Seven Thunders –

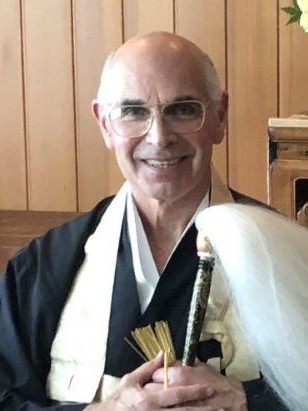

Leonard Marcel is a founding member – and current teacher – of Seven Thunders Zen Sangha in Portland, Oregon. He is also a retired psychiatrist and Jungian analyst. He grew up in Brooklyn, ten blocks away from Bernie Glassman’s home neighborhood. “We never knew each other, and, of course, he died a few years ago, but we were about the same age.”

He was raised in a Catholic family and still goes to church. “But not in the same way. So Catholic background, Catholic education. Had the nuns in grade school and the Jesuits in high school and college and medical school.”

I ask if it meant anything to him.

“It did. I valued that education and that upbringing in a particular tradition. I think it’s important for children to have an upbringing in a particular tradition even if they don’t agree with it and rebel against it. It gives them a basis for values and for how to live. They can do what they want with it later, although as Jung pointed out, if one moves away from one’s natal tradition, it is important for emotional health in adulthood to resolve any unfinished conflicts related to moving away.

“I also valued the emphasis on the eucharist as the ‘real presence,’ the Christ-spirit present and alive in each person. And so I took that with me as I was growing up. At the same time, there was something missing. It wasn’t enough.

“Another thing I really liked about my childhood experience of Catholicism was that as an altar boy we had First Friday adoration. And I loved when the church was dark and it was just the candles and the Blessèd Sacrament. And there were two of us young kids – took turns, an hour at a time – just being there in silence and stillness. That spoke to me very deeply. It was my first experience with something akin to meditation. I think, when the time was ripe, that experience moved me on the path towards Zen.”

His introduction to Jung – and the inspiration for his career – came when he was 17 and still in high school. “The Atlantic Monthly published a series of pre-publication excerpts from C. G. Jung’s Memories, Dreams, and Reflections. And there was a candystore/soda shop near our house where I often went to get sports magazines and things like that. So, I was standing there in front of the newsstand with all these magazines, and I see this on the bottom row, and it sparks my curiosity. So,I started reading it. I read the whole article standing there. I came back the next month and read the next article. And I thought, ‘That would be a fine career, a fine way to help people and make a living.’”

After high school he went to the Jesuit-run Georgetown University and followed that by attending medical school in Omaha. “Creighton, which was also run by the Jesuits.”

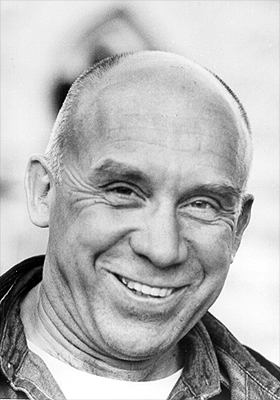

He first learned about Zen through the Trappist monk, Thomas Merton.

“You may recall that in those years – ’50s/’60s, at least until ’68 – Thomas Merton was well-known worldwide and certainly within the Catholic community. So, I knew that there was this thing called Zen out there and that Merton had been attracted to it.”

But it was not yet something he felt drawn to. Then in 1980 – while he was in private practice in Portland – “I had a patient who said to me, ‘My father goes out to the Trappist abbey for his retreats.’ I thought, ‘Hunh! There’s a Trappist abbey around here. I never knew that.’ So, I started going there. It’s forty-five minutes from Portland, a Cistercian Abbey, Our Lady of Guadalupe. I started making private retreats there whenever I had a free weekend. And after three or four of those, the guest master said, ‘You know, with your interest, I think you’d like to meet our abbot.’ And this was Bernard McVeigh. And Bernard was the one who invited Robert Aitken to come and lead the first sesshin in Oregon in ’79. Bernard was very interested in Zen, and so I met Bernard, and we became good friends. And he invited me, when I was there, to do zazen with the monks at 3:00 in the morning before their first service in the church. So that’s how I came to Zen, through Merton and through Bernard McVeigh.”

