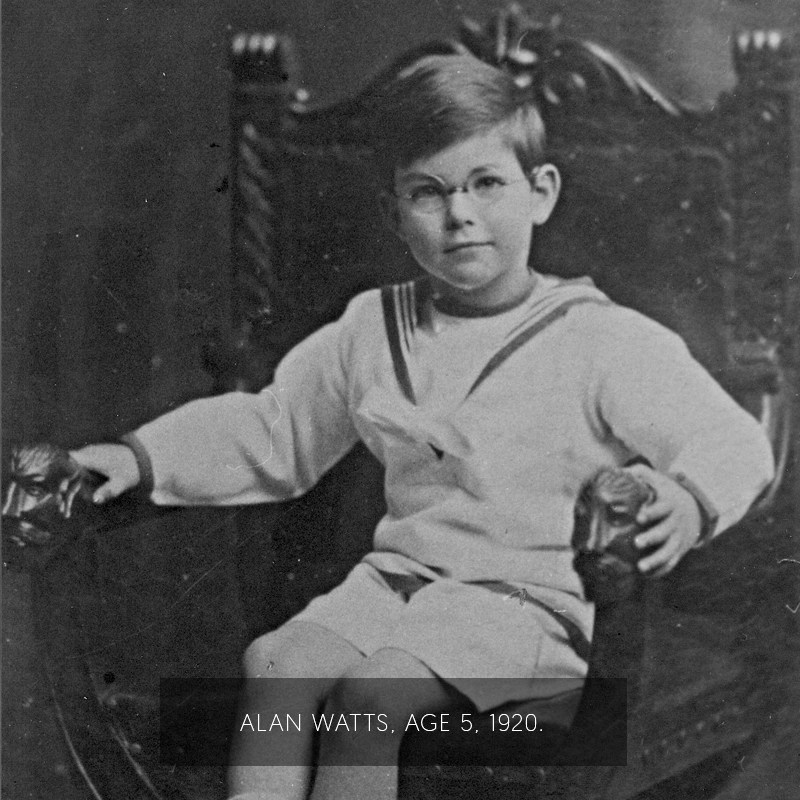

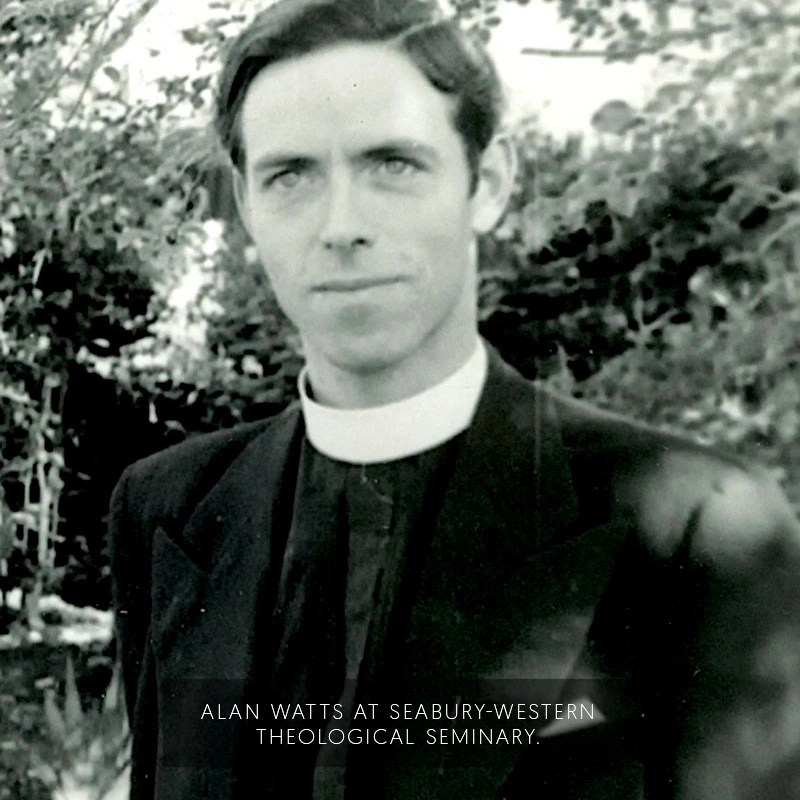

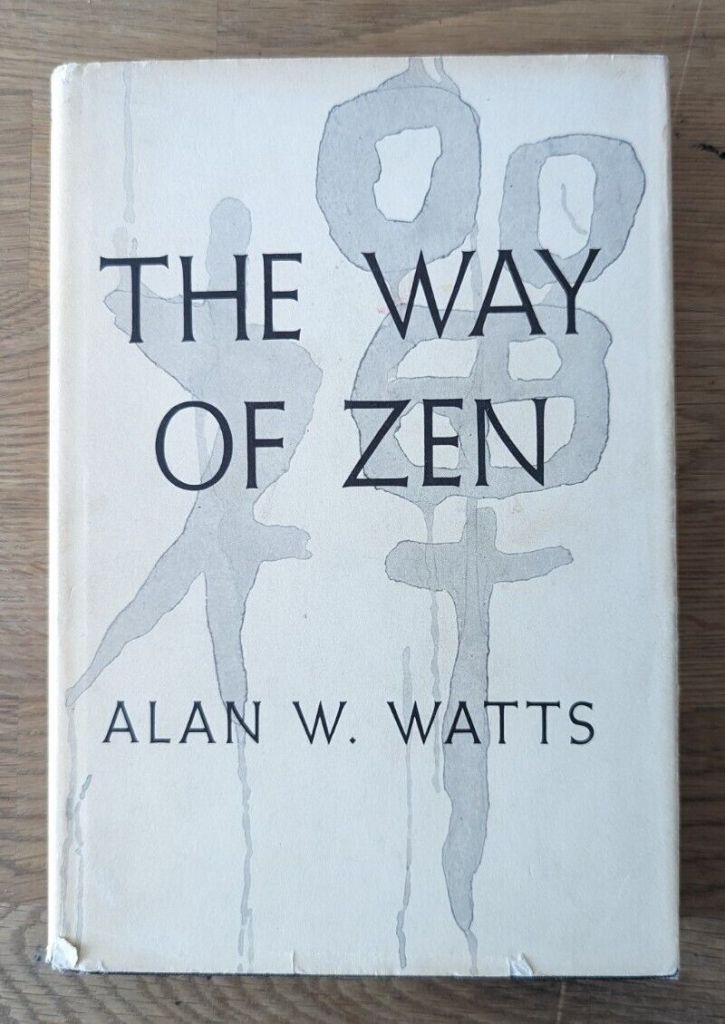

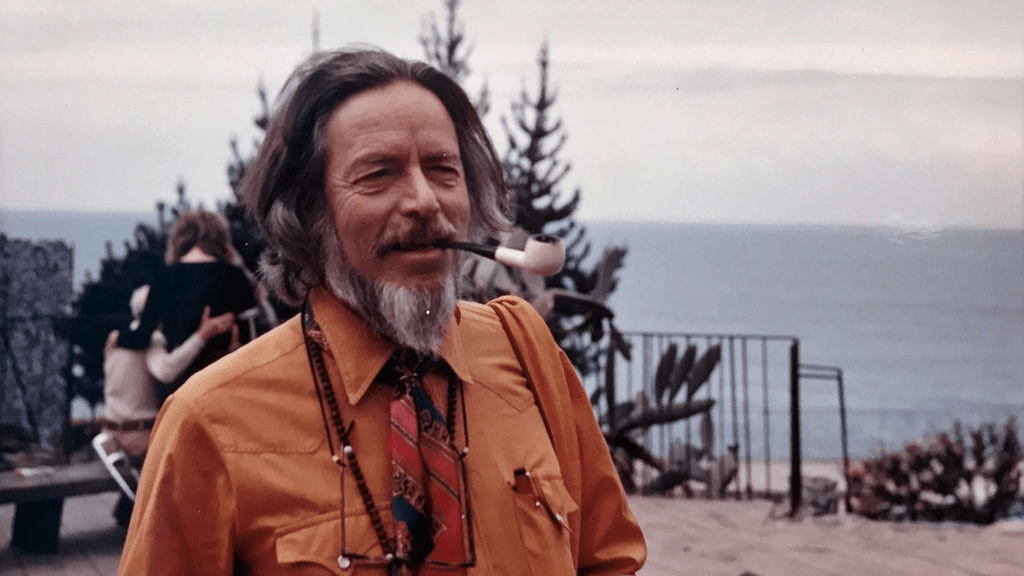

She first encountered Buddhism in her senior year at Cornell College. “I needed an art class to graduate, and the only thing that fit into my schedule was Asian Art History. And I read Alan Watts, and we studied the Southern Sung landscapes which were these giant scrolls of mountains and gorges with the human beings as these insignificant little ants. And reading Alan Watts changed me.”

“In what way?”

