Abridged from The Third Step East

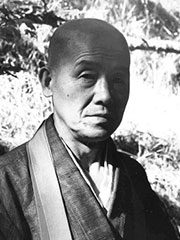

Although Soen Nakagawa spent only brief periods in the United States, he not only helped Robert Aitken establish the Diamond Sangha in Hawaii, he was also the inspiration behind the International Dai Bosatsu Zendo in the Catskill Mountains, the first Rinzai Monastery to be established in North America. He was a complex person, renowned both for his prowess as a Zen master and a poet; people in Japan who had little interest in Zen admired Nakagawa as one of the most accomplished haiku composers of the 20th century.

He was born in 1907 on the island of Formosa (now Taiwan), the eldest of three brothers. His given name was Motoi. His father was a physician attached to the armed forces who died while Motoi was still young. A brother died soon after.

His early training was appropriate for one born in the samurai class, but he proved to be more interested in literary – rather than martial – arts and showed early promise as a poet. In 1923, he and a close friend, Koun Yamada, enrolled at the First Academy, equivalent to High School, in Tokyo. They would both have significant impact upon the development of North American Zen.

In high school, Motoi sought something meaningful to which he could dedicate his life. He found his direction after coming upon a passage by the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer: “In the real world, it is impossible to attain true happiness, final and eternal contentment. For these are visionary flowers in the air; mere fantasies. In truth, they can never be actualized. In fact, they must not be actualized. Why? If such ideals were to be actualized, the search for the real meaning of our existence would cease. If that happened, it would be the spiritual end of our being, and life would seem too foolish to live.”

He began reading books on Zen, which he passed onto Yamada, initiating his friend’s interest in Zen as well. The two attended Tokyo Imperial University; at that time, Motoi resided in a dormitory attached to a Pure Land temple. He studied both classical and religious literature and continued to develop his skill as a poet. His graduation thesis was on the haiku master, Matsuo Basho.

He formed a Zen sitting group at the university, but it was not until after graduation that he determined to become a monk, much to the disappointment of his family who felt he was wasting the education he had received. He took the Precepts at Kogakuji and was given the Buddhist name, Soen. The master at Kogakuji was Keigaku Katsube, and it was under his direction that Nakagawa began his formal Zen training.

Although now ordained, he did not feel at ease in the communal life of the monastery and chose to follow Bassui’s example by going into solitary retreat on Dai Bosatsu Mountain. There he lived an ascetic life, foraging for wild food, practicing zazen, and writing poetry. He published a few poems in a journal dedicated to haiku and, in 1933, released a collection of poems that he had kept in draft form in a small wooden box; he entitled the volume Shigan, or Coffin of Poems. In San Francisco, Nyogen Senzaki’s landlady came across some of Nakagawa’s work in a magazine and showed it to Senzaki. He also admired the haiku and initiated a correspondence with the young poet.

Nakagawa developed a unique personal practice while at Dai Bosatsu. He composed an original mantra – Namu Dai Bosa, “unity with the great Bodhisattva” – which he chanted with fervor for hours. Aware of current global tensions, he dreamed of establishing an International Dai Bosatsu Zendo where people from all nations could come to practice Zen.

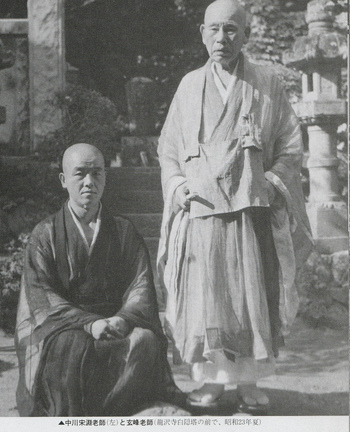

In 1935, Nakagawa served as an attendant to Katsube at a sesshin held for students at the Imperial University. When they arrived, they discovered they had forgotten to bring a kyosaku. Katsube directed Nakagawa to go to a nearby temple, Hakusan Dojo, to borrow one. It happened that sesshin was taking place there as well under the direction of a visiting teacher, Gempo Yamamoto of Myoshinji in Kyoto. Nakagawa arrived while Yamamoto was giving a teisho. Nakagawa had heard many teisho before, but none had touched him as this one did.

