Ring of Bone Zendo and East Rock Sangha

Nelson Foster begins our conversation by telling me, bluntly: “As I’ve said to you before – fair warning – I really think this is a story of Zen communities and organizations, sanghas. Teachers come and go, but the Dharma stays with the Sangha. I see a focus on individual teachers as a reflection of the individualism of our society, which I don’t think has much to do with a tradition such as ours.”

It’s a fair point. But it’s also true that his engagement with Zen came at a significant point in its development in North America, so I kind of twisted his arm to do an interview he was reluctant to do.

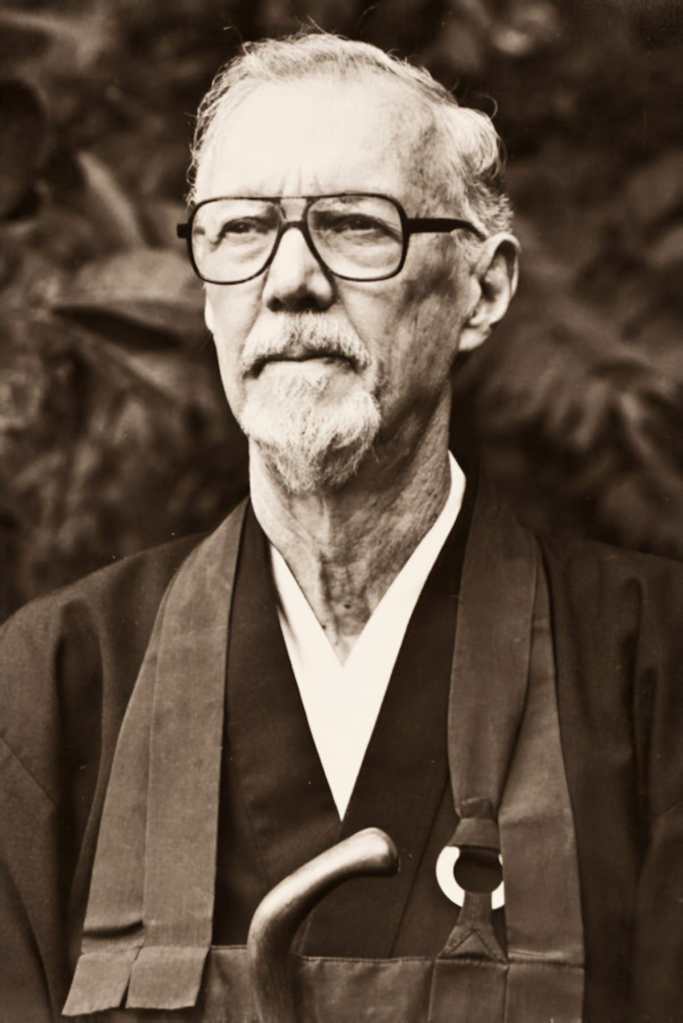

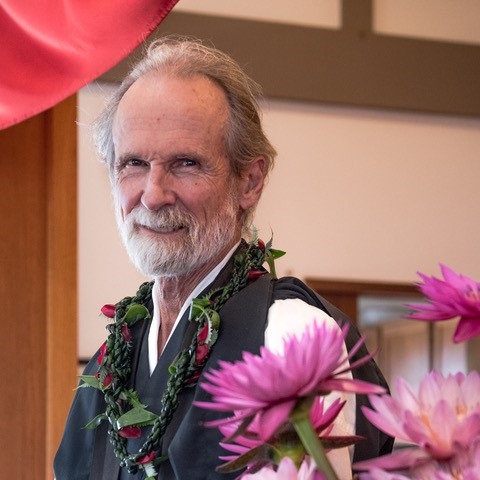

He is one of Robert Aitken’s heirs and has been – since 1988 – the resident teacher at Ring of Bone Zendo in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. He succeeded Aitken as teacher in Honolulu and on Maui in 1997, commuting to and from the islands for the next nine years. Today he continues to work with the East Rock Sangha in New England as well as the community at Ring of Bone.

Nelson grew up in Hawaii, so it was that when he first sought to explore Zen there was a local community to which he could turn. Robert and Anne Aitken’s Diamond Sangha had been established in 1959. Koko An Zendo was in the middle-class Manoa neighborhood of Honolulu, and its membership included people associated with the university, New Agers, professionals, and inquirers like himself.

