Minnesota Zen Meditation Center –

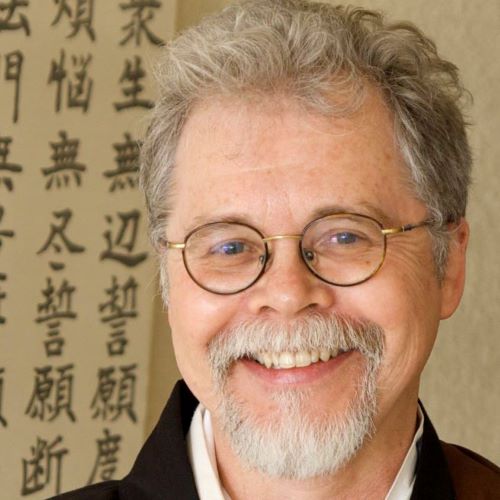

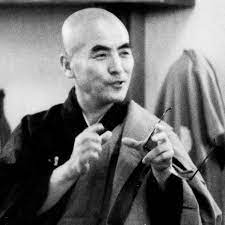

Ted O’Toole is the current Guiding Teacher at the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center in Minneapolis founded by Dainin Katagiri. It was a not an obvious location for a Zen Center in 1972. Dosho Port tells me that Katagiri had not been entirely comfortable with the hippies who were coming to the San Francisco Zen Center where he was assisting Shunryu Suzuki. “But there had been a small group of people who had been sitting in Minneapolis, and they had gone to San Francisco some. So he had some connection with those folks. A story he often told is he was flying from San Francisco to New York with Suzuki Roshi, and they were looking down at this vastness, and he asked Suzuki Roshi, ‘Who’s down there?’ And Suzuki Roshi said, ‘That’s where the real Americans are.’”

“As opposed to in San Francisco?” I asked

“Right,” Dosho says laughing. “So he was always curious. And his idea of a zendo was a place where plumbers and carpenters and millworkers, housewives and secretaries and teachers like that came rather than these poets and drug addicts and stuff.”

“And was that what he found in Minneapolis?”

“Ehhhh . . . When I first started there, it seemed like all the men were carpenters with Ph. D.s and all the women were social workers.”

At first blush, Katagiri might have considered Ted a “real American.” He grew up in North Dakota, in what he describes as a very conservative Christian environment. His family, however, were not church goers, and that, he says, “was a little troubling when I was child because I thought decent people went to church and we weren’t decent people, and I had some shame there.”

His first contact with Zen was reading Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums. “When I was young, I did a lot of hitchhiking, and when I came across On the Road, which was about hitchhiking, I really liked it. Then the second book by Kerouac I read was The Dharma Bums, which was the story of Kerouac’s encounters with Gary Snyder. It presented Kerouac’s particular take on Zen Buddhism, and, at the time, I thought, ‘Oh, so that’s what Zen Buddhism is like.’”

“Yab yum orgies and pot?” I ask.

“Well, yeah. Wild, spontaneous, just crazy things going on all the time, and when I first went to a Zen Center, I almost expected a couple of laughing monks to come rolling out the doorway when I opened it up. It was not like that. It was very tightly controlled. So I realized Kerouac had only given me a partial picture of Zen.”

“I’m guessing the book didn’t immediately inspire you to rush out and seek a Zen community.”

“No, it didn’t, but it did sort of start me on a spiritual quest. I had done some spiritual searching, and, when I was about sixteen, I sort of faced the idea of my own death for the first time, as we all do at some point. I had a friend who was a Christian, and he taught me about Christianity, and, for about six weeks, I tried praying and things like that, but it just didn’t take for me. It just wasn’t something I really believed, but when I encountered Zen – and I read other books about Zen; I didn’t stop with Kerouac – it really resonated with me. I thought concepts like ‘no self’ were things I could understand intuitively. And so I signed up for a course on Eastern Religions when I was at Grinnell College in Iowa. I actually dropped out of college a week after that, but I did go ahead and read all of the books for the course which was a survey of Eastern Religions, and Zen was always the one that had the greatest appeal to me.”

