Kanzeon Big Mind Zen

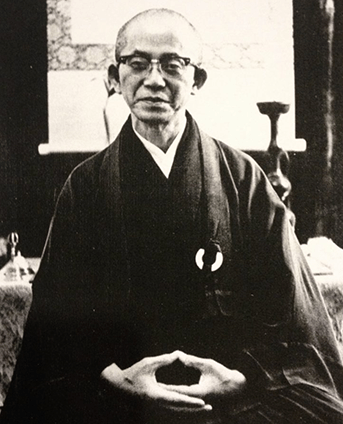

Dennis Genpo Merzel is the founder and abbot of the international Kanzeon Big Mind Sangha. He was the second person – after Bernie Glassman – to whom Taizan Maezumi gave Dharma transmission. Susan Myoyu Andersen was the tenth.

“Well, Genpo is complex,” she tells me. “But one thing that I will say about him, he always seemed to understand and care about my concerns and my issues. If I had a grievance at Zen Center, he would always listen. I called him a World Class Carer. He really cared about people. For all of his challenges and issues and problems – which are very real – he also really cares about people.”

I haven’t met Genpo in person. My conversation with him took place over Skype. But one gets the impression of a strong personality. He is witty and charming. I suspect he’s an easy person to like. He’s also a guy who was asked in an open letter signed by sixty-six teachers – affiliated “with all of the major schools of Zen in the west” – to no longer “represent” himself as a Zen teacher, although one of those who signed the letter admitted to me that if he were asked to do so now he would decline.

It’s complex.

“I first heard of Zen around 1969, from a man named Fred Ancheta, when I went to buy some marijuana and LSD,” Genpo tells me. He’s also a good storyteller. “I go to an unfamiliar house to pick up this stuff, and he opens the door, and I go, ‘Oh, my God! My old friend, Fred!’ We had gone to Junior High School and Junior College together. So we sat down and smoked a joint, and he sold me these hits of acid. On the way out, I notice two books lying on the floor. The Way of Zen by Alan Watts and Zen Buddhism by D. T. Suzuki. I asked him, ‘What’s Zen?’ Fred said, ‘Well, I’ve been studying Zen, and I think it’s where everything in the West is leading – Western Philosophy, Western spirituality, Western psychology, Western science – everything is leading towards Zen.’ And that was it. I left.

“Two years later, I’m out in the Mojave Desert. I was having a difficult time in a new relationship that had only been going on for about a year. And I had been divorced already. I was 26. I’d gotten divorced at 25, and I found the same pattern going on. I felt confined, restricted, and was having a difficult time, so I needed some space. So I told my partner, ‘I’m going to go to the desert, and I’m going to invite my friend, Kurt, and we’ll camp for a few days, and I’ll be back on Monday.’ So I invited my friend Kurt, and he brought along his new girlfriend, and the three of us went out to a place in the Red Rocks called Jawbone Canyon. They decided to hike off alone, and I decided to go to the top of the nearest mountain, and I climbed up the mountain.

“I sit down, and I ask myself two questions. The first question was how could I have screwed up my life so badly? I’m only 26 years old, and I’m already divorced. I’d had the expectation of being much more stable than that, living a long life with my first wife, and I’m already divorced. And I’m in a relationship with the same patterns. How could I do this to myself?

“The second question came up when I looked out and saw my VW camper where we were going to be for the next three days. I look out there, and I say, ‘Well that’s home.’ Then, ‘Wait a minute. That’s not home. Home is back in Long Beach where I live across the street from the ocean, on Ocean Boulevard.’

“Then something happened. Body and mind dropped off. I became one with the universe, one with the interconnectedness of all things, the oneness of the universe. I am that. In other words, God, Love, the Universe, the Whole. The universe opened up, and I realized not only am I always home, it’s unconditional. There is no other place but here, now, this. I’m always here/now, and it’s always home.

“It was profound. To this day it’s probably the most influential experience of my entire life. I’ve had bigger experiences, but not one that was so influential. It changed my life. Now, my friend Kurt had a PhD in Psychology from the University of California Santa Barbara, and he said, ‘You know, the way you were talking when we got reconnected that evening, you sound very Zen. I think you had a Zen experience. They call it a kensho.’

