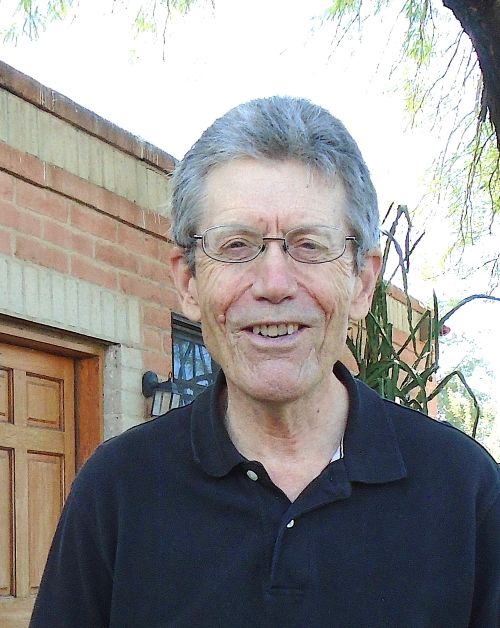

Zen Desert Sangha –

Dan Dorsey is the resident teacher at the Zen Desert Sangha in Tucson. He grew up in Texas, and first encountered Buddhism in the library at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches where he was studying forestry. “There were only three books in the library on Buddhism, and I read them all. Don’t remember the titles. I was one of those people who at an early age was drawn to Buddhism and meditation. In my apartment I constructed a sitting bench made from concrete blocks and a flat wooden board and started doing zazen from reading the instructions in one of the books.”

I ask him why.

“Maybe karma; it’s a mystery to me why some people go into Buddhism at an earlier age and others take it up when they’re seventy. At first, I thought there must be some benefits that would accrue to me personally – like strength, better control of my emotions, inner power, and inner peace. I think I watched too many kung fu movies in my teens where that kind of self-mastery seemed to be the point of meditation. In a deeper sense though, from an early age there was this feeling that there was something fundamentally wrong with life. Not just the ups and downs, but a very deep feeling that something wasn’t right with all the suffering people go through – the wars, starvation and economic inequality, the person-to-person violence – everything I read about in the daily news.”

His first encounter with formal Zen practice was in Japan in 1982.

“The U.S. Army put me through four years of college in exchange for me serving as an officer for four years of active duty after graduation. As a new officer, I could choose a number of places where my first assignment would be if there was an opening, so I chose Japan because Buddhism was practised there. I was also interested in the culture. There was an open position with a small Army detachment on the northern tip of the main island of Honshu near the city of Misawa, so that’s where I went.”

“And did you, in fact, come upon any Buddhists in Japan?” I ask.

“There are plenty of people in Japan who identify as Buddhist, just like in the U.S. there are plenty who identify as Christian. There are plenty of Buddhist temples and shrines around, but it took a while to find a place where zazen was practised even a little.”

He did, eventually, find a Soto temple where if he made “a donation to the temple, then the monks would sit a round of zazen with me, and I could have tea with the head of the temple for about fifteen to twenty minutes. Even after months of searching around northern Honshu, I could not find a temple or lay group that kept a regular schedule of zazen, aside from one or two small monasteries, and those were not open to the public.”

Then he was transferred to a base outside Tokyo, and there he saw an article in the newspaper announcing that a Soto priest, Sensei Gudo Wafu Nishijima, welcomed both Japanese and foreigners. “I started sitting with his group. I would take the train every Sunday morning into downtown Tokyo to where we met on the eighth floor of the YMCA. The schedule was each Sunday Sensei would give a Dharma talk to his Japanese students, then his foreign students like me would arrive, and we would all sit together for two rounds of zazen. His Japanese students would then leave, and Sensei would give his talk in passable English to us. When he did retreats, he borrowed a Soto temple.”

First retreats are always challenging and probably even more so in Japan. “I found them difficult both mentally and physically. Although I had been sitting fairly regularly for 25 to 30 minutes on my own each day, I still sometimes used a chair instead of a cushion. There were no chairs available at the temple, and the cushions were small, flat, and firm. I found doing round after round of zazen to be difficult.

“At the same time, there was something about sitting still for round after round that drew me in. We’re in a society where doing something about the situations in our lives is highly prized. It’s encouraged to be proactive. And this was really the first time I had sat for longer periods with just myself, not doing anything except sitting, turning inward instead of outward. I was also getting a small inkling of what true peace is. I experienced something at those retreats and that kept me coming back.”

During his final year of active duty, he was stationed at Fort Huachuca near Tucson. “There was no Zen group there, so I continued practice on my own and stayed in touch with my Japanese teacher via letter correspondence. After being discharged from active duty I moved to Tucson.”

There he came upon a group that had just formed about 18 months earlier.

“There were five or six of us sitting in a mobile home at a trailer park. One small bedroom was converted into a Zendo. The group had already adopted the name of Zen Desert Sangha.” The group was affiliated with Robert Aitken’s Diamond Sangha, and Aitken’s heir, Nelson Foster, visited the group several times a year. Aitken also visited occasionally.

