Memories of Robert Aitken –

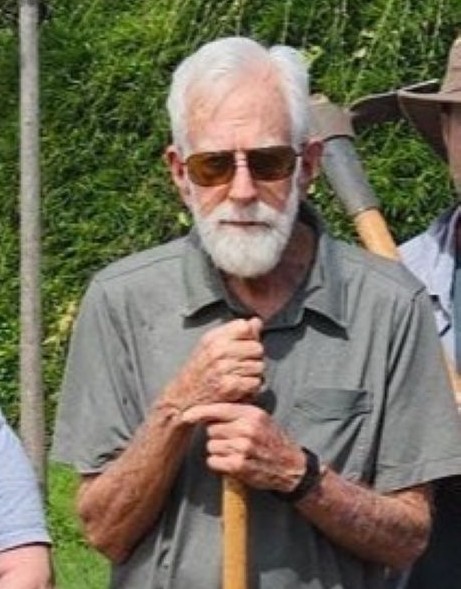

“I’ve been a member of the Diamond Sangha since 1966 when the term referred only to the group practicing in Honolulu,” Don Stoddard tells me. “Now the term embraces groups in many places around the World.” He had also been personally involved with much of the construction work that took place over the years both on Oahu and Maui.

Don was born in 1937 – a decade earlier than me – and first learned about Zen in the 1950s. “When I graduated from high school a friend of the family gave me a copy of a small, hardbound book called, Buddhism and Zen which was a collection of pieces translated, compiled, and edited by Nyogen Senzaki and Ruth Strout McCandless. It was originally published in 1953 by the Philosophical Library and reissued in a paperback with a foreword by Aitken Roshi a few years ago. So, this was given to me in 1955. I read it through, and it was my first taste – you might say – arousing an interest in Zen. Then, when I was between my sophomore and junior years in college, a collection of D. T. Suzuki’s essays came out in a Viking paperback edited by Bill Barrett.”

In 1960, he was in graduate school but decided, “I’d had enough years of going to school. In those days eligible males faced the possibility of being drafted if they were not in school. The military obligation was ten years. There were various ways of dealing with it, but, for me, the most appealing way was to join the Navy, go to OCS, become an officer, do three years of active duty, and then the seven remaining years would be in the reserve. It happened I had a choice in what type of ship I would be assigned to and what home port. So, I called my wife, who was still in North Carolina where I’d been in school, and asked, ‘Where would you like to go?’ And we decided on Hawaii.

“When I completed my active duty, I stayed in Hawaii. I was already practicing Zen a little bit on my own based on my reading. One day at a Honolulu bookstore there was a copy of Philip Kapleau’s Three Pillars of Zen. I bought it and read it through and thought, ‘There must be other people here engaged in this practice.’ I checked a couple of the established Zen Buddhist Temples, but there was no sign of an active zazen practice going on. I wrote to Philip Kapleau care of his publisher telling him my situation. Very quickly I got back a postcard and it said, ‘Contact Robert and Anne Aitken. They’re in Honolulu.’ With a phone number. I called the number right away. Anne answered. I told her what I was looking for, that I had been sitting on my own, and was looking for a group to practice with. She said, ‘Well, we’re sitting tonight. Why don’t you come up early and speak to Bob, my husband, and he’ll talk to you and show you what the forms and procedures are.’

“Koko-an, the Aitken’s home in Manoa valley, was about a fifteen-minute walk from where I was living. I went early, met Bob, told him I’d already been doing a self-assigned Mu as a practice, and he said that was fine. At that time there were public practice meetings on Sunday and Wednesday evenings. However, every weekday morning the front door would be open at 6 a.m.” Don got into the habit of joining the Aitkens and a few others for those morning sits before heading out to the boatyard where he worked.

“Bob and I got along well, but he was twenty years older, and his formative experiences were quite different from mine. He’d been a prisoner in Kobi during the war, seeing Japanese families with their belongings on their backs escaping from the bombing and the destruction of everything in their lives left a lasting impact on him. His pacifism was very deep, very serious. He counselled people who were resisting the draft during the late sixties. There was a close connection with the Quaker community in Honolulu. One of the main reasons the Aitkens bought this old farm building that became the first Maui Zendo was because of his sympathy for the many young people kind of – what do you want to say? – drifting, seeking, looking for something. So, for Bob, the move to Maui was partly to set up a kind of environment, a kind of community, a kind of support for people who were seeking, who were open. And one of the things many of them were interested in – or at least had heard about – was this meditation practice, this Zen.”

