Open Mind Zen, Melbourne, Florida –

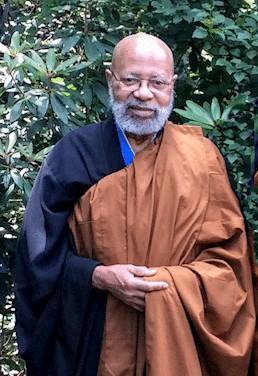

There are more than a dozen teachers identified on the Open Mind International website. Fusho Al Rapaport is the founder and director of the general organization and remains a teacher at the Melbourne, Florida, zendo although he tells me he no longer works much with beginners. His students are often people who have had years of prior Dharma experience. “A lot of the people who come to me are people who have studied in other traditions and in some cases gotten Dharma transmission from them but just feel they’re not entirely clear about what Zen, their life – whatever – is about, and so they want to clarify that.”

“So what is Zen about?” I ask. “What does it do for people?”

“What does it do for people? Generalizing is really tough. Sometimes people ask me, ‘What has it done for you?’ But since I’ve been doing it most of my life, it’s hard for me to know what it would be like for me without it. But I think – at least the way we work with it in our organization – that it’s basically a way of getting in touch with what’s really going on in one’s mind, in life, in relationships, and getting rooted in what’s real rather than what the mind is creating. And that’s a lifelong process; I don’t think it ever ends. As Dogen said, it’s practice/enlightenment. Meaning that it’s rolling along, and we’re practicing being awake and practicing awakening, and awakening is practicing us. So the awakening is resident in the practice; it’s not separate from it.”

When I ask how he first encountered Zen, he tells me that he first taught himself to meditate by following the instructions in a book he’d got from the Los Altos branch of the Long Beach Public Library when he was 17 years old. “There were things going on it my life that I couldn’t deal with psychologically. It was 1970, and, in the climate that I grew up in, it wasn’t like there was assistance if you were having psychological issues. It just wasn’t a thing. So I was in the library and checked out some books on yoga, and there was instruction in some of those books on meditation.”

“What was the psychological difficulty?”

“Originally? Falling in love for the first time.” We both laugh. “It was a woman. A woman who was beyond my ability to handle emotionally at the time for a number of reasons. And it started a kind of a cascade within me, a kind of an emotional cascade I wasn’t equipped fully, at the time, to deal with psychologically. And the meditation really helped me work with what I was feeling. Probably also helped me by-pass some emotional content,” he adds, smiling. “But it did help. I started doing yoga regularly and meditating from the books. I didn’t have a teacher. I don’t think there was a yoga teacher in all of Long Beach at the time. If there was, I didn’t know of them. So other than the books, I didn’t have any other resources. And I gradually I began connecting with people who were into alternative things like that, but I didn’t meet my first Zen teacher until 1975.”

One of Fusho’s friends at the time was Steve Young – later Shinzen Young – who would also become a meditation teacher. “He was a Buddhist monk, and we became friends before I met my first Zen teacher. He had studied in Japan and was living at a Center in LA called the International Buddhist Meditation Center which was pretty close to the Zen Center of LA. And he was the one who introduced me to Kozan Kimura who was my first teacher.”

I am not familiar with Kimura.

“Well, that’s because he was only in the US about a year. I didn’t meet him until about halfway through his trip. He was Japanese, didn’t speak English. He did travel with a woman who was a translator slash girlfriend I believe. I was living in Colorado for a while and while I was back in LA visiting family, I called Shinzen up, and we met for lunch. He said, ‘I’m studying with this Zen teacher.’ He was also translating for Joshu Sasaki Roshi at that time ’cause he’s fluent in Japanese and several other Asian languages. So I met a number of Zen teachers in LA about that time, but Kozan Kimura was the first one, and I had an immediate connection with him. It’s like the minute I met him, I knew he was my teacher. I’d never had that feeling before at all. And I’d been looking I think, even though I didn’t realize I was looking.

“Once I realized he was my teacher and that I wanted to study with him, I went back to Colorado, got rid of all my stuff there and came back to Southern California. But I didn’t have a car at first, so I had to take buses from where my mom’s house was in LA, and then walk in south-central LA – which was a pretty dangerous place at that time – to get to this little house he had in South Central LA.”

“I’m wondering why you did this.”

“Why I was meditating?”

“Well, maybe why did you think you needed a teacher so badly that you were willing to brave the streets of south-central LA to work with one?”

“As I said, I didn’t realize I was looking for a teacher before that. It’s kind of like if you’ve ever fallen in love at first sight? I just realized intuitively that he was my teacher. We could say that it was karma, that we had past karma. That’s possible. Who knows? That’s certainly a possibility. I don’t opine on those ideas much because I can’t prove them one way or the other, but it’s how it felt. When I met him, I felt like I knew him and that I needed to study with him.”

