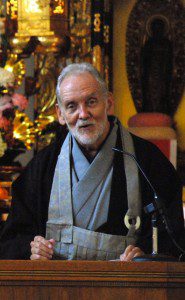

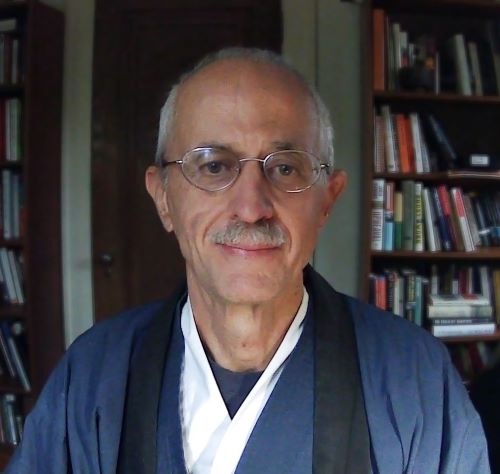

Cold Mountain Sangha, New Jersey

“I’m from a mixed background/heritage, and religion really wasn’t an important part of my upbringing,” Kurt Spellmeyer tells me. “I became interested in all kinds of religious traditions, but it wasn’t part of our family’s experience.”

I ask what the mix was.

“Well, I was really ‘all of the above’ and ‘none of the above.’ Protestant, Catholic, Jewish. But my grandparents on both sides were irreligious, indifferent, or actively opposed. Every once in a while, my mother would become anxious about our well-being and send us some place for a little while, but then my parents didn’t have the follow-through to make sure we kept going. When we lived in Bowie, Maryland, I went for a while to Hebrew class after public school, but I thought it was boring and I asked my mother if I had to go. She said no and sent sent my bother and me to a Presbyterian church, but my brother got us expelled for making fun of the ‘Tell Me the Story of Jesus’ song. My early experience of religion was eclectic, even incoherent, and I’m actually rather glad about that, that we didn’t have a religious Tradition with the capital T. As an undergraduate at the University of Virginia I double-majored in English and anthropology, and I became fascinated by the anthropology of religion, symbol systems, and so on. My background allowed me to follow my interests without feeling that I was betraying any particular position, and I think that was the best place for me to be. For me, the lack of religious commitments was liberating; I felt free to explore.”

He acquired an undergraduate degree in Virginia and then went on the road. “I grew up reading Jack Kerouac. When I finished my undergraduate degree, I was dying to see more of the country, so I hitchhiked across the United States, from the East Coast to the West, and from Seattle down to New Mexico. I worked periodically—as a carpenter, a housepainter, a cook, and moving furniture for the Mayflower company. And I loved that life. I was a pretty good carpenter, by the way, and I became a member of the union when I was working in the Northwest.”

After a few years he entered the graduate program in English at the University of Washington in Seattle, but it wasn’t an easy transition.

“The demands were stressful. While I was out exploring the world, my academic skills had gotten rusty. I probably hadn’t read a book in three years. Then, abruptly, I was in graduate school, competing with people who had just arrived from Harvard and Stanford. My professor would quote Heidegger, and some of the students would say something back in German! I felt so outclassed and ill-equipped. I was trying to adjust to that environment and beating myself up, which only made things worse. And I was almost always on the edge of broke. Then, my wife somehow heard about a Tibetan center near the university. You remember Chogyam Trungpa? This center was a part of his organization.”

“Shambhala?”

“Shambhala, right. They owned a house on Forty-fifth, and I started going there to sit when it was open in the afternoon. I’d read some books on meditation in college and had done some sitting on my own, and going there definitely helped me cope. Then one day I ran into somebody who said, ‘You know, there’s a Zen master who’s just come from Japan, and he’s holding classes at the University of Washington on Wednesday nights.’ I immediately acted on the tip, and that’s when I met Takabayashi Genki Roshi. And I absolutely fell in love with him, and not only with him but also with Zen. For me, the practice of sitting was like nothing else I’d ever done. Absolutely wonderful.