There were two branches of the Zen group practicing now, an older one still associated with Koko-an in Honolulu and the newer Maui community.

“I had been involved in the planning for the move to Maui as a Board member of the official organization that was being set up to facilitate the legal aspects. Making use of a book put out many years earlier on how to grow vegetables in Hawaii, I drew up a planting plan that was used on a portion of the new property. I made a suggested daily schedule of activities. For some reason, at the time, I thought it was important to have the wakeup bell while it was still dark at all seasons. I collected information on various ‘craft’ projects that might be produced by residents for income. And when the Aitkens moved there in the fall of 1969, I purchased land a few miles away and began to build a home.”

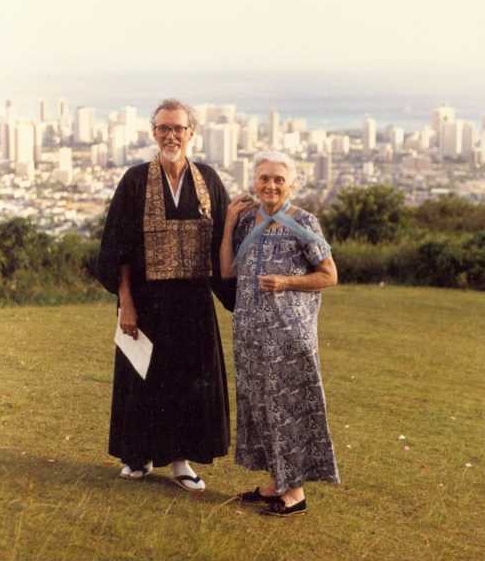

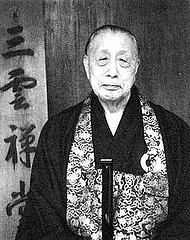

He continued to work in Oahu, however, and travelled back and forth, so he was not present for all of the changes that took place once the Maui Center was established. Chief among these was that Aitken – who had seen as a “elder brother” in the practice until this point – was given authorization to teach by Koun Yamada in 1974.

“Part of the intention in moving to Maui was to provide a supportive residential setting for these young people who were searching for something. Eventually the Maui Zendo developed a reputation for being a particularly – and I will use a word they might use – ‘spiritual’ place. I met all kinds because in those days on Maui you gave people rides when you could. So I’d be giving people rides, and they would tell me stories about how they came there. Sometimes they would have heard of the Maui Zendo and want a ride there. And then they would often ask what my ‘sign’ was. And I’d make up a sign, and they’d say, ‘Of course, I would have known you’d be such-and-such.’ You know? And then they’d explain why you’d demonstrated all these characteristics associated with that sign.

“Then that period began to die down, and there weren’t so many people that were coming and going on the road. Between 1972 and 1977 my contacts with the goings on at the Maui Zendo were episodic. I might get a call from Roshi or his wife, Anne, to help with some practical matters. But I was often on the Big Island or in Honolulu doing boat designing or building.

“The next major change came when there was an opportunity to buy a large house on a hill about one mile from the original Maui Center. It was rumored to have been a brothel during World War II. There was a large room that would serve well as a zendo, a number of small rooms in a row for residents, and a large kitchen. There was a large, covered porch. Parts of the structure were unfinished. One wing still had dirt floors in the rooms. Roshi asked me, because of my building experience, if I would do a survey and see if it was structurally sound or if they would be buying major problems. So, I did, and the purchase was made. That building then became the Maui Zendo and the older one became the Aitkens’ home.

“There were many jobs to do on the new Zendo and there were many sangha members who came to help as we poured concrete over the dirt to make solid floors, put a new roof over the large porch, replaced much of the water piping, replaced some rotten structural framing. There were always people in residence, but quite a few of the members now were at an age when marriage, or education for a career, or starting a career were beginning to affect the time that they could devote to sangha matters. Some had set up their own households and came for practice and workdays but were no longer in residence when a lot of maintenance had to get done.

“Meanwhile, the Honolulu sitters at Koko-an had grown and solidified around a group of dedicated students. When Aitken Roshi began to lead sesshin he would, in addition to holding them in Maui, go to Honolulu and provide practice opportunities there. There was a multi-year transition period where the group in Honolulu was becoming more active. People would come there to practice including some that may have begun on Maui but moved to Honolulu for educational or work opportunities. Roshi would go back and forth to lead events in Honolulu and lead events in Maui. He and Anne were still going to Japan regularly to continue practice with Yamada Roshi.”

