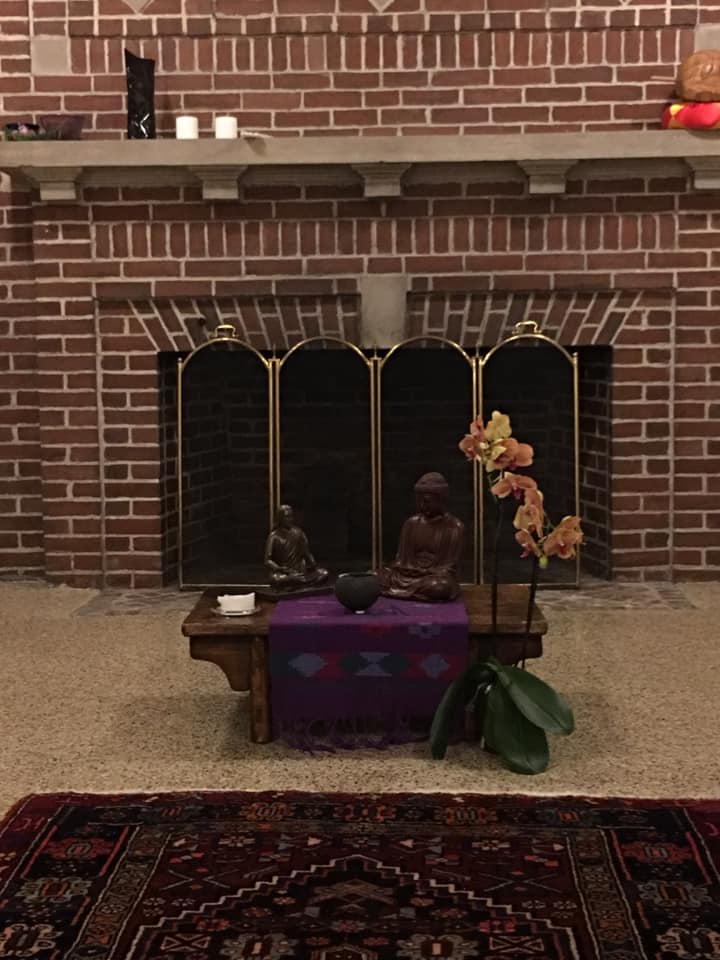

Day Star Zendo – Wrentham, Massachusetts –

I met Sister Madeleine Tacy in 2016 when I visited the Day Star Zendo in Wrentham, Massachusetts. That visit is described in the final chapter of my book, Catholicism and Zen. Seven years later, she is now the guiding teacher of Day Star. The group had been started by Father Kevin Hunt, a Trappist monk as well as a transmitted Zen Master, now retired. He was succeeded by Cindy Taberner who withdrew from teaching for health reasons.

“I know this is still new for you,” I say, “but what do you think the community is looking for from you?”

She considers the question a moment.

“Well, I think they want things to continue. And nobody seemed to say they were leaving because, ‘I don’t want her as teacher.’ Some of them I’ve only met on Zoom, to be honest. The pandemic did that. And there’s a group that have known each other for longer than I’ve been around. Which is fine. So I think it’s a responsibility to carry on what was started with the group. And do the best I can do; that’s all I can do.”

“That doesn’t really tell me what they’re expecting from you. What is it they look for from a teacher?”

“Well, I hope it’s not the answers, because they have the answers. I don’t. I think maybe it’s somebody that’s going to point the way, but they have to find out for themselves. You know the old koan about don’t confuse the moon with the finger that points at it. I think the people that are there are serious about their practice. Maybe they’re looking for encouragement. Maybe also a little prodding to go beyond. Whatever that means.”

Madeleine is a sister in the Dominican order, and she tells me she entered the convent after high school. Her mother was supportive from the start, but her father was less so. “He tried to bribe me. If I didn’t go, he would buy me a car. And at that time – that was ’57 – so that would have been a real status symbol, but – no – I went.”

1957 was still well before Vatican II, and the Catholic church was very traditional, especially in rural areas like the one where Madeleine grew up. She remembers her father, for example, kneeling by his bed at night with his prayer book before turning in. After the council, she became curious about other forms of spirituality and did a master’s degree in history “on the historical development of the hesychast tradition and Chan Buddhism in China which happened – time wise – about the same era.”

Hesychasm was a form of monastic life in the Orthodox Church which sought divine quietness (“hesychia” in Greek) through which one can attain experiential – as opposed to theoretical – knowledge of God. The hesychast “Jesus prayer” – in which the phrase “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me” is repeated silently in sync with one’s breath – became popular in the early 1960s in part because of a 19th century volume called The Way of the Pilgrim which was described in a couple of New Yorker stories by J. D. Salinger and later brought together in a book entitled Franny and Zooey.