During the next six months, Fusho spent as much time as could with Kimura, but eventually the teacher returned to Japan. “So I essentially started looking at different communities in LA, and since my friend Shinzen was translating for Sasaki Roshi, I spent a fair amount of time listening to Sasaki Roshi’s Sunday talks. I did a retreat with him at Mount Baldy Zen Center, but due to something that happened during the retreat, I decided not to stay with that organization. Then I ended up at the LA Zen Center.”

“Are you willing to tell me what happened at Mount Baldy?”

“Well, Sasaki basically – as he was known to do – accosted my girlfriend in the interview room during the first interview. That was the kind of stuff that guy did. And I just couldn’t get over that he’d done that in the interview room so I started looking around more.”

The Zen Center of Los Angels, he tells me, “Had a huge residential community. And that really appealed to me. I did a retreat there in ’77, and I think I moved there in the winter of ’78. So a little over ten years after they started. I was in the training program for three months, then I ran out of money, and they put me on staff. And I was on staff there for about a year or two. And I decided not to stay on staff, but I lived on the same block. I had a job outside of the Zen Center and rented an apartment.”

But there were problems at ZCLA as well. Among other things, the Roshi, Taizan Maezumi, was an alcoholic.

“Towards the end of my residence in LA there, the community had reached the size that the zendo was nowhere near large enough for everyone to sit in. I think we could sit maybe sixty or so in the big zendo, and then we had a smaller one which fit maybe twenty-five or thirty in. And during retreats there were sometimes more than that sitting, so they were trying to raise money. They did this big fund-raiser to try and raise money for this building, a Japanese-style zendo that they were going to build. They had a well-known LA architect who had come up with architectural renderings of what it would look like. And they did this fund-raising dinner which was supposed to court donors in the LA area, a lot of whom were members of the center. There were a lot of members who had money. Certainly those of us practicing there didn’t, but people who didn’t live there, some of them were professionals in the entertainment industry and other businesses. So the big highlight of the night was supposed to be Maezumi Roshi giving this talk at this dinner. And he walked up to the mike when it was his turn to speak – and we were all drinking a lot, don’t get me wrong; it was kind of a party scene at that point – and he was laughing, and, if I remember correctly, he said something like, ‘I wonder why you’re all here tonight?’ Something like that. And he just laughed and turned around and left the lectern. There was this murmur that went out in the crowd, and then somebody else came up and jumped in ’cause it was obvious that that was all that he was going to say. He wasn’t going to give this big inspiring speech about how we needed to raise money for the zendo. So you could say either that he was being an enigmatic Zen master or he was so drunk he didn’t feel he could speak, or both, and I don’t know which is true. But the effect of it was that some of the donors were really pissed off afterwards, including the architect who had been donating his time. And the whole thing fell apart. I never heard about that project much again. Which is sad. It would have been a really amazing thing if they’d been able to pull it off.”

Fusho didn’t work with Maezumi directly.

“When I first arrived at Zen Center of LA, both Maezumi and Bernie Glassman were in Japan. Bernie was Maezumi’s first successor, and at that time he was taking successors to Eihei-ji in Japan to do this really traditional week-long thing at Eihei-ji. So they were gone for a few months, and during that time Maezumi had left Genpo in charge, Genpo Sensei at the time. So my first introduction, I walked into the interview room in the retreat I did in ’77, bowed and looked up. I expected to see a Japanese man sitting there but instead it was Genpo.”

Genpo is Genpo Dennis Merzel a Maezumi heir who would later be censured for his sexual affairs.

“And we started talking. Turned out we went to the same high school, grew up in the same town, knew some of the same people, used to go to some of the same beaches. He’d been a lifeguard back then. So, I ended up feeling a connection with him. As you can tell from the way I described meeting my first teacher, my connection with teachers has always been a highly intuitive process where when I met someone who was my teacher, I just immediately knew it. So when people say, ‘I don’t know how to find a teacher,’ I don’t know what to tell them.”

When Genpo left Los Angeles to establish the Kanzeon Zen Center in Salt Lake City, Fusho moved there for a time to continue studying with him. I ask how he supported himself through all of this, and he explains that he organized conferences.

“Originally they were holistic health conferences, then I moved into yoga conferences. I was working with Yoga Journal for a few years. And then I started doing Buddhism conferences. They were called ‘Buddhism in America.’ I did one in ’96 in Boston; I did one in San Diego; I did one in Estes Park with the Naropa Institute, and then I did one in New York with Tricycle magazine a few months before 9/11, right down there where it happened, the World Trade Center’s Marriott. So I produced conferences, and that gave me the money and the freedom to do the kind of meditation practice and retreats that I wanted to do. My guess is I’ve done a lot more retreat time than most lay people because I had a schedule that allowed for long retreats.”