The Aitkens eventually moved back to Honolulu, but they were also getting older. “Koko-an was being used as the practice center. It was still their home though for many years they had been donating a percentage of the property to the Diamond Sangha. But the overall layout made it less suitable for an older couple to share with an ongoing residential practice program.”

The Aitkens eventually rented a house “– that was just around the corner from Koko-an. Roshi could walk over for zazen. It was less than half a block. That seemed ideal. They were there for a while, and then that owner decided there was enough room – if he dug out from under the building, in the crawl space – that he could fit in another whole rental unit. Some of these old houses were built up on posts kind of high. So they came in with their excavating equipment and started digging. The house where the Aitkens were living kept changing shape. Anne might, one morning, go into the kitchen to open a cupboard door, and it wouldn’t open anymore because the house was settling. And the next day she’d go to shut the front door, and the door wouldn’t stay closed. At the same time, dust was coming up, and Roshi had had asthma and lung trouble of one kind or another since he was young. It became a terrible place for them to live.

“Eventually, a group of us said, ‘Look, this is wrong.’ Anne was seven years older than Roshi, so by now she is in her mid 70’s. We said, ‘This is just not right. Let’s find another place we can purchase so there will be no more moving around.’ I suggested, and others agreed, we look for a piece of property, and we’ll just build something. That way we can build something that had always been a dream of Roshi’s from an earlier time of having a place where he and Anne could live and other people, including families, could come and live too. He had this image from somewhere. I knew what he meant because in New England – where I grew up – there were these summer campgrounds, often religiously associated. They’d have a little church, and then they’d have cabins spread around. And church members would come, and they’d live in the cabins for the whole summer or part of the summer. An arrangement like that for Zen practitioners.”

Don found the appropriate location by accident. He was driving around the area “and I found a realtor sign that had fallen in the weeds. It was a 13 acre parcel a group of investors had tried and failed to develop for multiple houses. It was one valley over from Manoa, Palolo Valley. The investors had been blocked in their building plans because the water pressure in the nearest hydrant was too low for the fire department to be able to provide protection. If they built a reservoir for a million or more gallons on the property, then the fire department would sign off on their plans, but that requirement made the project uneconomical. I went to the fire department and asked, ‘If I put in an approved sprinkler system will that satisfy you folks?’ They said, ‘Yeah, sure. A sprinkler system’s fine.’ So, we bought the property.

“There were a few other hoops to jump through on zoning and some things with the water department, but we settled all that, and over a period of six years built the Palolo Zen Center, which is still the home of the Honolulu Diamond Sangha.”

Anne died in 1994, and Bob retired a year later. With Don’s help, he located a property near his son’s house on Kaimu Bay.

“His son, Tom, was a public-school teacher, and his mother, Roshi’s first wife, who was bed-ridden, lived with him. Then Tom decided to move back to Honolulu. Roshi at this point had an attendant to help manage things, but he had had some health challenges in recent years. Though a group of us would drive out to sit on Sunday morning, being there in Kaimu he was sort of isolated for most of the week. When he decided to sell and move back to Honolulu a sequence of events occurred. He slipped and had a fall. He probably had had a small stroke, as it turned out, and at that point he was in a wheelchair.”

Aitken had to move into assisted living for a while

“The place he stayed when he went back to Honolulu was a very nice location with different levels of assisted living. But there were problems that may have been related to his recurrent lung infections. I really don’t know any details. I was in Hilo and got irregular reports. But I felt, as did others, why isn’t there a way that he can live back in the residence we’d built for him and Anne at Palolo? Participating in practice, surrounded by friends and Zen students. Eventually things were worked out and with three Tongan woman as aides to help him with his daily activities he was able to remain there except for some hospitalizations due to lung infections, the last of which ended his life.”

Robert Aitken died in 2010.

Don is still active with the Diamond Sangha. He is a member of the Diamond Sangha Teachers Circle and a practice guide with the Hilo Zen Circle.

I remember going the (a) Maui Zendo of the Diamond Sangha in Haiku Hi just up the road from The Banana Patch and the road to Makawo.

they would open on Wednesday night and we would walk up for a hot soak, some dinner and meditation instruction.

LikeLike