“Now, if he had said, as a psychologist, ‘You sound insane, you sound really screwed up, you need to go to a mental hospital,’ I would have had a very different life. He saved my life. And for that, I’m forever grateful. He changed my life by saying those words, ‘You had a Zen experience.’ Because he could have taken the perspective that my mother did. She said, ‘Dennis you have gone insane.’ ‘No mom,’ I said, ‘I have gone sane!’

“Kurt gave me a copy of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha when we got back, and I read it. It was very powerful for me, and I started to study about Buddhism, all kinds of Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Zen Buddhism and Hinduism. I began to study Carl Jung and Freud, Maslow and all the other great therapists and philosophers at that time. I studied, and I studied, and I studied all about this kind of transformation. I was trying to find out what happened to me – you know? – trying to grasp what happened.

“But I was most at home with Zen and the koans and the Zen Masters. And those were all Chinese. I didn’t study the Japanese, only a few like Dogen Zenji and Hakuin. It was all these Chinese. You know, Huang Po and the Sixth Patriarch, all of those great ones. But I’m not an avid reader. So I didn’t really read all of each book; I just read parts of them.

“I was teaching school, at the time. I gave notice and said in June, when the school year’s up, I’m taking my pension, and retiring. So in June, I hit the road in that VW camper. I went all over the northwest, up into Canada. I sold my camper in Montana, and I hiked up through Glacier National Park, fifty miles on my own over glaciers in Adidas tennis shoes no socks.

“I met two guys and hung out with them. I didn’t have any food. I just saw a sign, it said ‘Fifty miles to Waterton Canada,’ and I just took it. 26 years old, kind of young, dumb, and all that. I met these two men the first night, and I had a plastic bag of brown rice, and a little cooking pot with me. So I cooked this brown rice and offered to share it with them. It was all my food for a week. Then they shared their food, and they had plenty. So we became best buddies. Spent five more days together hiking. On the third day, I hiked up this mountain to where I could look down on fifty mountain peaks. It was extraordinary. On that peak I realized my destiny, I realized I was to be a Zen Master, that was my destiny. I believe that set the rest of my life in a certain direction. On the fourth night, we were visited by a grizzly. We covered our heads under our sleeping bags, and he eventually left. It was one scary moment. On the fifth day, we arrived at where they had a camper waiting, and we drove together around a few National Parks, Vancouver Island, down to Seattle, and then we split up.

“Then I spent a year in a mountain cabin owned by a man I met hitchhiking. He had a cabin five miles from town on a road that went into and through a great ranch called the Santa Margarita Ranch, one of the largest in Californian history. So after this journey, I come back and join him there. He invites me because he had been robbed three times. He was a musician, so he had guitars. He had a piano which, of course, wasn’t stolen, but he had these guitars, he had a sitar and other musical instruments, and some sleeping bags. They stole everything. Wiped him out. I said, ‘Listen. I don’t have a home. I’m a Zen person.’ A Zen monk, I called myself. ‘You let me stay here, and I’ll take care of it. I’ll look after the place for you. I’ll make sure nobody robs you.’ He said, ‘Deal!’ So I said, ‘How long?’ He said, ‘Indefinitely.’ But it became problematic ten months later in May when my former girlfriend joined me. He needed to have privacy when he came with his wife and his kids, and we were on the property, so he asked us to leave in June.

“So I was there from September to June. I believe that year alone in the mountain cabin really was the groundwork for the rest of my life. I spent it chopping wood and carrying water, alone with my own thoughts and mind which gave me an understanding of who I am. So at Christmas I decide to go spend some time with my mother. So I go down there, and in the meantime I buy an old jeep.

“So now I went down to San Luis Obispo occasionally for a few hours – you know – hanging out there. I put a sign up in the local health food store, and I invite people to come out and sit Zen with me. So in February, people started to come out and sit with me. We had a little circle, maybe twenty people, and I’m teaching them Zen. One of them happened to know yoga, so he taught us yoga. Another one was an astrologist, so he did all of our charts for us. So we had this little group of people hanging out, and once or twice a week they’d come out to my place, and I’d teach them how to sit and we’d read Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.

“One day an older gentleman, probably in his 70’s – a man named Earl Eddy – comes driving up in a black Cadillac. He’s wearing all black, and he brings out this black round cushion which I later learned was a zafu. He sets it down, and he brings out this bell, and these clappers, and he says, ‘Do you mind if I organize this a little bit?’ Because he looked out and saw twenty hippies sitting in a circle on bathmats and blankets and sleeping bags. He wants us sitting more formally.

