Ordinary Mind Zendo, New York –

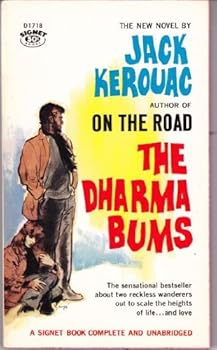

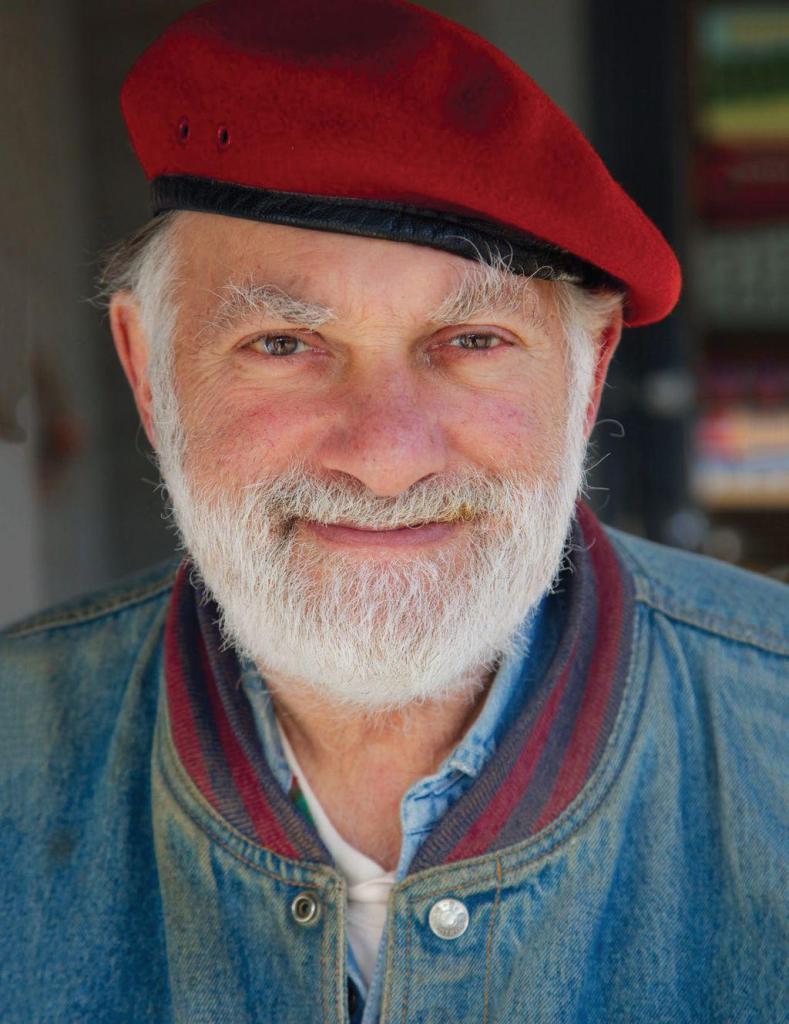

“Like a lot of people in the 1960s,” Barry Magid tells me, “I encountered Zen through the Beats, in reading Kerouac and Gary Snyder. I found Alan Watts and D. T. Suzuki and those folks. So at some point I noticed the characters who were still alive – who didn’t drink themselves to death – were the ones who actually began practicing. And by the time I was in medical school, I started to try to find out some way to begin practicing.”

It started when his college approved a three-month course of study at the Associates for Human Resources in Concord, Massachusetts. “It was trying to be Esalen East. Jack Kornfield was on the staff. They did all this Gestalt training and encounter groups, Reichian analysis, and TM. All sorts of stuff like that. They brought in Gregory Bateson and Bucky Fuller. I can’t believe I got medical school credit for it,” he says, laughing. “I think Jack Kornfield taught everybody walking meditation.”

“What prompted you to take that on?” I ask.

“Well, you know, very early on I was interested in mixing up psychoanalysis or psychotherapy and meditation practice. It looked like these were two profound systems of character change, but it didn’t look like they were communicating with each other very well. I wanted somehow or another to put those two things together. And there were a few things pointing me in that direction. Alan Watts was trying to be psychologically minded. We were reading books like The Freudian Left by Paul Robinson, and so there was a whole counter-cultural mixture of those things. If you were reading Wilhelm Reich you were probably reading Jack Kerouac and reading about Gary Snyder. So it was like, ‘How are you going to put all this stuff together?’”