Not long after, Nakagawa found another opportunity to hear Yamamoto speak. The roshi quoted Mumon’s commentary on the fourth case in the Mumonkan: “If you want to practice Zen, it must be true practice. When you attain realization, it must be true realization.”

Nakagawa was deeply stirred by the statement and sought a private meeting with Yamamoto wherein he expressed his interest in working with him. It was a serious matter to go from one teacher to another, and, when Yamamoto accepted Nakagawa, Katsube is reported to have called him a thief.

Through their correspondence, Nakagawa and Nyogen Senzaki discovered they shared many opinions, and, although the political situation did not permit Nakagawa to visit Senzaki, they determined that they would meet in spirit. In 1938, Nakagawa wrote to Senzaki proposing that they set aside the 21st day of each month for a shared practice to be known as Spiritual Interrelationship Day. He envisioned a time when people all around the globe with an interest in the Dharma would sit for half an hour in zazen starting at 8:00 p. m. local time, then recite the twenty-fifth chapter of the Lotus Sutra followed by a period of chanting “Namu Dai Bosa.” The evening would culminate with a “joyous gathering.”

During the war years, Nakagawa remained with Yamamoto; however, to the annoyance of many other monks, he persisted in refusing to accommodate himself to the forms of monastic life. Several of them petitioned Yamamoto to expel him. Yamamoto not only refused to do so, he even had a small house built on the temple grounds so Nakagawa’s mother could live near her son.

Once the war was over, Nakagawa was able to travel to San Francisco and meet Senzaki with whom he had been corresponding for fifteen years. He arrived in San Francisco on the 8th of April, the day recognized on the Japanese calendar as the Buddha’s birthday.

He was delighted by the form of Zen practice he found in America, shorn of the stilted formalities of archaic Japanese traditions.

Senzaki had hoped that Nakagawa would remain in the United States and become his heir, but Nakagawa felt obligated to return to Ryutakuji, where he eventually succeeded Yamamoto. Inspired by Senzaki’s example, Nakagawa relaxed many of the formal structures associated with the abbot’s position. He chose not to distinguish himself from other monks, wore the same robes they did, ate with them, and even shared the same bath house. His unconventionality was not admired by the Zen establishment, which saw it as a sign that he had not sufficiently matured into his responsibilities. It was this lack of convention, however, which helped him to play a major role in the spread of the Dharma in North America.

Japanese society tends to be ethnocentric and little accommodation is made for people from other cultures. After the war, soldiers from America as well as from Japan made their way to Ryutakuji looking for a path which would help them deal with the traumas they had suffered. The monastery became known for being accessible to foreign students wanting to learn about Zen. Unconcerned about convention, Nakagawa was not disturbed when students were unfamiliar with the behavioral protocols and matters of etiquette upon which other Zen teachers insisted.

In 1955, Nyogen Senzaki returned to Japan for the first time since his departure fifty years prior. Nakagawa noticed how his friend was aging and was so concerned that he suggested sending his disciple, Tai Shimano, to act as Senzaki’s attendant in Los Angeles. Before Shimano could leave, however, Nakagawa received word that Senzaki had died.

Senzaki had appointed Nakagawa his executor, and Nakagawa went to California to preside at the funeral service. Afterwards, attended by Robert Aitken, he conducted the first formal sesshin to be held in the United States.

Nakagawa’s mother, Kazuko, died in 1962, a year after Gempo Yamamoto’s death. The deaths of Senzaki and then two more people who had played such important roles in his life sent Nakagawa into a depression he struggled to deal with. In 1967, he had a fall on Ryutakuji grounds and lay on the ground, unconscious, for three days before he was found by the monks. He was rushed to hospital, where it was discovered that a sliver of bamboo had pierced his brain. Doctors advised surgery, but he refused it. The fall and his injuries had consequences on his health and personality for the remainder of his life.

