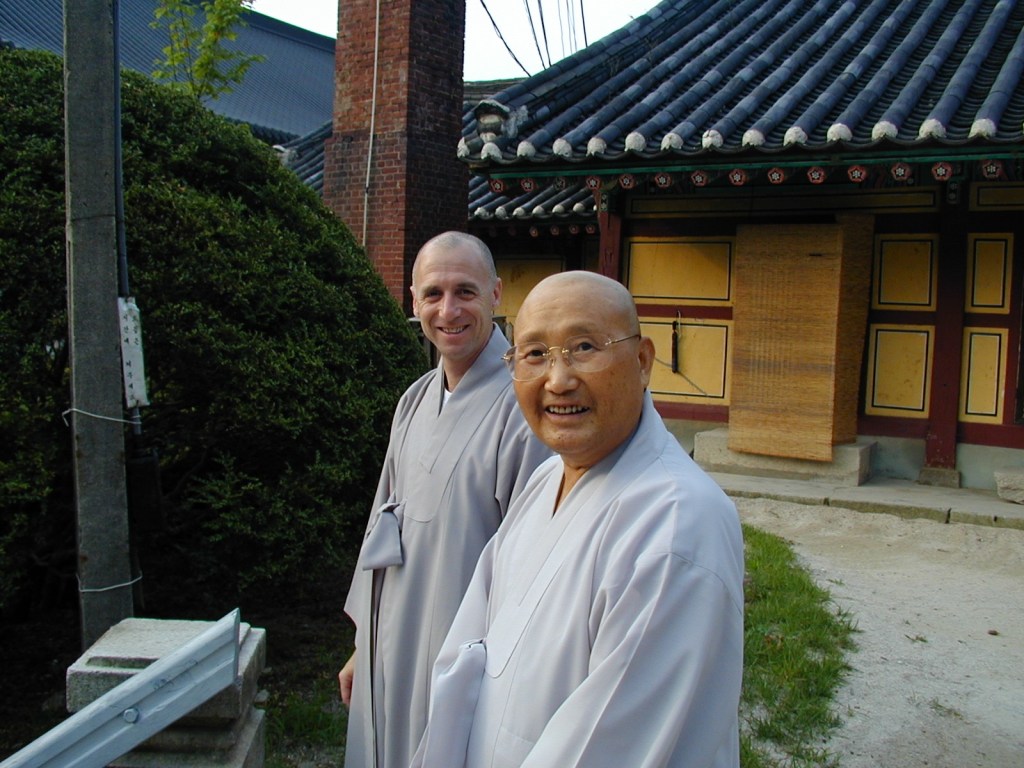

Mu Sang Sa Temple, Korea –

When I was gathering background material on the Korean Zen Master, Seung Sahn – founder of the Kwan Um School – I was advised to interview Dae Bong Sunim, the former abbot and current guiding teacher of Mu Sang Sa Temple in Korea. I only had his Dharma name, so I wasn’t expecting the person who appeared on screen for the videochat to be a 73-year-old white guy from the United States with a strong East Coast accent. “It’s good to have surprises,” he tells me.

Before discussing Seung Sahn, I ask Dae Bong how they first met.

“I was interested in Buddhism when I was quite young, and when I was teenager I became interested in Zen because of a story I’d heard.”

“Maybe we better establish where and when this was,” I suggest.

Dae Bong turns out to be one of those people who need little prompting.

“Okay. I was born in 1950, and in 1976, in America, I was working in a shipyard as a welder. I had thrown away my career – which was just beginning – in psychology a year or so before that. And I really began to be very interested in finding a spiritual group that I could practice with. I was on the east coast of the United States in Connecticut, and I saw the New York Times Sunday magazine section. On the cover there was a picture of an American Japanese Buddhist monk. He was American but – you know – it was a Japanese tradition, and I realized, ‘Oh, there’s Zen in America.’ ’Cause I wanted to find a teacher who could teach in a way that was not dependent on culture. And when I read the article, it was about the opening of Dai Bosatsu, Eido Roshi’s place in the Catskills in New York. And I don’t know; I wasn’t attracted to it. It struck me as a little cold. And so at some point around the end of the year, with one of the guys that I worked with, I drove up to central Massachusetts and just drove around on a Sunday, asking people and looking for signs for a Buddhist Center, and there were some Tibetan groups up there – Buddhist groups based on Tibetan Buddhism – but I was particularly interested in Zen. And then I remembered that I’d heard that there was a Zen Center in Providence, Rhode Island. So on a Sunday in January, I drove up there and managed to find it.”

