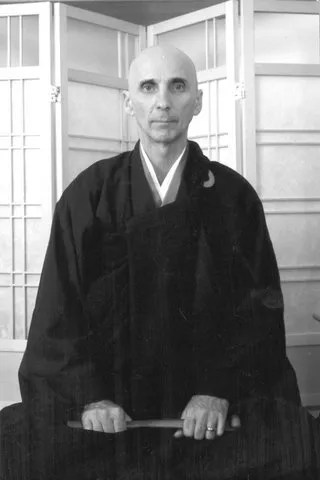

Benevolent Zen Sangha, Providence

James Córdova was a member of the Boundless Way community in New England, which – as he puts it – “sort of split apart, and then I was affiliated with Greater Boston Zen Center for a while, and then we sort of split apart from them, and now we’re doing another thing.”

“So you were part of the group that separated from Boundless Way?” I ask. I didn’t mean the question to imply a criticism – Zen communities are as susceptible to internal conflicts as any other human endeavor – but I did want to be clear.

“Yeah, that split away from Boundless Way and then split away from Boston. We’re malcontents,” he adds with a laugh.

The “another thing” he’s now doing is the Benevolent Zen Sangha in Providence, Rhode Island.

Zen appeals to a fairly narrow segment of the general population. Zen practitioners, for example, tend to be college educated. A surprising number of Zen teachers are academics or psychologists. James is both. He is the chair of the Psychology Department at Clark University and a licensed clinical psychologist. He encountered Zen while a student at the University of Washington.

“There was a professor, Alan Marlatt, an addictions researcher. The University of Washington was full of a bunch of bigshots, so mostly they didn’t teach; they did their research. But if they ever fell into one of these gaps where they were between grants, then the university made them teach. This is what happened to Alan. He was in a gap between grants and so he agreed to teach a graduate course on the Psychology of Mindfulness, which entailed meeting at his house at 7:00 in the morning and drinking overly strong coffee and browsing through his collection of Buddhist books and then sitting on his couches. He would try to teach us how to meditate, and then we would leave borrowing some of his books and hyper-caffeinated.”

“And that got you interested?”

“It did. It really clicked for me. There were aspects of other things that had been compelling to me up to that point, including,” he says chuckling, “existential psychotherapy and radical behaviourism. And there was a long interest in and exploration of – what? – a sort of spiritual quest, I suppose, that I fell into as I fell out of Catholicism and started to engage that journey of filling that space and meaning-making in that particular way. So of all the things I’d encountered, the stuff I was making contact with at that point about Buddhism and about Zen just consolidated it.”

He was working on a Ph. D. and didn’t have time to join a practice group, but he did a lot of reading. “All the big ones, like Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.”

“The Three Pillars of Zen?” I suggest.

“Everybody had to read The Three Pillars of Zen! Right?” he says with a laugh. “The ones that you could find at the university bookstore. So whatever I could find, I gobbled up. There was a sitting group just down the street from me when I was living in Illinois, and I played with the idea of going to sit with them, but I never did. I actually didn’t start sitting with a group formally until I moved to Worcester in 2002.”

“Why were you reluctant to join the group in Illinois?”

“I was an assistant professor and there was the mad scramble for tenure. And I think there’s just enough of the barrier of weirdness.”

Then he got a job at Clarke University.

“When I moved here, one of the promises I made to myself was to try to find a community and to start to get serious about Zen and about practice. I knew this was where Kabat-Zinn had started MBSR[1] stuff, and so I wondered about maybe starting there as part of my research work. So I went to talk to the head of their research arm here at U Mass in Worcester.” He laughs at the memory. “They weren’t so much interested in cooperating on research. They had their research arm pretty well locked down. But as I talked to the guy and we played with some ideas and he was politely ushering me out the door, I said, ‘I’m interested in finding a sitting group here. Do you know of any in the area?’ And he just walked me down the hall and introduced me to Melissa Blacker who was working for them at the time. It was like a warm handoff. He introduced me to her, and we clicked right away.”

He joined the group Melissa and her husband, David Rynick, were hosting at a local Unitarian Church. Eventually he would become Melissa’s Dharma heir, which was one of the reasons I wanted to clarify that he was part of the group which later “split apart” from Boundless Way.

I ask, “What do people get from Zen practice?”

James chuckles and says, “I hope they come away with more of a sense of humor.”

“A sense of humor wasn’t always associated with the early Zen pioneers,” I point out.

“Right? That picture of Bodhidharma just scowling! But I think there’s a lightness, a presence, a playfulness that is, for me, one of the hallmarks of intimacy, one of the hallmarks of a thorough-going coming-to-terms-with, ‘Oh! This is what it’s like to be a human being.’ And there’s a sense of community and a sense of common humanity that comes with that, and the letting-go-of, the putting-down-of of the struggle. Like, it’s a little bit like being let in on the joke.”

“I have a basic notion that the default nature of people is to be happy,” I tell him, “even though I don’t know a lot of people who share that opinion.”

“Yeah, I think there is something to that. There is a joy that bubbles up that has nothing to do with anything.”

“What about koans?” I ask. “Do they play a role in helping people encounter what you called intimacy? Help them become good humored?”

“Wow!” as if surprised by the question. “I think, honestly – this is oversimplifying it – but there is something in koan practice that is exhausting, and I think that’s their function. I think they are that part of our human experience that wants to figure something out. That wants to conquer something. That wants to climb to the top of something. It’s like something I once read about encountering a poem. This poet was saying that people basically want to throttle meaning out of a poem. I can’t remember the exact words he used, but it was sort of like, ‘I want them to drift through it.’ So there is something in the koan tradition that I think ultimately allows us to encounter the koan and meet it as art, as the moment, as something the expression of which is lively and fluid and temporary. And the, ‘What does it mean?’ or the ‘Did I pass?’ – right? – doesn’t matter.”

Further Zen Conversations: 67-68; 75; 80-81; 99; 122-23; 143.

[1] Mindfulness Based Stress Relief