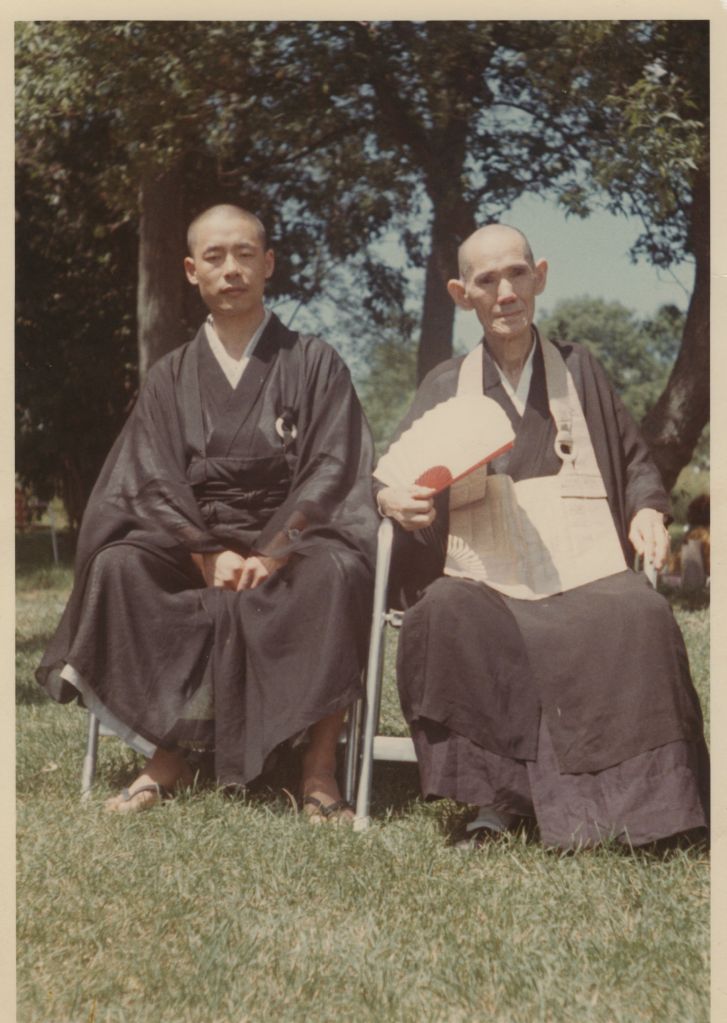

He had a number of disciples in the United States, particularly in New York where Shimano had established the Shoboji Zendo. Nakagawa returned there several times between 1968 and 1971 to lead retreats. During the 1968 visit, he stopped in California to lead a sesshin, after which – accompanied by Tai Shimano and Haku’un Yasutani – he visited Shunryu Suzuki at the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. There Nakagawa scattered a portion of Nyogen Senzaki’s ashes.

In 1973, after having conferred Dharma transmission on Shimano in New York, Nakagawa resigned as abbot of Ryutakuji. He joked that his resignation would now allow him time to act as a midwife to the International Dai Bosatsu Center which Shimano was building. He came back to the US for a while and stayed at the lakeside lodge at Beecher Lake on the Dai Bosatsu grounds. The house was unheated and without electricity, and Nakagawa foraged for wild plants to eat just as he had as a young man on the original Dai Bosatsu. Then he returned to Japan, where he may have expected to be asked to take on various duties at Ryutakuji in his capacity of former abbot; when that invitation did not come, he went into solitary retreat.

According to the autobiographical sketch he wrote for a book published by the Zen Studies Society to coincide with the inauguration of Dai Bosatsu monastery, Tai Shimano’s introduction to Buddhism occurred while he was still a schoolboy during the war. A teacher copied out the words of the Heart Sutra on the blackboard and taught the students to recite them. It was enough to stir his interest. After the war, Shimano entered Empukuji in Chichibu, where his family had moved to escape the bombing raids on Tokyo. The teacher there was Kengan Goto, from whom Shimano received his Buddhist name, Eido; it was derived from the first syllable of the names of the two monks who brought Rinzai and Soto Zen to Japan— Eisai and Dogen. After acquiring the basics of monastic training from Goto, Shimano sought entrance to Heirinji outside Tokyo. As tradition required, he spent two days seated at the gate before gaining admittance.