Interest in Eastern spiritual traditions was part of the cultural zeitgeist of the times. The Beatles had gone to study Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi in India, Hare Krishna devotees chanted in airports, and there were a lot of Hindu influences in contemporary art. It was also a period of great political strife in the United States.

“The Viet Nam War, of course, was the big issue. And through ninth grade, I was in favor of the Viet Nam War. Somewhere in the middle of the ninth grade – largely under the influence of my father, I think, who had this kind of revelation, which was pretty rare in North Dakota at the time, that the war was wrong – I started to seriously question the war, and it seemed like once you questioned that, you started to question everything, including all kinds of hierarchy and authority, and it kind of opened up new doors and new ways of thinking.”

“So the culturally conditioned perception of the world you had as a young North Dakotan began to shift?” I ask.

“I think that’s accurate.”

“Okay,” I say, “I can understand how even a young person in North Dakota might get that there isn’t a need to posit something external to creation in order to explain things. That the universe can be self-sustaining without theorizing something outside of it and responsible for it. That seems a relatively easy concept for a kid to pick up on. But you said the idea of ‘no self’ made intuitive sense to you, and that seems a pretty big leap.”

He reflects for a moment before replying. It’s a habit he has. “That’s not so easy to answer. I think that I somehow just had an intuitive sense about how the self is a construct. This is not something intellectual. It’s deeper than that and it’s beyond words. I think it naturally followed from that first time I faced the reality of my own death. Once I fully felt that fear, I began to look more deeply. What is this thing that dies? My thinking about this was pretty jagged, but once I came to Buddhism, these things were named, and I had a sense of recognition. I thought, these are the things that I’ve been vaguely feeling but have not been able to put words to. I learned about the five skandhas. And about impermanence, and the fact that things simply do not exist as continuing or independent entities.” He uses the classic example of a wooden ship. “If you replace a board now and then, and you keep doing that over years and years, eventually you don’t have a single one of the original boards. Is it still the same ship? That’s a pretty good simile to help us understand that what we call a ship is not a real thing. I, Ted, am not a real thing. And yet I’m Ted. That’s the other half of the story.”

He undertook a self-directed meditation practice for a while, but he didn’t actually enter a Zen Center until he was 30 and was attending law school in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I remark that 30 seems a little older than most people are when the begin studying law.

He nods. “Yeah. I dropped out of college. I did a lot of construction work, factory work. Did a lot of hitchhiking. Had a lot of adventures. And then when I was about 30, I got married, had a son, decided it was time to settle down, finish college, get going. It took me 18 years to get my undergraduate degree. And then I kept going and went to law school. And it was very, very difficult for me; it caused kind of a crisis. This is a story I’ve told many times to people here at MZMC. I was having a very difficult time at law school. In particular the public speaking aspect of it was really difficult. And when I was about five months into law school, I thought it was just too much. It was the class performance aspect of it that got to me, and I started having panic attacks in class. And I decided I would drop out. I was living in Married Student Housing, and one night, three nights after I had decided to drop out, I went out back of our house and sat on a hill in the forest, and I had a very deep spiritual opening. I was able to really take the self out of it, let go of my own ego, not think about whether I – Ted – was going to succeed or look like a person who was succeeding, not worry about any of that. And then I was able to go back and get through law school and fulfill my responsibilities. So that was one of the greatest turning points in my spiritual life. And some time after that, I went to the Ann Arbor Zen Center for the first time. That was the first time I’d ever been to a Zen Center or had a relationship with a teacher of any kind. So that was when my formal study began.”

The center was in the Korean Zen tradition.

“I was there for a year, and I loved the practice. I could take my son there because they had a family program. I would occasionally go there early in the morning and do 108 prostrations and a couple of sittings. And we would go there usually every Sunday. And I began a rigorous and dedicated meditation practice of about five minutes a day.” We both laugh. “And I would chant, and it just helped me a great deal. I would not have gotten through law school without it.”

