Adapted from The Third Step East –

The story is told that in 1876, a Japanese fisherman—or possibly an itinerant Kegon monk— named Senzaki came upon the body of a recently deceased woman on the Russian Kamchatka peninsula which extends southward towards the archipelago of Japan. At the woman’s breast, there was a newborn child which the fisherman rescued and brought back to his homeland. The dead woman had clearly been Japanese, but the baby grew up with Chinese features as a result of which Nyogen Senzaki came to assume that his natural father had been from either Siberia or China.

The child was officially adopted by the fisherman and registered as the first-born son of the Senzaki family. His given name was Aizo. His adoptive mother died when he was five after which he was sent to the house of his grandfather, who was the abbot of a Buddhist temple in the Pure Land Tradition. There he was educated in classical Chinese and Buddhist literature.

The grandfather was a devout man who instilled a strong moral sense in his grandson, but he was also a man who lamented the degraded condition to which Buddhism and, in particular, the clergy had fallen. When he sensed that his grandson was drawn to religious life, he encouraged the boy to live by the Buddhist Precepts but discouraged him from becoming ordained. When Aizo was sixteen, the grandfather became ill and his last words to the boy were: “Corruption among Buddhist priests keeps getting worse. Although you have always wished to leave secular life and seek the great Dharma, entering monkhood may, ironically, hinder your goal. Beware of joining that pack of tigers and wolves called monks.”

Aizo returned to his adoptive father’s house, where he began a course of study intended to prepare him for a medical degree. He remained drawn to Buddhist studies, however, and, by the age of eighteen, had read the entire traditional collection of Buddhist scriptures called the Tripitaka. Around this time, he also read the autobiography of Benjamin Franklin and took up Franklin’s habit of maintaining a journal in which he daily recorded his deeds, both good and bad, marking the bad deeds with a black dot. The young Aizo was saddened by the frequency of black dots in his diary. Attracted to the highly disciplined lifestyle of foreign missionaries then proselytizing in Japan, he briefly considered becoming a Christian.

He felt a strong sense of obligation to the members of his grandfather’s temple; their donations had provided the old man with an income and, thus, helped pay for Senzaki’s education. He wondered how he could repay the debt he owed them and, despite his grandfather’s warning, kept coming back to the idea that he might best do so by entering religious life.

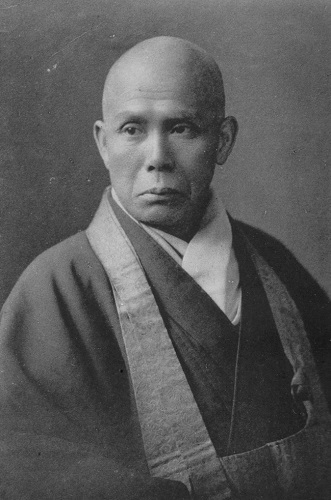

He first learned of Zen through a friend who composed haiku and introduced him to the poetry of Matsuo Basho. This led him to investigate other works on Zen. In his reading, he happened upon the story of Tokusan, a student of the Diamond Sutra. Tokusan realized that his academic study was not furthering his spiritual development so one day burned all the notes he had gathered on the Diamond Sutra and began his formation anew under the direction of Zen Master Ryutan. Inspired by this example, Senzaki gave up his medical studies and sought ordination as a monk. His head was shaved, and he was given the Buddhist name Nyo Gen, “Like a Phantasm.” The name came from a passage in the Diamond Sutra which states that all “composite things” are like phantasms, like figures in a dream.

After his ordination, he began a correspondence with Soyen Shaku who had recently been elevated to the post of abbot of Engakuji Temple, and, in 1896, Senzaki traveled to Kamakura to study with Shaku.

At their first meeting, Shaku was concerned by the physical appearance of the young man who presented himself at the temple. A physician was consulted, and it was discovered that Senzaki had tuberculosis and needed to be kept in isolation. His first year at Engakuji was spent quarantined in a small hut on the temple grounds. From time to time, Shaku would visit Senzaki, whose condition continued to worsen. On one occasion, he asked Shaku, “What will happen if I die?”

