Kwan Um School of Zen –

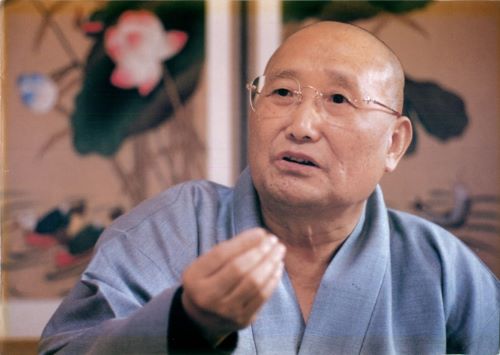

The Kwan Um School of Zen (or Seon in Korean) began in Providence Rhode Island in 1983 and is now a global phenomenon. Its founder was the Korean monk, Seung Sahn, originally a member of the Chogye Order in Korea. He came to the United States in the 1970s while in his mid-40s, arriving with only a smattering of English, and supporting himself by working as a handyman in a laundromat. His story is one of the most remarkable in the history of North American Zen.

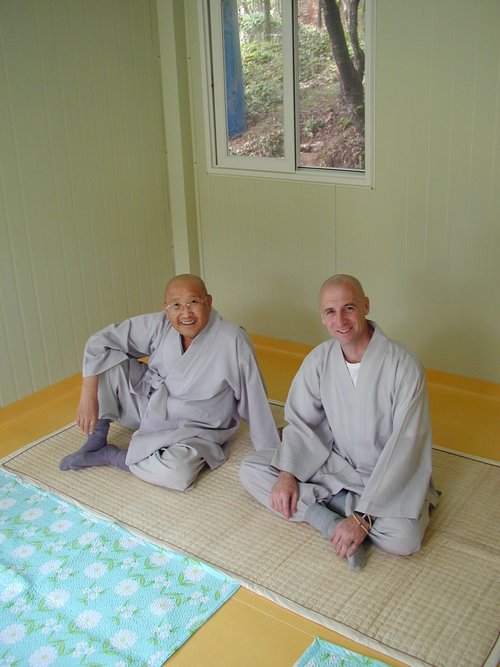

Dae Bong Sunim is one of Seung Sahn’s Dharma heirs and the Kwan Um Regional Zen Master for Asia, Africa, and Australia.

“Zen Master Seung Sahn was born in 1927,” he tells me, “outside the city of Pyongyang. At the time Korea wasn’t separated, but it’s in what is now North Korea. He grew up during the Japanese occupation, which was probably one of the most significant issues of his childhood. His family were Protestant Christians, although I don’t know how active he was.”

His birth name was Duk-In Lee, and, as a teenager during the Second World War, he and a group of friends made a radio with which they could listen to what Dae Bong supposes was “The Voice of America.”

“Of course, they were strongly opposed to the Japanese presence. He said that when he was young, he only felt one thing, ‘Free my country.’ Amazingly, perhaps his best friend in America was Maezumi Roshi who was Japanese. It was a great teaching to us to see their friendship given their countries’ history.”

Almost all of the people I spoke to about Seung Sahn imitate his accent when describing him. Dae Bong suggests it was because the accent was cute and charismatic. Judy Roitman, however, thinks “forceful” is a more appropriate term. “Soen Sa Nim’s English was never fluent, but it was direct and expressive, and the accent was part of it. His speech was more powerful than if he’d enunciated everything correctly. It felt as if his limited English forced him to go directly to the heart of things.”

“He was arrested because of the radio,” Dae Bong continues, “and then he was let out of jail when his high school teacher spoke up for him. Then he and his two friends stole some money from their parents and went up to Manchuria to join the Korean Free Army to fight for the liberation of Korea. There they met up with one of his friend’s older brothers who was in the KFA. They intended to join as well but were told, ‘Go back and finish high school.’ So he finished high school, and when the war ended – as you know – America and Russia supported the division of the country. Seung Sahn Sunim’s parents sent him and his younger sister to the south while they stayed in the north to take care of their parents. He and his sister never saw them again.”

Eventually he entered university where he studied Western philosophy.

“He really liked Socrates. He always talked about Socrates walking around Athens saying, ‘Know thyself! Know thyself!’ One of Socrates’ students said, ‘Teacher, do you know yourself?’ He said, ‘I don’t know, but I understand this “don’t know.”’ Soen Sa Nim really liked that.”

It takes a while for me to catch that sometimes people refer to Seung Shan as “Soen Sa Nim,” which sounds – to me at least – very similar, and I have trouble distinguishing when which is being used. “Soen Sa Nim,” Judy explains, is both a title and an expression of affection. “Soen Sa means Zen Master, and Nim is an honorific that has a tinge of ‘beloved,’ so it’s not just that you’re looking up to someone, but you’re looking up to someone with affection and love.”