“Helped in what way?”

“It allowed me to let go of the anxiety. When you’re panicky and worried about yourself and how you’re going to do, that’s really all ego, and this helped me to let go of ego and to just be quiet and centered. If I had something stressful coming up, I knew that if I would spend some time in meditation and allow myself to feel my feelings – as opposed to getting up in my head and worrying about it – I would be able to get through just about anything.”

“So you were using it more as a psychological technique than a necessarily spiritual one,” I suggest.

“I think of it more as a healing technique that was consistent with Buddhist practice. But, yes, absolutely, it was more about meeting my own personal needs at that time. My early forays into Buddhism were motivated by a spiritual longing, I would say, but what made me finally get serious about spiritual practice was a personal crisis and a need for help. That pattern is pretty common because – you know – Zen practice, Buddhism, there’s a great healing aspect to it. In a sense we don’t undertake it with goals in mind, but there’s a great healing aspect. After all, the Buddha’s reason for undertaking the practice was to end suffering. And the profound help that it gave me in ending suffering was really significant to me. I realize many people have had much more serious problems than I did having a hard time getting through law school – people have much more serious problems than that – but for me this was a deep crisis. I would have had to move my family back to Nebraska, and it would have upended my life. So it had a profound healing effect on me. But the spiritual quest was still a part of it throughout. Many of us come to Buddhist practice out of need, but then we stay in order to give. We can end up being grateful for our crises, for those were our entry points to the spiritual life.”

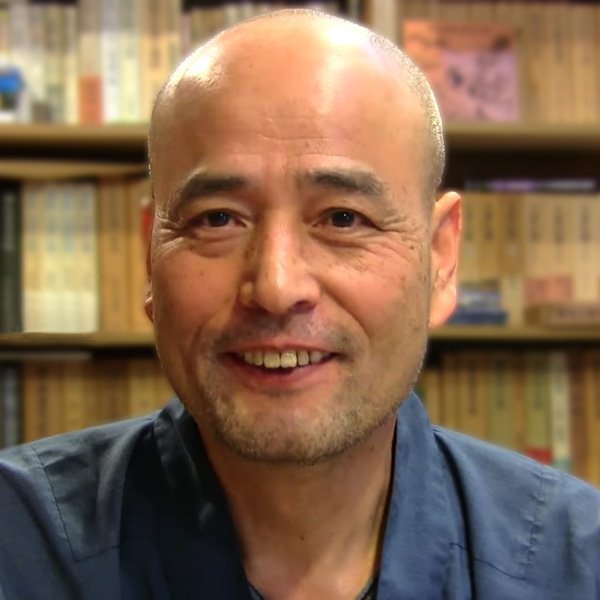

After completing his degree, Ted found work with a legal publishing firm in Minneapolis and came upon the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center. Katagiri Roshi was dead by that time, and the guiding teacher – Ted calls him the interim guiding teacher – was another teacher from Japan, Shohaku Okumura, who would go on to found the Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, Indiana.

“I was employed full-time, and I had a family, and I spent as much time at MZMC as I could because the practice was just very important to me,” Ted tells me.

“Important in what way? I mean, let’s say one of your family members back in North Dakota found out that you’d gone off and become a Buddhist. How would you explain to them what it was all about?”

Again, he takes a moment to think about his answer before replying.

“Life is a serious matter, not to be taken lightly, and I think it’s important to do everything we can to see it in its most elemental form and really get to know life, and that means going inside and understanding who we are. And to do that you need to be kind of deliberate and disciplined about it.

“And Zen provides a medium for that kind of deliberate and disciplined reflection?”

“Mm-hmm. It’s a way that people have been practicing for 2500 years, and it’s been refined over that time. I could probably have muddled through myself in some kind of introspection, but it would not have been the same as following this path and learning from the wisdom of others. And being challenged. It’s pretty easy to go off on your own and think you’ve found something and think you’re pretty cool if there’s no one there to challenge you and say, ‘Well, that’s great. But what about now?’ You know? ‘Lovely story of your awakening experience, but are you looking after your shoes?’”