“When it was over, he said, ‘Let’s talk.’ And I said, ‘Sure.’ And he says, ‘It’s time for you to meet a teacher. You need to meet a Zen Master. I’ve been studying with this young master named Maezumi Sensei, and he has a teacher, an older man, my age coming to visit and spending some time. His name is Koryu Osaka Roshi. And they’re going to be holding this sesshin’ – this was mid-March of ’72 – ‘they’re going to be holding this sesshin beginning the third week of March. If we get out to a place where I can make a phone call, I’ll call Maezumi Sensei and ask if you can attend this sesshin.

“It was very interesting because several days before Earl arrived at the cabin, I had a very powerful experience. I was sitting, and I realized that I needed to meet a true living Buddha, a Zen Master who embodied the lineage. I knew that I needed to be crushed, ground to dust, that my ego had become so big, so inflated, because I realized I am The Buddha. However, even though I felt I did not need any affirmation of this, it was important to be face-to-face with a living Buddha Patriarch.

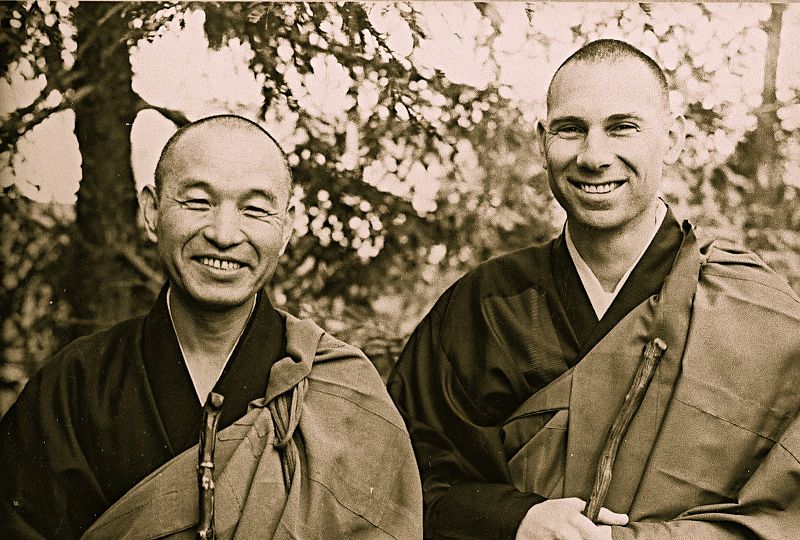

“So we go to a local store, phone Maezumi Roshi, and Maezumi Roshi says, ‘Bring him on.’ So that Wednesday, I hop a freight train and ride it down to Los Angeles. Then I come over to the Zen Center, and I meet Maezumi Roshi, I meet Koryu Roshi, I meet Bernie Glassman, I meet Bob Lee, I meet Sydney Musai Walter, Charlotte Joko Beck, so many future Zen Masters, I don’t know how many. All eventually became Zen Masters, but, at that time, there was only one, Koryu Roshi.

“At the end of that sesshin, Maezumi Roshi received Inka, final seal of approval, from Koryu Roshi. And from then he was also known as Roshi. I didn’t immediately have a warm feeling with him. But I felt love for Koryu Roshi. I came into interview with him, and he said to me, ‘I want you to count your breaths.’ I did that, and I came back a few days later. He said, ‘How is it going? Can you count to 10 without losing count?’ I told him, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘You’re ready for Mu.’ He asked me, ‘What is Mu?’

“I went out. I sat down. I came back in. I said, ‘I’m done with koan study. I know them all. It’s all me. It’s all my life. All the koans have the same answer. It’s me. Nothing else. Just this,’” Genjo says, patting his own chest. “He rings me out. And then I come back in, probably later that day, and I say, ‘Okay. What do you want me to do?’ He said, ‘I want you to do koan study.’ I said, ‘Okay. Where do I start?’ He says, ‘What is Mu?’ So that began that. Then Maezumi Roshi starts doing koans as dokusan after that. But that was my initial experience with Koryu Roshi.

“So I love Koryu Roshi. He’s so warm, so intimate. Available, open, receptive. And the most powerful human being I ever met. Enormous power. He had such energy and such equanimity and such power. And he was very personal. He really touched our hearts.

