Honolulu Diamond Sangha –

“I was one of those people who in adolescence started looking for truth,” Kathy Ratliffe tells me. “Read Be Here Now.”

Be Here Now had been written by Baba Ram Dass – formerly Richard Alpert – who, along with Timothy Leary, had pioneered the use of psychedelics as a means to attain spiritual awakening and had been fired from Harvard for doing so. The primary section of the book consisted of a series of complexly illustrated pages describing the process of spiritual transformation. A friend and I developed our own posters of those pages for a public presentation when I was in college.

“Yeah,” Kathy continues. “It opened my eyes to the fact that there was possibly something there somewhere that I needed to know or find out about or discover.” She attended Oberlin College where she studied Religion. “They made us study all the religions, Western religions as well as Eastern religions. I minored in East Asian Studies and got to study Japanese language and history and Chinese language and history, which was great. But then I realized when I graduated that I didn’t want to teach religion, I wanted to figure out what it meant. So, I kept looking.”

She also took up aikido and was teaching it by the time she graduated. A friend taught aikido in Rochester, New York, and after graduation Kathy moved there to continue her practice.

In Rochester she met Mrs. March. “I never knew her first name. She ran the Rochester Folk Art Guild and was the leader of this group that was based on the ideas of Gurdjieff.”

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff was an Armenian spiritual teacher who had died in 1949, but whose work became popular again in the 1960s.

“Mrs. March was very kind, and I went down there and explored it for a while. And basically what she said was, ‘If you believe what we tell you, you can join our community.’ And I said, ‘No, thank you. I’m not interested in anything that anybody can tell me. I need to find out for myself.’”

The friend she had been staying with in Rochester attended an orientation session at Philip Kapleau’s Zen Center. “So I went to an orientation there, and they literally said, ‘Don’t believe anything that we have to tell you. Here’s a way for you to find out for yourself.’”

She arrived as Kapleau was preparing to leave Rochester and retire in Santa Fe.

“He made Toni Packer the new teacher there, and all of the new students – of which I was one – went to Toni instead of to Kapleau for teaching. So I started practicing with Toni and doing sesshin with her. And I thought she was great. I was working on koans with her, but then she decided that she didn’t really want to work on koans anymore, or in the same way. She didn’t want to teach in a Buddhist context. So she moved out of the Zen Center, and there really wasn’t a teacher at that point so I went with her. She started teaching out of a Girl Scout camp, and we were holding retreats there. And I got more and more uncomfortable with working with her because she wasn’t using koans in the way that I was used to.”

Her personal circumstances were also changing. “My husband and I decided that I needed to develop a profession and work on my career, work on who I wanted to be. And neither of us were comfortable working with Toni in the way that she was working. We both loved Toni as a person, but . . . So we decided to wend our way to Hawaii and see what Aitken Roshi had to offer.”

That seemed a pretty big jump, so I ask if we could back up and fill in some gaps.

“First of all,” I say, “What was Philip Kapleau like?”

“I didn’t know him well.”

“But you had some sense of him.”

“Yeah. He was kind of a curmudgeon. I went to dokusan with him once, and he asked me what my practice was, and I told him, and he said, [in gruff tone] ‘Who gave you that?’”

“And you said you and your husband loved Toni.”

“We did. She was very sweet. She was supportive and kind and really present. She was an excellent first teacher for me.”

Kathy began her koan work with Toni.

“And it was because she changed her approach to koans that you became uncomfortable?” I ask. “Can you explain what the change was?”

She pauses for a while. It is a characteristic I had noted with teachers who continued in Toni’s wake, to consider a question carefully before responding.

“My sense was she was more interested in how people applied insights to their lives rather than through a more traditional Zen perspective which is seeing clearly into the point and being able to express that. So I just . . . I wasn’t sure that I’d really gotten the point. And I was quite young, afraid to ask questions, so I just accepted whatever she told me without questioning her about it. That was uncomfortable.”

“Then you said you and your husband decided you needed to develop a profession.”

“Right. My husband’s a nurse, and I thought, ‘I need to find something to do.’ I had been working in a tofu shop with some members of the Rochester sangha. I loved working there, but I decided it was time for me to look at what I really wanted to do. I decided to become a physical therapist.”

They had read Robert Aitken’s book, Taking the Path of Zen, and were aware of his sangha in Hawaii, so she chose a college that would bring them closer to him. She was accepted at Stanford.

I ask if they’d thought about the San Francisco Zen Center, which would have been less than an hour away.

“San Francisco is in the Soto tradition, so we weren’t tempted. We did visit there when we were living in Palo Alto, but we wanted to do koan training. And Robert Aitken was in the same lineage as Kapleau, so we thought, ‘Okay. That’s a decent fit.’”

I ask what Robert Aitken was like. She chuckles softly but doesn’t say anything. I mention I’d been told that he could also be a bit curmudgeonly from time to time.

