Atlanta Soto Zen Center –

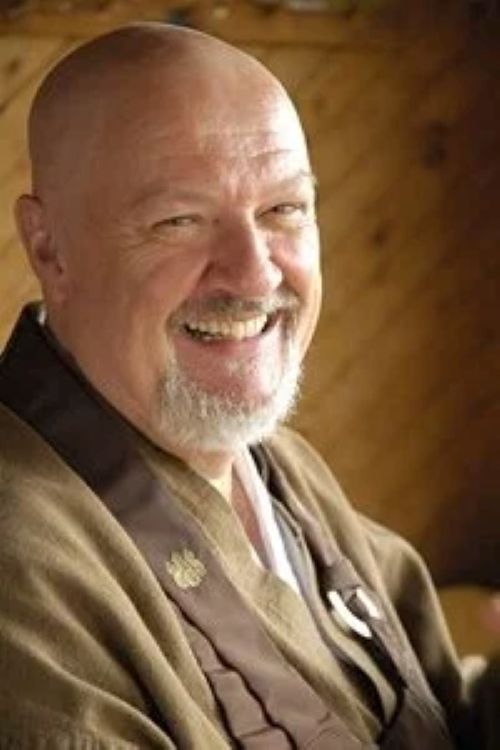

Taiun Michael Elliston is the founder and guiding teacher of the Atlanta Soto Zen Center in Georgia.

He grew up in Centralia, Illinois. “Named after the Illinois Central Railroad. Due east of St. Louis, about 300 miles south of Chicago. Pretty much in the middle of the state,” he tells me.

His family weren’t actively religious, although, “They would drop us off at Sunday School. I actually went through baptism. I had some friends who were in the church. They went through baptism, so I went through baptism.”

I ask if it meant anything to him.

“Not as much as it meant to them. One guy, a friend of mine, became very emotional. So it was obviously deeply meaningful for him. Then an incident came about where you were expected to tithe, to bring in some kind of donation that you could afford. I think I was bringing fifty cents or something, and one time I couldn’t. We didn’t have enough money for me to take it to church, so it was a little embarrassing. And the teachings were strange for me. It was all just belief-based, of course, and it was a story about reality, a creation myth and all that. And it was like – you know – that could be true, but it just seemed very remote.

“We lived on a small farm – 20 acres – and had a barn and some sheds. We didn’t own the place; we rented it. And there was an opening between all the buildings out back which was overgrown, almost like a jungle, vines and everything. My sister said she’d come out there, and I’d be sitting on a chair in the middle of that space just staring into space. I was standing on my head and walking around on my knees with my legs crossed, just getting into yoga as a 6/7/8-year old without knowing what it was. So I spent a lot of time in isolation. Anecdotally, folks who are recognized as being creative, having careers in the arts, seem to share this trait, a lot of time alone as a child. You learn to entertain yourself.”

Michael is a visual artist. His brother and father were jazz musician. “Jazz was very big before rock-’n’-roll came along,” he reminds me. “My brother was very well known in Chicago; he played all the big jazz clubs there. So he had a lot of musician friends, and the LSD revolution was happening. And one of his drummer friends and I were talking, and I mentioned LSD, and he said, ‘Oh, I don’t do that anymore. I just do Zen.’ And I said, ‘Well, that’s interesting. Tell me about that.’ And he said, ‘Why don’t you come this weekend? I’m going this weekend.’ So, I went with him and met Soyu Matsuoka Roshi, my teacher. And, as we say, the rest is history. I hadn’t read much about Zen. I’d read a little bit. But I was impressed by his warmth and his friendliness. His down-to-earth-ness and so on.”