The draw – as when he had been an altar boy – was sitting in silence. I ask what it was about that that attracted him.

“I cannot put it into words. It was something very profound. Very deep. It was a clearing away of the busyness of the mind and touching something beyond words. There was something powerful in the silence and stillness, something foundational.”

In 1984, Abbot Bernard announced that a German Benedictine monk and Zen Master, Willigis Jäger, was going to lead a Zen sesshin in Portland, and he encouraged me to go.

“So, I went to sesshin with Willigis. And by the morning of the third day, my legs were killing me.” He’s laughing as his speaks. “And I said to myself, ‘You’re not going to get out of here alive.’ But I looked around, and there were sixty people, and they all seemed to be sitting like little stone Buddhas. I didn’t know that they were all thinking the same thing, but I said, ‘If they’re not gonna leave, I’m not gonna leave.’ And you know how it is. The second half of a sesshin always goes more smoothly. And then you start thinking about, ‘When’s the next one?’ That’s how I got started.”

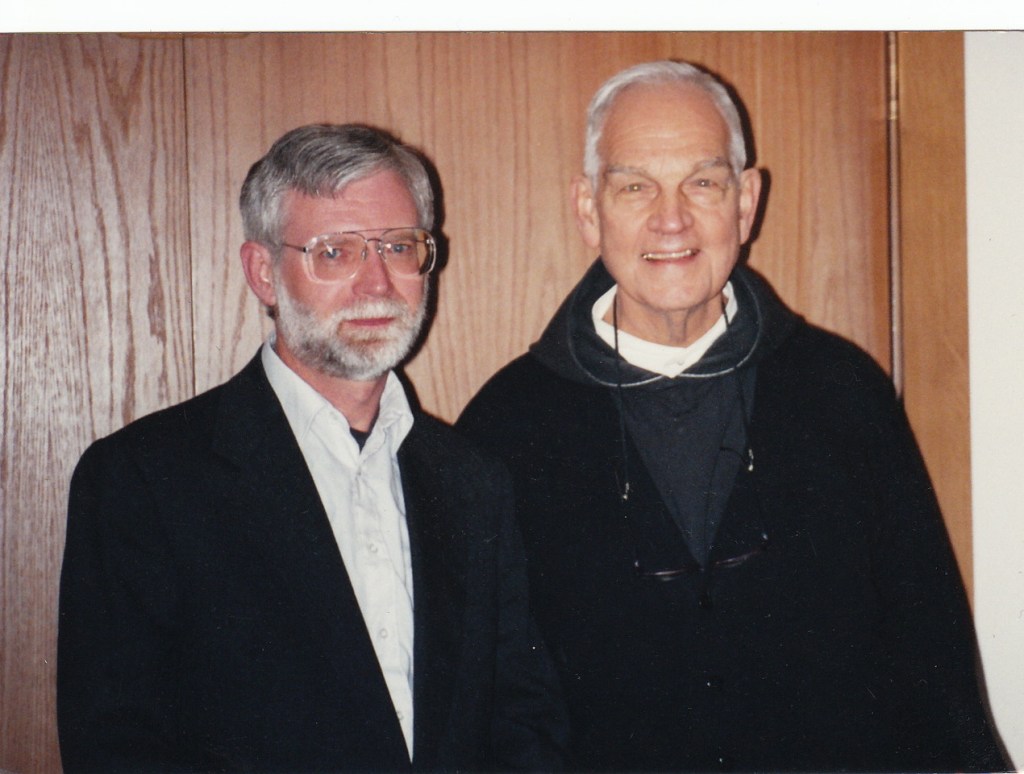

Willigis came to the Pacific Northwest regularly, leading both retreats in Catholic contemplative prayer and Zen. By 1987, however, he was so busy in Germany it was difficult to continue the American visits. So that year he brought Pat Hawk with him.

“Pat was not the Zen Master that I had in mind. He was from a different mold. He was quiet – a man of few words – but he always was right to the point. He had a delightfully dry wit.” Willigis turned responsibility for his American students – Leonard included – over to Pat. “And I became Pat’s first koan student.”

