Adapted from The Third Step East –

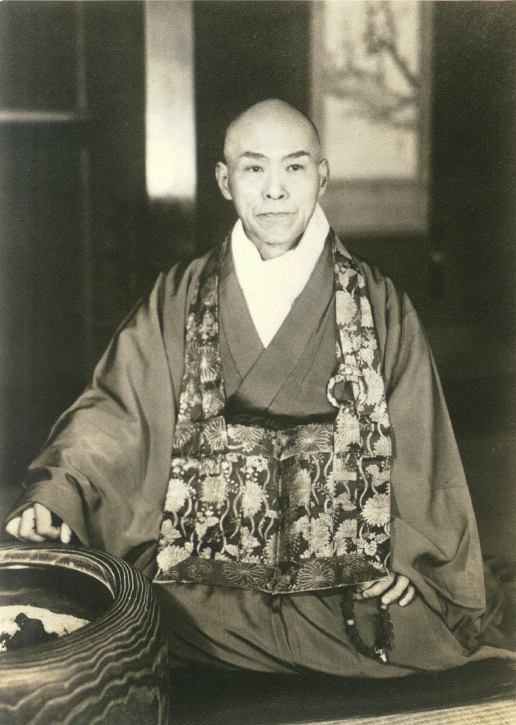

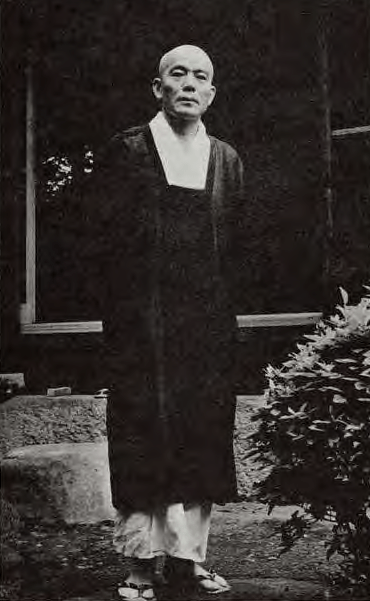

D. T. Suzuki was a scholar. Nyogen Senzaki was an effective teacher, but he had not been formally authorized as one. The first fully authorized, or transmitted, Zen Master to teach in North America was Sokei-an Sasaki.

He was the son of a Shinto priest who died when the boy was 15 years old. There was some expectation that he would follow his father’s career, but his natural inclination was to art, and his mother’s family arranged for him to be apprenticed to a sculptor at the Imperial Academy in Tokyo where he learned traditional Japanese woodwork and specialized in carving dragons.

As he matured, he found himself reflecting on issues which had troubled him since childhood. He later wrote: “At seventeen or eighteen, we open a doubtful eye: Why do we live? Where do we come from? Were we here before? Where do we go? If we have no such period of seeking, I should say that we are sleeping. This questioning comes to every young man’s eye.”

These concerns remained with him as he pursued his art studies. He learned samadhi – meditative absorption – not in a monastery but from an art teacher who instructed his students when they sought to paint the sea “not to sketch the waves on the seashore or to copy the waves in the ancient masterpieces. ‘Without brush or palette,’ he said, ‘go alone to the seashore and sit down on the sands. Then practice this: forget yourself until even your own existence is forgotten and you are entirely absorbed in the motion of the waves.’”

There were, Sasaki would discover, many kinds of samadhi, and Zen itself – as he put it – was an art form. “I found this knack of going back to the bosom of nature because I was an artist and worshipped Nature. From this feeling, I entered Zen very quickly.”

One day he set up his easel to paint but found himself stymied, unable to draw a line. He understood that it was time to put away his canvas and palette and seek a Zen teacher. The master he approached was one of Soyen Shaku’s disciples, Sokatsu Shaku.

Soyen Shaku had assigned Sokatsu responsibility for overseeing Ryomokyokai – the Institute for the Abandonment of Concepts – which Imakita Kosen had established in order to foster the practice of Zen among lay persons. An old farm house outside of Tokyo, surrounded by rice fields, had been converted into a temple. There were two buildings in the temple enclosure. One was the teacher’s residence, the other served as the zendo. Here Soyen Shaku and Sokatsu carried on Imakita’s hope of revitalizing the Zen tradition by working with well-educated and culturally talented lay practitioners.

Sasaki was nineteen years old when he presented himself at the temple and asked to be accepted as a student. Sokatsu asked him, “What career do you follow?”

“I’m a sculptor,” Sasaki replied.

“And for how long have you practiced this craft?”