Michael became a regular attendee,

“What you did when you came in, you had a place to put your shoes and things. It was a railroad apartment, and what would be the living room/dining room was the zendo. The altar was against the far wall of the dining room. And the baths and kitchen and his bedroom and stuff were in the back, and there was a back porch – typical railroad apartment, brownstone three storey walk up – and afterwards we’d sit back there and have tea, and he would talk a little bit; he would answer questions. It was mostly guys about my age. It was also hippie-dippy time, and Matsuoka Roshi would meet us in the vestibule by the door with a basket of clean socks. Because you had these – he couldn’t understand this at all – you had these guys walking in off Halstead Street bare-footed walking into his carpeted living room to learn meditation, sitting on his cushions with their filthy feet and legs. So there was this big basket of white socks, and he’d give each person a pair of socks to put on before they could come in. He was very fastidious, like most Japanese. And some of the Western American attitudes just really astonished and repelled him.”

Michael was studying Bauhaus Design at Illinois Tech at the time, and he discovered that Zen made a lot of sense in that context.

“Bauhaus was a design school set up to humanize the outputs of the industrial revolution. The whole foundation – the first-year approach – is immersion. You are immersed in certain media like stone, clay, plaster, wood, drawing, painting. In that way you sort of absorb the way in which physical media work.”

Meditation, he recognized, was another form of immersion. “So immersion in consciousness as a medium, I recognized that it was something familiar. ‘Oh! That’s what we’re doing here. I see what we’re doing.’ The theory is that if you sit still enough, straight enough, long enough, your own consciousness will start to break down. It will deconstruct. This is common in Zen teaching; the reality that we experience is actually a construct of the mind. And the only way to get past that construct is to sit still enough, straight enough, for long enough. The closest thing to sensory deprivation that they would have had back in India or China or Japan and so forth. As the meditator sits facing a blank wall, everything starts to break down. And so I could see it started happening right away. All those methods in the Bauhaus about training the senses had a one-to-one correlation with Zen.”

Fairly quickly Matsuoka recognized that Michael was someone he could rely upon.

“I started taking on teaching assignments. The schedule was Sundays, 10:00 and 2:00; there’d be two different groups coming, 10:00 in the morning and 2:00 in the afternoon. And then Tuesday and Thursday evenings. And that was it other than special meetings. We’d go out – he’d speak at the YMCA – he liked me to accompany him. He could see I’m articulate. He’d bring me to the public talks, and I would field the questions. The Q & A at the end. He liked the way I answered the questions; he wasn’t that comfortable with that kind of dialogue. He would give the talk, and he wrote them out so that he could read them in his thick Japanese accent.”

Then one day in 1967 or ‘68 – “Just before I moved to Atlanta, Matsuoka Roshi took me aside and, said, ‘You must become a priest. Not for yourself, but so that others will listen to you. We live in a credentialed society. If you don’t have credentials, no one will listen.’

“So I said, ‘Okay,’ and we did my ceremony. We did a discipleship ceremony, and later a priesthood ceremony.”

In 1970, an employment opportunity took Michael to Atlanta. When Michael moved to Georgia, Matsukoka turned the Chicago community over to his heir, Richard Langlois, and moved to California.

“I was only with Matsuoka Roshi in Chicago from the beginning 1965 to 1970 when we both left. It was a little over a five-year stint in Chicago.”

I ask how he established the Zen community in Atlanta.

“There were places in Atlanta that were dedicated to offering such programs. I found a big house in a residential neighborhood, where they had rooms dedicated to things like yoga classes, where I began offering meditation sessions. It was kind of informal. So after some time floating around from place to place, I went to the Unitarian Church on Cliff Valley Way, the biggest Unitarian Church at that time in Atlanta. And somehow I found out that they had a Buddhist study group. I don’t remember all the details. Sure enough they were happy with allowing me to start a sitting group. In a church, you typically find rooms full of furniture. I would push the furniture back, clearing a space, carrying big garbage bags full of zafus in for the sitting, and taking them out at the end, right? Set up; take down; repeat. Until, after some time, they give you your own room because enough church members are now participating.

“By 1975, I had a regular group of Zen followers. We were meeting in lofts and storefronts, places like that. We found a little corner shop in the Candler Park neighborhood where the owner had a jewelry shop in one part of it. There was an area that used to be the service bay – it had once been a service station – and that was our sitting room for a long time. It was a room something like 15 x 15 feet square. Later we moved to the location where we are now. where we have a larger zendo connected to two small bungalows.”