“I can see the interest as an academic subject of study, but what drew your interest to meditation as a practice?”

“I don’t know. It was probably the spiritual equivalent of, ‘I’ll have what she’s having,’” he suggests with a chuckle. “You know, you read these idealized pictures of Japhy Ryder in Kerouac, and you say, ‘I want to be one of those guys.’ Right?”

Like his other books, Kerouac’s Dharma Bums is a roman à clef. The central figure, Japhy Ryder, is a thinly veiled portrait of the poet, Gary Snyder. Kerouac’s portrait of Ryder is exuberant and appealing—a Zen practitioner, an outdoorsman and poet; a scholar, in addition to being both sexually accomplished and wise in the ways of the natural world. “He did not look like a Bohemian at all,” the narrator of the novel notes; instead “he was vigorous and athletic.” It was a portrait which would intrigue and inspire many young readers. Barry was in his early 20s when he read the book. It would still be a while, however, before he took up formal Zen practice.

“So maybe towards the end of my residency, ’77/’78. I applied for analytic training. I tried to find an analyst who had some sympathies with Eastern ideas, and I started going to Eido Shimano’s Zen Studies Society three times a week and my analyst three times a week and did my best to get them all mixed up.”

“Was it a successful mix?”

“Well, I’ve made a career of mixing those two things up ever since,” he says with a laugh.

“In some ways, I was probably precocious as a meditator, and something quickly grabbed me about that. But it was also the case that these were the days of the big scandal with Eido Roshi who was sleeping with his students. You know, at one point somebody took red paint and wrote ‘shame’ on the front door of the place. There was a big exodus of people. It quickly became clear that enlightenment might not be all that it was cracked up to be, that there was clearly character pathology that was not washed away by the enlightenment experience, because the idea at the time was that you just had to have a big enough enlightenment experience, and it would be a sort of a universal solvent for the ego and all its problems. But when you have the teacher being the one having all these unresolved problems, something isn’t computing. So there was a way in which the problem of dissociation was clearly manifesting itself, and that made it all the more important to try to determine what’s the relationship between meditation and western psychology and therapy.”

Barry withdrew from the Zen Studies Society but not from the practice.

“Then Bernie Glassman came to town. People at the time referred to him as the Great White Hope. He was going to be the Westerner who had received Dharma transmission and was going to be an alternative to Eido and having Japanese teachers. So I spent some time in the ’80s with Bernie. Did koans with him for a while.” Barry was also, by then a practicing psychiatrist.

Bernie founded the Zen Community of New York in 1980. Barry tells me. “It was fun. But it was a complicated place. It was running on its own mythologies. But it had an interesting group of people there. Lou Nordstrom was a good friend. Peter Matthiessen. Larry Shainberg (the brother of my analyst at the time, David Shainberg) and Diane Shainberg (a brilliant woman and one of my instructors during my analytic training and also my analyst’s ex-wife). There were a lot of smart, interesting people hanging around Bernie in the early ’80s. And he started out saying he was going to have this kind of open community with some residents but lots of people coming in. It wasn’t monastic. Although at some point Bernie told me, ‘If you’re really serious, stop being a psychiatrist and come here to practice fulltime.’ That was a non-starter. And then he had the idea of running a bakery, which ended up destroying the community because the work-practice just took over the place. There had been this big community center in Riverdale which they then got rid of, and they just moved up into Yonkers for the bakery, and that whole thing imploded.”

Bernie started the Greyston Bakery two years after the Zen Community. It has been admired by many as an example of social enterprise, but Barry found it problematic.

“That was a real disaster as far as I was concerned. Everything got shifted towards work practice. And for a lot of people, it was just a lousy low-paying job. It wasn’t practice. The whole center of gravity of the place shifted. And – as Bernie often does – he sort of got in over his head financially and then asked everyone to bail him out. He tended to be somebody who got very enthusiastic about projects, took them a certain length for a few years and then moved onto something else, and a lot of people felt left in the lurch by that.”

It was something Bernie himself was aware of. When I met him in 2013, he told me that he thought of himself more as an entrepreneur than a businessman. “I’m not a great person to run a business, but to start one! I’m not sure what year, but one year I was voted by US News and World Report as the social entrepreneur of the year.”[1]

“He was charismatic and high energy and made things happen,” Barry told me. “But he was not somebody to establish a stable community, and I think that’s much more what I would have wanted.”