“Was that at your initiative or his?”

“It was at his. I didn’t know what a koan was. I was just a happy Zen student going along. I had a busy medical practice. I was doing this, and it seemed to be enriching my spiritual life. I liked koans, always have, but it took me a while really to get the presentational aspect of koans. They were engaging, and I felt, ‘There’s something here that I want to get, and I can’t get to it in my usual way.’ You know, we professionals often have lots of trouble with koans because we are so left-brain oriented. D. T. Suzuki once said that koans are something that keeps the mind engaged while something more important is going on under the surface.”

After Leonard had spent a couple of years travelling to Seattle to attend retreats with Willigis and then Pat, Abbot Bernard suggested he should consider establishing something in Portland.

“Bernard was in contact with all sorts of lay people – for a cloistered monk, he knew more lay people – so he said to me, ‘You know, there are a lot of people around here who would like to sit together more than once a year with Willigis.’ He said, ‘Why don’t you get them together, and, if you do that, I’ll give you a place here in the monastery where you can sit.’ A couple of weeks later I called a few people, and we had a little organizational meeting, and started sitting at the Trappist Abbey in August of 1985 – we just had our 40th anniversary – sitting on the first Saturday of every month for contemplative prayer practice. That was the beginning of the group that has subsequently become our Seven Thunders Sangha. So that group started forming and gradually increased in number. And because Pat and Willigis were both Catholic priests and Zen Masters, we’ve always had dual programs for spiritual practice. We offer Christian contemplative sittings on the first Saturday of every month, and we do two Christian intensive retreats – several day retreats – twice a year. And we do weekly Zen sittings and zazenkai and sesshin. But we do not combine the forms. Some of our members just follow the Zen Buddhist program, others the Christian contemplative program and still others, like myself, are ‘crossovers’.”

Then in 1992, Leonard left the United States.

“I had been the representative from Oregon to the General Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association in Washington DC. In that capacity, I would go back to Washington three times a year, and we’d have our meetings, and then I would come back and report to the members of the Oregon Psychiatric Association. In going back to Washington, I got to know people at APA headquarters, and knew one fellow who contacted me in 1992, and he said, ‘How would you like to work in Saudi Arabia?’ And I said, ‘Oh, well, probably not.’ And he said, ‘Well, let me tell you about this. The Saudi Arabian Oil Company has a big medical center. They have a lot of Western ex-patriot employees. They’ve been asking for a Western psychiatrist. They’ve opened up a new position. I think you’d be a good fit.’ So I went to Pat, and I said, ‘This has come up. I’m not sure what to do.’ And he just very directly said, ‘They need you.’ And so, I sold my practice to one of my office colleagues, and I went to Saudi Arabia – I thought it would be a year or two – just to have a change of pace and assess the need. I was there for ten years. I would go back to Amarillo or Tucson – after Pat moved there – and I would sit sesshin with him at least twice a year. And in-between times we would carry on our koan work by phone. This was before Zoom.”

He explains that the oil company had been looking for someone to work with, “the Western employees and their families. It was the usual mental health problems: anxiety, depression, marital difficulties, whatever, and so the Western employees were asking for someone of their own culture.”

I express surprise he was able to maintain his practice with Pat throughout this period, and he tells me he even started a small sitting group in Arabia. “Mostly for Westerners, and it was very much an underground group because there’s a lot of sensitivity in Arabia about other religions. So sometimes people would come to me and say, ‘I hear you have a Zen Buddhist group.’ And I would say, ‘No. It’s just a meditation group.’ The Saudis were okay with meditation. They could see that as part of general health care. But if we called it ‘Zen’ or anything to do with Buddhism, that was not acceptable. Eventually, from this group, a coterie of serious American practitioners coalesced, so that we were able to have weekly zazen and monthly zazenkai there. A few of those people have continued attending Seven Thunders events over these thirty years.”

During one of his visits back to the United States, Pat asked him, “‘Are you taking notes on your koan work?’ And I said, ‘No. Should I be?’ He said, ‘Well, when you’re on a teaching track it’s a good thing to do.’ And I said, ‘Am I on a teaching track?’”