“If you die, just die,” Shaku told him.

Once Senzaki’s health improved, he did koan study with Shaku for five years but, at some point, became disturbed by the disparity he saw between the Buddhist vow to “liberate” all creatures and the secluded and comfortable life monks led far from the daily cares of lay life. He was also disillusioned with many of the Buddhist priests he met who, in contrast to the austere lives exhibited by Christian missionaries, paid slack attention to the precepts. He never questioned Shaku’s commitment to the Dharma nor the sincerity of his teacher’s vows, but Senzaki saw little of that same zeal among the majority of priests in the Zen establishment. He recalled his grandfather’s last words and found himself in sympathy with the criticisms common during the Meiji Restoration about the Buddhist clergy. In a commentary on a koan he wrote many years later, Senzaki derided those who proclaimed “themselves Zen masters, just because they passed several hundred koans in the secret rooms of their teachers. They teach their students in their own secret rooms and produce similar Zen teachers. It is a sort of school for magic and tricks. It has nothing to do with the understanding of Buddha Shakyamuni and Bodhidharma. The whole matter is nothing but a joke. No wonder most Zen teachers in Japan now have wives and children. They drink and smoke and accumulate money for the comfort of themselves and their families.”

Senzaki aspired to live the life not of a married priest but of a celibate monk in the manner of the earliest followers of the Buddha. But even as a monk, he did not feel it was his calling to remain sequestered from the world at large. In a letter to Shaku, Senzaki explaind his reasons for wishing to leave Engakuji: “Though it was my original vow to attain Buddha’s Dharma for the benefit of all beings, the present flood of corruption does not permit me to focus on the eternal. I believe I must sacrifice my own practice to work in the here and now.”

Soyen Shaku supported his disciple’s decision to return to his village in order to set up a primary school, which he termed a “Mentorgarten.” His intention was to create an environment in which both students and teachers were mentors to one another. Although he remained a monk, he did not operate the Mentorgarten as a religious institution but rather as a secular school where he hoped students would have an opportunity to develop both their intellectual and spiritual capacities.

It was a struggle to find the funds necessary to operate the school, and Senzaki was disappointed by the lack of support he received from the community he sought to serve. The Buddhist establishment, in spite of interventions on his behalf by Shaku, was equally unsupportive and considered the school heterodox. Senzaki was also disturbed by the increasingly militaristic atmosphere in Japan which was then engaged in the Russo-Japanese war. Unlike Shaku, Senzaki was openly critical of the Zen establishment’s support of the war effort.

Despite their political differences, Shaku invited Senzaki to accompany him as attendant when he accepted an invitation to visit San Francisco, and Senzaki gratefully agreed to do so. Their hosts in California, apparently not understanding the relationship between the Zen master and his attendant, took Senzaki on as a houseboy. His duties included doing laundry and general cleaning. The housekeeper, however, decided the new houseboy’s English was not adequate for his duties and soon dismissed him.

Senzaki gathered his few possessions into a suitcase and set out on foot to find one of the local hotels which catered to Japanese clients. Shaku, who had not intervened on his behalf, accompanied him, carrying the suitcase. When they came to Golden Gate Park, Shaku handed over the suitcase and told Senzaki: “This may be better for you than being hampered by being my attendant. Just face the great city and see what happens—whether it conquers you or you it.” He instructed Senzaki to find work in the city which would help him learn as much as he could about the country and its people. “Do not utter even a syllable, don’t even pronounce the ‘B’ of Buddhism for seventeen years. You must come to understand these Americans before you will be able to teach them. Find work, no matter how modest; work in anonymity for at least seventeen years. Then you will be ready.” After these final words, the two separated, and, although they maintained a correspondence until Shaku’s death in 1919, they never again met in person.