“Six years.”

“Very well. Carve me a Buddha.”

Sasaki returned to his studio and began work on a carving which, when completed, he brought back to Ryomokyokai and presented to Sokatsu. The Zen master took the statue and demanded, “What is this?” Then he tossed it into a nearby pond.

In that way, Sasaki’s Zen training began.

He was given the Buddhist name Shigetsu (Finger Pointing to the Moon) but remained a layman. He was still enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts and earned a modest living travelling about Japan repairing old temple carvings. After graduation, he was drafted to serve in the Russo-Japanese War and was sent to Manchuria, where he drove a dynamite wagon. The experience made him all the more aware of the precariousness of human life.

The war ended two months later, and, once discharged, Sasaki returned to Tokyo to continue his studies with Sokatsu.

Encouraged by Soyen Shaku, Sokatsu planned to take a small group of disciples to America in order to establish a Zen community there. He invited Sasaki to join them but insisted that he would need to be married if he chose to participate. So a marriage was arranged with another lay student at Ryomokyokai, a woman named Tomeko who was a student at Japan’s only college for women.

In September of 1906, Sokatsu and six disciples left for California where they purchased a ten-acre farm in Hayward. None of the Japanese had any agricultural experience, and the land was poor and exhausted. The enterprise failed after a single crop of strawberries was harvested. Sasaki and Tomeko left the farm to go to San Francisco where he enrolled at the California Institute of Art. While in San Francisco he met and was befriended by Nyogen Senzaki. The two would remain in contact throughout their lives though they did not always see eye to eye.

Sokatsu and the other disciples were unable to maintain the farm and eventually also moved to San Francisco where they established an American Branch of Ryomokyokai. At its height, it had about fifty members, most of whom were Japanese. Eventually, Sokatsu returned to Japan, and all of his disciples, save for Sasaki and Tomeko, went with him.

Sasaki then began to explore the United States. For a while, he was able to find work in California repairing statues for an importer of Asian sculpture. Then he hiked north to Oregon where he was able to make use of his wartime experience by dynamiting tree stumps for a farmer. He also worked as a janitor in a bar and for a time as a professional dance partner at a roller rink. In the evenings, he sat in meditation on a rock by the river with a dog to protect him from snakes.

Eventually he and Tomeko came to Seattle where he worked as a picture framer. He could not afford the studio and tools necessary for carving, so took up writing and began a series of humorous reflections on American life for Japanese periodicals.

Sasaki and his wife lived in humble circumstances. For a while, they stayed with the Salish people on an island in the Puget Sound. The Japanese couple had faced a great deal of prejudice elsewhere in America, and Tomeko felt more at ease with the Native Americans than she had anywhere else. By this time, they had two young children, and when, in 1914, Tomeko became pregnant a third time, she informed Sasaki that she wanted her children to be raised in Japan. She left him and went to live with her mother-in-law who was aging and had written to ask her daughter-in-law to come care for her.

Unencumbered by family obligations, Sasaki wandered about the United States for the next two years, arriving in New York City in 1916, at the age of 34, where he naturally gravitated to Greenwich Village.

Sasaki was fascinated with the wide variety of lifestyles he came across during his travels, ranging from the conservative values of small-town America to the sophisticated charlatanism of the Bohemian community he fell in with in the Village. There he encountered people like Aleister Crowley, the British occultist and self-proclaimed mystic. The essays Sasaki sent back to Japan about the people he met and the events he encountered were popular, and he began to acquire a literary reputation. He also wrote in English, making translations of classic Chinese Poetry.

He was welcomed into the artistic milieu of the Village and led a comfortable life, but he still had not resolved the issues which had originally drawn him to Buddhism. Then on a hot and humid day in July 1919, he came upon the putrefying carcass of a horse lying in the street. The sight struck him so strongly that he immediately made arrangements to return to Japan.

He resumed his study with Sokatsu and even tried reconciling with Tomeko but remained restless and soon returned to the US. For several years, he travelled back and forth by steamship between Japan and America, studying Zen with Sokatsu at Ryomokyokai and working as an art restorer in New York. Eventually, during one of his return trips to Japan, he realized that if he were serious about his Zen practice, he needed to commit to it until he achieved full awakening.

Sokatsu assigned Sasaki the koan which demands, “Show me your original face, your face before your parents were born.” Sasaki had been reading German philosophy and, for a while during his sanzen meetings with Sokatsu, tried to reply to the koan in the light of his understanding of those writers. Often, however, he barely began to speak before Sokatsu rang the bell dismissing him. Finally Sokatsu bellowed at him, “Before father and mother there were no words! Show me your face before their births without words!”