Okumura was succeeded by one of Katagiri’s Dharma heirs, Karen Sunna. She was followed by her direct heir, Tim Burkett, who, in turn, would pass transmission onto Ted. During Okumura’s tenure, Ted took jukai, formally declaring himself a Buddhist.

“I gradually began to do more. And then around 2004, I developed this aspiration to be ordained. And that was . . . I mean, it’s an intensely personal thing to reach the point of wanting to do that. As I said, I was afraid of public speaking. I was really quite shut-down emotionally. But some things happened over several years of healing, and I got to the point where I had this moment of clarity where I could say to myself, ‘I could do this. I could become ordained. I could actually do that.’ Before then, I always thought, ‘That’s for other people, not for me.’”

He tells me he worked at the publishing firm for twenty-five years, during which time one marriage ended and a second began. I am curious about the balance of a lay career, family obligations, and practice. “Buddhism was originally a practice for monks, of course,” I say. “What’s its value for householders, for lay persons?”

“That’s a fascinating question. It was originally a monastic practice. We can see those monastic elements still at Zen Center, even though we’re a center which basically is made up of lay people. Even the priests live lay lives here. We’re not a residential center.”

“As I understand it, that was one of Katagiri’s goals in moving there, that he wanted to work with what he thought of as ‘ordinary Americans.’”

“Yeah, I’ve heard that. So he lived at the center, but everyone he served were living lay lives. I think that’s wonderful. What we are striving to do at MZMC is to help and guide people to live that really vivid lay life. It’s wonderful there are residential centers – we really need those kinds of things; we need full immersion in the forms and everything – but I like the fact that we are a non-residential center. And I like the way we’re able to fit into the life of our neighborhood. One symbol of this is, when we built a new zendo about three years ago, the architect – who was a practicing Zen Buddhist – designed a little window where we could see just a bit of the lake from the zendo. And folks in the sangha said, ‘Could we have a bigger window? How about we make that whole wall a window so we can see the lake?’ And we did that, and it was a great decision. We don’t have a zendo that shuts out the world; we have a zendo that welcomes it in. And I think that’s kind of a symbol of how our practice is here.”

“What did ordination mean to you?” He goes into another of his reflective pauses. “For example,” I continue, “if I become a Catholic priest, there are certain sacramental responsibilities but there are also pastoral duties. What did becoming a Buddhist priest ask of you?”

“I thought of those practical implications, but it was actually deeply personal. Something happened inside me where I realized that I could have a hope of being awakened in this lifetime. And before then I had never had the self-confidence or the self-compassion or the love perhaps to really believe that. So I really think it was a great opening of the heart that allowed me to think that I could do this.”

“Lay people can have that confidence and self-assurance.”

“Well, right. After experiencing such a healing on my own part, I wanted to share it with other people. That’s all I wanted to do. Like, what do we do in this life? We look after our families. We look after the people around us. And we try to bring joy and healing practices to others. What else matters? You could become famous, or you could become rich or something, but that’s a waste of time. What is important? What’s important is to be able to share with others, to bring joy, to end suffering. And I wanted to do that. And I thought, ‘This is a place where I fit.’ I can be my authentic self here. And just by being my authentic self, I can do this job well. So that involves learning to teach, learning about Zen – I have so much to learn – learning how to do things, learning about pastoral care and how to do one-on-one meetings, learning to do ritual. All of it. I just wanted to do it all. And ordination helped with that.”

“What do Zen teachers teach?” It’s one of my standard questions. A chapter in Further Zen Conversations depicts the range of answers I have received to that question.

“Well,” Ted says, “Zen teachers teach opening up, and that there’s nothing really to be taught and nothing to be learned. And there are not even any words, but it takes a lot of words sometimes to be able to get to that point.” We both chuckle about that for a moment.