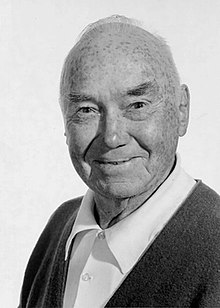

Following his teacher’s instruction, Senzaki worked for a while as a household servant. When conditions in San Francisco forced him to leave the city during the 1920 Anti-Japanese Crusade and Congressional Hearings on Immigration, he worked on a farm near Oakland. After the hysteria in the city abated, Senzaki returned and found employment in a hotel. He held a number of positions there: porter, elevator operator, telephone operator, and bookkeeper. He eventually became the manager and even, for a while, was a part-owner of a hotel. But he was not a natural businessman, and it didn’t flourish. When it failed, Senzaki became a cook. He was also a language tutor, teaching English to Japanese students, and Japanese to American students. In his spare time, he meditated in the Japanese Gardens in Golden Gate Park and spent long hours at the public library, reading American and European philosophy and improving his understanding of the written language. He later confided to Robert Aitken, “I enjoyed reading Immanuel Kant. All he really needed, you know, was a good kick in the pants.” All the while, he continued to write articles on Zen which he sent back to Japanese periodicals, but he did not make any effort yet to teach Americans.

In 1919—the year Soyen Shaku died—Senzaki found a publisher in Japan for 101 Zen Stories. He included two stories about his teacher in the collection. 101 Zen Stories would eventually be translated into English with the help of Paul Reps and then be included in a small volume entitled Zen Flesh, Zen Bones, which also contained their translation of the koan collection known as the Mumonkan or Gateless Gate. Zen Flesh, Zen Bones would become one of the most influential books on Zen in America in the 1950s. The stories in it became some of the best-known Zen tales in the Western world.

Senzaki had not completed his Zen training in Japan, and he never received inka, or formal sanction to teach, but he took Soyen’s words to him in Golden Gate Park as authorization to do so after the specified time had passed. So when the seventeen year period of silence came to an end in 1922, Senzaki rented a hall and gave a public lecture on Zen. The subject was meditation although no meditation instruction was provided. He based it upon an earlier talk given by Soyen Shaku on the subject. From time to time after this initial lecture, Senzaki would present another. He had no permanent temple to work from and called this series of talks a “Floating Zendo.”

His first audiences were primarily Japanese, but eventually a number of Western students also began to attend. As the number of American participants increased, Senzaki started holding separate sessions for them during which he spoke in highly accented English often having to clarify the word he was trying to say by writing it on a blackboard. His command of the written language would always be better than his spoken English. When he felt some of the members of his audience were ready, he began to instruct them in meditation.

In 1931, he moved to Los Angeles where he continued the practice of holding separate lectures for Japanese and non-Japanese audiences. He called the Los Angeles zendo the Mentorgarten Meditation Hall. By now, periods of zazen were a regular part of the evening’s activity.

Senzaki informed his students that the purpose of both Buddhism and zazen was to come to the realization that from “the very beginning we are all buddhas, for our minds as well as our bodies are nothing but Dharmakaya, the Buddha’s true body, with infinite light and eternal life. It is our delusion to see ourselves in the small cells of individual egos.”

This, however, was something each student had to discover on his own; it was not something one could acquire from another. He told them: “I am a senior student to you all, but I have nothing to impart to you. Whatever I have is mine, and never will be yours. You may consider me stingy and unkind, but I do not wish you to produce something that will dissolve and perish. I want each of you to discover your own inner treasure.”

During meditation, Senzaki’s students sat in chairs rather than on cushions. He assigned them koans and held sanzen interviews after the meditation periods. He used the koans of the Mumonkan but also at times assigned a passage from the Christian mystic, Meister Eckhart. Eckhart, Senzaki explained, “said, ‘The eye with which I see God is the very eye with which God sees me.’ We use these words as a koan to cut off all attempts at conceptualizing. When you work on this koan, you will see that there is no God, no ‘me,’ but just one eye, glaring eternally. You are at the gate of Zen at that moment. Don’t be afraid, just keep on meditating, repeating the koan in silence: ‘The eye with which I see God is the very eye with which God sees me.’ There is no reality other than this one eye.”

