London, Ontario, Zen Center –

Guy Gaudry is the director of the London Zen Center in Ontario. He grew up in a small town in British Columbia – Hope – where he was introduced to Buddhism in a pharmacy.

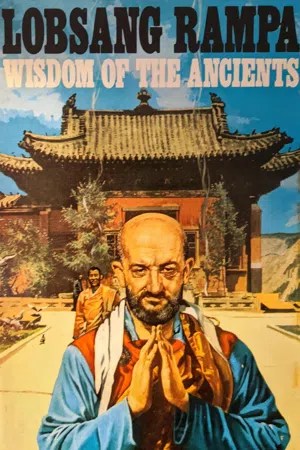

“In Hope, our only source of information was the local drug store. It was a very small and remote town in the mountains of BC. The drug store had a big comic book and paperback section. My friends and I would go there in the evenings to hang out. They would read the comic books, but I always liked to browse the paperback section. It was there that I came across some of T. Lobsang Rampa’s Tibetan Buddhism books, which I found fascinating. They were so different from anything I had ever read before, but I felt a strong resonance with them. I had dreams afterwards about me living a long time ago in a Tibetan Monastery high up on the mountains in a small room with windows that had no glass in them, with millions of stars shining through, illuminating my stone room. Later, I came across a book by D. T. Suzuki – I forget which – but I read it, and I was hooked. And after that, I read every Zen book I could find.”

When he learned about Shasta Abbey in Northern California, he wrote to them. “And said, ‘Hey! I want to become a monk.’ I was so young, keen, and naïve. And I got a nice letter back, and it said, ‘Well, have you talked to your parents about this?’ Right?” We’re both laughing as he tells the story. “‘Well, actually no, I hadn’t’. So I never really pursued it.”

Then life unfolded as it does. He attended the Ivey Business School at the University of Western Ontario, after which he remained in Ontario and set up a software licencing business.

“One day it just occurred to me, ‘I wonder if there’s a Zen Center in Toronto.’ So, I just called up Directory Assistance, and I said, ‘Toronto Zen Center.’ I didn’t even know if the place existed. And they said, ‘One moment please.’ And they gave me a number. I followed up, and I went to my first Zen workshop.”

The Toronto Center was a satellite of Philip Kapleau’s center in Rochester.

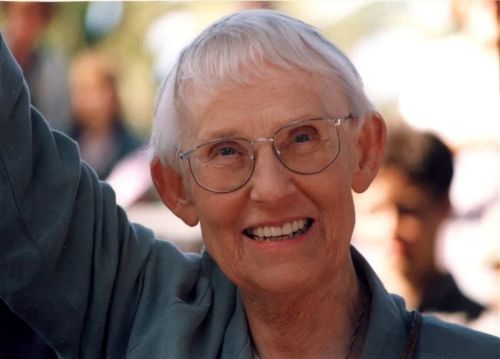

“Then I started going to Rochester for a bit. They had workshops and week-long training periods and stuff like that where I’d go and stay for a week or so. And that’s where I first started to do sesshins. And then I started doing some sesshins in Toronto when Sunyana Graef took it over. Then I started doing more sesshins in Toronto, at her place in Vermont and in San Jose in Costa Rica. I basically traveled to every sesshin she held.”

She introduced him to koan study. “And after five years, I finally got through my first koan, Mu, and I started to go through the curriculum, and then I quit.”

I ask why.

“I was a young guy, I was married, I had a company, I was putting my all my time into my company, and, if I wasn’t working at my company, I was traveling to every sesshin I could. In a dokusan at sesshin Sunyana was asking me some checking questions about Mu, and I was just responding before she even finished. And she said, ‘Okay. That’s it. Why don’t you go onto the next koan.’ And I just stopped for a second, and I said, ‘Oh, no, no. I was expecting much more. I was expecting way more.’ She said, ‘Okay, okay, we’ll keep working on this.’ But during the rest of the sesshin, as I sat, I thought, ‘There are all those koans waiting for me.’ So, I started working on the next koans, I got up to number seven, ‘Wash Your Bowls.’”

The seventh case in the Mumonkan tells of a monk who comes to Zhaozhou and informs him that he had just entered the monastery. Zhaozhou asks, “Have you had your breakfast?” The monk says he had. Zhaozhou tells him, “Wash your bowls.”

“Anyway,” Guy goes on, “the rest of my life had started falling apart, and I went to Sunyana and told her this, and I quit Zen. I had become disillusioned with koan work and needed to focus on the other parts of my life. I stayed away from Zen for about five-years. What I got from Sunyana, however, was a bit of her amazing work ethic.“

“So, essentially you quit Zen, and things get better,” I joke.