Then during the General Strike of 1946, Seung Sahn observed rival factions in South Korea fighting in front of the rail station.

“This really hurt his mind,” Dae Bong says. “Growing up all he wanted was ‘my country be free’ and now that the Japanese were gone, the Korean people were fighting each other. He became disgusted with society and went into the mountains saying he wasn’t coming back until he understood the truth of human life.”

Judy tells me that he stayed in one of the small cabins attached to a Buddhist monastery, where he continued to read Western philosophy until one of the monks asked him why – as an Asian – he wasn’t reading Asian philosophy. The monk gave him a volume that included, among other things, the Diamond Sutra.

“One day,” Dae Bong explains, “he came to the line in the Diamond Sutra that says, ‘If you view all appearance as non-appearance, this view is your true nature.’ At that moment, his mind became clear. He realized the truth, but also realized that understanding it is not enough. It must become your lived experience. So he decided to become a monk. Soon after becoming a monk, he asked an older monk, ‘What is most difficult kind of practice?’ The older monk told him to do a 100-day retreat chanting the Great Dharani for 20 hours every day, get up for two hours in the middle of the night, pour cold water on yourself outside in the winter and then chant for two more hours. And only eat crushed pine needles. He asked the monk, ‘What is the result?’ The monk replied, ‘Three possibilities: get enlightenment, go crazy, or die.’ Soen Sa Nim thought, ‘Get enlightenment or die is okay, but going crazy not so good.’”

The story continues that Seung Sahn achieved enlightenment during this regimen, after which he went to see Zen Master Kobong who was considered the toughest master in Korea. “He showed Zen Master Kobong a moktak[1] and asked, ‘What is this?’” Dae Bong tells me. “Kobong Sunim hit the moktak with a stick. Seon Sa Nim thought, ‘Ah my mind is the same as his,’ and turned to leave. Then Kobong Sunim said, ‘What did you see? A bird, a building, an airplane?’ Seon Sa Nim turned around and asked Kobong, ‘How can I practice Zen?’ Kobong Sunim asked him a traditional kong-an[2] which he didn’t know how to answer, and he said, ‘Don’t know.’ Then Kobong Sunim told him, ‘Only go straight “don’t know.”’”

After sitting the traditional three-month retreat the following winter, Seung Sahn visited Zen Master Kobong again. After Kobong tested his comprehension of several koans, he acknowledged the younger man’s enlightenment. Seung Sahn received transmission from him in January 1949. He was 22 years old.

The following year, the Korean War broke out, and Seung Sahn was drafted into the Korean army. “He told us that while he was in the army, he experienced something which touched deeply him. He was in an area where some American troops were having a meeting. They had chairs set out and a raised platform. There was a big map, and a lieutenant on the platform. There was going to a be a briefing about the day or plans for the next days. Even though he didn’t know the language, Seung Sahn could tell that the enlisted men sitting in the chairs and the officer were joking back and forth. He said you never would see this in the Korean army. In the Korean army due to Confucian sensibilities officers and enlisted men were very separated in terms of their behavior with one another. But the American soldiers were joking back and forth with the officer like equals, and it wasn’t a problem. Then a colonel came in. The lieutenant said, ‘Ten-hut!’ and everyone stood up and saluted. Then everyone smoothly separated into their jobs, no longer ‘equal’. That really touched him, that insight: when it’s not job time, everybody’s equal. When it’s time to do our job, you separate because of your job. In the Korean Confucian approach that had developed for centuries, people were strictly separated by social positions or jobs. This moment of equality between the soldiers and the officers affected Soen Sa Nim very much, and he developed an interest in the United States.”

Conditions in the Chogye Order were messy in the 1950s, and Seung Sahn felt that if the order didn’t modernize its approach, particularly its attitude to lay people, it wouldn’t – as Dae Bong put it – “be able to connect with modern Korean society in the future. So he got the idea of going to teach in America. In 1966 he was invited to Japan by the Japanese government to help the Koreans living in Japan. And then in 1972, he flew to America.”

America was a common destination for Zen teachers at the time. Taizan Maezumi went to Los Angeles in 1956; Shunryu Suzuki came to San Francisco three years later; Joshu Sasaki arrived in 1962. The question is why Seung Sahn chose to set up shop in Providence, Rhode Island.