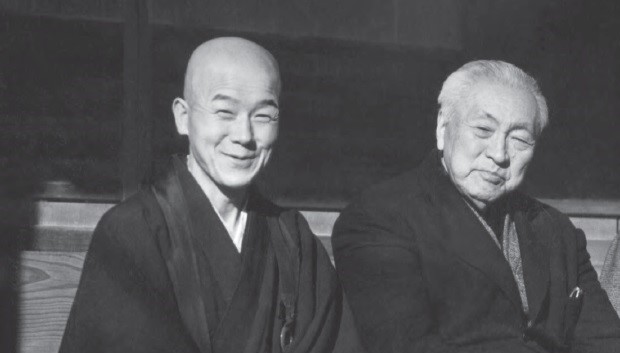

In 1954, Zen Masters and abbots from throughout Japan came to Heirinji to attend the funeral of a former abbot. Shimano was one of the monks assigned to wait on these dignitaries, and, when they first gathered together, he brought them tea. Most accepted their cups without acknowledging the monk serving them. The youngest of the abbots, however, put his hands together in gassho, palm to palm, and bowed his thanks. Surprised to be recognized in this manner, Shimano returned the bow and, later, asked the other servers who the polite master had been. He was informed it was Soen Nakagawa, the recently appointed abbot of Ryutakuji.

Shimano went to Ryutakuji and—after spending another two days waiting at the gate—was accepted as a student.

Shimano proved to be a committed and insightful practitioner, and, over time, master and disciple grew close. Shimano had great respect for Nakagawa and, one summer, made a pilgrimage to Dai Bosatsu Mountain where he located the cottage in which his teacher had stayed.

As he progressed in his training, Shimano was given a number of duties within the monastery. Because of his knowledge of English, he was assigned responsibility for explaining monastery procedures and etiquette to the European and American students who made their way to Ryutakuji. He was known to them by his familiar name, Tai-san. He later wrote that he liked the Westerners he met but recognized that their to approach Zen practice was very different from that of Japanese students. Americans demanded explanations and clarifications and posed questions their Asian counterparts would have considered inappropriate. He also seems to have been attracted to the way in which many of these Western students challenged and flaunted those traditional values and mores which seemed, to them, no longer relevant.

Recognizing Shimano’s ability to interact smoothly with Americans, Nakagawa intended to send him to Los Angeles to act as attendant to the aging Senzaki. When Senzaki died, Nakagawa instead sent him to Hawaii to assist the Aitkens. The Aitkens had met Shimano in Japan and had liked him, so were happy to sponsor his immigration to the US. Shimano arrived at Koko-an in 1958; he was 27 years old.

In 1962, Nakagawa and Haku’un Yasutani were scheduled to lead a number of sesshin in the US. Just prior to departure, however, Nakagawa’s mother fell ill, and he decided to remain with her. He arranged for Shimano to act as Yasutani’s attendant and translator.

The first of these sesshin was held at Koko An in Hawaii, and, even though students needed Shimano’s assistance to communicate with Yasutani during dokusan, five were acknowledged to have achieved some degree of kensho. Shimano accompanied Yasutani on other tours and stated that it was from assisting at these retreats that he learned how to work with students.

Over time, relations between Shimano and the Aitkens became strained. The young, polite, deferential monk they had met in Japan proved to be more problematic in Hawaii. While it was clear he was committed to Zen practice, he also insisted on little extravagances, like a motorcycle which he claimed to need in order to get around. Aitken may not have been happy with these requests, but a case could be made that most of them were reasonable. Then, in 1963, two women from Koko An were hospitalized with mental stress. Their social worker informed Aitken that in both cases they had been in sexual relationships with Shimano.

Aitken, uncertain how to proceed, travelled to Japan to discuss the situation with Nakagawa and Yasutani. Both admitted that it was possible that Shimano had had relationships with the women, but in Japan such matters do not carry the same weight as in North America as long as they are handled with discretion. It would not be the last time that Japanese and North American sexual mores would come into conflict.

Aitken was unhappy with the situation but – heeding legal advice he was given – decided to deal with it quietly in order to protect the still nascent Zen community. The day after Aitken returned from Japan, Shimano left Hawaii for New York. Later he would disingenuously tell Nakagawa that he left because “the Hawaiian climate is too good—it is a place for vacationers or retired people, but not for Zazen practice.”

Shimano arrived in New York on the last day of 1964. He was newly married to a Japanese woman who apparently granted him the latitude many Japanese husbands had as far as extra-marital relations were concerned. The following day—the first day of the New Year—he began his new life on the North American continent as a Zen teacher. Later, he would suggest that he attracted his first students by sheer force of personality just walking the streets of Manhattan in his Buddhist robes. In fact, however, a number of New York students who had attended Yasutani’s sesshins provided him a base in the city. Although he had not yet received full transmission, he demonstrated skill as an insightful and inspiring teacher. He could be charming and was a sensitive and supportive friend. He could also turn stern and forceful if needed, showing little patience with half-hearted efforts in the zendo.