“The first time I went over to the University looking for the Zen group, I was hoping to meet a ‘Master,’ whom I’d imagined would be something like Master Po in the television show Kung Fu. But when I found the room where the sitting took place, I saw this small, unimpressive Japanese guy mopping the floor. And I said, ‘I’m looking for Genki Roshi.’ And he replied, ‘I am Genki Roshi.’ That was such a wonderful moment. The enlightened teacher is mopping a floor! That was an extraordinary moment for me. I thought, ‘Oh, I’ve just met my teacher.’ I didn’t even know what that actually meant – to ‘meet your teacher’ – but there was just an immediate resonance. He checked many of the boxes in my unconscious, I guess, when it came to what an awakened person should be.”

“What were you looking for?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I don’t think people ever know. I mean, they can explain or rationalize their cathecting to a certain person as a ‘teacher,’” – I had to look up the meaning of “cathecting” later – “but I don’t think they can really know because so much about this relationship unfolds below the surface of the conscious mind on both sides, the student’s side and teacher’s. There’s a lot of projection on both sides, but those projections in my view come from a deeper place that deserves our respect. I would say that the enlightened mind in me spoke to the enlightened mind in Genki Roshi. In point of fact, I didn’t really know the guy at all, at least not at first, but already there was this subconscious or unconscious resonance that was absolutely clear to me.”

“That’s the way you understand things now,” I remark. “What did you feel then?

“Just this trust. Just this rapport. I admired his humility, his unpretentiousness and naturalness. He never struck me as menacing or judgmental. And that mopping-the-floor moment was a wonderful introduction to this person. I’m convinced you can’t know intellectually what the teacher-student relationship involves; it’s a powerful intuition you simply have. At the moment of our first encounter, I saw Genki, but I also saw something beautiful and enlightened in myself. In a way, it’s really not about the teacher.

“At this time, I also had the opportunity to meet Sensei Glenn Webb, who was a professor of art history and the founder of the Zen group.” Kurt would eventually receive transmission from Webb.

He began a regular practice with the Zen group. “I was getting up at 4:00 every morning and going to the Zen Center and sitting for an hour and a half. I often sat in the evenings as well, but, in the meantime, I was taking courses at UW and teaching classes and trying to write my dissertation. That was pretty demanding. Sometimes I was so tired I would just have to keep the radio on beside my desk to prevent me from falling asleep while I tried to grade my papers.”

“It so happens, I also have a Ph. D. in English,” I note, “so I have a sense of what that must have been like. And you’re getting up at 4:00 in the morning, plus doing occasional evening sits. Why? What were you getting out of this?”

“Well, it’s one of those things you don’t need to explain because explanations are beside the point. Why do people backpack or climb mountains? What really matters, I would say, is the resonance or the character of the energy that arises when you take a certain path. You feel more alive and more connected. The quality or tenor of your life has changed.

“Lots of people tried to dissuade me,” he adds. “One time I went to see my graduate director, and I had my zafu, and he asked, ‘What’s that?’ And I said, ‘I belong to a Zen group here, and I’m just going to do meditation.’ And he said, ‘How often do you do that?’ And I said, ‘I do it every day.’ He was actually angry at me. He said, ‘You know, you’re throwing your career away with this cult.’

“In Zen we talk about your ‘True Nature,’ and I think that when people don’t listen to their True Nature, that’s the worst mistake they can make. I have been very confused in many ways in my life, but when I found that connection, I knew that I needed to act from there. You sit down on the cushion, and you simply know. That’s been the truest thing in my life. I get up every day and do zazen.”

“I’m still curious about how it helped you,” I persist.

“Zen has solved many of my problems. My anxiety problems went away. For some reason, after sitting for a few months, I felt much more confident and grounded. I wasn’t so caught up in my mental loops. I was able to do things that I probably wouldn’t have done without Zen, like completing my Ph. D. and landing a job and getting tenure at a highly competitive research institution. But even if it hadn’t done those things, this is still something I had to do.”

