Maitri Compassionate Care –

Issan Dorsey died thirty-five years ago on Sept 6th, 1990, nearly a quarter of a century before I began this pilgrimage into the landscape of North American Zen. What I know about him comes from reading, especially David Schneider’s biography, Street Zen.[1] For me, Issan is a stellar example of a contemporary Bodhisattva.

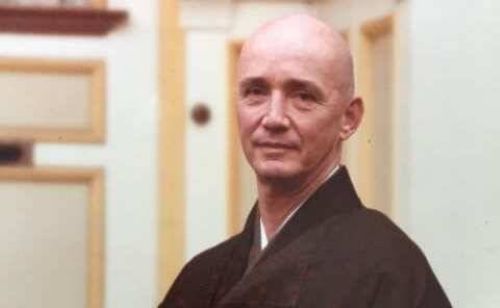

Doubtless he was the most unlikely person to earn the right to be addressed as “roshi.” Tommy Dorsey was a drag performer, heroin user, and prostitute who once described being raped in prison as “rather interesting.”

He engaged in a lifestyle that was exciting but dangerous. Twice he almost died from drug overdoses. He engaged in the San Francisco gay scene wholeheartedly but was also known for demonstrating a deep compassion for those who were less able to navigate those waters safely.

After surviving an accident in which all the other people in the car died, he was given LSD by a friend who treated the drug as something sacramental. The friend also introduced Tommy to meditation and chanting, and Tommy joined a psychedelic-centered commune on California Street in San Francisco. Over time, the commune degenerated into a messier hard drug scene, and Tommy began doing speed.

On Christmas Eve 1967, his younger brother was the only person in a car crash to die. The contrast with his own accident struck Tommy sharply. He stopped doing speed and had a sudden sense of personal accountability for both the people around him and the physical and social environments. He surprised the people who knew him by taking on responsibility to police the Haight Asbury neighborhood for trash.

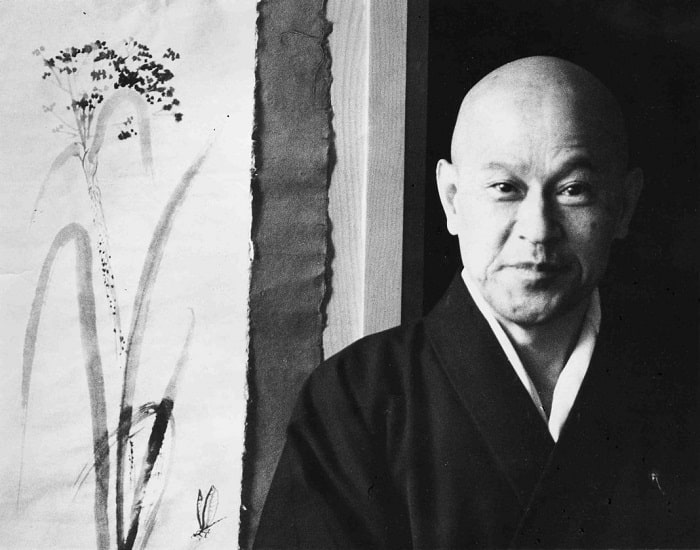

Eventually out of curiosity – and because it had become a popular destination for many – he came to Soko-ji, the ethnic Japanese temple where Shunryu Suzuki was teaching Western kids how to meditate. Tommy was charmed by Suzuki and spoke without embarrassment about loving him. Suzuki had that type of charisma, but Dorsey was also someone who loved others easily. Their coming together led to a major transformation of Dorsey’s life.

Tommy left the commune and moved closer to Zen temple. He threw himself into the discipline of practice. And when the non-Asian Zen students separated from the Japanese temple and moved into their own place on the corner of Page and Laguna Streets, Tommy moved into residence there. In 1970 he “took the precepts” and formally became a Buddhist. He was given the name Issan Dainei – “One Mountain, Great Peace.” For people who were unsure how to pronounce his new name, he told them it rhymed with “piss on.”

Suzuki had cancer when they met and died in 1971. But before he did, he asked Issan – and his other disciples – to accept his successor, Richard Baker, as their teacher and address him by the formal title, “Roshi.” After some initial reservations, Issan did as he was asked. He even formally became an “unsui” – or monk – in a ceremony with Baker which included a profession of loyalty to his new teacher.

Baker came to value Issan as someone whom he could trust to carry out the responsibilities entrusted to him without fuss and with good humor. He assigned Issan to positions of more and more responsibility. In 1977, Issan became the head monk – or shuso – at the San Francisco Zen Center’s remote mountain monastery at Tassajara. This, in effect, made him Baker’s second-in-command at Tassajara, and it was recognized that the position was a preliminary step towards eventual transmission.

In 1980, a group of gay practitioners came together at Zen Center to discuss issues of common concern. Zen as a teaching is intended to guide people to an experiential understanding in which all human beings are recognized to have the inherent capacity to experience awakening; however, there can still remain challenges for people who do not belong to the majority population. As a teacher in Boston once explained to me, “There is a real difference in the sense in which one can feel secure and relaxed and open if one’s been a part of any kind of marginalized community, a difference between being in a community in which one is or is potentially marginalized by other people in the group and a group in which you feel that you can let that guard down.”[2]

Issan joined the group, which he referred to flippantly as the “Posture Queens.” The group called itself “Maitri,” the Buddhist term for friendship. They eventually moved out of Page Street and established a separate center on Hartford Street. By 1981, it was formally inaugurated as an affiliate zendo of the San Francisco Zen Center, and Issan was appointed its “spiritual advisor” with Baker’s support.

