Dharma Sangha Centers –

“There was a psychic at Tassajara that I visited with my best friend, Bob, and my sister,” David Chadwick tells me. David is Shunryu Suzuki’s biographer and chronicler of the San Francisco Zen Center. “He was a very powerful psychic, and we’d each gotten readings which were kind of cool. And then we just started asking him about people – you know? – Bob would say, ‘What do you think about so-and-so.’ He didn’t know anything about these people, but he’d go, ‘Boy, is this guy ambitious. He oughta get a motorcycle and ride up mountains.’ But Dick Baker, he said – now, this is 1969 – he said, ‘Here’s a guy who can be knocked down three times and get up each time.’ He said, ‘Most people can’t do that. So he’s a survivor.’ And I tell him he hadn’t really been knocked down, and he said, ‘Well, he will be.’ And that’s what I’ve seen. I’ve seen Dick getting knocked down and always getting up.”

Richard Baker is a central figure in the development of Zen in North America. Elsewhere I compare his role at the San Francisco Zen Center to that of St. Paul in the development of Christianity. His story is often told as something akin to a Shakespearean tragedy: at the age of only 35 becoming abbot of the most prestigious Zen institution in America and then being pressured to resign a dozen years later because of inherent character weaknesses. On the other hand, it can also be seen – as David suggests – as a story of resilience and commitment.

Richard tells me he first encountered Buddhism through his reading, and he developed a romantic idea “of meeting a Chinese Zen Master, but it seemed rather farfetched. I imagined the Zen Master would have a large crowd around him and I would be on the outer fringe of the crowd where I could listen to him and feel his presence. At the same time, I imagined he would only speak Chinese.”

He was in a bookshop in San Francisco with a friend, and the store owner overheard them talking about a samurai movie they were going to see, and he told them they should visit “Suzuki Sensei” on Page Street who was giving a talk that night. They dropped in on their way to the movie.

“I was completely entranced from that moment on. He was great, unfathomable, present, and also beyond – beyond something I knew anything about. I decided almost right away, if he did take students, I would stay with him as long as he lived.”

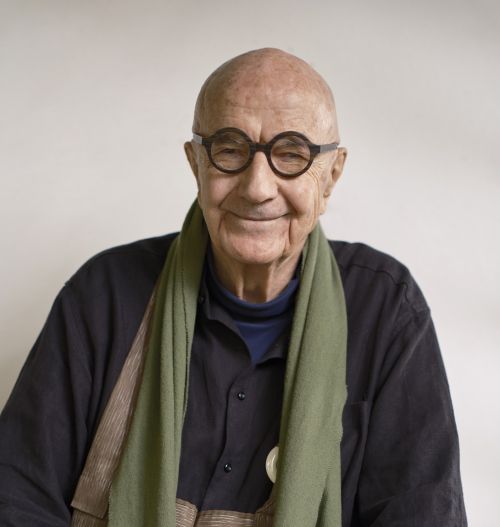

Richard is 89 when we speak and is recovering from a stroke. He has aphasia and occasionally struggles with proper nouns. His Dharma heir, Nicole Baden, is with him and assists him from time to time.

I ask what it was about Suzuki Roshi that struck him so powerfully.