The New York Zendo, as it was called, originally met in the living room of Shimano’s small apartment. There were, as yet, no membership fees, and Shimano earned a small income by going through the Manhattan telephone directory culling Japanese names for a mailing list being compiled by the Bank of Tokyo.

As the number of students increased, programs and activities grew. At first there were only regular sittings at the apartment; then day-long sits were added and even weekend sesshin. When the living room zendo was no longer adequate, the sangha discussed ways in which to raise funds to purchase or rent a larger space. In order to do so, they needed to incorporate as a religious organization and acquire tax-exempt status. The expense associated with that process, however, was beyond their means. According to Shimano’s account, it was for that reason that they approached the Zen Studies Society which had been established in the city some years prior to promote the work of D. T. Suzuki. The society was currently inactive and owned no property although it still existed as a legal entity. It was not in a position to assume responsibility for Shimano’s immigration status, but the secretary of the society, George Yamaoka, assisted Shimano to become a board member, and the Society quietly merged with the New York Zendo. When Suzuki – then living in Japan – learned of the arrangement, he requested that his name be deleted from the Society’s letterhead.

After the merger, fund-raising began in earnest, aided by a generous initial contribution of $10,000 from a Canadian student who was returning to home. Soon the group was able to move into new quarters on 81st Street, where Yasutani led their first sesshin in the summer of 1965. There was a growing interest in Zen practice throughout America, a surge never equaled since, and, before long, people were turned away from the zendo because there was not sufficient room for them.

A number of serendipitous events occurred during this period. On a visit to San Francisco, Shimano happened upon an antique shop where he found a large keisu—a bowl-shaped gong—which had been forged in 1555 for Daitokuji in Kyoto. In another antique shop, in New York City, he found a seated Buddha figure which had originally been made for a branch temple of Enpukuji, where he had begun his own training. Although the zendo was still strapped for cash, money was found to purchase these treasures. Then, in 1968, Chester Carlson—founder of Xerox—donated funds for them to move to more suitable quarters in a former carriage house on East 67th Street. Carlson’s wife, Dorris, was interested in Eastern Spiritualities, and, through her intervention, Carlson anonymously assisted both Shimano and Philip Kapleau in establishing their communities.

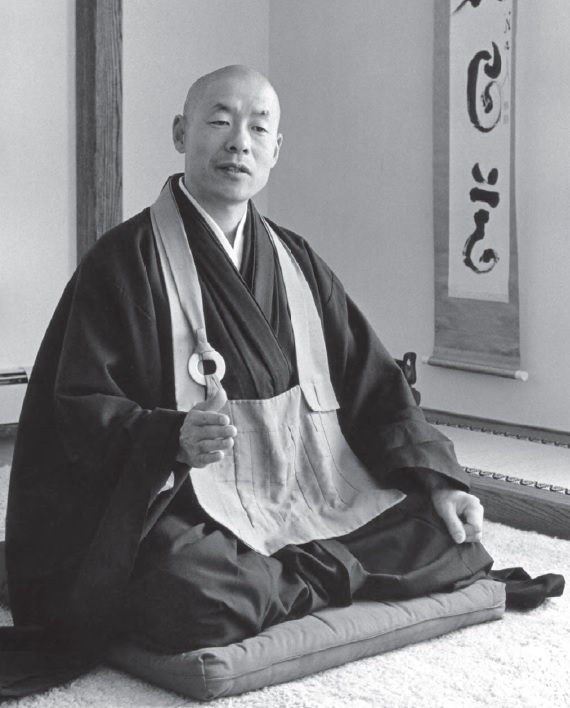

That summer Yasutani and Nakagawa were in California to conduct sesshin there, and Shimano joined them. Afterwards, in New York, Nakagawa presided at the ceremony officially inaugurating the New York Zendo Shobo Ji (Temple of True Dharma). He was declared the zendo’s abbot, and Shimano was the teacher-in-residence.

