Every Day Zen Sangha –

Susan Moon begins our conversation by telling me she came to California from Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the 1960s, as “a kind of wandering hippie with my then husband.

“My parents were WASP agnostics,” she says. “God was never mentioned in the house. That worried me as a child, and I thought, ‘What if there is a God? I better check it out! He might be mad at me if I don’t believe in him.’ But they were very progressive, and I am very grateful for the values I got from them. And then they and I became interested in the Friends, the Cambridge Friends Meeting. My grandmother was a Quaker, and she was my first spiritual teacher. She was a very spiritual person, interested in Zen, and she taught me about Zen even as a child and told me about it and the adventures she’d had when she visited Zen monasteries in Japan herself. So I was always a bit of a seeker independently of my parents who didn’t have much interest in that. They weren’t upset, I guess, when I went to the Episcopal Church as a teenager and joined the teenage group. But then that lasted only a couple of weeks because I thought it was very unspiritual. So it was when I was living in Berkeley already . . .”

I hold up my hand and interrupt her, “Let’s take a step back. What took you to Berkeley?”

“Well, my husband was a writer. He’s a very smart Harvard dropout visionary type, and very active with the Civil Rights movement and a radical person. And he wanted to go to Texas – Corpus Cristi, Texas, where he’d gone as a child with his grandparents – to finish a novel he was working on. And we went there with our baby and lived in a sort of motel cottage on the beach in Corpus Cristi, Texas, which in winter there’s nobody there. We were sort of the only occupants. It was terrible! Weird and lonely. Then he had a couple of psychotic breakdowns as a result of who-knows-what, combination of drugs and kind of crazy mother. Whatever. And I was there with him in Corpus Cristi, Texas. And he was completely paranoid, and I didn’t know what to do. So I called our good friend, Adam Hochschild, who became the founder of Mother Jones Magazine later and is a wonderful writer, and I said, ‘Help! What can I do?’ And he said, ‘Come out here, and I’ll help you.’ And we came and landed in Berkeley, and he got us appointments with a psychiatrist, and we stayed with him, and he was just incredibly kind and helped us, and then we ended up staying in Berkeley and separating and divorcing a few years later.”

It was 1969 when they arrived in Berkeley, the period when a lot of young people were making their way not only to California in general but to the San Francisco area in particular, many of them paying at a visit to the San Francisco Zen Center along the way. Zen was literally in the air in Berkeley, with Alan Watts’ talks on KPFA radio. Susan remembers hearing him in 1973, and then a friend told her, “‘Oh, there’s this incredibly hip place in the mountains. It’s so hip, and there are these people there who are being Buddhist monks in this remote valley, and they make the most amazing bread! And you can go visit there.’

“So I went there as a guest one weekend in the early days of Tassajara when it was kind of informal, and I just loved it. And this was right after my husband and I split up, and I thought, ‘Gosh, if I was not a single-mother, I would come here and be a monk.’ And then somebody said, ‘Well, if you like this here, there’s a Zen Center in Berkeley.’ Which I didn’t know. So then I came home and started going to the Berkeley Zen Center.”