The history of North American Zen is often presented as if it started with the youth movement of the ’60s and ’70s. But it didn’t. Students – including Gary Snyder and Walter Nowick – who attended Ruth Fuller Sasaki’s First Zen Institute in the early 1950s sat zazen wearing suit jackets and ties. Philip Kapleau’s first students were members of Dorris Carlson’s Vedanta study group who also attended church services on Sunday mornings. Even in San Francisco, Shunryu Suzuki’s initial students weren’t flower children but rather mature women and men who found out about him through the American Academy of Asian Studies.

By the time Nelson showed up at Koko An in 1972, the Aitkens had founded a second community on the island of Maui which was made up largely of folk who, besides being interested in Zen, had also chosen to try out a rural and more “alternative” way of life. Zen – as Nelson puts it – was “in the air.” Suddenly a surprising number of young people (many inspired by their use of psychedelics) were questioning the significance of their lives and were exploring a variety of mostly Asian spiritual traditions they felt might help them resolve the questions they had.

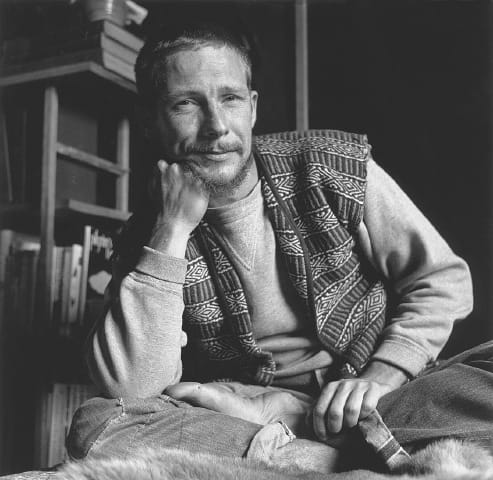

After a summer of intensive practice at Koko An, Nelson completed his bachelor’s degree at Harvard, then joined the residential program at the Maui Zendo. In many ways, he fit right in with the people there, but in others, he was, he tells me, something of a “fish out of water.” He had long hair and a beard and, like most of the Maui sangha members, saw himself as part of a diffuse countercultural movement — appalled by the war in Indochina, supportive of civil rights and feminism, down on consumer habits, feeling largely at odds with the prevailing culture. But during his first full day at Maui Zendo, after quizzing him about his background and interest in Zen, a fellow resident told him, “You’re the first person to come here who didn’t come because of a drug experience.” Nelson chuckles as he recalls this revelation. He also didn’t share the fringier interests of some other residents — fruitarianism, fletcherizing, belief in the lost continents of Lemuria and Atlantis – and other exotica.

The more fastidious Japanese teachers of the time – Dainin Katagiri and Soyu Matsuoka, for example – struggled to conceal how uncomfortable they were with the unwashed youth who showed up at their doors. Matsuoka passed out clean socks to the young people who came to his zendo before allowing them to enter; Robert Aitken did tell Joseph Bobrow to wear a t-shirt that covered his shoulders when he was attending formal zazen but was generally more lenient about such things.

As Aitken became known as a significant figure in the burgeoning American Zen movement, “straighter” students sought him out, and some of the younger enthusiasts dropped away. Others continued their practice but resumed their education, married, had kids, launched careers. Nelson himself, after a stint as personal secretary to Aitken — by then Aitken Roshi — spent his last three years on Maui working as an English teacher. During those years, he joined the Aitkens and a few others in founding the Buddhist Peace Fellowship (BPF) and served as a volunteer to get it up and running.

After moving back to Honolulu in 1979 , he joined the staff of the American Friends Service Committee, continuing his activist career, and in 1981, Aitken asked him to help conduct a sesshin at Ring of Bone. There Nelson discovered a rural Zen community that was, in some ways, very different from the one he’d belonged to on Maui. Most of the sesshin attendees were settled in the area, living with their families on homesteads in the forest, part of an intentional back-to-the-land movement motivated by concern about human impact on the environment and determined to ameliorate the injustices and inequities of mainstream society. Gary Snyder, a leading voice in that movement, was the founder of Ring of Bone and a fellow member of the BPF board. Nelson describes it as a community that lived off the grid “both literally and figuratively,” cooperating out of a shared sense of purpose and with a degree of cohesion that had been missing on Maui.

Nelson would visit Ring of Bone many times over the next seven years, either to assist Aitken in sesshin or, later, to lead sesshin himself. His teaching actually had its awkward beginnings there after a sesshin with Aitken, when two women representing the Zen Desert Sangha invited him to work with their group in Tucson, Arizona. That community – which at the time met in a mobile home – was made up of people who had been associated with Taizan Maezumi’s Zen Center of Los Angeles. As the history on their website puts it: “We had no teacher, little money and it might have appeared from outside that we were unlikely to survive for long. Yet, our hearts were simply open to each other and to the practice.”