Richard Baker was an extraordinary man in many ways, and he took what had been a fairly small religious community with annual revenues of around $8000 a year and transformed it into a multimillion-dollar enterprise. But he also had what many thought of as an imperial manner, and in 1983 the situation became such that Baker was pressured by the SFZC board of directors to resign as abbot.

The community split after Baker’s resignation, but Issan – remembering his promise to Suzuki – remained loyal to Baker and went with him when he relocated to Santa Fe. However, in his absence, the discipline at the Hartford Center declined. One resident suggested it had become “a collection of gay men living together in the middle of the Castro district who keep a pet zendo in the basement.”[3] They petitioned Baker to send Issan back, and he did so, appointing Issan the center’s Teacher in Residence

As the resident teacher at Hartfold, Issan was called upon to lead retreats for gay and lesbian people, and provide other services, including funerals. And the funerals began to become more frequent. The situation was dire. There were support services for people with AIDS, but, as Schneider put it “ – on the street level, the gutter level, the level on which Issan himself had spent most of his life – the care was very flimsy indeed.”[4]

Issan by now was also HIV positive, and he saw all around him people who were gravely ill but who had no resources or support systems in place. They were, in effect, homeless and dying in the street.

In November 1987, he arranged for one of the members of the Hartford Center to become a resident. The man had AIDS-related dementia and peripheral neuropathy, which meant that he needed help to move about. Doctors estimated that he had less than six months to live. The only apparent option was for him to go into a hospital, where conditions tended to be sterile, where he would be kept from contact with others. Issan envisioned something more humane, a homelike environment where the dying could feel loved and supported and were able to continue to interact with others. And as it happened, with the care he received at what was now called Maitri, the patient rallied and lived longer than expected.

Other end-of-life patients were invited in. The gradual transformation of the Zen Center to a hospice was not universally approved of. Some saw the proximity to the dying emotionally distressing. But Issan had been taught by Suzuki that all that occurs provides an occasion for practice, including one’s last days and the care others could provide at that time.

Issan formed a board of directors; he found a medical director. He organized fund-raising. The place next to the Hartford Zen Center was bought, and the patients were housed there. They avoided the term “hospice” because of the legal ramifications, but Issan knew what he was creating. “What we are doing is renting rooms to people who need twenty-four hour care and who are in the last six months of their lives.”[5]

Former Zen students came to assist. For some, ironically, it was their way of finding their way back to a practice they had fallen away from after Baker’s departure.

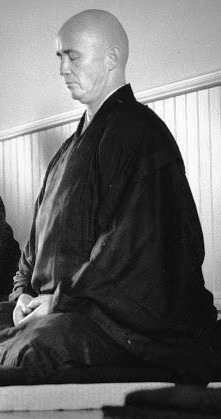

Baker remained supportive of Issan and in November of 1989 a formal ceremony full of archaic ritual and fancy robes (“I’m still wearing a skirt,” Issan said, “just not the heels”) was held in which 57 Hartford Street was declared to be a temple – Issan-ji – and Issan himself was elevated to the rank of abbot. The ceremony was briefly interrupted when a patient fell out of bed and Issan had to excuse himself to help the person off the floor.

Issan would not be abbot for long, but he did live to see a successor take his place as abbot. His health deteriorated throughout 1990, and that May he was diagnosed to have AIDS-related lymphoma. The pain levels were excruciating as was the treatment. Issan had gone from being a caregiver to a care receiver.

Two months before his death, Baker took him through another ceremony in which he was given full teaching authority and could claim the title “Roshi.” Baker insisted that it wasn’t something he did out of sympathy. “If he did continue to live, he would have been a great teacher.”

The Hartford Zen Center still exists and promotes itself as “a Soto Zen temple for the LGBTQ+ community, friends and allies in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood.” Maitri Compassionate Care – no longer on Hartford Street – also continues to operate and has expanded its work to offer care to people going through transition. Their website states: “The heart of our work is our Residential Care Program, which provides medical and mental health care to people in need of hospice, 24-hour respite care, or recovery support after gender affirmation surgery.”

Issan’s death was difficult, but there were flashes of genuine grace right up until the end. John Tarrant recounts a story about his last days, by which time he needed assistance to go from one place to another. “A friend was helping him come back from the bathroom. They paused on the first-floor landing. The friend, a person himself so fiercely nonconformist that he was nicknamed ‘the feral monk,’ was overwhelmed by feeling, a previously unheard-of event. He took a deep breath and said, ‘I’ll miss you, Issan.’ Issan turned his large, liquid, seductive eyes on his friend and said, ‘I’ll miss you too. Where are you going?’”[6]

[1] Shambhala, 1993.

[3] Street Zen, p. 160

[4] P. 168

[5] P. 174

[6] John Tarrant, Bring Me the Rhinoceros. Boston: Shambhala, 2008, p 80