“He wasn’t as much a curmudgeon as he was a bit socially awkward. He was very kind and sweet. But he was a little bit . . . He tried really hard to control showing what he felt in meetings and things, but he was always making facial expressions about how he felt about what was being discussed, and we would all kind of chuckle. But he tried very hard not to influence us as a group, but he couldn’t help it.”

“Michael Kieran said almost the same thing, that Aitken Roshi was committed to collaborative decision making, he just wasn’t very good at it.”

“Yes! Exactly.”

She has fond memories of him. “One time I was hospitalized for an acute illness, and Roshi and his wife Anne came to visit me in the hospital. He used to give us books to read, Zen books, when he was finished with them. He was a generous man. He and Anne threw a baby shower for me when I was pregnant. We were still living hand to mouth at that time, and they generously gave us a car seat for the baby. It meant a lot to us. He cared a lot about sangha members and relied on his wife to know how to express that.”

I ask how similar Aitken’s Diamond Center was to Rochester prior to when Toni Packer disrupted things.

“It was quite different. It surprised us how different it was. There were structural differences. In Rochester we had 35-minute rounds, and at the Diamond Sangha there were 25-minute rounds. And so, of course, we thought, ‘Oh, these people must not be as serious!’ Then we realized there’s just as much zazen, just timed differently. Of course, we were practicing at Koko An then, which was a house in Manoa – a three-bedroom house – and we were sitting in the living room/dining room area, and you could only fit twenty people max. So it was a smaller sangha. And when we had sesshin, we had only two bathrooms in the house. So the women all shared one bathroom in the early morning, and we would all just lineup in front of the toilet, waiting for our turn. Line up in front of the sink, waiting for our turn. That’s just the way it was. The men all shared the downstairs bathroom. So – you know – it was very intimate. And there were only three bedrooms in the house, so we laid futons all next to each other. A lot of the guys slept in the zendo. So, yeah, it was very intimate and intense in that way. And there was a little cottage outside where Roshi and Anne stayed, and that’s where the dokusan room was.”

“Those are physical differences,” I point out. “Was the atmosphere or teaching environment different?”

“Well, Roshi Aitken was a different person than Kapleau, and in Rochester at that time – I think it’s changed a lot now – the kyosaku was used without you asking for it, whereas at Koko An, you always had to ask for it. There was a lot more emphasis on kensho and recognizing people who had had kensho in Rochester. There was a ceremony they went through only after they’d finished all of the Miscellaneous Koans, and then they received a rakusu. So anybody wearing a rakusu, you know they’d finished the Miscellaneous Koans.”

One difference I’d been aware of was that Kapleau discouraged political activity. He wanted his students to focus on their practice rather than on social issues, whereas Robert Aitken was very socially involved.

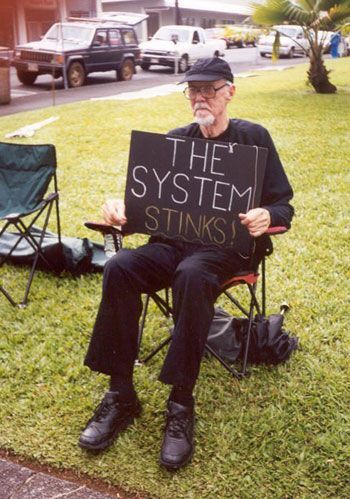

“He was,” Kathy says. “But he divorced it from his teaching. He invited us to do sit-ins with him and whatever, but he didn’t judge us either way, whether we went or not, and he always went. So he was out there sitting with his sign on the side of the road even with his wheelchair to the end. ‘The system stinks,’ and I was there next to him.”

“You joined him?”

“I did. I joined him a number of times. Protesting against the Iraq War, just standing on the side of the road with signs. It was an interesting experience. He put himself out there. ‘This is what I believe.’ And – you know – he didn’t pay taxes for a long time because he refused to allow his money to support the military. He put the money into a special account, and I think he later had to pay it all. But he had strong convictions.”

“What was it that attracted you to all of this?” I ask. “You moved all the way from New England across the continent to Hawaii. What were you getting from it? What was it doing for you?”

“I just needed to know. From the time I was a teenager, I just knew there was something that I wasn’t seeing.”

“And Zen helped you address that issue?”

“It has. Yes.”

“How?”

Once again she reflects for a while before answering. “It’s my way of pursuing, trying to figure out for myself what life is about.”

“So a way to address certain questions you had, but how did it do that?”

“It was a way of looking at this, my life – what this is – in a different way through doing zazen that I couldn’t do any other way. I could see more clearly. Zazen helped me see more clearly.”

The Diamond Sangha is a lay group – “We don’t do ordination” – and she is currently a “Dharma Guide.” “It’s the equivalent of what other groups call an apprentice teacher.”

I ask how that came about.

“Well, I just kept practicing,” she says with a chuckle. “I practiced with Aitken Roshi when he was alive from about 1985 ’til he retired in 1996. And then Nelson Foster became our teacher, but he only came about three times a year because he was based in California. Then after about ten years, he invited Michael Kieran to be teacher, so I switched over to Michael. He’s my fourth teacher now. I’ve been working with Michael since 2005, and he invited me to be a Dharma Guide.”

