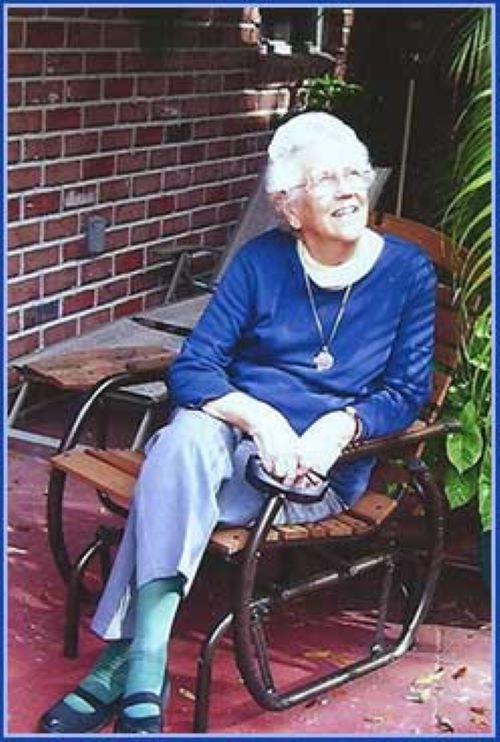

Sister Janet Richardson is a member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace. I corresponded with her in 2015 as I was preparing my book, Catholicism and Zen, at which time I asked if she were retired. She wrote back to tell me: “I don’t think women religious ever retire. I am not gainfully employed now.”

When she had been gainfully employed, she’d worked for a while at the Holy See Mission to the United Nations. “I was the press officer, a member of the United Nations General Assembly Third Committee which deals with social and cultural affairs, and on the delegation to various international conferences.”

She was nearly 50 years old when she first became involved with Zen. “A colleague at Caldwell College asked me to go on a Zen retreat with her. She was a rock of good sense, so I wasn’t going to get into anything weird.”

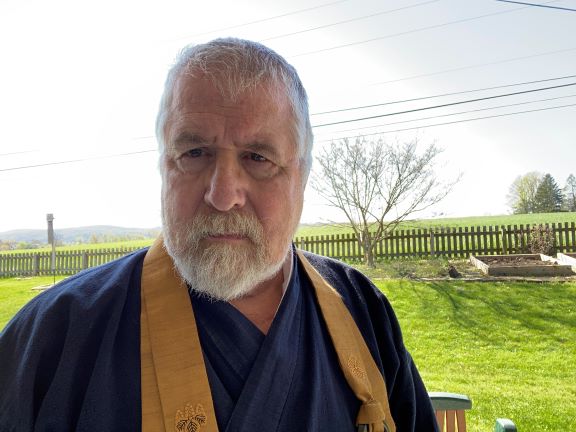

The retreat was led by Robert Kennedy.

“The evening meeting before the retreat began sold me. The topic was Karl Rahner’s work on small communities of prayer in the future of the church. I was a Rahner fan. I never completely understood him, but what I could understand I liked. Our CSJP chapter had committed ourselves to it. We had organized a social development project with the audacious title, Center for Human Development, to respond to the ‘signs of the times’ as we saw them in our neighborhood in Jersey City: families needed food, money for diapers, homeless men came for something to eat. We gathered with groups of the mothers – mostly Latinas and a couple of African-Americans – to pray, to study Paul VI’s Encyclical on ‘The Progress of Peoples,’ and to plan activities to meet their needs as they articulated them. The Center is a fabulous story, I mention it now only to show why Bob’s opening lecture on small prayer groups attracted me.

“As for the retreat itself: Well, you know how painful that first retreat is, how slow it goes. I remember that through the open windows came the sounds of people having fun at the local swimming pool. There were shouts, laughter, the sound of water splashing. The retreatants were facing the wall, and Bob was seated in the middle. It occurred to me, as I sat enduring this, that he had left and was down at the pool enjoying himself. Then the bell rang!”

She recognized that in some way Zen was “something I had been searching for. I shared the experience with the Sisters at home, and we all accepted Bob’s invitation to join his sitting group at St. Peter’s College.”

I asked what she meant by saying that Zen was something she had been searching for.

“Well, spiritual growth is a basic dimension of religious life, and women religious are always getting instruction, going to classes and lectures to that end. Bob’s opening teisho on Rahner was on target, and his approach was the compass here. He also pointed out that zazen was a form of prayer.

“My initial assignment in zazen was to count the breaths to ten and then repeat, being careful not to go beyond 10. Then letting go of the counting ‘since it was a scaffolding’ and just following the breath. When I was introduced to Mu, it repelled me, and I found this practice very unsatisfactory.”

I asked in what way unsatisfactory, and she explained that she felt it was leading nowhere. “Perhaps that was the point, but at the time the discomfort, frustration, and unsatisfactoriness were very negative for me and indicated to me a need for some alternative.” She told Kennedy how she felt, and he suggested she try shikan taza.

Shikan taza is silent, receptive sitting without focusing the attention on any particular support. One is aware of the breath, for example, without having to concentrate on it as in the earlier exercises. It is the standard meditative practice in the Soto School of Zen and is considered an advanced practice in the Sanbo Zen tradition. It is a practice which, following Kennedy, Janet identifies as a form of prayer.

“Prayer is an awareness of God. Bob taught that Zen is a form of prayer insofar as it increases awareness of God. Zen is a discovery path and each of us using the path discovers God as God reveals Herself. The stillness, the awakening to depths and dimensions of an interior life, the presence of others in the same involvement. Sesshin provides samu[1] as an opportunity to collaborate with others who are similarly involved. I remember one of my students telling me that as a Christian, Zen gave her the ‘how to.’ That speaks to me. Was it Yamada Roshi who promised that Zen would make you a better Christian as you emptied yourself as Jesus did? That sounds good to me.”

Catholicism and Zen: 153, 157-66, 167, 189, 196

[1] Work practice, especially during sesshin, in which ordinary tasks – like sweeping floors – become subjects of mindfulness.