The original Zen (Chan) masters in China were, at times, difficult to access. Their temples were often hidden away in the mountains, intentionally located far from larger population centers. Nor were they necessarily welcoming. Prospective students who found their way to the temple gates could be refused entry for days on end in order to test their sincerity. In the early 1970s, something similar was happening in a remote coastal village in Maine.

Walter Nowick was a Julliard-trained musician who may also have been the first American authorized to teach in the Rinzai School (there are people who question how “official” Nowick’s teaching authority was). After he had completed his training under Zuigan Goto Roshi at Daitokuji in Kyoto, he returned to a farm his family had purchased for him on the Morgan Bay Road outside of Surry, Maine. It wasn’t his original intention to teach, but gradually people learned about him and made their way to the farm.

“The standard practice was to come to the tree in the front yard and stand there for a little while,” Hugh Curran tells me. “I came here in 1975 and stood in front of the tree, and he would send someone out and you would say, ‘I’d like to be a student,’ and he would respond. ‘No. No, I’ve got too many.’ So I came back another time.” Hugh did three vigils by the tree before being accepted.

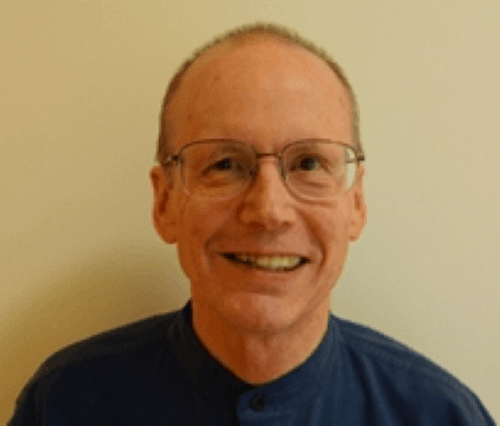

Hugh was my host during my first visit to what is now called the Morgan Bay Zendo. He was born in Ireland and still has the accent. Before coming to Maine, he had studied with Hakuin Yasutani and, later, served for a while as Philip Kapleau’s attendant. Since then, he has also worked with Master Sheng Yen – the Chinese Chan teacher with whom Rebecca Li practiced – and Ruben Habito of Yasutani’s Sanbo Zen lineage.

Hugh’s house is half a mile from the Zendo. The couple who organized that first visit for me – Susan and Charles Guilford – live half a mile on the other side. In the mile between their homes, there are several houses on lots notched out of the thick Maine woods most of which were built by people who, decades ago, had made their way here to study Zen.

In 1984, when the Cold War was still waging, Walter became concerned about the possibility of a nuclear conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, and he stopped teaching Zen in order to focus on trying to promote understanding between the two nations through a shared appreciation of music.

Hugh and Susan and few others formed a board of directors to maintain the Zendo.

“Walter donated the farm to the Moonspring Hermitage, Inc.,” Hugh explains. “We became a religious non-profit. This was facilitated by a member’s husband who was a lawyer in Maryland, so it was incorporated in Maryland. Ten acres had been included which was transferred to the corporation.”

“Walter didn’t have a Dharma successor,” I say. “So you did this with no resident teacher.”

That’s not “quite accurate,” Hugh tells me. “We have myself and Nancy Hathaway [of the Korean Kwan Um tradition]. I would say Senior Dharma Leaders, you could call us.” Later he tells me, that Ruben Habito had “designated me as a facilitator, so I like that term, that I facilitate. Which is pretty much what I do on seminars and everything else.”

He has taught courses on “Ecology & Spirituality,” “Buddhism & Contemplative Traditions,” and “Early Celtic Spirituality” in the Peace Studies Program at the University of Maine, and he has offered retreats at the Zendo, including one on “Zen and Deep Ecology.” Nancy offers training in the Kwan Um tradition. Teachers from other traditions have offered retreats here as well.

Zen tends to be hierarchical, and I find the idea of a community of practitioners coming together to maintain a center without a specific teacher intriguing. For Hugh, it’s a practical matter.

“We ended up being fairly eclectic and tried to suit different people coming here. I mean, in a relatively remote area, far from large urban areas, you have to suit the people that come. And if they say, ‘Oh, well, you guys are into a particular form of Japanese Zen. We’ll go someplace else.’ Or, ‘You’re just a Chinese group; we won’t get involved.’ Or just a Burmese group or this or that. So we try to cover the whole gamut.”

He admits his own approach is still based on the training he had received in the Sanbo Zen tradition. When he is introducing people to the practice, he explains, “I might say, ‘this is a little like the Suzuki method of playing the violin, just learn to play and when questions come up, we’ll work on that.’ Basically, we encourage getting out of the thinking process. Get your mind on the body-mind. Work on moving the attention into the hara.[1] When you’re walking, put your whole focus on each step. Feel your feet sink into the floor, whatever way helps you to get out of the thinking process and into the experience of just walking.”

“To what end?” I ask.

He doesn’t talk about enlightenment or deep spiritual awareness. His answer is quite simple: “To achieve some degree of tranquility, some peace of mind, learn to focus without stress and without nervousness.”

Other links:

[1] A point just below the navel which is considered an energy center in several Asian traditions.