By then, I was hooked. I steered the conversation back to Seung Sahn but made a note to do a follow-up interview with Dae Bong on his own story.

He was born Larry Sichel in Philadelphia and grew up in in a largely Reform Jewish neighborhood.

“I went to synagogue. Not all the time but a lot. My family had belonged to the synagogue for a few generations. And I was bar mitzvahed and have a big family. One side of the family would gather on the big holidays. Forty people or so at my grandmother’s for the Seder and for breaking the Yom Kippur fast. What I liked the most . . . I think I have a religious mind. I wasn’t into the theology at all, but my favorite holiday, just recently passed” – we are speaking in October – “is Yom Kippur because it’s purely spiritual. You know, many of the Jewish holidays relate to some historical event, and then there’s all of this theological-spiritual meaning that comes out of it. But I just liked this, ‘How have I turned away from God? And turn back.’ That’s it. I’d stay in the synagogue in the evening, all day long, and my family would come and go. Even when I was like 8/9/10, I’d stay there all day. And around 10, I started to understand what was happening. Basically you’re just saying the same two things over and over in different ways. I turned away from whatever . . . Buddhism. Your True Nature. You know? I’ve indulged in ‘I/my/me.’ And . . . now turn back. And that holiday is all between you and God. It’s not like, ‘What did I do bad to other people?’ And then you turn back, and you’re back on track for a year. I didn’t think about things this way then, but it’s called the Day of Atonement. So if you break it down in English, ‘at-one-ment.’ Becoming one again. This is Zen Buddhism! But they add on all this other stuff.

“So, yeah, grew up American Jewish. What happened to me one time . . . And I know this is before 1988 because we were in front of my parents’ house, and I’d been living in the Zen Center about eleven years – I’d been a monk about four years – and two of my father’s old Jewish friends who knew me since I was a baby sort of confront me.” He speaks in an exaggerated accent. “‘Are you still Jewish?’ And I said, ‘Come on, it’s, like, in the DNA, it’s in culture, it’s in character.’ And they’re like, ‘Are you Jewish? You never come to the synagogue. Are you Jewish?’ And finally what I did, I had stretchy pants on. I went like this.” He acts as if he going to pull his pants down to show them that he’s circumcised. “And they got it. The oddest answer to them; it just took away all their thinking. I learned that style from doing koan interviews with Soen Sa Nim. So then, of course, they’re old Jewish guys; they don’t give up. They dropped that question, and they started sayin’ to me, ‘Well, when’re you comin’ back to the synagogue?’ And I said, ‘I like the Zen Center.’ They kept going on, and then I had this thought – I remember – like a boxer. Sometimes a boxer will go down low, get in really close, and hit them in the belly. So I said to them, ‘Actually, I wanna be a rabbi.’ And then their reaction was perfect. One of them said, ‘Don’t do that! Don’t do that! People only tell you their problems. It’s a real headache.’ The other guy says, ‘And they don’t make much money.’ They never questioned me like that again. Whenever I’d run into them, they’d say, ‘You still doin’ that Buddhist thing?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘Ya like it? They give you enough money?’”

He tells me he first became interested in Buddhism when he was eleven and took part in a cultural exchange to Japan.

“I grew up in Philadelphia; went to public school. A very good public school. I was very aware of the American history of slavery and the relationships between African Americans and White people. I couldn’t digest how people could do that kind of thing to others. And now people are still doing it in various ways. Also I was struck that although the street I lived on was nice – 1960, everybody had a car – I knew there was lots of suffering in the houses. It hit me that economics is important – people should have shelter, clothing, food, medical care, and education – but it didn’t take away all suffering. This was on my mind a lot in primary school. I didn’t know anything about Buddha. Then in Japan we visited Kamakura; there’s a big outdoor Buddha. I saw it and immediately felt deeply inside, ‘This person understands suffering and what to do about it.’