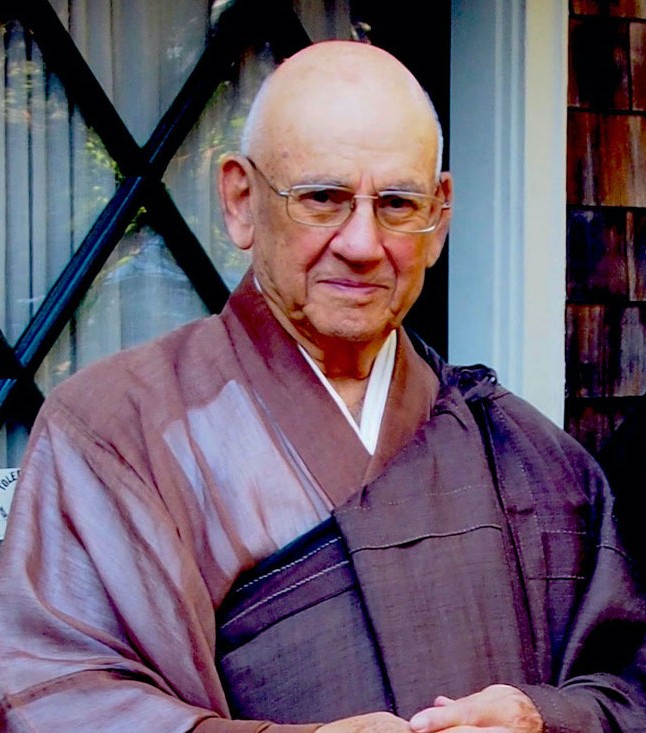

The resident teacher at Berkely was Mel Weitsman. I tell Susan that Mel was one of the three people who took part in the very first interview I conducted in this series.

“Wow! Well, he was great. He was like my grandpa or something.”

I ask her to tell me about him.

“Well, he was very . . . stolid and kind of practical in a way. And he wasn’t really what I expected a Zen teacher to be. He was sort of disappointing to me at the beginning because he wasn’t wild and poetic and flamboyant in any way, and he didn’t seem like he was going inspire me to have a great awakening. But my respect for him grew a lot over the years, and I’m very, very grateful to him for his ‘thereness,’ his ability to be completely present and supportive and really selfless. He was really so unnarcissistic. His lack of charisma was a very generous thing in a way. He wasn’t trying to be something to everybody or be a star or anything.

“But I also continued to want a little more intellectual stimulation or a certain kind of understanding of my own deep existential suffering and longing which was so intense. I was always having this terrible longing that was not satisfied. And I always felt, ‘What . . . what . . . what is it? I can’t get it. I’m never going to get it. What is it?’ And I felt like he didn’t get that, although he probably did get it much more than I give him credit for. Whatever I said, he would always just say, ‘Well, just sit zazen and it will drift away.’ And that isn’t what would happen. I would sit down in sesshin, and my mind tortures would get all the more intense. It was sort of like the perfect opportunity for these different tracks dug in my brain. I’d talk to myself about how I couldn’t get it. How it was so hard, and how did everybody else get what was the meaning of life, and I didn’t? Anyway, it got worse, and I would just have to flee from the zendo, go out for a walk or something which led me to study with other teachers as well, that longing.”

I ask who the other teachers were.

“Joko Beck was very helpful to me. She used to come up to Berkeley and do retreats which I would go to, and I went down to Pacifica a few times to do retreats with her. I also really loved Maurine Stuart, but she was far away in Cambridge. She came to San Francisco Zen Center and Green Gulch a couple of times, and I sat with her there. She was really wonderful. And also Robert Aitken I loved, and he came to Berkeley sometimes to talk, and also – but that was sort of later – the Buddhist Peace Fellowship was very important to me, and that connected me with Robert Aitken. He was a really helpful teacher. And then there were two more that would be worth mentioning, Reb Anderson at San Francisco Zen Center.” Reb was Richard Baker’s successor as abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center. When co-abbots were introduced and term limits imposed on abbots, Reb served as co-abbot with Mel.

“I had wanted to go to Tassajara ever since that first time long ago. I vowed to go to Tassajara and do a practice period there before I was fifty. So when I was 49, I went to Tassajara, and I did a practice period led by Reb Anderson. And I hadn’t practised with him before, and Mel and Reb were kind of alternating leading practice periods at that time, and I chose one that Reb was leading on purpose because I wanted to connect with a different teacher. And we had a good connection, and I felt Reb did see this kind of angst and existential crisis, and he responded to it. And he was almost like the opposite of Mel in various ways. He was very charismatic, and I think there was some trouble with that. So he was my teacher, my main teacher for a while. I went to Green Gulch to be in a group with him, and he helped me, and he was generous. And I was shuso[1] with him at Green Gulch for a practice period in 1996, but I also had some trouble with the adulation that his students had for him, and the sort of feeling that you had to ask him if you were going to change the type of toothpaste you were going to use. He said that one time. He said, ‘Well, if you’re practicing with me, you should talk to me before you change your kind of toothpaste you use.’ I mean, he was joking about it, but I didn’t like that way of being. And all this time, I continued to live in Berkeley and go to Berkeley Zen Center. And I would go every Saturday to the talk, and I would continue to be with Mel and really appreciated the sangha in Berkeley, and Mel, and his steadiness, and his teaching. That never changed.