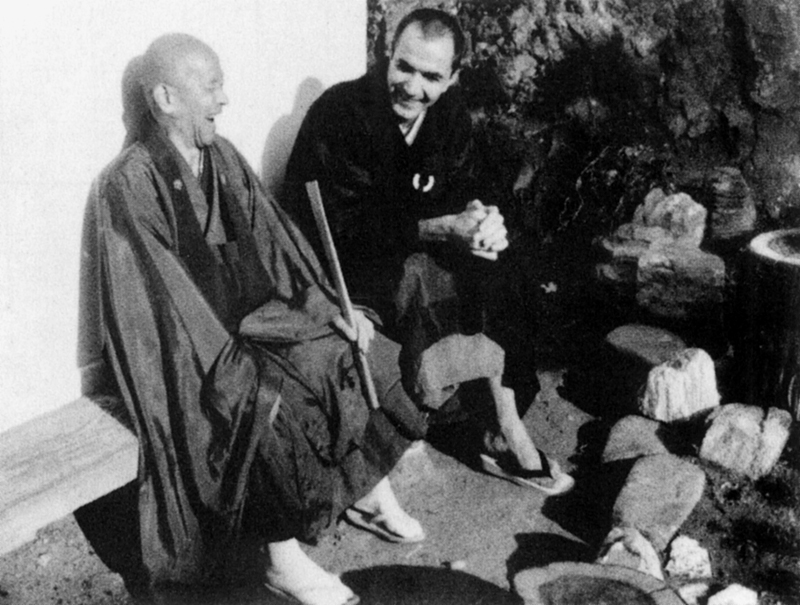

He tells me about a person he’d met while in Iran, where he’d gone with the Merchant Marine after spending three years at Harvard. “Maybe he was a Sufi, I don’t know. He must have been in his mid-30s or so. He was just a totally fine person. I was 20 years old or so, and I always kept in mind that here was somebody who clearly was the way human beings ought to be – compassionate, present, accessible. So when I met Suzuki Roshi, he felt a little like the person I had met in the Near East. But Suzuki Roshi had a whole other level. He was a teacher. He had something to teach. He was a person committed to life. An ideal person, he was genuine and humble. He did not come to teach Zen Buddhism in the USA. I would say he came to teach what Zen Buddhism gave to him. It was a way in which it gave him life. I think that is what he taught.

“From the very first, there was a quality about Suzuki Roshi. There was nothing like it. It was an ordinary humility, just being present. No nonsense. Yet every possibility was present. He was ready with everything. It felt like his presence penetrated all aspects of my life. He seemed informed and ready. Within one day, or the next few days, I decided, ‘This is the most important person I’ve ever met. I will just give my life to him. I will simply do what this person says.’ So every time I did dokusan with him, I said, ‘Whatever you want me to do, I will do.’ Buddhism was very important to me. Zen was very important to me. But Suzuki Roshi was more important than both.”

Suzuki recognized Baker’s commitment and his organizational talents. Nicole stresses that while “Suzuki Roshi’s presence, his particular presence, had a kind of magnetism that created a movement, it took somebody who created the institutional framework to show other Americans of that generation what it is like to follow this person whole-heartedly. So I think Baker Roshi brought a framework that allowed others to follow Suzuki Roshi.”

“Maybe so,” Richard demurs. “But Suzuki Roshi was, for many people, mind-boggling. They’d come to meet him, and right away, ‘This is a sage. This is a person who’s from another transmission. Another way that appeared.’ So, that’s how I felt, and I just stayed with him ’til the day he died. I even feel I am still staying with him today.”

Through Richard’s activity, Zen Center’s growth was staggering. He found the Tassajara site and managed to finance it. He developed the organic farm at Green Gulch. It was inevitable that as Suzuki came to the end of his life and was giving thought to how Zen Center would continue after his death that he should see Richard as his heir and the future abbot. It was, to some extent, a pragmatic decision. According to David there had been other people that he would have given transmission to as well had he been in better health, but in the end it was only Richard who received formal transmission.

The transition, however, turned out to be more difficult than Suzuki could have imagined. As a result of a book about the history of Zen Center published in 2001, a distorted understanding of what happened has emerged. The book implied that Baker was sexually promiscuous with students. To some extent it is a matter of how one defines “promiscuous,” but David – who, in addition to having been Baker’s jisha for a long while, has been conducting interviews with Zen Center members for decades – denies it.

“During my 12-year tenure as the Abbot of SFZC,” Richard admits, “I had three extramarital relationships. These have sometimes been portrayed as dozens; that’s not true. But the number isn’t the point. What I’ve come to understand very clearly is that these relationships were completely inappropriate because of my role regardless of the genuine emotional connection that existed. If I’d been an artist or a poet, it wouldn’t have been such a big deal. But I was an abbot.”

David points out that the more significant issue was Richard’s management style, noting that he was “resented and criticized by his fellow students even before he was abbot.” Richard agrees that there were other reasons people “didn’t like him.”