“And then I think I told you how my brother told me that story about these two monks.” The story relates how two monks come upon an attractive girl stranded on one side of a stream, unable to cross over without ruining her kimono. So one of the monks picks her up and carries her across. Later that night, at an inn, the other monk complained “Monks are not supposed to touch women, especially young and attractive women.” The first monk responded, “I put her down by the stream. Are you still carrying her?” “I was 16/17 when my brother told me that story, and I thought, ‘Zen has wisdom.’”

In college, he first studied physics. “I wanted to know what is the true nature of the universe, so I wanted to study theoretical physics. I remember in elementary school reading the simple explanations of relativity. I remember sitting in class and thinking, ‘If the universe is infinite, what does that mean?’ And about time, ‘Where’s the line between Tuesday and Wednesday? We know on the clock there’s a line. And on the calendar there’s a line. But in nature, where is the line?’ Actually there’s no line between day and night. That’s something we make up. There’s light and then a little less light, less light, then dark, darker, darker, less dark, less dark, and a little light, more light. There’s no divisions. It’s all continuous. So I got this sense that there’s no division in anything. We make it up. This is true about our body. I talk about this in Dharma talks with people. I’ll say, ‘So, yesterday you ate some rice, and you called it rice. Today it’s part of your skin, it’s the energy of your emotions. It’s your hair. It’s you. And tomorrow you go to the bathroom, and – boom! – something comes out. It’s shit. So rice is you, and you are shit. And then in the old days, the shit goes on the field, and it becomes rice.’ Thich Nhat Hanh talks somewhat like that as well. What are you? I started to realize the whole universe is just one living being.”

I suggest we’d probably skipped ahead a few steps. “So let’s back up. You’re in college. You’re studying physics. How’d you end up becoming a welder?”

“So I switched in my second year from physics to psychology.”

“No wonder you became a welder.

“Yeah. I started university ’68; I finished ’72. I became a welder in ’75.”

“Did you actually practice as a psychologist?”

“I worked as a student on the psychiatric ward of a city hospital as a nurse’s aide to begin with. I had to work in college, and my last two years I got a job working three evenings a week and sometimes nightshift on the weekends, and it was excellent because when you study psychology, you study psychopathology and personality theory, and then I’d think, ‘Yeah. Human beings are like this.’ And then I’d go to work, and my understanding would get blown apart. And then I’d get another idea, some other theory, and I’m like, ‘Oh, they’re like that.’

“After I graduated, I traveled around a little bit, and then I came back to the East Coast, and I got a job in the Whiting Forensic Institute which was a psychiatric hospital on the grounds of the state psychiatric hospital, but it was part of the prison system. I worked there only four months. A friend of mine had a full-time job at the University of Connecticut Hospital on the psychiatric ward as a counselor, and, when he quit, he recommended me, and I switched over there. I did that for two years. Then I realized I’m not psychologically clear enough or strong enough to really do this as a profession, and I don’t think I can get the wisdom I’m looking for going to graduate school. So, that was 1974, and when the hippie movement had somewhat passed, gotten discouraged, but there was still a lot of that sensibility around, and people were getting into ‘back to the land’ and crafts. I decided I wanted to learn pottery.”

“Of course you did,” I sigh, and we both laugh.

“Yeah! Yeah! And my hair was down to here then. So I learned pottery, and I loved it, but I realized, ‘I’m not a potter, and it’s not really addressing the great concerns I have about life’ which I couldn’t quite put in words. Then I needed to work and make money, and I saw a sign that the government would support a four-months program in learning to weld. And my pottery teacher, who was a woman, knew how to weld, and I thought, ‘Well, I’ll learn how to weld, and then I’ll make some money.’ But in terms of life-direction, I was lost. And so I learned how to weld, and all those guys were like from my wrestling team in high school. None of them went to university; many of them were ex-soldiers from Vietnam. Young guys. I knew how to get along with them. The only job I got hired for was at Electric Boat which builds submarines for the Navy. So I worked there for a little more than a year. And socially I learned a lot. My close friends from childhood were all getting Ph. D.s in psychology or finishing law school, and they were going to do poverty law, legal aid, and everybody’s like, ‘What are you doing?’ I just said, ‘I don’t know.’ During that time – I was about 25 – I finally got serious about looking for a Buddhist meditation group. I wanted to practice Zen.