“And I knew Norman Fischer.” Fischer was Mel’s heir and served as co-abbot of SFZC3 with Mel when Reb’s term came to an end. “I knew Norman as a friend because I knew people in the poetry scene. My brother-in-law, Bob Perelman – who is not at all a Buddhist – is a close friend of Norman’s and part of that poetry crowd. I had a little publishing thing years ago called Open Books, and I published books about the Peace Movement, and I published Norman’s first book of poetry, which nobody knows about anymore, which was a little small-press thing called, Like a Walk Through a Park. So I knew Norman as a friend and as a poet, and then there he was at Green Gulch teaching, and he was a wonderful teacher, and I thought, ‘Well, maybe Norman could be my teacher.’ And then I thought, ‘No! No! He couldn’t be my teacher. He’s my friend.’”

She talked about her quandary to some Zen people who assured it wasn’t a problem. “So, anyway, Norman became my teacher as well as my friend. And then, about a year later, he left Green Gulch and started Every Day Zen. So I was part of Every Day Zen from the beginning in 2000. So now Every Day Zen and Berkeley Zen Center are both my main sanghas. Berkeley Zen Center is sort of the place in a way. I’m just so grateful that it’s there. That’s made a huge difference in my life, and it’s a wonderful sangha. And I worked with Alan Senauke for many years at the Buddhist Peace Fellowship when he was Executive Director and I was editing the magazine there. So I feel like that’s my family, and it’s there, and I can go to this place, and there’s something happening there. And Every Day Zen isn’t a place. We rent a room in a church to have our meetings, but it is a sangha. It’s a wonderful sangha, and Norman is great, and it’s really enlivened my practice a lot and helped me a lot and most of the teaching I do is in Every Day Zen Sangha. Not all, but a lot.”

Although Aitken and some of the other people she studied were koan teachers, Susan tells me that she did not take up koan practice. “I did a little bit of Mu with Joko and Aitken Roshi, but I don’t think I scratched the surface. I didn’t feel like I was really doing much.”

“Sometimes it’s that sense of angst and not necessarily knowing what that angst is based in that drives people to koan practice,” I note.

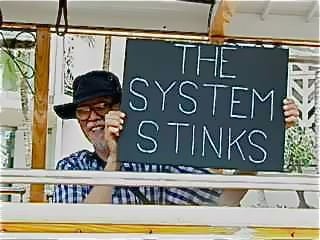

“You could be right,” she says, laughing. “I could have missed my true calling because I didn’t stay with any of them as a very long-term discipline. They influenced me a lot and encouraged me a lot. Well Maurine was too far away, but I just loved her, though, I think, as a woman. That was another important thing for me to see, because in the early days there were few women teachers. And then both Joko and Maurine were very encouraging to me as a woman practitioner. And Robert Aitken was very encouraging to me as a person concerned about social justice and political activism. When I first started sitting at Berkeley there was a kind of a divide. It was the ’70s, and Mel had a very strong belief that we shouldn’t say anything political, because he wanted everybody to feel free to come there. Which I think is a very reasonable point of view now, but, at the time, I was outraged. And I was the editor of the Berkeley Zen Center newsletter for a couple of years, which came out once a month or something, and I had a kind of a battle with Mel when I tried to put in an announcement about a meeting of a group of Buddhists who wanted to come together to meet about blockading Livermore Weapons Lab or something. This separation was a painful thing for me because I had activist friends – I was an activist before I was a Buddhist – and they kind of had the feeling, ‘Why do you want to be a Buddhist? Those people just want to contemplate their navels and think about themselves all the time.’ And the Buddhists thought, ‘Why do you want to be an activist? Those people are just angry all the time; they’re lost in their anger.’ Of course, I’m totally exaggerating about what those people thought, and neither was true probably. But I felt this divide, and I was so, so grateful when the Buddhist Peace Fellowship – thanks basically to Robert Aitken and others – formed, and then those two worlds came together. And then better yet, I got a job working there, editing this magazine, so my Buddhism, my activism, and my love of writing and words and editing all came together in one job, which was very perfect for me.”