Barry does not view the teachers with whom he worked with an uncritical eye. He points out, for example, the tendency for there to be – as he put it – “a dissociation between the psychological life and the spiritual life.”

“What is the difference between them?” I ask.

“Well, there shouldn’t be any but what happened was that it turned out to be a big split in all these characters. Eido and Daido Loori and Bernie would tend to talk about the ‘merely psychological.’ Those were the kinds of problems you should go get cleaned up somewhere else, but we were going to explore some more essential truth. And that, I think, was just very split off. I remember in the Eido Roshi days, I talked to somebody who was one of his Dharma successors; he said, ‘I think of Eido as like a great musician or conductor. He creates this fabulous music, and what he does in his private life should be irrelevant.’ And I just thought that was utter nonsense. I said, ‘What is the music a Zen teacher creates if not an ethical life?’ What is the teacher’s talent for? That you get to answer koans? What does that correlate with if it doesn’t correlate with compassion, if it doesn’t correlate with a sense of personal well-being and how you treat other people? So the idea that there was this kind of beautiful insight that you’d get through meditation and if you’re screwing all the students on the side or you’re getting drunk all the time, well, we can brush that under the rug because there’s this beautiful thing you’re contributing. Well, what the hell is it? What’s that for? That just ended up seeming specious nonsense to me.”

After the focus of Bernie’s group turned to the bakery, Barry was among the participants who withdrew.

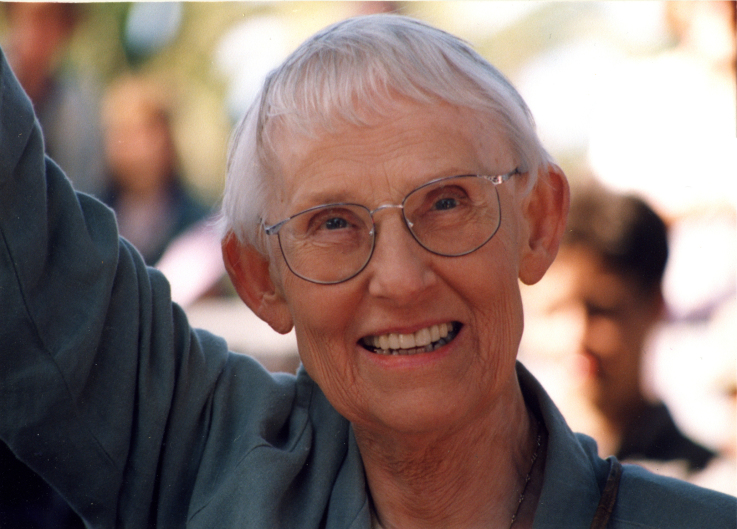

“For a few years we had a sort of a peer sitting group in Manhattan run by a wonderful woman potter named Nora Safran. She’s not alive anymore, but she was a wonderful potter. She had been around in the days with Yasutani Roshi and Soen Nakagawa in New York before me. But she was sort of a fellow refugee. And she had a big loft where she had her studio. Larry Christensen was there at the time. He had been a student of Maezumi’s in LA, and I guess he knew Joko Beck from the LA days, and he had been going out to see her. He persuaded her to come to New York to lead sesshins for us. I remember the way we got her to New York was we got her tickets to the US Open. She was a big tennis fan. That’s how we bribed her to come lead sesshin. So she did that a few times. And I very quickly hit it off with her and started going out to San Diego several times a year doing sesshins with her.”

“You were still resident in New York and commuted to San Diego?”

“Yeah. It was a hell of a thing to do. But, as they say, it seemed like a good idea at the time. It must have been about ten years of that.”

“I know from personal experience, living 500 miles from Montreal where I worked with Albert Low, that travelling some place for sesshin – even regular sesshin – is different from living there and being part of the sangha,” I say.

“Yep. Yep. That’s right. Although Joko didn’t have a residential place.”

“No, but she had a local community.”

“She had a community there; she had a sangha. But there’s also a way in which Joko liked people to be independent. She didn’t like the idea of people becoming too tied to her. So I think the fact that I could come and go was sort of a plus. It was a funny thing. But that was practice that was much more grounded in emotional honesty than doing koans. She completely repudiated koan practice after her experience with Taizan Maezumi. She felt koans did not engage any of the emotional reality in his life and his student’s life. And she just wanted no part of it, although once in a while I could bug her and ask her about one if I wanted to. But she was really very sour on all that.”