There were some tensions in the Seattle group. Genki was identified as the teacher because – Kurt tells me – “Glenn didn’t want to play that role. Webb’s first teacher, his Dharma father, Miyauchi Kanko, had wanted him to stay in Japan and develop an international Zen center at Kankoji, an Obaku Zen temple which is now defunct. But Webb chose to return to the United States, where he started the Seattle Zen Center, which he invited Genki to lead, and Genki Roshi only came to the US because he was disgraced back in Japan. My understanding is that he was initially regarded as a rising star in the world of Rinzai Zen, but he had an affair and then, when the woman became pregnant, he refused to marry her. After that, she went to the Rinzai authorities who called him in and laid down the law: ‘Look, Genki, the way to handle this is for you to marry this woman’ But he categorically refused, and that was the end of his career in Japan. Here, in the United States, I think at first he behaved quite well. But imagine that you’ve just come from Japan. You have all these adoring people around you, and they’re treating you like a god and that includes some very attractive women. Genki had been adopted as a child by Yamamoto Gempo Roshi; his Dharma father was a famous Zen Master who didn’t know anything about how to raise a kid. In fact, Genki was forced to attend sesshin when he was twelve years old, wishing an earthquake would pull the temple down on his head, as he once told me. So, imagine that this is your background and you’re suddenly in the United States with the Sexual Revolution underway. So he had another affair here in the US, and my understanding is this woman also had a child.”

Kurt admits that although he was drawn to Genki almost immediately, his relationship with Glenn took time to build.

“At first he was just the translator and someone who seemed a bit stiff and remote. And when he began to publicly express his disapproval of Genki’s behavior, I felt like punching him. But gradually I saw him in a very different light. I realized that behind the scenes Glenn had been the one who made everything happen. Before we had our own place to hold retreats, Webb was the person who would spend his Saturdays driving around Western Washington looking for sesshin venues, negotiating costs, and settling up with whoever was renting us the facility. He was like Kannon with a thousand helping hands, never getting the bows that the Roshi received but teaching us in a less visible way. Somehow I finally noticed.

“Glenn was a Congregational minister’s son who got interested in art history and went to the University of Chicago where he received a Ph. D. is Asian art. And he got involved with Zen by accident. He’d gone with the intention of studying several famous Zen paintings, but when he went to the temple where they were kept, and teacher there had told him, ‘I’ll show you the paintings, but you have to do zazen.’ He eventually took priest’s vows, but I think that for most of his life he remained conflicted. He had a deep respect for Buddhism; he lectured in the summers at Bukkyo University, a Pure Land institution, and he even became a tea master who taught at Urasenke. He had studied with Shin’ichi Hasamatu and the Kyoto School. But he also had a deep attachment, I believe, to Protestant Christianity. He often said that both of these traditions enriched each other for him, but I think there were also conflicts there that never got fully worked through.

“At any rate, when Genki had the affair, that crossed a red line for Glenn, and eventually our group split more or loss in two. You know how divisive these events are. Whatever the initial issue might be, it becomes a focal point for other tensions and jealousies. And so it wasn’t just an argument between two people but between different groups within the community.

“When the split happened, somewhat to my own surprise, I went with Webb. I suppose I went with him because he was a deeply ethical person, thoughtful, kind and sensitive. As you know, Protestants are no more ethical than anybody else, as we can see from the endless scandals in the Protestant world, but sexual ethics are important to Protestants in a way that people from other traditions might not look at in the same way. Webb, coming out of that background, was deeply affronted by Genki’s behavior. For me personally, not so much. I was more troubled, even angered, by his indifference to the woman involved.