The pioneers who brought Zen to North America were familiar with two models from Japan: the temple and the monastery. Temples served the devotional needs of local communities, as Sokoji served its Japanese congregation in San Francisco. Monasteries had several functions; they were facilities where temple priests were trained, but they were also increasingly—especially, in the Rinzai tradition—centers for the spiritual development of both ordained and lay practitioners. Practice centers, such as Shobo Ji, were a distinctly Western phenomenon. Despite its title, Shobo Ji was not a temple in the usual sense of the term; nor was it a training center. During his visit to California, Shimano had been particularly struck by Tassajara – a remote training center dedicated to practice and formation.

No sooner had Shobo Ji been opened than Shimano and his board began to consider opening an American Rinzai temple and training center with a residential program where traditional Buddhist devotional and training activities could take place. Its primary function would be to serve as a dedicated site for sesshin. Currently, even with Shobo Ji, it was necessary to rent facilities with adequate accommodations for sesshin participants. The necessary physical apparatus – zabutons, zafus, keisus, mokugyos, and so forth – had to be transported to and from the rented site; rooms needed to be rearranged to serve as the zendo and the dokusan chamber.

Shimano envisioned an actual temple, and, because Zen temples in Asia were usually in the mountains, he hoped to find a suitable mountain setting. A Building Committee was established which explored a number of potential sites, each of which proved inappropriate. Then the chair of the committee chanced upon an ad in the New York Times for 1400 acres in the Catskill Mountains. The property had belonged to the family of Harriet Beecher Stowe; the small lake was known as Beecher Lake. There was a handsome fourteen room summer house – referred to as a “lodge” – located there, remote from all other habitations. It was an ideal spot, but the cost was would have been prohibitively expensive had it not been for another generous donation from Dorris Carlson.

Nakagawa came to New York that summer, and Shimano took him to the site. The older man was entranced. As they walked about the property and along the shore of the lake, Nakagawa told his disciple of his youthful hope of establishing an International Zendo on Mount Dai Bosatsu. Shimano suggested that this new site, in what Nakagawa liked to call the Cut-kill Mountains, be named the Dai Bosatsu Zendo. Nakagawa’s dream would become a reality, not in Japan but in America.

The first sesshin was held in the lodge. A small tent – just large enough for two people to sit face-to-face – was set up to serve as the dokusan room. The New York community energized by the sesshin and its location took on the construction project with enthusiasm. A local architect, Davis Hamerstrom, was hired and traveled to Japan with Shimano to study temple architecture. They visited a number of temples before coming to Tofukuji, the largest Rinzai temple in the country and a designated National Treasure. They were struck by the resemblance of its setting to the Beecher Lake site. The abbot, Ekyo Hayashi, opened a presently unused building where, at one time, as many as a thousand monks had practiced. Hamerstrom and Shimano had found the model they had been seeking.

In September 1972, Nakagawa formally gave Shimano transmission, making him abbot of both Dai Bosatsu and Shobo Ji. Following the installation, there was a “Mountain Opening” ceremony, dedicating the site to the construction of the proposed temple, and Nakagawa was declared Honorary Founder. A final portion of Nyogen Senzaki’s ashes were interred at the site.

The following spring, work began on what was, arguably, the most significant Zen construction project to be undertaken in America. Deep in the mountains, approached by a narrow county road and then another two miles of gravel road from the formal entrance gate, a Japanese-style temple of classic design was built.

Its full formal name is Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo Ji (Diamond Temple), and it was officially inaugurated on America’s bi-centennial – July 4, 1976. Rinzai dignitaries from Japan came for the occasion; teachers from throughout America were there, including Robert Aitken, Richard Baker, Taizan Maezumi, Philip Kapleau, the Tibetan teacher, Chogyam Trungpa, and the Korean Zen Master, Seung Sahn. American writer, naturalist, and Zen practitioner, Peter Mattiessen, struck the large temple bell beginning the ceremony.

The person conspicuous by his absence was Soen Nakagawa.

After Nakagawa returned to Japan in 1973, he still suffered a great deal of physical pain and sought solace in saki rather than in western medicines, which he distrusted. The drinking only made him more morose. In retrospect, his students would come to realize that he was suffering from depression; he hid his condition so well, however, that his few visitors failed to see the signs. He was always able to feign a pleasant and even merry facade when necessary.