He laughs. “Yeah. I stopped Zen, and I just started paying attention to work and relationships. I said, ‘My head’s too much in this Zen stuff, I have to look after my life.’ Eventually I came across Joko Beck’s book, Everyday Zen, and – whew! – what a completely different approach to Zen from what I had been doing. I fell in love with her just by reading her books. So, I went down to see her, and I worked with her for a very, very brief period of time. And I told her my story, and she said, ‘The type of Zen you were practicing is harmful.’ I felt I was talking to a wise mother. She said, ‘That’s not a healthy practice for you. You have to focus on your life, your actual life experiences.’”

However, when he told her that he would like to work with her more formally, she demurred. “I said, ‘I want to work with you. I get what Zen’s supposed to be now, or at least I have a better understanding.’ She said, ‘Well, I’m in San Diego, and you’re in Toronto.’ She said, ‘That’s a long way to fly all the time. Why don’t you go see Steven Hagen in Minneapolis. He’s the real deal, and he’s closer to you.’ So, I said, ‘Okay’ and went and saw Steve. And he was an exact opposite of my previous teacher. He’s a big Norwegian guy and had a traditional Soto practice. His teacher was Dainin Katagiri. It was a very quiet, peaceful and warm practice. I think he comes from a family that includes a long line of Lutheran ministers. The first time I saw him in dokusan, after introducing myself, he said, ‘Guy, it’s so nice to meet you.’ And I felt that was sincere. I felt the warmness of his heart. It was genuinely warm. It was a very different feeling for me in Zen. So, I stayed and sat with Steve for another five/six years. And after a while Steve said I should start doing some teaching, and I started a Zen sitting group back in London.”

Although he’d passed Mu and other koans with Sunyana, he still had not had the type of experience he had been expecting.

“’Cause you’d read the book,” I suggest. “You’d read The Three Pillars of Zen.”

He laughs heartily. “I’d read the Three Pillars enlightenment stories. And my experience wasn’t quite at that level of intensity. I had talked to Joko about that. Joko didn’t put much emphasis on those types of experiences. She put more emphasis on daily practice, and realization in the moment. Steve also was very solid. He said, ‘Don’t worry about the flashing lights and bells. Just keep sitting.’ So that’s when my life started getting really better. I sat with Steve for around five years. Stopped all the koan work; I was just sitting, doing shikan-taza. There were many long, painful sesshins, just dealing with myself and no koans.”

“Psychologically painful?”

“Yes, psychologically painful but they were also physically tough too. When you had the meals at Steve’s sesshins, you didn’t get a break from sitting. They just served the meals on a little tray they put in front of your cushion. Hard on the legs! But I settled down. My life started settling down. I was getting back into focus. My whole life had settled.

“One of the last sesshins I did with Steve was led by Shohaku Okumura, a Dogen scholar. He was very Japanese. I remember when I first saw him in sesshin, and as he walked by me it was like he was floating above the ground. I hadn’t seen anything like that before. He talked about the Shobogenzo during his teishos. It was a five-day Dogen sesshin. Near the end of this sesshin, a quote in one of Steve’s books – ‘If you could just realize there’s no connection between your senses and the exterior world, you’d be enlightened on the spot’ – arose in my mind. I was, ‘What’s that really mean?’ So, while Shohaku was talking about Dogen, I just held that quote as a koan, since I knew how to work with koans. I held it very intensely; time disappeared. On the last day of sesshin, this koan opened up for me. I was enlightened on the spot, Kapleau-style plus. Now I was satisfied! Every single koan I had ever read became super clear to me. I could easily answer any koan. It was all so clear! I went and saw Steve, but I could tell he didn’t know what to do with me because he was not used to working with koans in this way.

“Months later, the next time I saw Steve, I said, ‘I’m going to go finish my koan work with John Tarrant. This is unfinished business for me.’ And he said, ‘Yes. I think you should do that. I don’t work with koans in that way, but you’re in a place where that would be helpful.’ I did a couple more sesshins with Steve and then headed to PZI.”

Then he adds, “One thing I skipped over, during that time I was working with Steve, I went through Jungian analysis. There was a great, brilliant guy here in London who I worked with. After that, I started doing some Jungian training at the Toronto institute; And also, the other thing was that during my time with Steve, I went to Art School. My business was doing well, and I had some free time, so I went back and got a fine arts diploma at Sheridan College in Oakville. I started writing, painting, and learning photography art; I was deep into art. I loved art, I loved Jungian psychology, and I loved Zen. And I then found John Tarrant: Art, Zen, Jungian psychology. Wow! This guy is made for me.”

I ask him to tell me a John Tarrant story.

“Well, while one time in my early days at PZI, I was sitting in sesshin, and dokusan was going on. I wasn’t in dokusan, but I could hear people going in and out of dokusan room. Then I heard a big kafuffle coming out of the dokusan room, which was followed by someone stomping away. I whispered to the person next to me, ‘What the hell was that?’ And she says, ‘That’s just John’s dokusan.’” He laughs. “I knew he had a different approach and saw, or heard, firsthand that he moves in deeper places than most teachers.