“At any rate, after we had our community Civil War, I went to practice with Webb. I was ready to quit Zen altogether, the Civil War was so discouraging. People had to choose sides and were attacking one another, impugning each other’s motives. It was ugly and sad. People who had sat through sesshins side by side were suddenly yelling at each other. It was like a nightmare, and I’d had it. But all the same, Webb was organizing a sesshin. We had built a temple up in the mountains, which we were now about to lose because financial support had dried up, but Webb was going there one last time before we put the place up for sale. One evening after the meditation, Glenn approached me and asked if I planned to attend. And I wanted to say no, but when I looked at his face, I thought, ‘I can’t do this to him. He’s organized this last sesshin; I can’t say, “No.”’ And when I arrived at the temple, instead of our usual eighteen or twenty people, I think we had five, Webb and four others including me. Arriving at the empty, half-finished temple, I felt sad and lonely, but that was where I had my dai-kensho, my great awakening experience. It was like nothing else ever. I think I cried for seven days, and at first I wasn’t even aware that I was crying. It was the most real, powerful, transcendent experience of my life. And after that, I changed my plan about quitting Zen and trained with Glenn for another year until he said, ‘You’re done.’

“Around this same time I landed a job here in New Jersey at Rutgers University. I left Seattle, and I came out here to New Jersey where I struggled to get tenure at a really competitive place. Then my father, from whom I had long been estranged, died of cancer – in my arms, in fact – and I went to his funeral. As it happens, he was – who knew? – a member of the Masonic Order. And a contingent of Masons came to his funeral, dressed in black suits and wearing white gloves. It was so weird, and I thought, ‘Who the hell are these guys?’ Then one of them came up to the front of the gathering and read from this little scroll, basically saying, ‘Life is short. Don’t waste time. This death is a warning and a sign!’ The speech just hit me, as they say, like a ton of bricks. I’d forgotten Zen! Of course, I’m very grateful to the profession of English for giving me a place in the world, a job that has meaning. I love teaching and I love literature. But Zen is my life. I couldn’t let it go. Painful as the history of the Seattle Zen Center had become, I had to return to Zen. So I wrote Webb, and I told him that I wanted to get ordained, and he said, ‘Great. Come to Malibu.’ He was living in California at that time, having left the UW for Pepperdine, a Protestant university. And he had created a new community there. So I went, and as soon as I got tenure, I started teaching Zen.”

“How did you get students? Posters on bulletin boards?”

“Yes. I just advertised in the student paper. And little by little people showed up.”

The community is called the Cold Mountain Sangha, referring to the temple in China named after the poet Hanshan – “Cold Mountain” – who probably flourished around 800 CE and to whom Jack Kerouac dedicated The Dharma Bums.

“This lineage goes back to Cold Mountain Temple in Suzhou,” Kurt tells me. “Glenn Webb’s teachers’ lineage goes back to this contingent that came from China in the Ming Dynasty.”

I ask, “What brings people to practice with you?”

“I don’t know.”