“The whole concept that humans are just one part of the fabric of the universe, and God not being something out there that we worshipped but this collective . . . not deity, but just that God was in each one of us. It wasn’t something ‘out there’; it was part of us. In addition to not understanding the Jewish liturgy, another of the things that boggled my imagination was the notion of infinity. I would try to grasp infinity, and it would just bring me to tears because I couldn’t get it. I couldn’t understand it. And I think there was something about Alan Watts that helped me shift my relationship with the great unknown. As a child I thought that God and Mother Nature were married. That was kind of my creation myth. God and Mother Nature were married.”

It would be a while before she actually began a meditation practice.

She earned a degree in psychotherapy which helped her realize there was still some personal work she needed to do. A woman she worked with as a client told her about TM and a Tibetan practice she was engaged in. That planted some seeds. Then she went on what she calls an odyssey. “I went through Mexico down to Guatemala and Belize. I was on a sailboat for a month with people that I met on the coast of Belize. Got hepatitis and came back to California, because I had an old boyfriend that was there who had moved back to California when we broke up. And I ended up staying in California to become a chiropractor because I wanted to do mind/body medicine. And it wasn’t until I was in practice four years later that I had a patient who said, ‘You have to meet my gynecologist. You’d love each other.’ And she was from Zen Center of Los Angeles. And she had a sitting group for women. I never had anything to do with Zen Center of Los Angeles, but that was my first sitting practice.”

The woman, Renee Potik, was a lay teacher. “She was loving and accepting. And I became aware of my internal self-judgment. She kind of showed me a different way of being with my humanness. And then she moved away.”

Patricia and her partner had a son, and when the child was a year old, they realized they wanted to leave LA. That led to another odyssey which brought them, eventually, to Carmel Valley. And there Patricia met a friend who frequented the San Francisco Zen Center’s wilderness retreat at Tassajara.

“She talked about Tassajara all the time. So once we settled there, I went to Tassajara for the first time. At the dining room, sat next to Katherine Thanas, who I didn’t know, and I said, ‘Oh, I just moved to the area. I’m looking for a sitting group.’ And she said, ‘Well, I just started a sitting group.’ So that’s how I ended up with Soto Zen. I don’t think I would have chosen Soto Zen if I hadn’t sat next to Katherine Thanas at Tassajara. I loved her. I always had an ambivalent relationship with the form, the patriarchy, the chanting in foreign language.”

“So what did you like about it?”

“The notion of facing myself and my life squarely. Really the Four Noble Truths. Also facing my restlessness as a meditator. How judgmental I was as a meditator trying to do it ‘right’.”

She describes her time sitting on the cushion as “torture,” so I’m still unclear what the appeal was.

She considers her reply before answering, speaking slowly and with care. “Because I felt that in the suffering I encountered tremendous self-knowledge and self-compassion. A few years into my practice, I discovered non-violent communication and studied that with my dear, dear friend Jean Morrison from Santa Cruz. Non-violent communication. And those two practices . . . I just felt like it was important in my life. It was the only meditation group that I knew of. Tuesday nights I got to leave my children and go to the Zen Center. No matter what happened, I’m off-duty, even if I didn’t go. Even if I just went into my bedroom, and they’d come and I’d go, ‘Uhn-uhn. This is my Tuesday night. Go find Dad.’ I loved the community; I loved my sangha brothers and sisters. I loved Katherine with all her human rough edges. She was very sincere, earnest, and honest. When she messed up, she was the first to say, ‘I don’t know how to deal with this.’ I found a sense of belonging I think; I found a community. I was new to the area; didn’t know too many people. And there was something that just rang so true.” She adds, however, “I think had I found maybe Insight/Vipassana, that might have been a better fit for me as a therapist and as a healthcare practitioner.”

But she stayed with the practice and eventually even undertook the Shugaku Priest Ordination Training Program – SPOT – offered by Steve Stücky at Tassajara. “I did the three-year teaching-training program which was wonderful. A deep dive both into the emotional world and the Buddhist world. But I think there were only two of us who didn’t become priest ordained. Everyone else did.”

“If only two of you didn’t ordain after that program, it was a choice you made.”

“Oh, I chose. It was a choice.”

“Why?”

“I don’t see Zen as religion. For me it really is a philosophy, a way of life, an invitation to see the world and ourselves the way we are with unconditional friendliness. Finding practices and cultivating skills of compassion, curiosity, and courage. I think in our very lay, house-holder community, priesthood sometimes separates in a hierarchical way.”

She studied other traditions, including the Yoga Sutras and Patanjali. “Much of what I study is not just Zen, and most of what I teach is informed by other traditions which resonate with Zen. It’s an important part of my life because I’m cultivating peace both internally and with all my relations. You know, Steve Stücky had his internal family systems and that is what he taught us a lot in our SPOT training, blending psychotherapy and Buddhist principles. The language that he used and the context of the Buddhist practices has become very important to me, peace-making with all our internal parts and each other. Sp I use non-violent communication, meditation practices, heart-opening practices. And I do it all with the Monterey Bay Zen Center and the people I love.”