“What drove you to keep it up?”

“It felt like I was going into something more deeply all the time. Reality or whatever you want to call it. Buddha Mind. I was also practicing koans. I think that I had a desire early on to be a teacher. Not everyone does. But I was working through the White Plum koan system, so I worked with Genpo.”

“When you say you thought you’d like to be a teacher, what did you think that meant?”

“Well, at the time I had no idea of what it would amount to,” he says, laughing. “That’s been an on-going discovery over the years that I have been officially – and before that, unofficially – teaching. Just that I felt I was in contact with something that I could share, that I could somehow make a contribution to helping people free themselves from suffering or whatever, which I felt I had done to a large degree. I think that because I started so early, that Buddha Mind was something I really connected with from virtually the first time I meditated when I was 17. So that’s what I felt I was able to communicate to people. It felt like the right thing to do, and I did it. When I moved to Western Massachusetts in 1983, there was no Zen group in the town I was living in, so I set one up.”

“And how did you get to Massachusetts?”

“Well, I met woman in LA at a conference who I ended up getting involved with. And for a few months we were doing a back and forth. She lived in Boston, and I lived in LA. So around ’82 I decided to move to the Boston area to be with her, and then about a year later we moved to Western Massachusetts because we wanted to get out of the city. And there wasn’t a group there, so I knew Daido Loori had his group in New York – it was only about a three-hour drive from where I was living – and I called him up, and I said, ‘Would you be willing to come out and do a talk? ’Cause I’d like to start a sitting group.’ And he said, ‘Sure.’ So he came out and gave a talk. I think about twenty-five people showed up most of whom I didn’t know; one or two I did. And at the end I said, ‘Does anyone want to continue as a sitting group?’ And about twelve or thirteen people said yes, so we started a sitting group.”

Meanwhile, he continued his own training first with Maureen Stuart – also known as Ma Roshi, who had been authorized to teach Zen by the Japanese teacher, Soen Nakagawa – and later with the late Jules Shuzen Harris, an heir of Enkyo O’Hara.

“I got Dharma transmission in 2008 from Shuzen Roshi. He had a center in Philadelphia and was a friend of mine from Kanzeon in Utah. We had both left Genpo at different times. I actually started teaching unofficially when I moved to Florida in 2001. I wasn’t certain at that time that I wanted to get Dharma transmission and go that route. I’d been authorized as an assistant teacher by Genpo before I left Utah, but I didn’t get full Dharma transmission until Shuzen.”

“Did it make any difference to the people you were working with whether you had full transmission or not? Did they care?”

“No. Basically they knew I knew what I was talking about at that point. So we’re talking around 2001, and I started Zen practice in ’75. I already had twenty-six years of Zen practice and thirty-plus years of meditation practice at that time. So, you know. I do believe the whole Dharma transmission thing is valuable – and I do it myself – but it doesn’t guarantee that anyone’s a good teacher. And these days there are a lot of people with Dharma transmission who don’t have a tremendous amount of experience in my opinion. Each teacher has different metrics about how they determine that. Actually going through the process of getting Dharma transmission alienated some people,” he says chuckling. “Because I think things were looser before. Once I had Dharma transmission, I tightened things up a bit.”

He called his Florida community Open Mind Zen. There are now affiliate groups in Indiana, California, Kentucky, and Germany. The focus of Fusho’s teaching is on koan work.

“Koan study is a unique form of spiritual practice unlike anything else that I know that exists in any other religion. At least in a formal way. There’s some of it in some religious practices, say in Sufism and few other places here and there, Tibetan Buddhism. But koans aid us in getting in contact with the non-logical, intuitive part of the self, which – I believe – Zen training is oriented in getting us in touch with. And it does so in a systematic way, approaching it from many different angles over years of practice. It helps us to drop self-consciousness because when working with koans you have to present things in a very unselfconscious manner. Dropping the sense that we ‘know.’ Because people who are highly intellectual don’t like not knowing what the answer to a koan is.” He smiles. “I know this because I had that experience when I was working with them. So there’s a lot of value to working with koans. Hearing the stories of ancient teachers and how they related to students and each other. Learning to drop self-consciousness, helping to get in touch with – again – Buddha Mind, True Nature, whatever you want to call it.”

We discuss some of the technicalities of koan practice, especially expectations around the first koan students are given. In many instances it is “Mu,” the classic story of Zhaozhou’s response to a monk who asked if a dog had Buddha Nature. In the tradition in which I trained, Mu was considered a breakthrough koan, one of a handful of koans to which the only acceptable response was some degree awakening.