He became increasingly withdrawn with the passing years, remaining in his quarters at Ryutakuji without interacting with the other monks. He allowed his hair and beard to grow. He stopped writing poetry. His relationship with Shimano had ruptured when he learned that Shimano was still involved in serial sexual relationships with his female students. The loss of that friendship added to his unhappiness.

In 1975, he was invited to take part in a ceremony at the prestigious Myoshinji in Kyoto, the primary Rinzai temple in Japan. The ceremony would have made Nakagawa acting abbot for a day, an honor which usually led to permanent appointment. In the history of the temple, Nakagawa was the only individual to turn down this opportunity. He said that, instead, he was preparing to take on the position of abbot at Dai Bosatsu in America. As the date neared for those opening ceremonies, however, Nakagawa put off his departure and, in the end, did not attend.

An American Zen student, Genjo Marinello, happened to be studying at Ryutakuji in 1980, and although he knew Nakagawa was on the grounds, he suspected he would spend his entire time in Japan without having an opportunity to meet him.

“During teisho at sesshin at Ryutakuji,” Genjo told me, “because my Japanese wasn’t so fluent, I would go to a little side room during the teisho time and listen to cassette tapes of Soen Roshi. So I’m sitting in zazen, and I’m listening to a cassette tape of Soen Roshi, and he’s so eloquent, and he’s so sweet, and he’s so poetic, and it’s such a treasure, I just felt honored to be listening to him. I knew that he was only feet away from me, from where I was listening, but he was such a recluse, I thought I might be in Japan the whole time and never see him. But I’m sitting in this little anteroom, sitting in zazen and listening to his teisho, and in walks this guy in a white, grubby kimono, somewhat in tatters. Long scraggly white hair and a long white beard. And he sees me, a young American in formal Zen robes listening to a teisho of his. And he had raided the kitchen. That’s what he was doing, was raiding the kitchen and hoping no one would see him because it was teisho time so he didn’t expect to see me there. If he’s startled, he doesn’t look startled. He’s a roshi. So he sees me, and my jaw drops open. Of course, I know who I’m looking at. It’s not a mystery. And then he says, ‘Gassho!’ So I put my hands in gassho, and he walks on by. That was our first encounter.”

After that meeting, Nakagawa frequently asked Marinello to take walks with him around the temple grounds. He shaved his head again, took better care of his appearance, left the hermitage, occasionally sat in the zendo, and once again joined the monks at mealtimes. He also made numerous long distance phone calls much, Marinello remembers, to the abbot’s annoyance.

Nakagawa made a final visit to the United States in 1982 and, in his last teisho to his American students, said: “There are so many pleasures in life! Cooking, eating, sleeping, every deed of everyday life is nothing else but This Great Matter. Realize this! So we extend tender care with a worshipping heart even to such beings as beasts and birds, but not only to beasts, not only to birds, but to insects, too, okay? Even to grass, to one blade of grass, even to dust, to one speck of dust. Sometimes I bow to the dust.”

Two years later he died at Ryutakuji.

Soen Nakagawa’s ashes were divided into three parts. One third was returned to the Nakagawa family; one third was buried with those of the former abbots of Ryutakji; and one third was buried along with Nyogen Senzaki’s at Dai Bosatsu, where a stupa commemorates both men.

Many of Eido Shimano’s students respected him as an effective and inspiring teacher, and, for some, that alone mattered; for others, his personal life eventually became an embarrassment and impediment to continue working with him.

Aitken had remained silent about what he knew of Shimano’s early sexual improprieties, perhaps hoping the young man would mature out of such behavior. As time passed, however, further stories emerged. The inauguration at Dai Bosatsu was the last time Aitken and Shimano were together. Afterwards, Aitken refused to attend conferences if he knew Shimano would be attending and—according to Buddhist scholar Helen Baroni—he advised other Zen teachers to do so as well.

Shortly before his death, Aitken turned over his personal papers to the University of Hawaii. Included in them were his records regarding Shimano. The release of those papers were part of a series of events which eventually forced Shimano to resign his position as abbot of Dai Bosatsu.

Within a decade of the inauguration of Dai Bosatsu, several of the most prestigious Zen Centers in America would be burdened by issues of teacher misconduct and the discrepancy between enlightened perception and unenlightened behavior.

5 thoughts on “Soen Nakagawa and Eido Shimano”