“Okay. So you get ordained, you learn how to teach that there’s nothing to be taught, and then eventually you receive transmission from Tim. And it seems that you are looking at it as a ministry. Is that fair?”

“Yeah. I think that’s a good word.”

“Some Soto people go the whole way. They shave their heads and wear Japanese samue when they’re not in robes. They view Soto-style Zen as a denomination with appropriate regalia and so on. Is that the way you see it?” He doesn’t immediately answer the question. “I guess what I’m asking is how strict a Soto Zen Buddhist are you? You’ve got hair, for example.”

“I think I’m in the middle. Of course, a big topic for Zen Buddhists everywhere is how strict to be about the forms and how much to alter them. When I came to Zen Center, things were really quite formal as they had been under Katagiri. Tim Burkett preferred a lot less formality. He thought Americans might respond better if there was less formality, were fewer Japanese forms. I happen to like those forms, so I’ve tried to keep them as much as I can.”

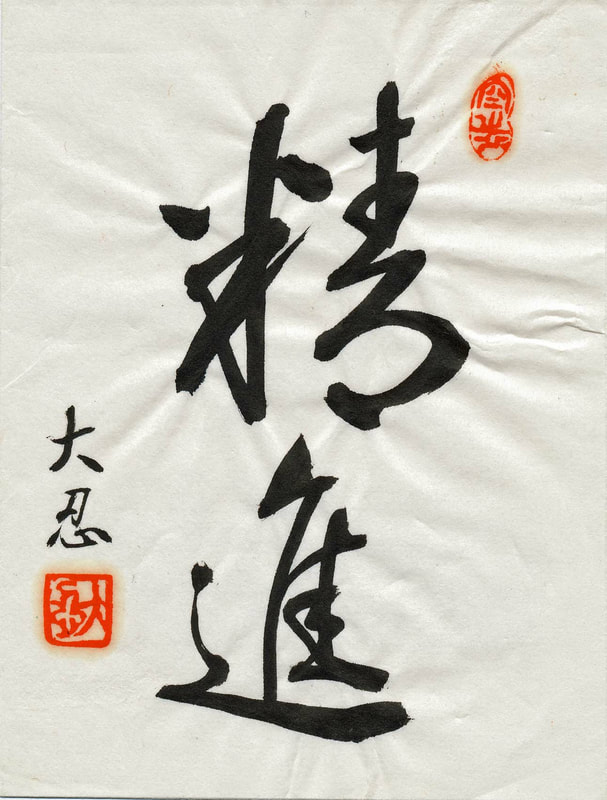

“Do you use a Japanese Dharma name?”

“Sometimes I do. It’s Donen. It was given to me by Shohaku Okumura, and it means ‘Way of Mindfulness.’ I usually don’t use my Japanese name at MZMC. I’ve shaved my head a few times, but ordinarily I have hair. The primary reason I usually have hair is that my wife, Kathy – who is incredibly supportive and has endured much with patience – really likes my hair. I’m not gonna put Zen Center ahead of my wife. If I wreck my home life by being a Zen priest, then everything I’m teaching is kind of a lie. Ordinarily I wear samue and my rakusu when I’m at MZMC, or full robes for daily meditation and formal occasions. I love the ritual. If it were up to me personally, I’d have more of the traditional Japanese forms at MZMC, but, as a community. we have struck a balance which has held for a long time and works for everyone, so I’m not going try to change that now.”

“When new people seek the center out, what are they looking for?”

“Wow, there’s a great variety of reasons why people come to MZMC, why they show up for the first time. One really common reason is I think people are looking for self-help. They want to learn to meditate in order to manage stress. And they come to our intro, which is a four-part series, and we show them how to meditate, and often that’s beneficial. And some folks find out, ‘Oh! This is more than just self-help. This is a spiritual thing. This is like a religion.’ They might not stay, but some do. Some people come because they’re in crisis. They need help – like I did – and they have this intuitive sense that in order to get through the crisis they need to confront life in a very deep way. Some people come as a result of a spiritual quest. Some people see this as a big moment in their life. I’ve heard people say so many times, ‘I’ve walked by this place for ten years, and finally I’ve come in. I think it’s time.’ For some people, walking through the door is one of the biggest steps of their lives. They are ready for something really deep. Which is one reason why I don’t think the forms are so off-putting. People coming here often are ready for something really deep and are ready to embrace new ways of being.”