It was an emotionally fraught period. Soon after leaving Zen Center, Richard visited Taizan Maezumi’s center in Los Angeles. Maezumi was away at the time, and it was Chozen Bays who received him. “Maezumi Roshi and Genpo and Tetsugen [Bernie Glassman] and all the guys happened to be gone,” she recalls, “and it was just us girls running the Zen Center, and so we received Baker Roshi. And I remember very distinctly sitting down with him, me and a couple of other women, and we just had this very down-to-earth conversation. And he said the most interesting thing. He said, talking about the empire he had built and that we had built, and he said something like, ‘You know, everything is impermanent, and it may all come crashing down one day.’ Well, in retrospect, he had left San Francisco Zen Center and was on his way to Tassajara, and everything was coming crashing down, but we didn’t know that. But he said it with such poignancy and emotional depth.”

“Looking back now,” Richard tells me, “if I’d been the person I am today, many of the injuries I caused would not have happened. I had a kind of insecurity and self-importance that I didn’t see at the time. I deeply regret that lack of awareness. It was bad for community dynamics. My behavior caused people to lose their trust in Zen practice. For that, I carry a huge responsibility. For that, I offer my sincerest apologies.”

Although he resigned as abbot of Zen Center, he remained committed to practice and to teaching. At first, he met with a small group of people who remained loyal to him in the Potrero area of San Francisco, then he moved to Santa Fe.

“So,” I ask, “you still felt – what? – an obligation to Suzuki Roshi to keep teaching?”

“There was no question at all. Things happened; everything happened. But even when everything fell apart, the one thing I was clear about was continuing to practice Zen. I wanted to stay with what I received from Suzuki Roshi. This is all I have ever really cared about.”

He maintained the group in Santa Fe for five years, during which time he was also attending meetings of the Lindisfarne Association at their retreat center in Crestone, Colorado. Lindisfarne was a collective of scientists, religious thinkers, and artists who were developing the idea of a new “planetary culture.”

“The people at Crestone couldn’t make it work as a community. They offered it to me in ’83, and I turned it down. Then they offered it again in ’86, and I took it. Lawrence Rockefeller helped me build the Zendo and the Guest House in Crestone. For a while I tried to keep both places going – Santa Fe and Crestone – but eventually I gave the Santa Fe center to Joan Halifax and concentrated on Crestone. One could say I have always been incredibly lucky with people supporting me and with real estate. Crestone is one of the most spectacular sites in the US, ideal, really, for monastic training.”

At the same, he was invited to participate in conferences in Europe.

“Europe in the ’80s was redoing America in the ’60s,” is the way Nicole puts it. “There was a whole circuit. Fritjof Capra, Ralph Metzner, Francisco Varella, Bill Thompson, Baker Roshi and others were part of it. Some of the people from those conferences, like Gerald and Gisela Weischede, came to Santa Fe to practice with Baker Roshi. Later they became Directors at Crestone, and then they started our Johanneshof center in Germany.”

The two communities form what is now called the Dharma Sangha.

“In Germany there are hundreds of people,” Richard says. “In Crestone there are usually five to ten residents: and there are seminars, practice periods, and sesshins twice a year. People come from Santa Fe, Boulder, all over.”

“He’s just talking about residents,” Nicole clarifies. “There’s a larger community around both centers. In order to hold this geographically dispersed community together and also in order to be more active in how to bring contemplative teachings into the world, we started an online platform, the Dharma Academy. At first, we were suspicious of connecting online with people. But as David Chadwick said about Zoom, ‘It ain’t going away, so, you better learn how to work with it.’ That’s the attitude we took.”

Richard is now retired, and Nicole is the current abbot of both Crestone and the community in Germany. But – as David points out – Richard remains active, “He’s full of energy. He has more energy than me. Vision. Indefatigable. Never stops. Right now, he’s not abbot, but he’s still thinking how to keep Crestone going. How to keep Johanneshof going.”

I ask Richard what the role of a Zen teacher is.

“To be fully present with each person. To have a feeling for the movements in them – from their past, their present, and their potentials in the future. And, once in a while, to say, or to do something, which makes people feel themselves in a new context. A context where they can decide what to do with their life. Buddhist meditation changes our mental space. It changes the dimensions of consciousness, changes the loci of self. And through meditation, teacher and disciple discover together a kind of interior consciousness that is not part of our usual way of being.