“She was soured on Maezumi in general,” I note.

“Well, he had an affair with her teenage daughter while she was a student there. His behaviour was just unconscionable as far as she was concerned.”

“There are several of these people in the history of American Zen, people who have less than stellar personal lives.”

“That seems to be a theme,” Barry agrees, “And so what I’ve been writing about and trying to teach are all the dissociative pitfalls or curative fantasies that come up in practice. In part, it’s been a kind of acknowledgement that Buddhism – or Zen – is not a timeless, ahistorical revelation or universal truth. It’s a cultural artifact that was devised in a community of celibate, ascetic mendicants, and psychological well-being was not high on the list of things they were trying to achieve. So I don’t feel any fundamentalist allegiance to this ancient truth. I think it’s a method that we’re constantly trying to adapt to a new reality.”

Barry received transmission from Joko in 1998.

“I feel like I’ve inherited a tradition,” he tells me. “I’ve embodied it after my own fashion in the present, and, as a teacher, I have a responsibility to pass it along. But I’m passing it along not unchanged. I think that’s part of what Dharma transmission is. Joko did not pass on unchanged what she got from Maezumi, and I don’t pass on unchanged what I got from Joko. So it’s not this sense, again, of a timeless truth.”

“You pass on what you received from her ‘not unchanged.’ What is it that you received from her?”

“Are you asking, what is the essence of her teaching?”

“The word used is ‘transmission.’ Something is transmitted. So what is the essence of the thing that’s being ‘transmitted’? What are you transmitting to your successors?”

“What I ask for from my successors is a psychologically minded Zen practice. So what I’m interested in is a kind of psychological wholeness where the point of the practice is to be able to own all those parts of yourself that you came to practice to get rid of. Your vulnerability, your anxiety, your anger, your sexuality. There has to be someway in which you can look in the mirror and say, ‘This is me.’ We’re not here to create an idealized version and then push everything aside.”

“That’s what you’re doing, but what I asked was what’s being transmitted?”

“What’s transmitted is, very literally, a practice – a practice of sitting – and of an orientation to sitting that is, again, not about the cultivation of particular states but the owning and acknowledging of all states and of everything that’s coming up.”

“And the value of that is?”

“The value is that basically character-pathology is the result of an endless attempt to fix or extirpate the parts of the self that you think are the source of suffering. But that whole processing/fixing/excluding is the ego that’s causing the problem. So psychoanalysis and Zen and Wittgenstein’s philosophy leave all these things just as they found them. Right? But that’s the thing we can’t tolerate doing. We don’t know how to leave our self as we find it. That is the dynamic engine of the suffering, that sense that I have to extirpate my anger. I have to extirpate my sexuality or my anxiety.”

I wonder if this doesn’t give an out to people like Eido who, I suggest, could have discerned that being a philanderer is just part of who he was.

“Well, that is not just, ‘This is essentially who I am, like I have brown hair and blue eyes.’ I think these habits have long histories and dynamic forces that generate them. It’s like saying, ‘I’m just angry’ without looking at how your expectations, your need to control, or your emotionally vulnerability leads to anger. You can’t just take anger as a simple given in your personality and say, ‘That’s just who I am. I’ll leave that alone.’ That’s either blind or dishonest. And I think somebody like Eido, his need to seduce and control people and to have that kind of narcissistic gratification is not just a given of his personality. It’s the end point of a whole history that was split off and never engaged with his Zen practice. One of the pernicious byproducts of some realization experiences is that they basically say, ‘Doing this, I can feel really wonderful without dealing with any of that other messy psychological stuff. I can just keep doing this and feel better and better and more and more okay in this one compartment.’ But I’m not dealing with any of the things that make me want to go out and get drunk at night. So there’s a way in which these dissociated parts of the personality don’t get swept into the hopper sufficiently. And that’s what Joko was mostly trying to do, make you engage all of it. Not cultivate one piece of it and split the others off.”

“Earlier you questioned the value of this practice if it doesn’t lead to an ethical life.” He nods his head. “What’s the value of an ethical life?”

“There’s no value outside of that. That’s what value is.”

I wait to see if he will add more to that statement, and, when he doesn’t, I say: “We have already mentioned several teachers who couldn’t have been said to have led particularly ethical lives. There are others of course. Have all these distorted the tradition they’d been entrusted with passing on?”

