Adapted in part from The Story of Zen–

The history of the transition of Zen to the West is a tapestry of concepts, personalities, and events. One of the most distinctive elements is the story of a Japanese-trained Englishwoman who appeared in San Francisco in 1969.

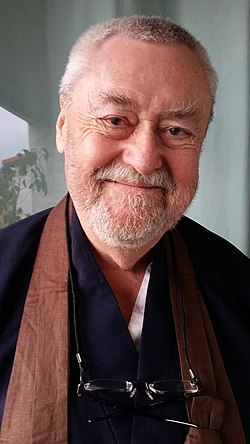

“I’ve been trying to reconstruct Jiyu Kennett Roshi’s history,” James Ford told me during the first of our several conversations. “There’s this whole hagiography machine around her at Shasta. There’s what I knew, and then there’s what I learned from secondary sources since. It’s still pretty much my belief that she had a mandate to do something in London, and she had swung by San Francisco in 1969 because it was the first successful outreach to the gaijin. And you can say many things about Jiyu Kennett – some really good – and among those was, she was real smart. And she arrives in San Francisco. She thinks about London. She decides she’s going to put her business up in California. And she moved into a flat on Potrero Hill, and now she was receiving, and I was her first student. Now there is another fellow who claims he was her first student, but he arrived there on a Thursday, and I was there on a Wednesday.

“So I started sitting with her. I mean I had an actual teacher right there I could see every day, and I would spend all my time there. But then her parents had both died while she was in Japan, and she had an estate; not much of one, but there was something to wind up, and she had to go back to London. She brought two students with her, and I was invited to move into the flat on Potrero Hill and pay the rent. With the proviso that I marry my girlfriend. So we got married. And it caused sadness for both of us.” The marriage didn’t last, and James still feels resentment about being forced into it.

“But we moved in. And – you know – I was a residential practitioner from that point on. After Kennett Roshi had been in England – I forget, a couple of months? – she sends a note saying she’s bringing sixteen people. We better move. So we acquired a very large house in Oakland, and I ordained in Oakland. Unsui. Then it really went fast. Acquired the property on Mount Shasta within the year, and I received transmission up in Mount Shasta.”

“How old were you?”

“Twenty . . . I can’t remember now. Twenty-one or twenty-two. Yeah. A child.”

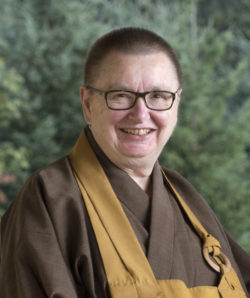

Gyokuko Carlson also received transmission from Kennett in the ’70s. “Roshi Kennett transmitted extremely early,” she tells me. “It boggles my mind how quickly she transmitted people.”

“And this gave you the authority to teach?” I ask.

“Which is why it’s staggering that it came on so early. I think it might be influenced by the fact that she was transmitted so early herself, that that early transmission felt kind of normal to her.”

“How old were you?”

“When I got transmission? I’d only been ordained two years.” She calculates the dates in her mind. “Uh . . . 1977 . . .”

“That would have made you 28.”

“Yeah,” she says, echoing James. “A child.” Then a little later, she adds, “You know, when I was ordained by Roshi Kennett, she didn’t know me.”

“Did you think of her as your personal teacher?” I ask.

“What I identified as my teacher was the abbey itself and the schedule. There was a novice master, and I was allowed to talk to him about questions I had. He was a little bit imperious and not super-approachable. You could sneak questions to other seniors as needed, but I almost never had any kind of conversation with Roshi herself. She gave lectures. She would attend teas sometimes. But she was kind of off in the distance. Before I was ordained, a couple of times, she would address me by some other monk’s name. You know, ‘round face girl.’ There are a bunch of them; they can all go by one name.”

I ask her what she meant by saying the abbey and the schedule had been her teacher.

“Well, I felt that I was being immersed and disciplined into a way of life that was structuring my mind. We sometimes say about the meditation posture is that you’re using your body to direct the mind. And I felt that everything in the schedule and the method of being, the deportment, it was all there to direct the mind.”

Peggy Kennett had been born in Britain in 1924 and studied medieval ecclesiastical music at Trinity College. For several years, she was a church organist and admitted later in life that she’d felt drawn to the priesthood; unfortunately, that wasn’t yet an option for women in the Anglican Church. That discrimination caused her to question gender roles both within the church and in society in general. It also provoked a growing dissatisfaction with Christianity as it was currently practiced.

Her father had belonged to Christmas Humphrey’s London Buddhist Society when it was still associated with the Theosophical movement. Kennett joined as well in 1954 and began a correspondence course on Theravada Buddhism through the Young Men’s Buddhist Association in Ceylon. Her interest in Zen began when she met D. T. Suzuki during one of his visits to London. Then, in 1960 the Society asked her to organize the visit of a Soto priest, Keido Chisan Koho. He was pleased with her work on his behalf and invited her to come back with him to Japan. She agreed although it took another two years before she was able to join him at the prestigious Sojiji Temple in Yokohama.