Sasaki struggled for years before resolving the koan. Then, one day: “I wiped out all the notions from my mind. I gave up all desire. I discarded all the words with which I thought and stayed in quietude. I felt a little queer, as if I were being carried into something, or as if I were touching some power unknown to me. I had been near it before; I had experienced it several times, but each time I had shaken my head and run away from it. This time I decided not to run, and Ztt! I entered. I lost the boundary of my physical body. I had my skin, of course, but I felt I was standing in the center of the cosmos. I spoke, but my words had lost their meaning. I saw people coming towards me, but all were the same man. All were myself! I had never known this world. I had believed that I was created, but now I must change my opinion: I was never created; I was the cosmos; no individual Mr. Sasaki existed.”

When Sasaki next met with Sokatsu in sanzen, the teacher immediately recognized that his student had had a breakthrough. “Tell me about this new experience of yours,” he demanded.

Sasaki looked at him without speaking. Sokatsu smiled.

Sasaki was 47 years old when he completed his training and received inka – authorization to teach – from Sokatsu. To mark the occasion, Sokatsu also gave him the name Sokei-an. Sokatsu encouraged him to return to the United States, telling him that interest in Zen was diminishing in Japan; the tradition needed to be carried to North America if it were to survive. He instructed his student to be diligent in familiarizing himself with the people and culture of the United States because it would now be his responsibility to ensure that Buddhism was successfully transplanted there. Because of his reservations about the Zen hierarchies in Japan, Sokatsu wanted Sokei-an to remain a lay teacher. Sokei-an, however, felt that he would have more credibility in America if he were ordained. When Sokatsu refused to carry out the ordination, Sokei-an went to another priest who was willing to perform the ceremony. Sokatsu considered this a betrayal and the two remained estranged for the remainder of their lives.

To raise the funds he needed in order to return to America, Sokei-an worked in a factory for eight months. Then, in 1928, he returned to New York City, determining to be the first Zen Master to “bury his bones in America” and thus “mark this land with the seal of the Buddha’s teaching.” He supported himself by doing art restoration while he tried to determine how best to go about promoting the Dharma. He tried, like Christian evangelicals, going door to door offering to tell people about Buddhism, but that proved unsuccessful. He gave public talks in Central Park and at a bookstore on East Twelfth Street which specialized in Asian studies.

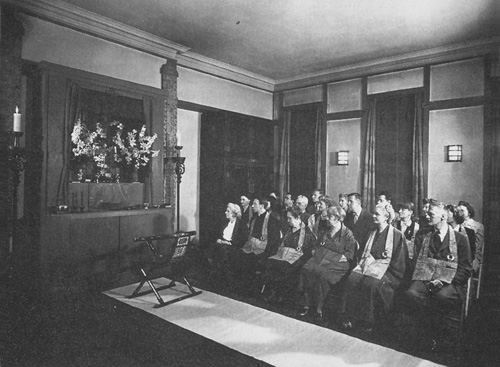

His first students were a group of eight Japanese businessmen who, in spite of the rupture between Sokei-an and Sokatsu, were successful in petitioning Ryomokyokai headquarters in Japan to authorize a branch in New York. They were incorporated in 1931 as the Buddhist Society of New York. Sokei-an tried, for a while, to teach his students to sit in full or half lotus posture and encouraged them to practice sitting that way at home. Even the students of Asian heritage, however, found the posture challenging so, instead, they used chairs during meditation sessions.

The focus of his teaching was the one-on-one sanzen interview – he called the sanzen room a “battlefield” – but he also gave powerful talks which could be witty and sharp. It was his physical presence, however, which most inspired his students.

One of these, Mary Farkas, described the format of the meetings of the Buddhist Society in an article published by the First Zen Institute of America in 1966. The gatherings took place in Sokei-an’s apartment where there was a small altar bearing only a stone. Sessions began with a short period of meditation. Farkas suggested it was Sokei-an’s silence which drew the participants into the meditation. “It was as if, by creating a vacuum, he drew all into the One after him.” Students working on koans were then called into sanzen in an adjacent room. During sanzen there were “no psychological or philosophical discussions, no worldly advice or explanations, just the business of Zen. When I was in recent years asked if we were given ‘instruction’ in Zen my considered answer had to be ‘no.’ To those of us who received Sokei-an’s teaching, the word ‘instruction’ must be a misnomer, for his way of transmitting the Dharma was on a completely different level, to which the word ‘instruction’ could only clarify the state of ignorance of the questioner. If I were to say he ‘demonstrated’ SILENCE, even that would be true but would give no indication of how he ‘got it across’ or awakened it, or transmitted it.”