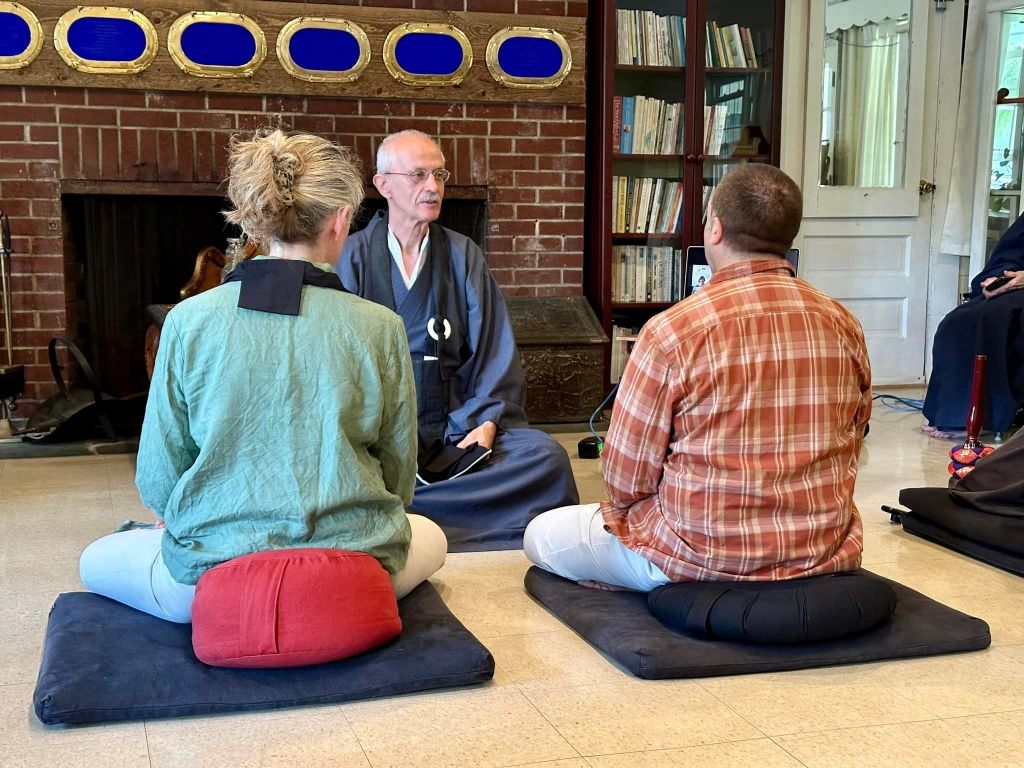

When I suggest he probably has some idea, he insists, “No, I really don’t. I don’t know what they’re looking for. I’m not being cagey. I never think about that. I just say, ‘Here’s the practice.’ My job is to make the practice available to them and to practice deeply myself. The only thing I can show these people is my sincerity. So I’ll show them how to sit; I’ll sit with them. If they want to do dokusan, I will help them work on their koans. Right? You know, if they persist, that’s wonderful; if they don’t persist, that’s not my business really, why they stopped. And I don’t think people themselves know why they come to practice. If somebody had asked me when I was 23, ‘Why are you practicing Zen?’ I might have said, ‘Well, I have anxiety.’ But I don’t think I knew why I was practicing Zen. The impulse to practice comes from a deeper place. People don’t – they can’t – understand why they’re there. What I say to my students is this: ‘Something brought you here. Please listen to that voice.’ And I always add, ‘If you listen to that voice, you’ll never be disappointed.’ I’ve said that all my life, and I completely believe it. ‘You don’t know what brought you here. But listen to that voice. Be true to that voice.’”

“Let’s look at it another way. Say someone in your department or some acquaintance discovers you are a Zen teacher, and they ask, ‘What’s the function of Zen?’”

“I would say, ‘Please come and practice with us.’”

“And perhaps I’m open to that. But I’m also one of those people who, before I come and try it out, I’d like to know what its purpose is.”

“You know, I’m not going say. I refuse to say. I’d tell them, ‘There are lots of books on Zen practice; I can recommend some titles to you.’ But I refuse to degrade the practice.”

“Fair enough. And if someone were to say to me, ‘Oh, you talked with Kurt Spellmeyer. What’s he like? What’s his Zen like?’ What should I tell them?”

“‘You just have to practice with him.’” We both chuckle at that for a moment. “Do you know who Clark Strand is?” he asks. “He’s written a number of books on Zen, and in one he talks about hearing, while he was in college, about a Chinese monk who was living nearby. Clark found the monk and started practicing with him. Whenever Clark came to practice, the monk would simply sit there, doing what we would recognize as zazen. But he wouldn’t offer any instruction. For some mysterious reason, Clark kept coming back and didn’t know why, while the monk would just sit with him in silence. Finally, Clark finished college, and he left the monk. He eventually he made his way to Dai Bosatsu Zendo in New York where he spent time with Eido Shimano, another teacher with a troubled history. But Clark Strand said that years later, in retrospect, he could appreciate the depth and purity of the monk’s practice. I agree with that. Of course, when people come to practice with me, I don’t sit there in silence. I’ll give them pointers: ‘Watch your breath. Breathe from the hara. Have a straight back.’ But all the same, Strand was right. The monk taught Strand how to trust the part of himself which says, ‘You need to come to sit.’ Reasons just cloud the issue.”

One thought on “Kurt Spellmeyer”