He insisted that their practice needed to continue beyond the periods set aside for formal meditation. One also practiced by being mindful of the everyday tasks with which one was involved: “—no matter what your everyday task may be, it will turn into Zen if you quit looking at it with a dualistic attitude. Just do one thing at a time, and do it sincerely and faithfully, as if it were your last deed in this world.”

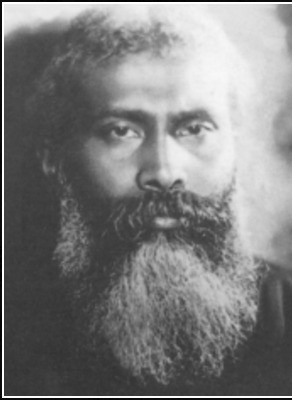

Senzaki recognized that Zen did not have a monopoly on spiritual insight. He respected Eckhart and other Christian mystics, and he told the following story about his visit with the Sufi master, Hazrat Inayat Khan. The meeting took place at the home of a western Sufi instructor, a woman identified as Mrs. Martin. A psychologist, Dr. Hayes, was also present. The meeting began with pleasantries, Dr. Hayes asking the visiting Sufi master his opinion about America.

Then the Sufi asked, “Mr. Senzaki, what, please, is the significance of Zen?”

Senzaki smiled at the master; the master smiled back. Their dialogue, as Senzaki expressed it, was over.

Dr. Hayes, however, thought Senzaki was having difficulty finding the appropriate English words to use, and he explained, “Zen is the Japanese expression for the Sanskrit term dhyana, which means meditation.”

The Sufi raised his hand and shook his head, silencing the psychologist. Mrs. Martin got up, saying, “I have a copy of a book written in English which I believe gives a very good introduction to Zen.” But the Sufi told her it was not necessary.

Senzaki and Hazrat Inayat Khan smiled at one another once more.

Senzaki’s lifestyle was almost ascetic; he tried to live as much like a mendicant monk as was possible in America, although he avoided the outward trappings. He did not shave his head and came to have a distinctive and distinguished head of white hair in later life. He did not wear special garb and was critical of the Japanese Zen priests who came to California and made a show of their robes. He viewed with suspicion and kept separate from both the official Zen hierarchy in Japan and the one being established in North America.

He seldom had any money even when he was working, and, whenever students tried to give him some, he tended to pass it on to others. If students left money in the meditation hall, it was Senzaki’s habit to discover who the donor was and invite them to dinner at a café he enjoyed patronizing.

On one occasion, Senzaki took his dirty clothes to a laundry in his neighborhood but did not have the money to reclaim them. Shubin Tanahashi—the woman who operated the laundry with her husband—saw him walking by their establishment one day and ran out to ask him why he had not picked up his clothing. When Senzaki explained that he could not afford to do so, she made an arrangement with him. Her son, Jimmy, had Down’s Syndrome and was confined to a wheelchair. He was non-verbal and needed extensive personal care. Mrs. Tanahashi offered to do Senzaki’s laundry without charge if he would occasionally assist them with the care of their son.

The boy was thought to be incapable of speech but with gentle patience Senzaki taught him to repeat, in Japanese, “Shujo muhen seigando.” This is the first of the four Bodhisattva vows: “All beings, without number, I vow to liberate.”

The Tanahashis were so grateful for the care Senzaki provided their son that they offered him accommodation in their home, and Mrs. Tanahashi became his first disciple in Los Angeles.

Although Senzaki often struggled with the spoken English language, he was a skillful translator, and a number of artists, poets, and members of the “bohemian” community were drawn to his Zen meetings. Among these was the poet and artist, Paul Reps, who had spent fourteen years in Japan studying Zen and haiku writing. Reps worked with Senzaki to translate 101 Stories into English, after which the two collaborated on a translation of the Mumonkan and the verses accompanying the series of paintings known as the Ten Bulls which illustrate the stages of growth in Zen practice.