“So one Sunday, I’m talkin’ with one of the guys I worked with. He was a welder also. I don’t know how we connected, but he had been reading Dharma Bums and On the Road by Jack Kerouac. I said to him, ‘I’m going to drive up to Massachusetts and look around for a Buddhist place. You want to come?’” So we drove up there, we drove around all the college campuses, and I asked people if they knew of any Buddhist centers in the area. We spent the day and then we went back home.”

In the days prior to the internet, that’s what you had to do.

“A couple of weeks later, I remembered I had heard there’s a Zen Center in Providence, Rhode Island. I didn’t know anything about the tradition, the master or anything. So on another Sunday in early January, I took my friend and we drove up there. The Zen Master wasn’t there, but his students were having Sunday evening practice, and they always have a Dharma talk Sunday afternoon. One gave a short talk, and another answered questions. We hung around afterwards eating popcorn, and it seemed . . . I liked it. It wasn’t intellectually deep. It was very kind of ordinary. Afterwards, when we were eating popcorn, nobody was talking about Buddhism or anything. Just normal stuff. Then, as I was leaving, somebody said to me, ‘Are you comin’ back?’ And I said, ‘Yes!’ I was surprised that I said it kind of strongly. I meant it. My friend was not all that interested. A month and a half later, I thought, ‘I’m going to go again.’ But there was a branch center closer to where I lived in New Haven, Connecticut. I drove over there on Sunday and after the talk – which was similar, just everyday life – but the point was, ‘Don’t hold your idea’ and ‘What am I? Do you know? What are you?’ Buddha’s ‘Don’t know,’ Bodhidharma’s ‘Don’t know.’ So it was pretty down to Earth. And I asked the guy who gave the talk to teach me how to sit. He said Zen Master Seung Sahn was coming in two weeks to lead a three-day retreat. I decided to sign up for it. I met Zen Master Seung Sahn the night before the retreat when he and a student gave a public dharma talk. He’d been in America about five years, and he could speak English, but it was . . .”

“I notice how all you guys make fun of the way he spoke,” I tell him. “Last time you said it was because it was cute.”

“Well perhaps because he was quite strong, humorous, clear and charismatic, so people were drawn to . . . Sort of like Dylan. People start playin’ and sounding like his voice. In any case, I think I told you somebody asked him, ‘What’s crazy, what’s not crazy?’ He gave an answer that I felt cut across everything. It was just beyond any kind of academic explanation. ‘If you’re very attached, you’re very crazy. If you’re a little attached, you’re a little crazy. If you’re not attached at all, that’s not crazy.’ I thought that is better than my eight years of studying and working in psychology. Then he continued, ‘So everyone in the world is crazy. Because everyone is attached to “I.” But this “I” doesn’t exist; it’s just made by thinking. If you want to not attach to your thinking “I” and realize your true “I,” you must practice Zen.’

“The next day during my first private interview, the Zen Master said, ‘Your before-thinking substance, my before-thinking substance, somebody’s before-thinking substance, the substance of this stick, the sun, moon and stars, all universal substance is the same substance.’ At that moment I thought, ‘I have been waiting my whole life to hear that.’ And I felt he got that 100%. It wasn’t thinking. And I can learn from him how to realize that myself.

“But I didn’t know what to do if you realized your true nature. Later I asked the Zen Master about it. ‘If you attain your true nature and it’s empty, what happens? Do you just disappear? Do you kill yourself?’ Soen Sa Nim would often say, ‘That is only halfway to correct enlightenment. No longer attachment to name and form but if you attach to that, then you’ll make many problems for yourself and others. That’s where you cut your thinking. You just become one with the situation.’ He said, ‘Then you must enter “just do it.” When you’re eating, eat. When you’re talking, talk. When you’re with your family, family mind. When you’re driving, driving mind. Moment-to-moment only help others.’”