“No, I think they actually exemplify the tradition. I think the tradition was such that dissociation is not a bug; it’s a feature. That’s why I said I don’t think that traditional practice thought about or was very good at dealing with psychological issues. I think culturally certainly a lot of the Japanese teachers came from a tradition where very explicitly what you do in your private time doesn’t matter – that there’s the daytime personality and then the go-out-drinking-at-night personality – and they’re very comfortable culturally with that kind of split. And I don’t think it was as if there were these wonderfully, psychologically healthy teachers in a previous generation and these guys just fucked it all up. I don’t think it was a practice made to deal with that stuff in the first place, and America exposed that.”

“Regardless of which, you remain loyal to the heritage as it was transmitted to you.”

“It’s like psychoanalysis. I’m not a Freudian but I’m a psychoanalyst. You feel that’s part of what being part of a tradition is. There’s a whole stream that gets you to where you are today, and, of course, the people who came before you were dealing with things in different ways than you’re dealing with them now. But you can still be part of it without feeling like you have to do what they did or feel like what they did had to have been perfect because they’re the forefathers.”

“Why do people take up Zen practice now? A lot of people our age first came to Zen because they read Kerouac or they read Kapleau and they wanted that enlightenment experience which was going to miraculously redirect their lives. But what do people come to Zen for now?”

“Well, I say that almost by definition everybody comes to practice for the wrong reasons because you’re coming with all sorts of self-centered preoccupations. Everybody’s got that, and they are bringing whatever it is to that. These are what I call peoples’ curative fantasies. And I think the people who come to the zendo, and the people who come to my psychoanalytic practice are, a lot of the time, interchangeable. I think the Zen people these days are more likely to come for psychological problems than as kensho seekers. I think there’s less of that in this generation and just more overt looking for some kind of psychological well being.”

“What kind of psychological well being?”

“I’ve talked about these things in different kinds of categories. There are the spiritual anorexics, the ones that are seeking purity and want to shed the parts of themselves they think are greedy or needy or vulnerable. Then you get the people who have taken a vow to save all beings minus one. They’re the compassionate do-gooders who don’t know how to deal with their own needs and often come to practice as a way to escape their own needs into what they think is going to be compassion. And then there are the people who are looking for mastery. That happened more in the Rinzai crowd, where you want to have people that are so tough nothing will ever perturb them again. They will be able to master any situation. I can sit seven-day sesshin, I can handle anything. Right? I’ll be the toughest son-of-a-bitch in the valley. So you could say that, just like in psychoanalysis, people all come trying to perfect their own neurotic solution, take it up a notch.”

“So they come for the wrong reason, and what do they discover if they stick around?”

“Well, we try to make explicit what that wrong reason is and where it comes from. Why do you try to get rid of this aspect of yourself?”

“Okay, suppose one of the people we’ve mentioned woke up one days and thought, ‘The way I’m going, I’m hurting people. I’m harming others. Maybe I better go see somebody, try to get help.’ And they come to you. What is it that you could help them with?”

“Trying to tolerate the vulnerability in themselves that they’re trying to compensate for with this behaviour.”

“And do you expect that behaviour to alter as a result?”

“Yes. That’s what the point of therapy is. You expect some of that to alter if you see that it has a cause, and you can begin to deal with it.”

“You’d said that some people are drawn to take up practice because they identify what they consider greediness or neediness in themselves. Is getting rid of that greed a reasonable end for this process?”

“Joko used to say that the point of practice is to learn to suffer intelligently.”

I hadn’t heard that quote before and smile. “That’s a nice line.”

“I’ve added that it’s also to learn to become dependent intelligently. What is your relationship to others; how are your needs expressed; how are you going about that without putting all the neediness into other people so that you can always feel like you’re the strong one? That’s a very typical teacher syndrome. I’m the one with the answers; I’m not the one with the needs. So we have teachers having affairs with students because this was the one place they finally found someone they themselves could be vulnerable with, and they could be on the receiving end of something. See I remember, certainly in the old days, we were always told about how important it was to be compassionate. Right? But the arrow always went in one direction. I never heard anybody talk about the need to receive compassion, to need love. It was always, ‘You have to give this. You have to give this.’ Teachers – you know – often need to be at the receiving end of it, and, if there’s not a legitimate way to do that, they start doing it illegitimately.”

[1] Interview July 15, 2013