I ask if the Monterey center is affiliated with SFZC.

“Not officially. But I’m near Tassajara. So we’re back and forth.”

After Katherine Thanas, who founded the center, died without leaving a successor, a teaching council was formed which included Patricia. The fact that Patricia chose not to ordain was challenging to some, including Katherine, but – Patricia tells me – Katherine became less rigid about things at the end of her life.

“So, I have a green rakusu,” she tells. We both chuckle.

“You know, all these different centers just make this stuff up,” I suggest.

“When my son and daughter came to my lay transmission ceremony, we were in the little gathering area after the ceremony, and he said, ‘Mom, what does that mean? Is it like karate?’ And I said, ‘Well, it kinda is.’ I said, ‘Yeah. It is kind of. Different colours.’ And Katherine overheard me, and she got furious. ‘There is no hierarchy in Zen!’ At first I thought she was joking, but she wasn’t. And I’m thinking, ‘Of course there’s hierarchy!’”

She admits to feeling triggered by “the whole priest thing because the Suzuki Roshi lineage is very priest oriented, and I get upset that I am not allowed to do certain things, that I can’t transmit my own students because I don’t have the appropriate type of transmission. I can’t carry out certain roles because I don’t have the rank. I have the authority but not the rank.”

“But you’ve stayed with the community.”

And that, she says, raises an important question. “Why have I stayed with Monterey Bay Zen Center for thirty-three years?” She pauses a moment. “I don’t know. I love the sangha. Monterey is not a big area. There’s not a lot of other sanghas that meet. But I don’t go every week anymore. I do lead a guided meditation on Zoom Mondays, Wednesday, Thursdays at 12:00. That’s free. That’s an offering to the community that I started in the beginning of COVID. So I’ve been teaching unofficially for years. Because parents of my son’s friends knew that I was a meditator, and they wanted to learn. So I would gather moms together just to teach them how to meditate. I brought it to the schools. The elementary schools and the middle schools and the high schools.”

“And if one of those parents of those school kids asked you, ‘What is meditation? What does it do?’”

Again she reflects a moment before answering. “Meditation offers us the opportunity to know ourselves deeply, to not believe everything we think, to witness the thoughts and emotions as they come and go, to be mindful, to access the great spaces of infinite potential, awareness of awareness itself. When I was leading meditation in the middle schools, the group that came to me for some bizarre reason was a group of six boys. It was lunchtime; they would tumble into the space, and they’d be pushing each other and farting and this and that. I said, ‘I don’t care if you push. I don’t care if you fart. I just want you to know you’re pushing when you’re pushing; I want you to know you’re farting when you’re farting.’ They would meditate for three minutes, maybe five minutes.”

“What instruction did you give them? What did you have them do in those three or so minutes?”

“Well, they just breathe, allowing thoughts to come and go without going on the rollercoaster of preferences and attachments. I usually have people start their practice counting their breaths, noticing sensations and sound. Opening to it all. Feel the air moving in; feel the air moving out. Feel the belly rising, the belly falling. Watch the thoughts as they arrive.”

“And what do people get out of doing that?”

“For me it really comes back down to deeply knowing myself and waking out of our trance. You know the quote, ‘In the beginning mountains are mountains, and rivers are rivers. And then mountains aren’t mountains, and rivers aren’t rivers.’ And then at the end of our cycle, mountains are mountains, rivers rivers, but in a different, more inclusive way. So it’s a process of deeply knowing ourselves, of opening to the entirety of our experience, and finding a place to settle besides our thoughts. I think that’s why guided meditation became really important to me because I didn’t know where else to go besides my thoughts.”

“And what is it that the members of the Monterey Bay Zen Center expect from you?”

“Honesty. Inspiration, perhaps, in how to work with difficult parts of their lives in skillful ways. And I think the invitation for unconditional friendliness with themselves.”

“What is it that brought them there in the first place? What did they come to the Center looking for?”