In 1934, Mrs. Tanahashi showed Senzaki a magazine from Japan with some poems and prose passages written by a young Japanese Zen monk named Soen Nakagawa. The poet was reported to be living as a hermit on Dai Bosatsu Mountain near Mount Fuji. Like Senzaki, Nakagawa was openly critical of the lax moral lives and careerism of Zen clerics as well the vain ritualism that preoccupied temple life. Recognizing a fellow soul, Senzaki and Reps wrote to Nakagawa, sending him a copy of the translation work in which they were engaged. As a result of this initial correspondence, Senzaki and Nakagawa began an enduring long-distance friendship. In 1940, the younger monk made preparations to visit Senzaki in Los Angeles, but the outbreak of war between the United States and Japan prevented those plans from being carried out.

After the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, public attitude towards Japanese residents in America, particularly those living on the west coast, was highly charged. Anti-Japanese sentiment had been common in California for many years. There had been legislation segregating schools, banning inter-racial marriages, and preventing people of Asian descent from acquiring US citizenship. Senzaki had been so fearful for his own safety in San Francisco during his first years there that he had carried a pistol.

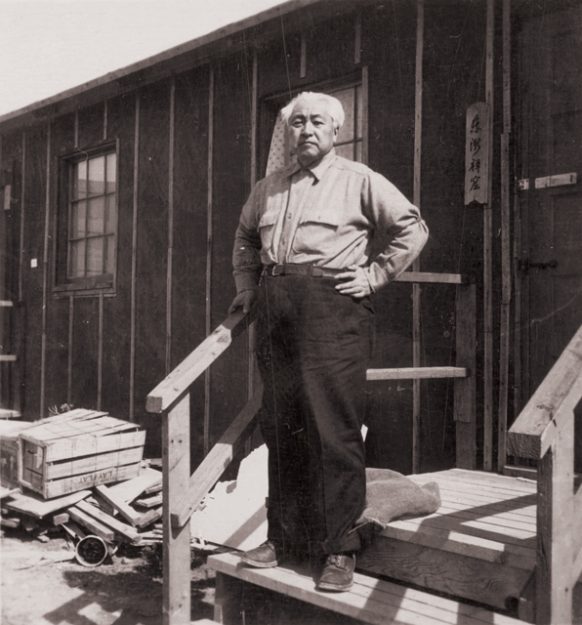

With the outbreak of war, all persons of Japanese descent were excluded from California as well as parts of other west coast states. Families were relocated to internment camps set up inland. Senzaki was sent to Heart Mountain in the Wyoming desert where he shared quarters with a family. He continued to host a meditation group in the small hut in which they lived, sometimes crowding in as many as twenty attendees.

When, after the war, the displaced Japanese returned to what had been their homes in the “exclusion area,” they often found their properties had been confiscated or foreclosed; former neighborhoods where they had dwelt were now occupied by people of other ethnic backgrounds. Many found themselves homeless. In 1945, forty years after he had parted from Soyen Shaku in Golden Gate Park, Senzaki had as little as he had had when he first arrived in North America.

Immediately after release, Senzaki spent two months in Pasadena at the home of one of his disciples, Ruth Strout McCandless, to whom he had given the Buddhist name, Kangetsu. He had entrusted her with his books when he learned he was being sent to Wyoming. Ruth McCandless had taken over from Paul Reps the responsibility of acting as Senzaki’s editor, and she and Senzaki would collaborate on two books published after the war, Buddhism and Zen in 1953 and The Iron Flute in 1961.

After spending two months with the McCandless family, Senzaki returned to Los Angles. He rented a small apartment in Little Tokyo over a hotel which was a popular rendezvous point for prostitutes and their clients. His rooms consisted of a bed-sitting room and a small kitchen. Here he continued meeting with his Japanese and American students seated on wooden folding chairs he had purchased from a funeral home. The formal part of the sessions consisted of an hour’s meditation, a short talk, and the recitation of the four vows. Following this, the members of the group shared a cup of tea, then departed. There was little socializing, and, if members tarried too long, Senzaki would gently encourage them to leave.