“You said Mel didn’t want people talking about political issues because he wanted everyone to feel free to attend there. What was the Berkeley community like in the early days?”

“Young, for one thing. We were a lot younger. In fact, young people are coming to the Berkeley sangha again, but at one time, nobody new seemed to be coming; we just kept getting old. Anyway, everything felt sort of homemade, and we were always having bake sales for this or that. Going up to the Sonoma Mountain Zen Center – Bill Kwong’s place – for the grape harvest, ’cause when they first bought that land it was a muscatel grape vineyard, and they continued to harvest the grapes for a few years.” Bill Kwong was another teacher associated with the San Francisco Zen Center. “So all comers were welcome to go to the grape harvest. We did sort of funky weird things like that. And the people in Berkeley were kind of Berkeley types, sort of a raggedy bunch or something. Auto mechanics and gardeners, seamstresses. And people just very enthusiastic about sitting down and staying still.”

Another teacher was Ed Brown, who was the author of very successful Tassajara Bread Book. Susan remembers a talk he gave at Tassajara about Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. “‘Buddha taught that life is suffering. And Suzuki Roshi taught that too, and we’re suffering all the time. Even when we don’t know it, we’re suffering. Even when we think we’re having a good time we’re suffering.’ And then everybody burst out laughing. I liked that paradoxical viewpoint. And later when I wrote my first book, The Life and Letters of Tofu Roshi, it’s about an imaginary Zen master named Tofu Roshi – who was slightly modeled on Mel – and Tofu Roshi’s teaching was that even when we’re suffering, we’re actually having a good time

“But people at Berkeley Zen Center, there was a lot of sweeping and gardening and baking. And sometimes we would have classes. And Mel taught us about taking care of what’s in front of you, about the chop-wood/carry-water aspect of Zen practice. And we would clean the zendo and the community room on Monday mornings, and sometimes I got the job of washing the leaves of the big rubber plant with a solution of water and milk with a sponge. I mean who would think that was part of Zen practice! Or waxing the floor.”

She didn’t attend the San Francisco Zen Center very often but her impression was that it was “more dour,” which causes us both to laugh. “Everybody was in black. It was after Suzuki Roshi had died. So when I first was going there it was Baker Roshi’s territory, and people were wearing all their robes and everything all the time. And people were famous for not being friendly. It was a very famous place for not being friendly. You would knock on the door, and somebody would stick their nose out and say, ‘What do you want?’ So I wasn’t drawn to City Center, but I was drawn to Green Gulch which was so beautiful and sort of still newish and to Tassajara, of course.”

As our conversation draws to a close, I ask her how she would describe her approach to Zen as a teacher.

“Well, I would say my practice and my offering as a teacher – insofar as I am a teacher, which is a different way of being a teacher – is really to be my authentic self, to sort of model the teaching that we’re already enlightened, and our job is just to know that and rediscover that. We’re already enlightened. That’s the thing that I need to remind myself, that I’ve been reminding myself and that I try to help others with and what that looks like. I help people see that, ‘You’re not the only person that thinks you don’t know how to sit zazen. You’re not the only person who can’t overcome your greed or self-clinging or whatever.’ So I reveal myself in my vulnerability not to get people’s attention or something. I’m just talking about how it is to be a human being. And I do this in my writing, and I know from the responses I get that one of the things people appreciate is that they see that I – who has some credibility as a long-term Zen practitioner – am also a person who might get up in the middle of the night and go raid the ice box and eat the rest of the ice cream with a spoon standing at the freezer. Or I might still be beset by longing at 3:00 in the morning and think, ‘Oh, no! What’s wrong with me?’ That might still happen to me. And . . . and I have faith nonetheless in the Dharma. The word ‘faith’ means something to me. I have faith in the Dharma, that it’s there for us.”

[1] “Head seat.” The head student in a practice activity.