“It was a surprise to you?” I ask. “Was it something you were open to?”

“I wasn’t quite sure what it was going to entail, but it seemed to me that it was important, and, if he felt I had something to offer to people, not just as a clinician but as a spiritual guide, I wanted to see what that would entail and to what it would lead.”

He began to attend Diamond Sangha Teachers’ meetings, and through them met Rolf Drosten, a teacher from Germany who is one of Robert Aitkens’ Dharma heirs. “He invited me to co-lead sesshin with him in Germany twice a year, which was very generous of him and was an important part of my teacher training. We did that from 1998 to 2003. In 2001, Pat came to Germany to perform a final transmission for me. In 2003, I came back to Oregon. Now by this time, Pat had been diagnosed with the cancer and was slowly declining. So, when I came back, I began to assume more of the teaching responsibilities at Seven Thunders.”

I have interviewed several Zen teachers who are also therapists or analysts, and I inevitably ask them to define what distinguishes the two traditions.

Leonard tells me, “Koun Yamada Roshi, my great-grandfather in the Dharma, said that Zen is ‘perfection of character’ and that is exactly correct. I would add that it is also to help a person find out who he or she really is beyond all the roles we all play; beyond all the ways one has defined oneself over the years. And to clear the mind and heart from all that has been sticking, from all of our self-centered concepts and cherished opinions, so that an experience of the ultimate dimension – what Buddhism calls ‘emptiness’ – may be possible.

“Psychotherapy is to help you resolve any conflicts, difficulties, complexes you may have, and in the process get to know yourself better. While psychotherapy helps to build and strengthen an ego-self, Zen requires taking the further step of relinquishing that artificially constructed sense of self in order to experience the interconnectedness of life.”

“Okay,” I say, pursuing it a little further, “if I came to you as a Zen teacher, what am I most likely looking for?”

“We are all suffering. We are all wounded in some way. Some people are looking for a spiritual path that they’ve never felt comfortable with previously. Some of them are looking for whatever it is they think ‘enlightenment’ is. Some of them are looking for just a way to feel more centered and at peace.”

“And if someone comes to you as a psychiatrist, what are they looking for”

“Ways to resolve their conflicts or the patterns that keep repeating in their lives or the relationship difficulties they keep getting into, or help with recurrent depression, or ways to deal with anxiety. Some have more serious mental health problems that require medication in addition to psychotherapy.”

For Leonard, Zen is “the foundation of all religions. I think it is that from which all religions spring.

“You view it as something more than a sect of Japanese Buddhism?”

“Yes, It is a sect of Japanese Buddhism, but Zen in its purest form is foundational.”

“Something universal?”

“A universal source for a life of faith, a life of upright centeredness, a life of a bright awareness to the interconnectedness of all existence.”

I want to make sure I’m not misinterpreting him. “So, a kind of innate capacity or potential in people? Every dog has Buddha nature?”

“Yes. I think everybody is called to a Zen life or a contemplative life. Most people don’t pay attention to the call, but I think it’s there in each one of us.”

“What has this practice done for you?”

“It gets me back to basics. Just this straight back. Just this breath. Just this moment. This is the only moment in which I am alive. If I am not present to this moment, where is my life? It’s not an hour ago when we started talking. It’s not tomorrow. It’s only right now. That is the purity of Zen. Apart from all the doctrinal and metaphysical teachings. Right here. Right now. It has also given me a clear way to live an upright life that is helpful to others.”

“And if right here, right now I am miserable. I’ve got cancer. My wife has left me. The bank’s foreclosing on my house. My dog died.”

“Yes. And every day is still a good day. How is that so?”

We both laugh.

“As a teacher,” I ask, “what is it that you hope for for the people who seek you out?”

“That they will awaken to the true nature of reality and who they really are.”

“And what is it that they hope for from you? What do they look to you for?”

“Well, I’m sure a lot of them look to me for the answers. So, I always point them back, and I always say, ‘The answer is inside of you.’ How sad that people ignore the near and search for truth afar, as Hakuin tells us. What I hope for is that they will learn to trust their own experience and stand on their own two feet.”