“That’s a good question,” Dae Bong admits. “He landed in LA, and soon Korean Buddhists knew a Korean Zen Master was in town. They gathered around him and asked him to make a Buddhist Temple. He did. But after a few months, he realized, ‘If I stay in LA or go to Chicago or New York I will be surrounded by Koreans and not be able to meet westerners.’ So he told the Koreans in LA, ‘I’m going to the East Coast; I’ll be back in a few months.’ On the plane he met a Korean man who had been living in America a long time, and Soen Sa Nim told him, ‘I want to meet American people.’ This man told him that on the East Coast there is a small town, Providence, probably about 200,000 at that time. It has a very good university, so you can meet young American people there. And there’s almost no Koreans there. He went there and got a job taking care of a laundromat and rented a small apartment. That’s how he ended up in Providence.”

“Then what?” I ask. “Put up on posters on phone poles saying ‘Zen meditation this way’?”

“Almost. The Korean word is ‘Seon’ and the Japanese word ‘Zen.’ He knew Americans knew the word ‘Zen’ so he went around the town, probably to the university, and put up signs that said ‘Zen’ and gave his apartment’s address. And students started to show up. In 1972, many young people were interested in Zen. Zen Master Seung Sahn has a great face and bearing. When people met him, they became interested immediately. He said he made noodles or soup for anyone who came ‘because students are always hungry.’ Then he’d take them into the other room and point at sitting cushions he had; he’d sit down himself in meditation position. People would look at him, and they’d just copy it. He couldn’t talk to anyone because he knew almost no English. Then one of the students realized that Soen Sa Nim spoke Japanese because he grew up during the occupation of Korea and had to speak Japanese in school and outside the home. One of the professors at the university spoke Japanese. The student introduced the two of them. Then the professor – Leo Pruden – would come over to the Zen Center on certain days and translate Soen Sa Nim’s Dharma talks from Japanese to English. At some point about eight young people had moved in with him. It was just a little house; the students shared a bedroom. Soen Sa Nim had a bedroom, and the living room was the meditation room. They got up early every day, did 108 bows, chanting, and sitting. After breakfast the students would go to school and one of the students – Bobby Rhodes – she would go to work. She was a nurse. Soen Sa Nim would go to work in the laundromat.”

Bobby Rhodes – Zen Master Soeng Hyang – is the current Kwan Um School Zen Master. She was also the first member of the Kwan Um School I interviewed back in 2013. When I asked her how she had first found out about Master Seung Sahn, she told me, “I didn’t find out about him, ’cause nobody knew him. But I was looking for an apartment, and the apartment that I looked at was above his temple. I didn’t take the apartment, but I came back a couple of weeks later and knocked on the door and met him.”

“What was that meeting like?

“I had been scared to go back, because I’d read all these Japanese books about getting hit. So I was afraid he’d be too severe. But it was great. He was down on the floor doing calligraphy, and he was very sweet and friendly. And there was an American Brown University student there who walked me around the apartment, showed me things, and introduced me to Master Seung Shan. And then, when I was leaving, he spoke hardly any English, but he said, ‘Come back! Come back! We have a Dharma talk on Sunday.’”

Bobby did come back the following Sunday, and, shortly after, she moved into the “temple.” “It was just an apartment,” she explains. “There were three of us. We had a big living room that we turned into a zendo and put up an altar, and it had a kitchen and two bedrooms. So I just slept out in the Dharma room. I was a hippie. So I was fine. I was used to sleeping on the floor. We were young. Very young. I was twenty-four. I could sleep on a dime. It was simple.”

When Dae Bong first came to the temple, Seung Sahn’s status had changed. “By the time I appeared, there were six Zen centers under his direction. Four on the east coast; two on the west coast, and groups in Toronto, Chicago, Kansas, and – I think – Colorado. What attracted me? First, it was Zen Buddhism. Second, I liked the chanting, chanting the Heart Sutra. The people were quite natural. Bobby gave a talk, and it was basically about how at work that day, she was going to open up a banana for one of the older patients she took care of, and the guy said, ‘No! You open it from the other end.’ She said, ‘No. We always open it from this end.’ And he said, ‘No, I saw some chimpanzees on TV, and they open it from the other end,’ and he opened it from the other end, and it worked quite well. I thought, ‘Well, that’s a stupid talk but simple and clear. There’s not only one way to do things.’”

Seung Sahn had not been at the first gathering Dae Bong attended. They didn’t meet until Dae Bong signed up to attend a three-day retreat.