Peggy didn’t have an easy time at Sojiji. There hadn’t been a female student there since the 14th century. More traditional members of the community resented her presence not only as a woman but as a foreigner, and they made her stay difficult. With Chisan Koho’s support, however, she persisted and even achieved kensho. In her biography, she said it came about in part because of the frustration she felt with the way she was being treated. Once she let her sense of self drop, she achieved awakening and felt only gratitude for those who had tormented her.

Chisan Koho gave her Dharma transmission in 1963, and for a period she served as abbess of Unpukuji in Mie Prefecture where she worked with non-Japanese students. Koho expected that she would return to England and sent a letter to the Buddhist Society informing them that Kennett was to be the Soto bishop of London. Humphreys was surprised and wrote back, tactlessly, that they would prefer a “real Zen master.” Koho was angered at having his authority questioned and ordered his secretary to “write to this man in England and tell him he obviously understands nothing whatsoever about true Zen.” Humphries didn’t appreciate the tone of the letter, and Kennett was no longer welcome in the London Buddhist Society.

She left Japan after Koho’s death in 1967. Her health wasn’t strong at the time, and the animosity of the conservative Soto community continued. She may have hoped to establish a teaching center in England regardless of the Buddhist Society, but as it happened she undertook a lecture tour in the United States which gave her an opportunity to visit the San Francisco Zen Center in 1969. Impressed by what she saw there, she was inspired to remain in the city. She found an apartment in the Potrero Hill district and began receiving students. Within a year, she and a number of disciples she’d gathered – including James Ford – moved three hundred miles north of the city to the township of Mount Shasta.

Shasta Abbey – as her community became known – could house fifty monks, a term indiscriminately used for both males and females. At times Kennett referred to the members as “he-monks” and “she-monks.” Her experience both with the Anglican Church and in Japan made her determined to ensure that men and women were equally respected in the community. The writer Sandy Boucher noted in her book, Turning the Wheel: American Women Creating the New Buddhism, that in her personal experience – not just as a Buddhist but as an American woman – her visit to Shasta Abbey was the first time she felt she was “in an environment where women were equally visible and equally responsible with men.”

Kennett fell seriously ill in 1975. She consulted a traditional Asian healer who diagnosed that her condition was due to stress. He warned that she would be dead within three years if she didn’t change her lifestyle. So in 1976, she took leave of her position as abbess and went into solitary retreat. Over the next nine months, she claimed to have meditated both on her present and past lives and as a result had a series of forty-three visions comprised of both Christian and Buddhist elements.

It isn’t unusual for people engaged in prolonged meditation to have visions. The Japanese term for these is “makyo,” which essentially means hallucination, and they aren’t generally considered to be more significant than dreams. Kennett, however, considered her visions a form of kensho and believed they were genuine revelations. The fact that she overcame her illness – and lived for almost another twenty years – was, to her mind, evidence of their validity.

In some ways – as the content of the visions demonstrated – Jiyu Kennett never wholly abandoned her emotional ties with the Anglican church. She claimed that Chisan Koho had told her to develop Western forms for Zen practice in order to make it more accessible to Americans and Europeans. Taizan Maezumi had said something similar to his heirs. The controversy with Kennett was the way in which she chose to carry those instructions out. In the early days, the clerics of her order wore Roman collars, were addressed as “Reverend,” and resided in “abbeys” or “priories.” The chants were translations of traditional Soto texts but were sung in Gregorian plainsong with organ accompaniment.

Unlike many Soto teachers, Kennett insisted on the importance of kensho, maintaining that it was fairly easily attained through committed zazen practice provided the student remained focused on the “intuitive understanding which the teacher is always exhibiting.” Stephen Batchelor, writing about Kennett, explained:

“All theories, ideas, concepts and beliefs have to be discarded. In their place one ‘must have absolute faith in the Buddhanature of the teacher.’ Therefore, she concludes, ‘Zen is an intuitive RELIGION and not a philosophy or way of life.’ She deplores how for centuries Buddhism has been denied as a religion: ‘this was because [people] feared saying the Truth lest they set up a god to be worshipped. The Lord is not a god and He is not not a god.’”

Although the initial kensho experience, according to Kennett, was equally accessible to lay and monastic, if one wanted “to go further than that” a deeper commitment was required which was – she later insisted – not consistent with an active sex life. So, in spite of having compelled James Ford to marry earlier, she now asserted, “If you’re married, the singleness of mind, the devotion, the oneness with [the] eternal can’t take place, because you’re dividing it off for a member of the opposite sex or a member of the same sex, or whatever.”

Gyukuko met her future husband, Kyogen, while at Shasta.