Michael admits he was fairly isolated from other Soto teachers at the time because Matsuoka had ceased supporting the Soto-shu in North America and, as a consequence, his Dharma heirs were not registered in Japan. But, as Matsuoka put it, we live in a “credentialed society.” So Michael took steps to regularize his situation with the help of Barbara Kohn of the San Francisco Zen Center and Shohaku Okumura who was located in Bloomington, Indiana.

“Barbara Kohn had students in the southeast inviting her here. When we moved in 2000 to the new space, I invited her to use our space, so she started coming there, and her students would come. She did a couple of my interim ceremonies there, the novice priest or black robe ceremony called Shukke Tokudo.” When she learned Michael was not officially associated with the Soto community in North America, she offered to help. “She was very practically oriented, very down-to-earth. She said, ‘Well, we can fix this. You should be recognized. You should have credit for time served.’ She started putting it all together. I went and met Okumura Roshi in Asheville at a friend’s house, hosted by one of our members from Candler Park days who had moved to Asheville. Okumura Roshi was visiting Asheville, giving talks on translating poetry derived from Dogen’s poems about the Lotus Sutra. And he was asking us for suggestions on the translations. I had attended a talk he gave in Palo Alto, so he and I knew each other vaguely by the time Barbara talked to him about me. She talked to me about going through the transmission ceremony on a formal basis, and training in the advanced ceremonies, or priest protocols which she called forms. She said I should go spend a 90-day practice period at Austin Zen Center with her, in the middle of the summer of 2007.”

It wasn’t feasible, but Okumura stepped in and agreed to do the ceremony. It was Okumura’s intention that Michael – as he put it – not “do anything to break off the Matsuoka line. He said, ‘If you go back to Japan and train under another lineage, that cuts off the Matsuoka line.’ So what he did for me by doing my transmission ceremony, as I understand, does not cut off that line. I still represent the Matsuoka line – lineage – but at the same time I am also in the Sawaki-Uchiyama lineage through Okumura.”

Okumura came to Atlanta for seven days to conduct the ceremony. “There’s a seven-day version and there’s a twenty-one-day version, in Japan. We opted, naturally, to do the seven-day version. He was in residence for that whole week. I painted the large silk certificates, during that week. Fortunately I’m trained in design, so it was easier for me than for most candidates. You have to paint on silk with water-base sumi ink – black and vermillion – lines and names. Fine lines in red without blurring and blotting, with ink, on silk!” He laughs at the memory. “They can’t make it any harder.”

Michael is in his 80s when I speak with him, an age at which even Zen Masters begin to think about retirement, but he is still active.

“I lead workshops. I lead daily meditation and retreats. Just came back from a five-day retreat in North Carolina. We have a hundred-acre farm, a farm one of my senior students owns. He’s a prison psychiatrist. His wife is a yoga teacher, a licensed yoga teacher. We have four events a year there, roughly a week long. Four or five days. Every fourth Sunday is my morning to teach at the Zen Center. First Sunday features guest speakers from outside our lineage. Second Sunday we present interviews; I interview a member from inside our community, typically a leader-type person, but not necessarily. Third Sunday my eventual successor at ASZC gives a dharma talk. We have a vice-abbot and a co-abbess who will assume leadership in Atlanta. We just think that everybody should get to know what kind of people are practicing Zen. Why they’re practicing Zen, why they keep coming back, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.”

I ask why they do keep coming back.

“I think it is, first of all, real life. The point I make is . . . Do you know what the kyosaku is?”

I do. It is the stick which meditators are sometimes struck with on the shoulder.

“So my point is that you either get the kyosaku in the zendo under controlled conditions or you get it out there under uncontrolled conditions. So I think what forces people back is getting whacked by the vicissitudes and vagaries of circumstance that are our daily fare in the 21st century.”