“The first night when I went down there, as soon as I saw Soen Sa Nim, I had a very a comfortable feeling. What really struck me though was when during the Dharma talk and Q&A someone asked him, ‘What is sanity? What is insanity?’ He didn’t understand those two words and turned to his student and said, ‘This man. What say?’ The student understood Soen Sa Nim’s English and said, ‘This man asked, “What is crazy; what is not crazy”’ I was curious right away because I had studied psychology in university and worked in a mental hospital and on the psychiatric ward of a prison. Zen Master Seung Sahn said, ‘If you are very attached to something, you are very crazy. If you are a little attached to something, you are a little crazy. If you are not attached to anything, that’s not crazy.’ I thought, ‘That’s better than the eight years that I studied and worked in psychology.’ Because it covers everything: religious people, successful people. Everyone. And he kept talking. ‘So, in this world everybody’s crazy because everybody’s attached to “I.” But this “I” is only made by our thinking. Originally it doesn’t exist. If you don’t want to attach to your thinking “I,” and realize your true “I,” you must practice Zen.’

“We started the retreat next morning; a lot of people were there only for the talk. Zen Master Seung Sahn gave private interviews to each student every day. At my first interview, he asked me if I had any questions, and I said, ‘No.’ Then he gave me his basic Zen teaching ending with: ‘your before-thinking substance, my before-thinking substance, this stick’s substance, the substance of the sun, moon and stars, all universal substance is the same substance.’ At that moment I thought, ‘I’ve been waiting my whole life to hear that.’”

By the mid-80s, Seung Sahn had a well-established network of centers and was generally admired by Zen practitioners in other traditions as well. But the 80’s was a stressful time within North American Zen. In 1982, a number of Eido Shimano’s students left his sangha because of his sexual misconduct. In 1983, Richard Baker was pressured into resigning as abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center in part because it was known he engaged in affairs with students and with the wife of a major financial donor. In 1984, Taizan Maezumi in Los Angeles – who also admitted to having affairs – entered a rehabilitation clinic for alcoholism. 1988, one of Joshu Sasaki’s students published a poem in which she accused her teacher of sexual abuse. And that same year, Seung Sahn also acknowledged that he had been engaged in relationships with students.

Judy Roitman insists, however, that Seung Sahn’s situation was different from those other teachers. “He was not a predator. So in Korean culture there is this kind of accepted — not considered a good thing, but tolerated — situation of a student, who is female, having a sexual relationship with a monk. It’s tolerated but it stays in the shadows. And so Zen Master Seung Sahn had relationships. But they were relationships. He was not a predator. I know people he had relationships with. And if you talk to them about it – which I have – they will tell you that this was not a damaging relationship. It was not something that was destructive. They just had this monk boyfriend who was also their teacher, which is breaking all kinds of bounds, but this was back when people didn’t understand things like that. I have been with predators. These were people who destroyed peoples’ psyches. These were people who were like crocodiles waiting on the bank waiting for a nice young hippo to go into the water and slithering to attack them. Master Seung Sahn was not like that.”

I ask if the revelations of those relationships had the same impact on the Kwan Um community that it had in other communities.

“The revelation did have a very strong impact. There were people who left. However, he did something those other guys didn’t. He apologized.”

Judy also points out that the Kwan Um school was “one of the first Buddhist organization in America to come out with an ethics policy. I still think it puts too much emphasis on sex because I see sex generally as a symptom rather than the disease. The underlying disease tends to be issues of arrogance, pride, and feelings of being special: ‘I can do anything I want.’ But we’re very clear about the process of a teacher and a student wanting to have a relationship, what this means and how they can go about it in an ethical way. Basically they have to be open about it, and they can’t have a teacher-student relationship if they’re going to have an intimate relationship.”

Towards the end of his life, Seung Sahn’s health deteriorated. He had a pacemaker inserted in 2000 and died four years later. The Chogye order honored him with the title “Dae Jong Sa” – Great Lineage Master – but the Kwan Um School continues to retain its independence.

I ask Dae Bong if the words “Kwan Um” mean anything, if they can be translated into English.

“Kwan means ‘perceived,’ and um means ‘sound,’ and it’s the name of the Bodhisattva of Compassion . . .”

“Oh, shoot,” I say interrupting him. “Kannon.”

“Yes, it means ‘perceive the suffering of the world and help. Be a Bodhisattva.’”

“I should have figured that out on my own.”

“Well, that was Soen Sa Nim’s teaching. Zen doesn’t always have compassion at its core. It has compassion but not always at the core. But that was the core for Soen Sa Nim, ‘Realize your true nature and help others. Your compassion will naturally come out.’ That is the Kwan Um School of Zen.”

[1] A wooden instrument that is hit during chanting to regulate speed

[2] The Korean term for koan.

7 thoughts on “Seung Sahn”