Fusho nods his head. “Yeah, I understand that. I don’t treat it that way, and it’s a really involved discussion. I will say this about the initial breakthrough koan and that whole issue: First of all, when I did training at the Zen Center of LA, my teacher treated Mu as a breakthrough koan, and it took me about a year and a half to pass Mu. It was really an intense experience when I did. I went through the classic stages of it, getting into a state of Great Doubt and all that beforehand, being with me day and night, the hot iron ball that I couldn’t swallow, and all that. It all happened to me. So you have to understand that the position I have now is based on experiencing that. So I did a quote/unquote ‘traditional training,’ and to me tradition is just someone started something, a lot of other people started with the same thing, and then it becomes a tradition for a certain amount of time. But someone had to start the method. So over the years, having had numerous opening experiences, and now practicing meditation for over fifty years, I have come to the conclusion that when you build up in your mind that something’s a breakthrough koan, then that’s what it becomes. And the pressure – psychological and physical pressure – that is developed over working on a koan in that kind of environment works for some people, but it’s actually psychologically harmful for others. Especially anyone who comes from a trauma-based background. And so I approach koans in a very different way now where people do have to come to the correct answer but perhaps in a different way. And I break Mu up into a few different parts. And some people have a real breakthrough, and others just slide into it. And I think part of it is that I’m dealing with people who are coming to Zen with a much more mature perspective than I did when I started. I was quite a mess when I started Zen practice is probably the best way to put it. So I needed that psychological pressure at that time, but I don’t put that kind of pressure on people I work with. I do a process with new students called ‘Zen Dialogue.’ It’s a system of dialogue, and one of the things we do in that technique is we work with people in getting in touch in a direct conscious manner with Buddha Mind or whatever they call it in their particular way of viewing it. So I use different kinds of techniques to get people to see that, and sometimes it’s a big bang, but most of the time it’s not. And I find that if you don’t set up in your mind that there’s this big barrier that you have to break through, then guess what? It’s not a big barrier which you have to break through.”

As our conversation winds down, I return to something he had said earlier.

“You suggested that Sasaki didn’t live up to your concept of how a Zen Master should behave. You’ve actually encountered a number of authorized, often deeply respected, Zen teachers whose personal behaviour has been problematic. Sasaki, Maezumi, Genpo. So, people with teaching authorization and transmission can still have messy lives?”

“Oh, yeah. Absolutely. That’s one of the reasons why in our school I like to have people do other psychological work rather than just straight sitting practice and koan practice. Because you can sit for a long time and do koans for many, many years and still not work with psychological and trauma-based issues going on within you. There’s a number of ways to get at those other issues, but I think they have to be addressed. One of the things that’s happening in the Americanization of Zen, there’s a lot more women practicing. There’s probably an equal number of women and men teachers now. And there’s a lot of psychotherapists and social workers and people in counseling professions doing it. And so there’s been an element of that brought into Zen where these days if you try to away with the stuff that the teachers back in the day that I started out did, you couldn’t. You’d be excoriated immediately on the internet and called out for it. Whereas back then, people could do things, and it could be hidden quite easily for many years sometimes by other people that knew what was going on but then regarded these teachers as the ultimate guru-like authority. So I don’t think that exists much anymore. There’s an openness now – hopefully an openness – in Western Zen which has developed as a result of women being equal and also Western psychology being incorporated as an element.”

“Are you saying that the concept of a Zen teacher as an exalted figure with guru-like authority has diminished to some extent in North American Zen?”

“Definitely. Yeah, definitely. There’s a sense, I think, that the original teachers because there were very few of them and they were Asian and exotic, wore exotic clothing . . . This wasn’t just in Zen. This is something that occurred in all different disciplines that came over from Asia, the yoga tradition, other meditative traditions, the original teachers were like godlike almost – and in some cases they encouraged this – they were viewed as ultimate authorities who in many instances could essentially do anything they wanted, and people would accept it as stuff they needed to work on if they didn’t like it. That doesn’t exist much these days. Someone who’s abusive of women or whatever is not going to last two hours as a teacher. They’re just not. Whereas that could happen for decades previously.”

I mention someone who told had recently told me that her only meeting with Joshu Sasaki had taken place when he was over 100 years old, and he still tried to pull her to him.

“That just confirms what I said earlier. When someone has an addiction like that, you can sit for 100 years and not necessarily work on those kinds of issues. It wasn’t part of Asian teachers’ tradition to do psychological work. Although evidently Maezumi tried.”

“He went into therapy,” I point out. “He entered a rehab program.”

“True, but he still ended up dying essentially from drinking too much from what I understand. It takes work to get over that kind of addiction that I think many teachers wouldn’t do because there were enough people still treating them as gurus. And this reflection on the psychological underpinnings and the trauma-based underpinnings of peoples’ addictive behaviours didn’t exist in Asia, as far as I know. There’s a discussion that could be had about why things happened the way they did – and I have ideas based on my experience – but all I know is that it doesn’t work now.”