“With Maezumi . . . I was assigned to work with him. At that time I was doing a lot of bodybuilding, so I was able to bench press nearly 400 pounds. We’re moving boulders. He’s doing a rock garden, and I was assigned to move the boulders for him. So these heavy boulders, I’m lifting them up and putting them down, and he says, ‘Nah, nah, nah. Put it over there.’ I put it over there. ‘Oh, no, no! Move it back to where it was.’ This went on for days.

“But at some point we’re doing this rock garden, and he said, ‘Who’s your teacher?’ I say, ‘I don’t have a teacher.’ He says, ‘Well, what’s your Zen experience?’ ‘I’ve read D. T. Suzuki; I’ve read Alan Watts.’ He says, ‘Alan Watts! He’s not Zen. Okay,’ he says to me,” – Genpo speaks with a gruff Japanese accent – “‘What is Zen?!’ I took the spade that I had in my hand, and I shoved it down in the ground and said, ‘Just this! He said, ‘Your Zen eye is only partially open. You need deeper study.’ So, okay, I was a little hurt because I felt he didn’t see me. But I accepted it. And I said, ‘By the way I’m leaving this sesshin.’ He said, ‘Why are you leaving?’ I said, ‘This is not Zen.’ He said, ‘What are you talking about?’ I said, ‘This is full of rituals and bowing. Zen is not about bowing to idols! Who are we bowing to? Aren’t we bowing to ourselves, the Buddha?’ He said, ‘Wow! You are the most arrogant young man I have ever met.’ He said, ‘I want you to come and visit me after lunch.’ I said, ‘Okay. I’ll come. I’ll wait till then.’ Because I was going to leave right after the work period.

“So I sit the next three periods, whatever it was. I come up to him, and he starts questioning me. Who have I studied with, where did I study, what have I done? I said, ‘I live in the mountains five miles from any other human being, and I sit six/seven hours a day on this picnic table, because there’s rattlesnakes all over the place, and the only way I can get away from them is to sit on top of this table. And I said, ‘I just sit, and I chop wood, and I carry water.’ I had no electricity. I had no stove. I had an old Coleman, a little camping stove. And that’s how I survived. So I said, ‘I’m going back home.’ He said, ‘Well, at least spend the next four days with us and finish the sesshin.’ I say, ‘Okay. I can do that. I’ll complete it. I’m not a quitter.’ So I stayed, and that’s when I had the dokusan with Koryu Roshi and so on.

“Well, I went back to my cabin until June, and I had some correspondence with Maezumi Roshi. He wrote me a few times. And I apologized for my arrogance and for the way I talked to him.