“Another time we were in a teacher’s meeting, and it came up that I had broken protocol as Head of Practice because I had bowed to a woman during my morning greeting who wasn’t working as a leader in that sesshin. I thought I might be in trouble, but then John said, ‘That’s why I like Guy; he’s not afraid to break protocol.’”

John made him a sensei and his group in London began to develop. For a while, the London group worked with koans in the way that John’s Pacific Zen Institute do.

“So the koan groups became quite popular in London. People were coming. Then I developed a koan group for psychiatrists in Toronto. One of the psychiatrists who had come to one my workshops asked if I would host a koan group for her colleagues in Toronto. I did that for two years and it was a lot of fun. I think they found the Zen and Jungian mix very appealing.

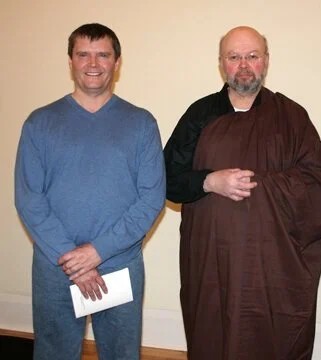

“I kept doing sesshins and worked closely with John. I had started teaching at PZI, started hosting dokusans at PZI sesshins, and I worked with David Weinstein a lot. The Center in London continued growing; I had John come to London for workshops which people really liked. Then John gave me Dharma Transmission and I became a Roshi. John came up here for the Dharma Transmission ceremony in London. I remember it was February. It was freezing cold. The ladies at our Centre made ice candles and placed them all around the porch at the centre. John and I were guided into to the Center by ice candles on that dark and cold winter night in Ontario. The ceremony was very warm. And then afterwards we drank Japanese whiskey late into the night.”

“So now you’re a roshi,” I say.

“Yeah. Yeah.”

“You enlightened yet?”

“Well,” he laughs, “I have a different idea of what enlightenment is now, but I do know of that place they talk about. But more often than not I am stuck at the bottom of a well. That’s the way it goes. That’s the practice part of Zen, stepping out of holes. I learned that from Joko. She didn’t really care if you were enlightened as long as you were constantly moving back towards the place of awakening.”

Guy no longer uses the PZI “koan salon” approach.

“You can get a lot of low-hanging fruit with group koan work. You can get people to have small little glimpses. But I watched people who had done these koan groups, and I could tell they weren’t getting any lasting or deep insights. They were getting small little hits, little bits of insight and openings, but they weren’t really developing as a human being in the Zen sense. So, I think people in other lineages saw this and said, ‘This is an abuse of the koan process. Because those other lineages don’t introduce koans until you’ve been sitting for a long time and have developed some discipline, some insight, and some stability, and then they move into koan work. So that’s why some other Zen lineages didn’t like the koan salon approach. They thought it was an abuse of the process. It was like offering low-hanging fruit at the expense of a greater integration.”

On the other hand, he points out, “Not everyone’s going to do Zen work. Not everyone’s going to have the discipline or the drive or the ability or the gumption to sit down and do some serious Zen work, learn to sit for a while and build some discipline. So, the koan groups are going to reach people who are not going to do that. At least we can give them something.”

I ask about the approach he currently takes to teaching.

“Well, we do traditional Zen – zazen meditation – so . . . We actually sit more than PZI does. So, you’re gonna do some zazen. Some structured sitting. You’re going to have an opportunity to work with a teacher, one-on-one.”

I ask what is the purpose or value of the sitting?

“That’s how we can start to grow and clarify who we are. If you do want to develop in terms of human growth – as a human being – you have to do some work. If you are feeling bad or anxious or afraid or disjointed or alienated, and if you truly want out of that, a drug or a quick fix isn’t going to help. You’ll have to do some work, and that’s what we do here.”

“So it’s a matter of human development?”

“Human development. Personal development. Which is the hardest thing. A famous Harvard psychologist said, ‘The hardest thing in the world is adult human development.’”

“So what good will it do me? What am I gonna get out of it?”

“If you want to experience the world differently and respond to the world differently, then Zen might help you. A lot of people come here because they want help or to be enlightened or whatever, but they go running out twice as fast because they realize its hard work. If you’re feeling anxious, you’re going to have to sit with anxiety for a while. Or if you’re feeling alienation or darkness you have to learn to sit with that for a while, and then we can start exploring a path out together.”

I ask how he sees his role as a teacher in this process

“I’m still trying to figure that out. I think I’m becoming more of a confidant to people who are deep into this work, people who are walking deeply on the Zen path, and who want to explore what it’s like to live an awakened life. That’s one thing the koan curriculum does, you get to explore this awakened world from all different angles and learn how to move in it.”

??

LikeLiked by 1 person