“What’s the role of sangha in all this?”

“Sometimes it feels like sangha is everything. We really can’t practice on our own. Some people can. You know, some people choose the hermit route, and that’s great. It’s appropriate for some people. But for most people you need the support of others in order to do this practice. This is a very subtle practice. You can forget what it is if you’re not around other people who are doing it. It’s an embodied practice.”

“So it’s not enough to attend an introductory lecture, learn how to meditate and set off on my own?”

“Well, I think you could if you want to do it the hard way. I think you can do that; people can do it in a solitary way. But if what we’re trying to do is open up to the rest of the universe and our interconnections with in it, not thrust ourselves forward but allow ourselves to be part of something else, then sangha is going to teach you a lot. You’re going to go into sangha with your ideas of how things could be. And if you’re like me, and in a leadership position, you’re probably going to make the mistake many times of deciding on some change and then finding out later on that you didn’t take into account all of the effects that that change would have. And then you’re going to learn that, ‘I’ve got to yield to sangha. I have to find out what is needed here and help it to happen rather than imposing my will.’ Everyone needs to learn that. When you become part of a sangha, you are eventually going to come up against something where you realize, ‘Oh, even this sangha, which I’ve idealized, is made up of real people, and I’ve just come across a real person here, and they’re upsetting me a lot.’ And at that point they can decide to work with sangha, or they can leave. And some work with sangha, and they grow as a result, and some go on and try to find a perfect sangha elsewhere. Good luck with that. Sangha teaches you. The best example of interconnections and interrelationships I know is MZMC because it’s such a tight place. If you change one little thing over here, it’s going to affect so many other things.”

“Is there much left there of Katagiri Roshi’s legacy?” I ask. This prompts such a long pause that I remark, “You needed to give that some thought.”

“Yeah, I have to think about that. You know, not having known him, it’s maybe a little harder for me to answer this question. I mean, I really feel his presence even though I never met him. I’ve tried very hard to get to know him by asking questions and things like that. I’ve heard so much about him. He had a real liveliness, I think, that drew people to him. I get the idea that when he was here, the sangha had this great lifeforce which I think is continuing. It’s remarkable how much life there is in this sangha. Sundays we may have fifty people listening the dharma talk in the zendo, and another thirty listening online, twenty in the introductory sessions, and a dozen children upstairs. And it’s joyful. That’s Katagiri’s joy.”

“And now that you are in the teaching seat, what are your hopes for the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center?”

“Well, you know, I would hope that it’s still here in a thousand years.”

“Yeah, it seems to me I heard about some dude way back when who kept going on about impermanence. So that’s unlikely.”

Ted smiles. “Well, perhaps you’ll indulge me on that. I would hope that we would continue to adapt the Japanese forms to our culture, and that we do it slowly and respectfully, and that we never lose the heart of Zen. I don’t care so much if the forms change, but we’ve got to keep the heart of Zen, which is just being here in the moment, now, without fixed ideas. We have got to continue that. And I would like to see – because I have a passion for sangha building – I would like to see us reach more and more people in an effective way. And I have an idea about expanding, about having satellite centers and bringing Zen to more places. It’s starting to pop up in some rural Minnesota towns. Having spent large portions of my life in Iowa, Nebraska, and North Dakota, I know what it’s like to feel a little isolated, and if we can bring the practice to rural areas by sending priests out to them – of course we can do some of this virtually now – I would love to see that. So it’s a challenge of maintaining the practice in its total authenticity and integrity and at the same time expanding it out and providing it to a lot of different people. I think we can do both.”