Senzaki had remained in America in large part because he thought the American psyche was suited to Zen; he considered it “more inclined to practical activity than philosophical speculation. Because Buddhism is not a revealed religion, its wisdom is not derived from any Supreme Being, nor from any agents of His. The Buddhist believes that we must attain wisdom through our own striving, just as we obtain scientific and philosophical knowledge only by independent effort. To attain prajna [wisdom], we strive in meditation and avoid conceptual speculation.”

He felt that the American mind, “with its scientific cast,” was naturally drawn to Zen. “The alert adaptability of the American mind finds in Zen a quite congenial form of spiritual practice.”

After years of correspondence, Senzaki finally met Soen Nakagawa in 1949 when the younger man visited him in Los Angeles. Nakagawa stayed almost six months. Senzaki had hoped to entice him to remain in America and become his heir, but Nakagawa felt obligated to return to Japan.

In 1955, accompanied by Ruth, Senzaki made his only return visit to Japan after fifty years in America. He visited Soyen Shaku’s grave and Soen Nakagawa, who was then the abbot of Ryutakuji Temple. Because it had been so long since Senzaki had been in Japan, Nakagawa was concerned that he might be uncomfortable with—among other things—the traditional Japanese latrines over which one squatted. So he drew a diagram of a western-style toilet and had the monastery carpenters build one. They were not able to connect the toilet to running water, but it did provide a seat for the visitor.

Nakagawa recognized that his friend was becoming more feeble with the passing years, and he kept apprised of his condition after Senzaki returned to America. In 1958, Nakagawa asked one of his younger monks who spoke English, Tai Shimano, to go to America to act as Senzaki’s attendant, but before Shimano was able to leave, they received word that Senzaki had died on May 7.

At his funeral, Japanese priests chanted the traditional funeral rites. Before the ceremony ended, a recording was played. On it a woman, Seiko-an, read a document which Senzaki had entitled his “Last Words.” Senzaki himself could also be heard laughing in the background and cheerfully correcting Seiko-an’s pronunciation from time to time.

I imagined that I was going away from this world, leaving all you behind and I wrote my last words in English. Friends in the Dharma, be satisfied with your own heads. Do not put on any false heads above your own. Then, minute after minute, watch your step closely. These are my last words to you . . . Each head of yours is the noblest thing in the whole universe. No God, no Buddha, no Sage, no Master can reign over it. Rinzai said, “If you master your own situation, wherever you stand is the land of Truth. How many of our fellow beings can prove the truthfulness of these words by actions?”

Keep your head cool but your feet warm. Do not let sentiments sweep your feet. Well trained Zen students should breathe with their feet, not with their lungs. This means that you should forget your lungs and only be conscious with your feet while breathing. The head is the sacred part of your body. Let it do its own work but do not make any “monkey business” with it.

Remember me as a monk, nothing else. I do not belong to any sect or any cathedral. None of them should send me a promoted priest’s rank or anything of the sort. I like to be free from such trash and die happily.

Nyogen Senzaki’s ashes were divided in two. Half were buried in Los Angeles. The other half was reserved and would eventually be mixed with a portion of Soen Nakagawa’s ashes and buried at the Dai Bosatsu Zendo established by Tai Shimano in the Catskill Mountains of New York.

Nyogen Senzaki compared himself to a mushroom—without a deep root, no branches, no flowers, and probably no seeds. He underestimated the legacy he was to leave behind. He never acquired the celebrity which D. T. Suzuki attained, but through his students—several of whom went to Japan to study with Soen Nakagawa—the practice of Rinzai Zen obtained a foothold in North America.

The Third Step East: 41-56; 9, 59, 61, 67, 69, 102, 111, 113, 114, 115, 116, 122, 127, 138, 148, 149, 150-52, 156, 161, 163, 168, 172

The Story of Zen: 5-6, 229-43, 266, 269, 280-82, 305, 320

4 thoughts on “Nyogen Senzaki”