“We formed an attachment that roshi was informed about, and she first said, ‘Oh, great. You two are so perfectly suited.’ Later she decided, ‘No. We’re going to be all celibate. You can’t do that.’ She would run hot and cold with us for three years. But the rule at that time was that if you were forming an attachment and wanted to pursue it, you had to leave the abbey for at least three months to get over the hot and heavy part of it. And then you could come back and live separately after that. Well in one of these hot and cold periods with roshi, she told Kyogen, ‘If you want to marry that girl you have to understand you’ll never be abbot of Shasta.’ And he said, ‘I don’t want to be abbot of Shasta.’ I can’t imagine her being speechless, but she didn’t have much of a response to that.”

“I understood that early in her career she, in fact, encouraged students to marry,” I mention. “In at least one case I know of even pressured couples to do so.”

“Yeah. Shuyu and Gyozan Singer, for example, were married by her and ordained at the same time. So, yeah, she was for it. And early in her career she wrote an article saying that any time there is an effort at control from one institution over the small branches of the institution, then religion flies out the window. So she was backtracking on a lot of her original teachings.”

Most Soto priests in Japan are married.

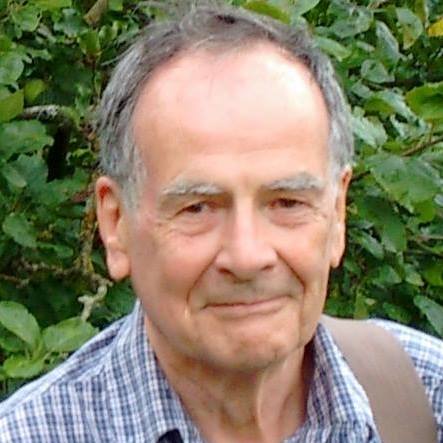

James was the second person to receive transmission from Kennett, the first was Mark Strathern, one of the Englishmen who came to the United States with Kennett after her visit to Britain. Like James, he too eventually left Shasta. In an on-line personal reflection,[1] Strathern points out that when he was first with her, “What Jiyu taught was a very orthodox Soto with some minor adaptations to western needs. She was a powerful and authoritarian figure but had a few personal foibles, a minor paranoia about English and Japanese authorities persecution amongst them. But nothing that got too much in the way of our training which followed the lines of her own training in Sojiji.”

When his visitor’s visa expired, Strathern returned to England, where he eventually founded, with Kennett’s guidance and authorization, Throssel Hole Buddhist Abbey. During a return visit to the US, Strathern noted that in his absence Kennett had become “more erratic and autocratic.” She and some of her disciples now claimed to have been able to experience former lives.

“I did not see the relevance of this to Soto Zen, or any Zen for that matter,” Strathern writes. “But, whatever, who was I to know so I threw myself back into things and took the advice I had given to others on a number of occasions – that is to set a time limit at some point in the future and to suspend disbelief and judgement till then and see how I felt at that later time. However as time went on the experiences became more and more outlandish. I believe it was Eko[2] who had been Jesus, others including Jiyu had been, Bodhidharma, St John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila, and any number of inmates and guards from German World War II concentration camps. My touchstone at the time was, ‘Does this lead to the truth?’ and this sure wasn’t leading me on the path to the truth; it was blocking it.”

As her methods and perspective moved further from traditional models, Soto authorities in Japan became less at ease with her and eventually chose not to acknowledge her order or the validity of the transmissions she authorized.

Regardless, she left a legacy. She died in 1996 at the age of 72, but Shasta Abbey continues. As does Throssel Hole Abbey. Although so does the controversy.

“Some years ago,” James tells me, “a former inmate of Shasta Abbey who, when he left, went on to become filthy rich in the computer industry, offered a retreat, a little gathering in Portland for anybody who had received Dharma transmission from Jiyu Kennett and had left. And if you could get to Portland, he’d put you up in a hotel, and there were meetings. It was kind of a lovely event. I still have the ragged remains of a t-shirt which said, ‘I spent blank years at Shasta Abbey and all I got was this lousy t-shirt.’ The other thing I still have, there was a portrait of Jiyu Kennett, some official photograph, cut up and turned into a jigsaw puzzle.”

James fell away from Zen practice for a while after leaving Shasta, then resumed study with John Tarrant from whom he received transmission in 2005. He is now at the head of one of the most significant Zen lineages in North America. Gyokuko and Kyogen Carlson became the founders of the still vibrant Dharma Rain Zen Center in Portland, Oregon. And both James’ and the Carlsons’ heirs can claim affiliation with the Soto lineage through Jiyu Kennett.

[1] http://obcconnect.forumotion.net/t134-my-experience-and-leaving-mark-daiji-strathern

[2] Eko Little was Kennett’s assistant for many years and succeeded her as abbot. He was later asked by the Shasta Board to resign his position because of matters of personal conduct and he returned to lay life.

Sad story

LikeLike