“How did you become interested in hesychasm?” I ask.

It began, she admits, through reading, although I suspect it wasn’t reading Salinger. And then there was the impact of the Second Vatican Council.

The council was convened in 1962 by Pope John XXIII, who declared that it should “Throw open the windows of the church and let the fresh air of the spirit blow through.” It was a broad renewal of every aspect of church life. John died before the council was completed, and his successor tried to moderate some of the enthusiasms that first arose, but it still brought about enormous changes and led to new experiments in spirituality.

“After Vatican II there were a lot of Houses of Prayer that sprang up all over,” Madeleine tells me, “and I went to one of them in Round Lake, New York, about half an hour north of Albany. It was a small community made up of various and sundry women religious. There was a core group. I think there were five of us who were part of the core group. And the person in charge was trying to make a synthesis of or a hybrid of Integral Yoga and Catholicism. She had studied in New York with I think it was Swami Satchidananda. And so we used that, and we also used the Jesus Prayer. And so I lived there for three years, and then decided it was time for me to leave. So I came back to our community in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, and have lived here since ’76 . And there was an opening for a campus ministry over at the local university – the university of Massachusetts at Dartmouth – and I was hired there, so I stayed there for 37 years.

“Of course, I went back to school – you had to go back to school – and got a master’s in counseling. And then I was part of a couple of counseling centers for a while. It was an inter-faith counseling center. I think I was the only Catholic on the staff. Anyway, there is a small college, Andover Newton, near Boston, and I went there and did a master’s in religious studies, and then I continued and did a D. Min. afterwards. It was a good experience. But it was not a place to learn to nurture your spiritual life. It was a lot of intellectual input.”

I ask why she left the community at Round Lake. She tells me she’d probably got what she needed from it and felt it was time to move on. Then, a little reluctantly, she admits she did have one reservation about the community.

“The person in charge, the woman who started it, she was also a Dominican sister, but she was from Cuba, and she had grown up in a well-off family. My brother and I at one time realized we had grown up poor. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were poor. So I understood the difference between living a life of poverty – basically Zen people would say ‘not attached to your stuff’ – and talking about it. I don’t know exactly how to explain it, but there’s a difference. I knew what it meant because I had lived it, and she knew what it meant intellectually. She really tried to live out of it but then would do things you couldn’t do if you were poor. So I didn’t go too well with that.”

The difference between theoretical and experiential knowledge or understanding is a recurring theme in our conversation.

“But the thing I learned up there was we used to have a morning sit and an evening one when we came back from work. We cleaned houses for a living. And I kept that meditation practice when I left there.”

In addition to sitting with the Jesus Prayer she took advantage of other opportunities as they arose, including a Zen sesshin which the Jesuit, William Johnston, held at Fairfield University. “That was my first long-term sitting.” And when on sabbatical in 1999, she spent two months at Daido Loori’s Zen Mountain Monastery. “It wasn’t any kind of culture shock because the lifestyle they had was what we lived in the novitiate. So that was a no-brainer.”

But essentially she practiced by herself – or with one other sister – for around twenty-five years. Then she did a Zen retreat with another Jesuit – Father Robert Kennedy – on Long Island. “And I spoke to him afterwards and said I was looking for a teacher, and he gave me Father Kevin’s name. And then I became a part of the Day Star Sangha, and now there was a group to sit with.”

I wonder if the formalities of Zen practice were ever problematic for her. She assures me they weren’t. “You know, people get all bent out of shape because somebody’s bowing to the Buddha, and yet their house is filled with their ancestral pictures. So, you know, go figure. Right? I had no desire – still don’t – to convert to Buddhism. It’s not what I’m looking for. Somewhere in your book” – Catholicism and Zen – “I think it was Yamada –who said there are two kinds of Zen. There’s the Zen Buddhist who is a strict Buddhist, and then there’s Zen. And I agree with that. It doesn’t have to be an either/or. I mean Catholicism has picked up all kinds of stuff in its history. This is a technique. And there are some things that are similar to Christianity, and there are some things that are not. Why try and reinvent the wheel if somebody’s already invented it? Outside of the Jesus Prayer, Catholicism does not have a structured tradition that goes from one century to another. They have a lot of traditions that have gone from one century to another like Benedictine spirituality and Carmelite spirituality, but they don’t have that continuity. They have the continuity of wanting to have a relationship with God – that’s there – but there are different ways that gets worked out. So that was one of the attractive things about Zen.”

I tell her about Elaine MacInnes, another Catholic nun, who was the first Canadian – indeed one of the very first Westerners – to be officially authorized to teach Zen. “She told me that she had been drawn to the mystics while doing her novitiate, but there had always been the question of how, nobody could tell her how to develop that kind of prayer life. And when she was sent to Japan and met Yamada Roshi, and what he gave her was the technique. He gave her the how.”