“At first, meditation is like discovering a window that looks within and without. We can’t really see through the window. We can’t see past the endless forms of self trying to come into better balance. However, we feel something through the window, and meditating keeps this window open. At some point, the student begins to feel that the teacher is beside them, looking through the same window.

“Sometimes the teacher is on the other side of it, planting seeds in a new kind of garden. It takes faith in practice – and in the teacher – before it becomes our shared garden, the student’s garden, the teacher’s garden, and everyone’s garden too, where we plant and cultivate together. That’s my job. To be beside a person at the window. And eventually, to garden together.”

“And the people who come to one of these centers, what draws them?”

“People come for many reasons. Some come because of an emotional crisis or loss. Some come because a friend introduced them and they found they liked meditative sitting. But often, I’ve observed over nearly sixty years, people look for something like Zen practice because they have lost their cultural story. They’ve had experiences – sometimes non-normative, sometimes what you might call paranormal – that their culture couldn’t explain. Sometimes such experiences are locked away. Sometimes they make one crazy. Sometimes they are held in the background, awaiting hints of confirmation. And sometimes that confirmation arrives in the simple act of not-moving in meditation.

“There are also practical reasons. Zen practice gives you a chance to observe, accept, develop, and intervene within your emotional habits and psychological patterns. If your mind becomes freer, more open, more flexible, and more integrated in its functioning, then our deepest intentions and emotions have a wider field in which to play and evolve and change us into the person we feel most satisfied being.

“And then – this is harder to explain – joy returns to ordinary things. Perceiving and thinking return to their roots in appreciation. We often lose touch with such simple things as ease, rest, caring, the sound of birds, a leaf, another person, the shine of water, the sound of rain, the wideness of this spacious earth.

“Growing up, I had grown away from much of the joy I had known as a child. Meditation brought joy back, first as a taste, then as a presence that has become the basis of living. There is a feeling of connectedness with people even when first meeting them, familiarity with situations even when situations are new. You feel you belong in and to this world. You feel at home. This is a direct experience of interdependence, and it is the foundation of compassion.”

At the end of our conversation, he talks about the process of reconciliation now taking place with the San Francisco Zen Center. “It took forty years,” he notes. “But now it seems like it was waiting to happen.

“Nicole initiated the process. She reached out first to the people directly involved, then to the leadership at San Francisco Zen Center. She wanted to understand the whole story before accepting the responsibility of continuing my work.

“And then there has been a generational shift. The current leadership is no longer the generation of the conflict. The new leaders have different intentions. They knew it wasn’t good for either sangha to keep functioning in the shadow of an unresolved conflict. What moved me was the feeling I got from the younger generation: I felt that they expected their teachers to figure this out, to resolve these conflicts, to learn from the past, and to heal wounds that were inflicted. And they were right. If we as practitioners are not able to clean up our conflicts and the harm we create, to learn from our mistakes, to become better human beings, who is? That’s the whole point of practice. If Zen doesn’t help us do that, what is it for?”

“So I am very grateful. I feel there is a realistic understanding of the past. When I had my stroke, it happened at the San Francisco Zen Center, Green Gulch. The people there saved my life. They nurtured me back to health in San Francisco, in the same little apartment where I had accompanied Suzuki Roshi in dying. It’s actually the Abbot’s apartment! So, it was a big honor that Abbot Mako Voelkel of City Center and Central Abbot David Zimmerman allowed me and Nicole to stay in this apartment for two weeks. That’s where I came back to life after my stroke. That time resolved many things. Now it’s a mutual relationship, a real bond. The Sangha at Zen Center treats me and the students from our community like family.”

“There are still people who think your story ended in 1983, when you left Zen Center,” I point out. “What is it that you’d like people to know who are only familiar with that part of the story?”

“Well, I wish they’d know the Dharma Sangha Centers! I don’t care much about my personal story, but I do care about the continuation of the lineage. The main thing to know is my commitment – to Suzuki Roshi and to continuing the Dharma. That never changed. That’s the only story there is, really.”

M

LikeLike