“How is Michael different from the other three? What makes him unique?”

There is another long, reflective pause. “The practice is pretty similar in the dokusan room. Michael is carrying this lineage with integrity and vigor. Nothing has been lost; there’s no watering down of the practice. Like Aitken Roshi and Nelson, Michael is fully committed to this teaching and to the Way. He is particular and exacting. I trust him. And he has gotten very involved in the sangha, looking at how everything we do supports our practice. In one example, he’s helped us develop a strong work practice – samu – in keeping up the place, making sure the place is clean and that the toilets are cleaned and the lawn is mowed. And it takes quite a lot of work. We have a large facility. And not only did it need to be done, but it is good practice. And it has worked very well. Not only has it helped our facility become a better physical place, it has helped our sangha come together and our practice come together. So that’s an emphasis that he has made. Not that the others didn’t do it, but Michael’s done it with some focus.”

The sangha members range in age from early 20s to those in their 70s.

“The aging hippies,” I suggest with a laugh.

“Yeah. But we really do span the range, and we are getting more younger folks. We have an orientation to practice that we offer once a month. During COVID we actually had to offer it twice a month because we had many, many more people interested in learning how to sit. But of the ten people who come to an orientation, maybe one will come back once or twice. And out of those, one of those will come back once or twice. Maybe one will come back and sit with us for a while. And out of those, only one will become a long-term member of the sangha. Only one percent.”

“It’s like that about everywhere,” I point out. “And I suspect it’s at least in part because they get what they want at that first orientation. They’re shown how to meditate, and that’s what they wanted. They don’t think they need to join a group to do that.”

“I think that’s right, and we emphasize Buddha, Dharma, Sangha in our orientations. I think the main reason people don’t come back is that practicing entails a lifestyle change. A change in your life. You’ve got to commit yourself to come at least once a week to sit with the group. And you’ve got to do longer-term sittings. You’ve got to do a zazenkai or sesshin to really practice. And it is a rare person who’s interested in changing their life to do that.”

I ask what she believes people look to her for now that she’s a Dharma Guide.

“Well, there’s a range, depending on where people are in their practice. Those who are working on advanced koans just want support working on their koan. Those who are new to the practice are looking for guidance. Guidance in their practice and also in their lives. Which aren’t that different. How do I deal with not knowing what to do in my life next? Or how do I deal with interpersonal difficulties? What do I do with all these emotions I’m feeling? They also are looking for guidance in how to practice. How do I stop getting carried away by these thoughts?”

“So they might come to you for the type of things somebody else might turn to a therapist for?”

“Right. The difference is that I try to provide a Dharma perspective to support them rather than a psychological perspective. The purpose of psychology is different than that of Zen practice.”

“And you? What is it that you hope for the people who work with you?”

“I hope that people will gain more insight into their own lives and be able to deal with the ups and downs of their lives. You know, I overheard Kapleau telling a story once in a gathering. It happened after Toni decided to leave, and he had come back. And there was a gathering. I think it was at the Ox Cart, Rafe Martin’s bookstore. I was standing next to Kapleau, and somebody asked, ‘How do you weather these difficulties? I mean, this is major what happened.’ And he said, ‘You just keep facing into the waves. Just like a boat. If you face into the waves, you can cut through the waves and not have quite as rough a time. If you go broad beam to the waves, you’re going to get tossed over.’ It really impressed me. I thought, ‘Oh, that’s an appropriate metaphor.’ So I hope people will learn skills to keep facing into the waves because life is going to continue to throw us waves. And if you let yourself be thrown by your emotions and all your thoughts and all the other things that assail you about change, it’s going to be very difficult for you. Whereas if you just face what’s there, that’s what is needed.”

“Has there been a continuation of Aitken Roshi’s political activism in the Sangha? Are there remnants of that legacy?”

“There is not. Although I think people feel very strongly politically individually. We are trying to address how people can include everyone and not get so one-sided in this divided world. Michael, I, and others are very interested in looking at Hawaiian culture, what we can learn from them. We have what we call a Dharma Studies series every year –the Robert Baker Aitken Roshi Memorial Dharma Study Series – it’s funded by royalties from Roshi’s books. And for the last couple of years we’ve invited native Hawaiian people who are very active in their culture and their community to share with us about the place where we are, Palolo Valley, and also about the Hawaiian culture. And it’s been fascinating.”

An implied question running through our conversation is to what degree Zen remains relevant for contemporary North Americans. As we come to the end, she tells me: “I think that people – especially people who are caught up in a lot of the online stuff today – need more grounding so they can see what’s important and what’s not important. And I think that Zen practice is a way to see through to who we are and how we can better operate in the world. By ‘better’ I mean how we can decrease anguish, sadness, our conflict with how we think things should be and how they are.”

It’s as good a reason to maintain the tradition as any I can think of.

😊

LikeLike