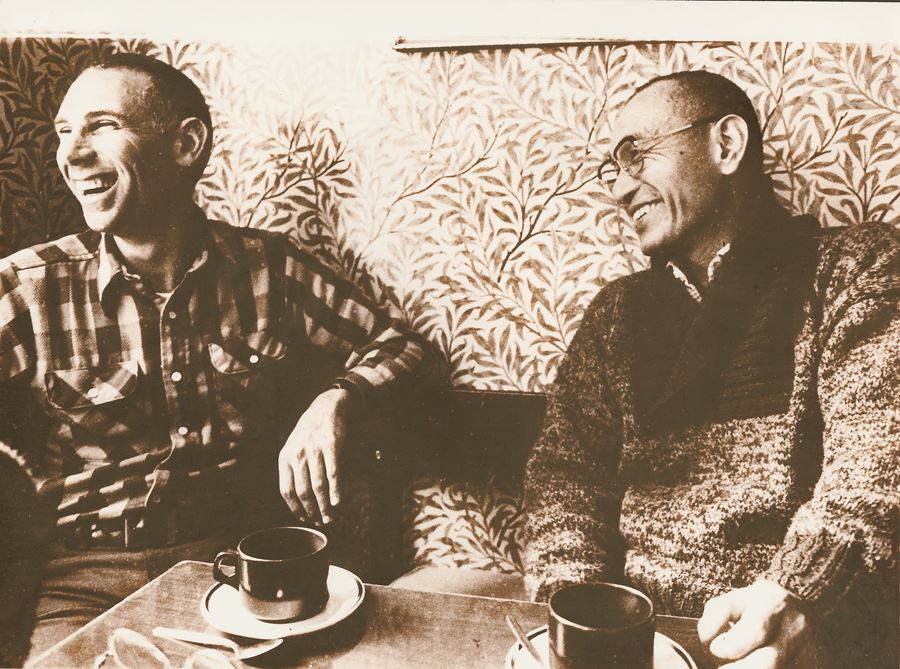

“So, when I went back down to Los Angeles several months later, Roshi allowed me to park my old van in the back yard. During that time, Roshi was having a hard time. He had been divorced from a woman who was a Buddhist nun. And his back was hurting him greatly, and he had to lie flat on his back. He was a young man, only 42 years old. But he was hurting, lying a futon on the floor in the middle of the living room. I sat in lotus posture next to him, and we got acquainted. Maybe he saw something in me. I don’t know, but we got very close and very intimate.

“We sat there for many hours and for many days just in . . .” His voice chokes up, and his eyes tear. “It makes me cry. It was a very intimate time. He was so vulnerable. There was no hierarchy. The patriarch wasn’t there. He was just an ordinary, confused man whose back was killing him and didn’t know how to be a normal human being. He was trained in a monastery, became a monk at 13 or something like that. At 18 he goes to a temple and lives with Koryu Roshi. At 22 he finishes Kanazawa University, then two years at Sojiji Zen Monastery, and then he is sent to Los Angeles as a young priest of 24. He knows how to be a temple monk. He doesn’t know anything about the world and America and relationships. So he was a confused young man in some ways, and it touched my heart. That’s when he truly touched my heart.

“Maezumi Roshi was, in my opinion, as arrogant as I was. There was a story about when he met Suzuki Roshi for the first time in San Francisco, and Jakusho Kwong Roshi was there, who told me the story. He said after Maezumi left Suzuki Roshi said, ‘That’s the most arrogant young man I’ve ever met in my entire life.’ That is exactly what Roshi said about me. ‘You are the most arrogant young man I’ve met in my entire life.” Ditto! Two of a kind.

“Then he got married. I don’t know, things change. He became this hierarchical Maezumi the Roshi, never taking off the hat of the master. I think maybe four or five times in my entire life after that first year did he put aside that role. In 2009 or ’10, I was teaching a workshop and his wife, Ekyo, was there, and I made that statement, and she says, ‘Wow! For me, six or seven times.’”

Genpo studied with Maezumi for nearly twenty-four years.

“I went out on my own in ’84, started sanghas throughout Europe. France, Poland, Germany, England, the Netherlands. And in ’95, Roshi dies and in ’99 I had this notion from way back in ’73 when I was living in Santa Barbara how in China Daoism and Buddhism became Zen. Before that it was just Buddhism. I felt that in the West the marriage was not going to be with Daoism but with Western psychotherapy.”

After Maezumi died, Genpo worked with Hal Stone on the Jungian concept of “shadows.” Stone is the founder of “Voice Dialogue.” Genpo describes calls him “my mentor – not teacher, mentor – after Maezumi died.”

“I had shadows like the rest of us. So many shadows, oh, my God! Everything we think is Zen, as enlightened and as right, we disowned their opposites. So I felt very spiritual, very awakened. I believed I was not competitive; that was a shadow. I was not greedy, another shadow. I was not hurtful and not mean. I was not un-loving. Those were all shadows. We believe we are enlightened so we disown all that we believe is not what an enlightened person would be, and all these aspects of our self that we disown come back as saboteurs. They undermine our lives and the lives of others.

“One time Hal was working with Maezumi Roshi, and he asked Maezumi, ‘May I speak to the voice of anger?’ And Roshi said, ‘I don’t get angry.’ Which we all knew was bullshit. Hal said, ‘We all have a voice that’s called “anger.” Can I speak to it?’ And Maezumi said, ‘I don’t get angry!’ That’s a shadow. We all have shadows. It has been my lifelong project since then to reveal my shadows and bring them to light. Because otherwise we are really unhealthy, we are harmful to ourselves and others. We all have shadows. Nobody gets away without shadows. And if we’re willing to look at those shadows, that’s one thing. If we’re ashamed of those shadows, if we deny that we have shadows, if we disown that we have shadows, we’re really kind of screwed. And if Zen is to take root in this Western world, those shadows must be revealed to us. We must look at and recognize them, we must look into ourselves. We must do what Dogen Zenji says, which is ‘To study the Buddha Way is to study the self.’”

I ask how he believes his teaching differs from Maezumi’s.