Following sanzen, Sokei-an returned to the main room and took his seat behind a small desk on which he kept notes on the texts he was translating. He would read a passage from one of these then give an extemporaneous talk. He believed it was necessary to ensure that there were adequate Buddhist texts available for those who were serious about their pursuit of Zen, so he began an extensive translation project which included rendering the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch into English. He also translated The Record of Rinzai.

The group grew slowly but steadily. After seven years, there were thirty members. Sokei-an was not in a hurry. He reminded his students that it had taken hundreds of years for Zen to become established in China and Japan. What was required, he told them, was patience and perseverance. He told them of a monk he had once seen at a temple in Japan preaching to the rocks in the garden because there was no one there to hear him. Years later, when he chanced to pass the temple again, he found the same monk now preaching to a crowd of more than two hundred people. “I brought Buddhism to America. It has no value here now, but America will slowly realize its value and say that Buddhism gives us something that we can certainly use as a base or a foundation for our mind. This effort is like holding a lotus to a rock and hoping it will take root.”

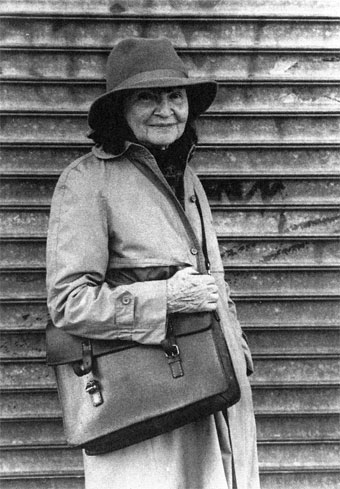

In 1938, the Buddhist Society acquired an unlikely wealthy sponsor, Ruth Fuller Everett, the wife of a prominent Chicago attorney, Edward Warren Everett. Their daughter, Eleanor, was married to Alan Watts. Ruth had only been eighteen years old when she married Everett, who was twenty years older. The marriage was not a happy one, and, in self-defense, Ruth developed a forceful personality in order to resist her husband’s tendencies to bully her. Once she gained the self-confidence to stand up to him, Everett resigned himself to allowing her to pursue her own interests.

In 1923, Ruth took her five-year-old daughter to a retreat at a country club outside New York City operated by Pierre Bernard, who called himself “Oom the Magnificent” and purported to be a master of yoga and a spiritual guide. Although Bernard was a fraud and a conman, the time Ruth spent with him fostered a genuine interest in Eastern Philosophy. When she returned to Chicago, she took up an academic study of Asian philosophy and languages at the University of Chicago.

In the 30s, she and Eleanor traveled to Japan where she introduced herself to D. T. Suzuki. He gave her some preliminary instruction in Zen but advised her that if she were serious she would need to practice with an accredited Zen master. He introduced her to Nanshinken Roshi, who, at first, was reluctant to accept her as a student. He had no other female students, and he doubted that pampered Westerners would been able to sit properly on cushions. Ruth persisted in seeking admission to the zendo, and finally Nanshinken arranged for a plush armchair which he installed in his house, telling her she could use it for meditation; however, only cushions were permitted in the zendo itself. Ruth learned to sit cross-legged and in a short time was practicing with the men in the zendo. Nanshinken came to admire her perseverance and eventually introduced her to koan meditation.

In 1938, Warren Everett was confined to a nursing home with arteriosclerosis, and Ruth moved to New York. She took an apartment in the city and arranged for her recently married daughter and son-in-law to occupy the one next to it. Learning there was an authorized Zen teacher in the city, she sought him out. She was not a passive student.

When Ruth met him, Sokei-an’s students were still meditating in chairs. From her own experience in Japan, she knew that westerners were capable of adopting formal meditation postures, and she took on the responsibility of teaching them how to sit on cushions. Soon she was tightening up other aspects of the Buddhist Society program.

Everett died in 1940, leaving Ruth more time to spend with Sokei-an. Part of their time together was work; Ruth remained a committed scholar as well as a dedicated Zen practitioner and, with Sokei-an’s help, she had undertaken to do an English translation of the eighth century Chinese Sutra of Perfect Awakening. But part of their time together was, to her daughter and son-in-law’s surprise, courtship.