The sangha changed locations a few times and then, “We ended up at Indiana Nelson’s big blue house in an upper-class section of Tucson with a good sized Zendo. It was at that time that Pat Hawk Roshi started coming to Tucson a few times a year and giving retreats. That’s where I met him and became his student.”

After being discharged from the Army, Dan earned a master’s degree in Landscape Architecture then became certified in Permaculture. He was able to combine his forestry degree with these and began a business providing workshops and courses on sustainable landscape design.

He tells me he also was dedicating more time to his Zen practice. I ask why he kept at it.

“Well, one thing that’s kept me going is the alternative to not practising is worse. If you know what I mean,” he adds with a laugh. “Thinking on how I could have turned out if I didn’t keep up a steady Zen practice makes me shudder. I was driven to do it. Maybe it’s karma. I just stuck with it from age 20 or so. Once I found Zen teachers to work with, the practice naturally fell into place and has stayed with me.”

Then in 2010, Pat Hawk invited him to have coffee at the Redemptorist Renewal Center where he resided. “And he asked me if I would be willing to become an Associate Teacher in the Diamond Sangha. After considering it for two days, I called him and said, ‘Okay. I’ll do it.’ I was already giving classes on Buddhism before I became an associate teacher because no one else was giving them at ZDS at the time. Preparing for them helped me to understand Buddhism in more depth. Pat was fine with me doing this. At the time, I was also teaching some non-credit classes on Buddhism at a community college in Tucson. I had already been studying with Pat for sixteen years at that point. After some consideration, it seemed like the natural next step.”

He became an Associate Teacher in the Diamond Sangha in 2010 and then a fully independent teacher two years later.

“And what does a Zen teacher teach?” I ask. It is a question I frequently ask.

“As far as individually working with students, I’m there to facilitate and encourage their practice, point out pitfalls they might fall into, and support them in practice through all the ups and downs. I give pointers along the way and try to offer the right phrase or action at the right time. However, I don’t think Zen can be taught in the usual sense.

“Zen has no end, since there is no end to Zen practice. We say at our Zen Center that the Buddha was only half-way there. But we as teachers can point students toward experiencing their own true nature through their own efforts. The Sangha plays a big role in this also; we support each other. I sometimes say, ‘You’re not going to get anything from Zen.’ But other times I’ll talk about the benefits of practice, the ‘fruits’ of doing zazen as an expedient if someone needs encouragement.”

“Which benefits are those?” I ask.

“I’m still waiting for most of the benefits myself, but based on studies using brain scans and other techniques, regular and long-term zazen calms the central nervous system. Also, the part of your brain that deals with reactivity and how quickly we automatically react becomes a little larger. That seems to have the effect of calming our reactions. We don’t react as quickly, which can help with various drug additions and also calm routine and damaging expressions of emotions like anger.”

“Those are physiological benefits. Are there spiritual benefits?”

“I can’t separate the two exactly. Spiritually if Zen has a purpose, it is to allow or make more likely the experience of our true nature – experiencing the emptiness of it all. Although I like the phrase ‘no abiding self’ rather than emptiness. And I also emphasize experiencing true nature as a process rather than one all-encompassing life changing event as many people imagine it will be. So, this sitting practice of zazen is both experience of and inquiry into that true nature or no-abiding self.”

“And when people first take it up, what draws them? What are they looking for?”

“They’re looking for a number of things. They want to get rid of their suffering, which is a universal experience. They want to get some benefits from meditation to help in sports or martial arts. They want to get rid of specific uncomfortable emotions like anger and learn to stay calmer. Some show up with a genuine will to discover the truth.”

The Diamond Sangha derives from Sanbo Zen and makes use of koan study. I ask about the value of working with koans.

“Koans function to get a person out of those extremes that we’re always caught up in. Right and wrong. Life and death. This and that. Me and you. So, what transcends that? Koans are usually a back and forth between the relative world and the empty one. When a person comes to a master in a koan, he’s coming from one of those places; the teacher answers from the other side. And then finally, what transcends that? The student has to do a presentation at that point to show that right here and now. Sometimes words will work too. The main thing is the presentation has to be a personal presentation within the context of the koan and not too general.”

In his own continuing development, Dan is in regular contact with another Pat Hawk heir, Leonard Marcel. “We talk once a week when we are both available via Zoom, and we do a review of koans. We’ve gone through additional books that might be used after the standard Diamond Sangha curriculum of the four classic koan books. Right now, we’re finishing The Recorded Saying of Layman P’ang.”

“And the reason you do that?”

He answers with a shrug. “To explore new Zen books I might one day use with my students and to keep sharp on koan practice with another Diamond Sangha teacher.”

“And how has your practice changed over the years. How is different now from when you were first going to the 8th floor of the Tokyo YMCA?”

“My practice is more integrated into everyday life. There is more openness to this moment.”

🤩

LikeLiked by 1 person