Nelson answered that he was flattered to be asked but that he wasn’t a teacher, whereupon the women informed him that Aitken had specifically suggested they speak to him. “That was the first I knew that he thought that I might serve as a teacher,” Nelson tells me. “It was not only extremely informal but really backwards — talking to them before he spoke to me. Bless his heart. That was our man.”

When people at Ring of Bone learned that he’d begun teaching in Tucson, they asked him to work with them as well, and as he succinctly puts it, “One thing led to another.” By 1988, he and his then-fiancée, since wife, had purchased land and an unfinished house adjoining the Ring of Bone property. He has been there now for thirty-eight years.

Nelson expressed gratitude for these decades in their quiet forest home. “Living rurally, off grid makes many demands on your time and attention, but that’s good training in itself, and it makes other things possible. I owe it to this place that I’ve been able to study Chan and Zen tradition in far greater depth than I had previously. It’s not a hideout or a hermitage by any means, but it’s had some of the same advantages.” In his recent book, Storehouse of Treasures, Nelson tells the story of discovering “how thin my knowledge” of his beloved tradition really was. “Chastened by my own ignorance,” he says now, “I kind of started over. Not in my practice, of course, but in the sort of study so evident in the writings and records of our predecessors.” He was at liberty to do so thanks, in good part, to living far from town.

Teaching at Ring of Bone has also brought a dose of what Chan has historically called xingjiao, literally travel on foot, usually translated as “pilgrimage.” The first weeklong sesshin the sangha asked Nelson to lead was what they call a Mountains and Rivers Sesshin, a wilderness event that couples four hours of daily zazen with middays spent walking — backpacking — in silence. Gary Snyder led prototypes of this sesshin form in the late 1970s, and the sangha now schedules two of them annually. “I loved this form from the start,” Nelson says, and he transplanted it to Hawaii during his years teaching there. “I’ve found these sesshin fruitful both as a way of Zen training and as a sangha binder. Leaving behind the safety and comforts of home promotes ‘dropping off’ of other kinds.”

There have been many changes at Ring of Bone during Nelson’s tenure, one of the most significant being a simple result of the passage of time. Some of the people who originally formed the community have moved on, grown too infirm to participate actively, or come to the end of their lives, and leadership has passed to a second generation. A few members are descendants of the original membership and some, but hardly all, live nearby; others attend events from distant parts of California or out of state.

I wonder if what draws people to Ring of Bone today – in the era of MAGA – is similar to what drew people to Zen practice when Nelson had been a young man. “In a certain sense, yeah,” he agrees. “The similarity is that people feel alienated from the majority populace in terms of its values, in terms of its politics, in terms of its respect — its lack of respect — for other beings, for places, for the climate. They feel out of step with its aggressive busyness and are instinctively reaching out for something different, something pointing in a direction that seems to them maybe healthier, maybe more hopeful, maybe better grounded, maybe more satisfying in terms of their own profound questions. I would say it’s a mix of things. Some are people who have bounced around among Zen groups or Buddhist traditions and non-Buddhist traditions. It’s not all back-to-the-landers or a new generation of flower children, that’s for sure. So in that sense it’s rather different from the group that I started out with.”

Each of the groups with which Nelson has been involved has reflected the distinctive character of the communities that formed them. One of the points I have made in my books is that Zen is not a uniform phenomenon in North America but encompasses a range of practices and institutional forms. Ring of Bone, for example, doesn’t have a board of directors, and Nelson does not have an executive position in the community. Elsewhere a resident teacher might carry absolute authority, whereas at Ring of Bone decisions are made through a process akin to consensus which they call coming to “One Mind.” Nelson notes that arriving at this structure and process “took a couple of decades” and fulfills an aspiration that “Aitken Roshi often expressed but never was able to realize” with his own sangha.

There are formal communities where the Asian cultural elements remain strong. There are less formal communities. There are communities – like Morgan Bay – which choose not to have a resident teacher. There are communities which thrived for a while but were unable to survive the passing of their founding members. The communities which continue to thrive, however, are the ones which have the capacity to meet the needs of the communities they serve. So in that sense, Zen is – as Nelson put it – “a story of groups and places. Teachers come and go, but the Dharma stays with the Sangha.”

???? V

LikeLike