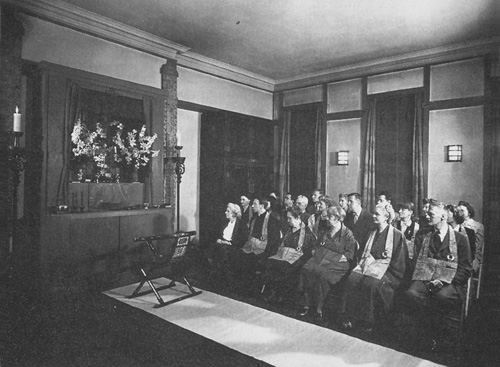

“Many come for a sense of community. A lot of people say that they don’t meditate on their own by themselves, but, coming to a group, they meditate. And I think the sangha is really important, being in community with people sharing the Bodhisattva vow. Some were looking for relief from their suffering, trying to find a way to bear the unbearable, to be with really difficult situations. Some people – especially the Catholics in our group – love the ritual and the ceremony and the incense and chanting in a foreign language, and the robes. You know, that really feels and smells like home. Some are looking for comfort. I think we’re all looking for comfort.”

“One thing you didn’t list, you didn’t say they came looking for awakening or enlightenment. That doesn’t seem to be the driving force it once was, the desire to find a practice that has the potential of altering the way one sees, understands, and relates to life.”

“I think that’s what I mean by unconditional friendliness, being with what arises, facing the entirety of our experience with wisdom and an open heart, embracing all parts of ourselves.”

“You said ‘unconditional friendliness to oneself’ earlier.”

“To yourself. I think that ripples out to the world, seeing no one as ‘other.’ That naturally flows. The more we can bring that, share that light of tender awareness on ourselves, the more we see our interbeing or – you know – our intrabeing, the sense that there is no other. And I do think that people come for enlightenment. It wasn’t what my search was. I think for me it was more because it made sense and offered relief from suffering. It was finally something that made sense of the world to me.”

“And how does Zen help relieve suffering?”

“I think wanting the world to be any different than it is is the definition of suffering, and Zen – or Buddhism – offers the invitation to really be with the world as it is beyond the world of right and wrong, good and bad, to recognize the comparative mind, to not be attached to our preferences , and to just see our constant internal chatter as an annoying radio station in another room. So for me, enlightenment is moments, moments of liberation. I’ve never known anyone that’s landed and stayed there. I don’t really know anybody that I would consider enlightened. I know people who are really wise and have deep understanding and have many moments of that peace. But everyone I know is pretty human as well.”

“So you’ve described an array of services you offer; you’ve talked about guided meditations, chiropracy, psychotherapy, non-violent communication. Where does Zen fit?”

There is another of her careful reflective pauses as she considers her response. “It’s not so much Zen as it’s Buddhism. The practice of meditation, of deeply knowing ourselves, of awakening out of our trance. I remember once talking to Bernie Glassman at my first Lay Zen Teacher’s Association meeting and his last, and I said, ‘I don’t know whether I needed to have so many years of sitting on the cushion and suffering on the cushion.’ You know? Sesshins were horribly painful, and yet you’d go back again. And he said, ‘Well, I do my meditation now in the hot tub.’ And I still don’t know the answer to that question, whether I really needed – for my own self and personality – to face the suffering on the cushion and just to be with it. I don’t know. As a healer, I go to Tassajara every summer, and I treat the residents and the monks and the students, and – you know – I see a lot of injuries from sitting.”

“This is as a chiropractor?”

“As a chiropractor. As a doctor. I mean, I go as a psychotherapist, and I go with all my toolkit. But especially the young men – you know – there’s a lot of testosterone.” Speaking in a strained voice, “‘I’m such a good sitter I’m not moving even if my leg falls off! You can’t make me move!’ I was never that type of sitter. I was always afraid of hurting myself. And at one point Katherine Thanas, because there was some ambivalence about the forms . . . I mean, coming to our Zen Center is kind of off-putting because some people are such stickers for the forms. ‘No! You walk in with the left foot and then you bow!’ Really, I feel so bad for the new people. But Katherine Thanas did away with the forms for a while. We didn’t have any forms. We didn’t chant. And then we brought them back.”

“Why?”

“I think many people missed the forms. I was surprised that I missed some of the forms. It’s an opportunity for mindfulness. Whatever you’re doing with forms, it brings you into your body.”

“How important is all the Japanese stuff?”

“Very unimportant to me.”

“Then why is it still around, especially with Soto people? Why all these elaborate robes and shaved heads, rules about which foot you use to enter the zendo?

“I don’t know. I think the hierarchy separates, but for many, being a priest is their path of service. I feel you don’t have to be a priest to live a life of service. I think what keeps me with Zen Center is that there’s a sangha of people who love me and appreciate what I teach. Because I think many of the other offerings are more intellectual. Mine is more personal. I’m fairly self-disclosing within reason, and I think that’s helpful for people. And I think it’s important to have my voice and perspective.”

“They need that eccentric aunt.”

“I think so.”