“I would agree with that,” Madeleine says, nodding her head. “I would agree with that.”

“What does the technique do?”

“For me what the technique has done and continues to do is being a way of practicing being in the present right now. I think that’s the most important thing because we don’t live our lives in the present. We live them in the past or we live them in the future. We don’t live in the present, and the present is all we have. If we’re not living in the present, when we come in contact with people and things and situations, we always have our agenda about how it should be, and we miss seeing how it really is. And Zen provides a technique to deal with that. The more I’ve practice, the more simple things have become. Shugen Arnold one time gave a talk at Zen Mountain Monastery on the difference between training and practice. And he said, training is what you do in the zendo. Practice is what you do in the kitchen. And there has to be a transfer of learning, as the educators would say. If there’s no transfer, it’s like learning the multiplication tables and then never using them for anything. And so for me, it’s not just being in the zendo that’s important or sitting every day. That’s not the thing that’s important. If it doesn’t change how I relate to the world and how I relate to people, it’s pretty useless. You need to put into practice what you say is important, otherwise – I think – you’re wasting your time sitting on a pillow because that’s all you’re doing. You’re not living in the present. You’ve got all kinds of opinions about how things should be, and you haven’t let go of those things.”

“You say it impacts the way in which you relate to other people and to the world. Does it impact the way in which you relate to God?”

“It does. I was just looking for something on the computer, and I found an article about Meister Eckhart and his teaching on the fact that we have to let go of God in order to be in relationship. And what he’s talking about is that we have to let go of the God that we’ve created. That’s the piece that’s important because we all create our own God or our version of who we want God to be. You know, this is the only quote I know from Greek philosophy, so don’t be impressed. But Heraclitus said that if an ox had a God, God would look like an ox. And that’s what we’ve done. We’ve turned God into something that we can manage. And so the old cover of Time Magazine that said, ‘Is God dead?’ Well, that’s a real question, because our image – in my experience – has to die. Our image of God has to die, which is not a denial of God. It just simply means that – and this is what Eckhart was saying – God is beyond our ability to know who God is. You know, he says that the Godhead is unknowable. It’s because we don’t have the capacity. Which is different from saying God doesn’t exist. So to go back to how does it have an effect, you can tell by looking at the things that irritate you in life and the judgment that you make on them. For example, before icemakers there was always one cube in the ice try because the last person who used it didn’t fill it up. There was always two sheets of paper on the toilet roll because no one changed the toilet paper. There are always dishes in the sink because someone didn’t do them. And if you look at that in your life, people usually have some very strong thoughts about how they’re always the one that has to pick up after someone else. And that’s a marvelous example of not living in the present. The present is ‘this needs to be done,’ and so you do it. You do it without any judgment about why it’s there and who did it and what I’m going to say to them when I see them.” She smiles. “I can tend to want things to be reasonable and orderly in my life, but life is not reasonable nor is it orderly.”

As we come to the end of our conversation, I mention, that we’d talked about what the community she now leads might expect of her, but what – I ask – is that she hopes for them.

“I hope that they develop their practice to a point where it becomes not just a practice but a way of life. I don’t know how to explain that any further, but it’s not just something that I do, but it is something that I am. It’s part of a person’s being.”

The community remains a group of people who largely self-identify as Catholic but who have also found Zen helpful in the practice of their faith.

“There’s somebody in your book, I looked for it, but I couldn’t find it, but somebody” – Yamada Koun – “says it takes two hands. And I thought that was a wonderful analogy, that you work much better with two hands than you do with one, and the one is not jealous of the other. It gives you stability. I’m aware of that because I broke my arm in December and did a really good job at it. So it was a reminder, one hand is good, but you really need the other one to function. The way I would say it is that there’s one Truth with a capital T. All the other little truths, they’re true, but they’re not the whole thing. I don’t think we can ever understand the whole thing. We might be able to experience it, but I don’t think we can ever really understand it in the traditional meaning of what it means to understand something because I think it’s beyond – well, I know it’s beyond – our ability to express it. And so I think it’s the journey that’s important and not in a Western sense of I read the book, and I take the test, and I pass so I know it. It’s like making bread. Someone asks you how to make bread, so you tell them. And they say, ‘Well, how do you know when the dough’s ready?’ And I tell them, ‘Well, it feels right.’ You can’t get that in the book. And that’s what our practice is like. We can’t get it out of a book.”

Catholicism and Zen: 15-16, 168-80

Your subjects are such interesting thoughtful people Rick. Thanks for sharing. Xxx Ging

>

LikeLike