In November 1941, just a few weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Ruth arranged for the Buddhist Society to move into more spacious quarters on East 65th Street. With the outbreak of war, the institute drew the suspicion of government officials. Suited FBI agents kept watch over who came and went. That July, Sokei-an—like Nyogen Senzaki—was arrested as an “enemy alien.”

He was sent to an internment camp in Maryland. The camp commander turned out to be a decent man who had some sympathy for those in his charge; Sokei-an took up his old calling and carved the commander a staff in the shape of a dragon. Conditions in the camp, however, were harsh, and Sokei-an was not in good health. He lost so much weight in the camp that he was able to tighten his belt four notches.

Ruth used her social connections to intervene on his behalf and was successful in arranging for his release in August 1943. The following year, they were married, in part to provide him some protection from still suspicious authorities.

After his release, Sokei-an told the members of the Buddhist Society that it was probably still too early for Zen to take root in America. The lotus still needed to be held to the rock a while longer. “I love this country,” he is reported to have said. “I shall die here, clearing up debris to sow seed. It is not the time for Zen yet, but I am the first of the Zen school to come to New York and bring the teaching. I will not see the end.”

His health didn’t recover, and he recognized that he did not have long to live. He assured others that he was prepared. “I have always taken Nature’s orders; I will do so now.” He tasked Ruth with the responsibility of ensuring that a formally trained Rinzai teacher be found to work with the Buddhist Society after his death. He also encouraged her to return to Japan to complete her own training.

He died on May 17, 1945, after less than half a year of marriage.

After his death, the Buddhist Society was renamed the First Zen Institute of America and committed itself to preserving Sokei-an’s teachings.

As Sokei-an had hoped, Ruth returned to Japan to continue her training. She approached Zuigan Goto, who had been a member of the group that had taken part in the feckless California farming venture with Sokatsu. Goto was teaching at Daitokuji, where Ruth was accepted as a lay student and given a small house within the temple grounds, separate from the monks who were all male and Japanese.

Sokei-an had also asked her to identify a qualified teacher to carry on his work in America, and, in 1955, after six years at Daitokuji, Ruth returned to New York with Isshu Miura.

In New York, Miura gave a series of talks on koans with Ruth acting as translator. These became the basis of a book they co-authored entitled The Zen Koan: Its History and Use in Rinzai Zen.

In 1957, Ruth returned to Daitokuji, where Goto allowed her to add a small zendo to the side of her house. This was the first zendo in Japan specifically intended to receive Western students. The following year, she became both the first woman and the first Westerner to be ordained in the Daitokuji temple system.

After Ruth’s return to Japan, Miura stayed with the First Zen Institute for a while, but he was not comfortable with the predominantly female board of directors. In 1963, he resigned his position, although he stayed in New York and maintained a small number of private students with whom he worked until his death sixteen years later.

One of the features distinguishing North American Zen from its Asian antecedents is the active participation of women in the sangha. Ruth Fuller Sasaki was the first of these, but she was not an easy person to work with. She was strong-willed, confident of her own opinions, and often inflexible. When she informed Zuigan Goto that she intended to add a dormitory to her small zendo, he told her he would rather she did not. She ignored his request and went ahead with the construction. In Japanese culture, it was unheard of for a student to disregard a teacher in this manner. It caused a rift between the two, and Goto disavowed her as one of his disciples.

Ruth gathered together a group of scholars in Kyoto to continue Sokei-an’s work of making Chinese and Japanese texts available in English. Several of these – including Philip Yampolsky and Burton Watson – later would become significant figures in the academic world. Working for Ruth provided these young men with an unparalleled access to rare documents, but they often felt that the specific tasks she assigned them were tedious and of questionable value. She was also quick to get rid of people with whom she disagreed or of whom, for whatever reason, she became suspicious.

Simple projects could balloon out of control under her direction. She began annotating the slim Zen Koan published with Miura, eventually adding over 150 pages of footnotes – in a smaller typeface – in addition to bibliographies, maps, genealogical charts and a “Zen Phrase Anthology.” By the time it was re-released as Zen Dust, shortly after Ruth’s death in 1967, it had swollen to a 574 page tome.

To the end, she remained a formidable personality, and often a generous one. Through her efforts, and those of the First Zen Institute, several Americans – including Walter Nowick and Gary Snyder – were able to travel to Japan in order to study Zen. In her way, she made as significant a contribution to the process of bringing Zen to North America as had her husband.

The Third Step East: 57-71; 9, 10-11, 73, 89, 100, 111, 127, 187, 188

The Story of Zen: 234-40, 251, 266, 280, 298, 424

One thought on “Sokei-an and Ruth Fuller Sasaki”