“Many, many, many, ways. The root is the same. The core realization is one. But the way that we manifest it, the way we teach it, the way that we approach it is completely different. That was his beauty, the uniqueness of every one of his twelve successors manifested differently.

“The difference? I’m really interested in shadows; Roshi wouldn’t even know what that term means. I’m interested in where we’re stuck. Roshi’s interest was if we’re stuck, we didn’t sit enough. His answer to everything was, ‘Sit more.’ My answer is, ‘Work on yourself. Look at where you’re stuck.’”

“And when people come to you as a teacher,” I ask, “what are they looking for?”

“I don’t know. Everybody comes for different reasons. Some come because they want to become a Roshi.”

“That’s a career goal people have?”

“Some of them probably do. They come because the want to become a Roshi or an enlightened being. Or some come because they’re all screwed up. Some come because they’re hurting and in pain. They all come for different reasons. I can’t say why they come to me. But when people do come, they’re all looking for something, and I take each one as they are, who they are, and I try to work with them from that place. Not necessarily to give them what they want but eventually so that they can have what they want. Which I think, in the end, is to be free, at peace, happy, and joyful. I find very few Buddhists are free, at peace, joyful and happy. The Buddhist world is – in my opinion – often miserable and unhappy. Clinging to a lot of ideas and notions of what it means to be a Buddhist monk or a Buddhist. Buddhism is hurting in the West, and we need to recognize the elephant in the room if we want to breathe life back into it.”

“What’s killing it?”

“Ideas and notions, our Western notions and ideas. We’re very different than the Chinese or the Japanese or the Indians or the Koreans. We have lots of notions about what is right and wrong, or moral or immoral, or what’s good or bad. That was not the same in Asian cultures. They had Confucianism. They had Daoism. They had Mencius. They had a form of Zen that wasn’t conditioned by Western psychology or Western Christianity or Western Judaism.”

“Okay,” I say. “I wasn’t sure I was going to go here, but it looks like we got there anyway. You’ve got a reputation.

“I have a reputation.”

In the late ’80s, Genpo was the abbot of a Zen community in Bar Harbor, Maine, which dissolved in part because of an affair he had with one of the members. Again, in 2011, while abbot of the Kanzeon Zen Center in Salt Lake City, he admitted to a number of extra-marital relationships, and – responding to calls for his resignation – announced he would disrobe as a Buddhist priest and withdraw from teaching. A few months, however, later he reversed his decision, arguing that too many people depended upon him spiritually for him to be able to do so. That led to the letter with the sixty-six signatures.

“Why do you think the things you’ve done bother people so much?”

“I really can’t answer that question. I’m sure it came to a head in January 2011 and has to do with my infidelity up to then. It may also have to do with who I am, my personality, and of course who they are. However, I am grateful to those people who gave me a good reason to take a long insightful look at myself and my own shadows. Because of my past catching up with me, my karma, and they being upset with me, I saw I had allowed myself to become intoxicated with my own power, and I got stuck there. And in doing so I harmed and hurt people, people I love, people I care about, and my Dharma successors. I certainly am not proud of my behavior and my immaturity thirteen-fourteen years ago. It has caused a split among my successors, which I would love to heal if possible. It has forced me to look deeply into myself, to take responsibility for my past actions, and to live and act with integrity and honesty, which I was not doing prior to January 2011. And I am very grateful for that.”

“Are things different now?” I ask.

“Very different. I feel very free from the Soto Zen School and from organized religion. I feel free, happy and grateful for the Zen lineage I come from. I live as a monk, not as a monastic monk or priest but as a hermit monk. I live here with my wife on the largest active volcano in the world, on the Big Island of Hawaii. Sometimes she’s here and sometimes she’s at our home in Oregon near my daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter in Newport. So I live here alone about half the time, and half the time with my wife.

“I’m a very private person in a way. I don’t have many friends on the island. I have some acquaintances, a few friends, but mostly I’m alone or with my wife and doggie, Kaya. And I teach in the mornings over Facetime or Zoom, and I have – I don’t know – about fifty personal students that I spend a lot of time with on video. They come and visit me here. Spend a week with me. We study together. Sometimes they come in groups, and we study as a group. The rest of the time, once a year we do a sesshin on the mainland. I still have several hundred students who are not as active, but a lot of people call me for help or follow me online.”

3 thoughts on “Genpo Merzel”