I drag the conversation back to his biography. “Somewhere along the line you decided to move into the Zen Center. You said you lived there before becoming a monk.”

“Yeah. I had three retreats with Soen Sa Nim while I was working, and the day after the third one, I quit my job, I went home, and I tried to figure out what to do. I called up the Zen Center in Providence and said, ‘I want to move in.’ They said, ‘Well, come up.’ They knew me because some of them had been at the retreats I did. And they said, ‘Stay for two weeks, and then we’ll see.’ So I moved up there, and I moved in. Then I had to work to support my life there. There was a four-story old building, and there was an American monk there, and he was going to paint the outside of the building during the summer. I remember I moved in on May 6th, 1977. It was also my grandfather’s birthday. But it is really important to me because I was beginning to find my direction. They asked me if I would stay for the summer and help the monk paint the building. I did not have to pay to live there during that time. So I did.

“The Zen center had a pretty strong daily practice. Two hours every night or something like that, and, of course, we got up at – I think 4:30 – 108 bows and sitting forty-five minutes, and chanting for about forty-five minutes. Then breakfast and then most people would go off to work or school. A couple of people stayed in the center. Evening practice was chanting for thirty minutes – or later it became an hour – and then an hour or two of sitting, and extra practice on the weekends and group work periods. So you couldn’t have much social life. But it was okay to me because I’d been through some relationships, and I wanted to understand the practice.”

“So you move in, they put you to work as a painter, you have to get up at 4:30 to do 108 prostrations, and then somewhere along the line you decide that’s not enough, and you want to become a monk.”

“After about a year, becoming a monk kept coming up in my mind. Again it was like I don’t know why I became a welder. I don’t know. I think – for me – this was the way to really attain the truth of the universe, which, of course, was what I was always interested in. What is the truth of our life and how can I help others? I wanted to devote myself to this way. Also I had made a very strong connection with Soen Sa Nim. He had given me good advice about two very difficult things in my life at that time.”

The two things were that he had a son by a woman he had broken up with, and he had recurring thoughts of suicide.

“I signed the paternity papers; I signed an agreement to send a certain amount a month, money every month through the Connecticut Child and Family Services. But that really hit me. I want to be a good person, but I am not raising my own child. When I left this woman, I started having thoughts of suicide. Somehow I struggled my way through the next few years. Then I met a Zen group and a Zen Master.

“When Seung Sahn returned to the Zen center after traveling for two months, I’d been living there and practicing two and a half months. I asked to talk to him, and I told him two things. First I told him, ‘I think about killing myself a lot.’ His response was very interesting. He said,” (Dae Bong speaks softly and once again imitates Seung Sahn’s accent) “‘You did that last life. But that wasn’t your idea. Somebody put that idea in your head. You practice, practice, practice. Then one day you can take that idea out. Then no problem.’ That’s interesting. Then I told him, ‘I have a son who’s about three-and-a-half years old, and I am not raising him. I’ve seen him once since he was born.’ Soen Sa Nim said, ‘Oh, then this karma already cut.’ And he looked at me, and he said, ‘Oh. Not cut.’ Then he said, ‘Any child when they’re nine or ten, they think about, “Who’s my father?” When they’re 15/16 and have some energy, they will look for father. You practice hard. Then when he comes looking for you, you can help him that time.’ So I don’t know if other people talked to him about things like that, but he gave me very helpful advice. I don’t know anything about past lives or not, but I had the motivation to try, not because of finding our true self, but because I did something that was a big, a very big problem. I left a woman with a child. And I left this child.”

“And did your son seek you out as Master Seung Sahn predicted?”

“Yes, kind of at first. When he was around 9, his mother was almost in a car accident. Her father was dead; her mother was an alcoholic. Her sister was far away, and she had broken up with a nine-year relationship, and she suddenly thought, ‘What happens to him if I die?’ And she found me through the Zen Center. I was living in a Korean temple in LA then – 1983 or something – and she called me up. And I thought, ‘Okay, here it is. It’s not him. It’s her, but he’s only 9.’ She told me this, and I said, ‘I’ll raise him if anything happens to you, don’t worry. He can live with me, and I will raise him.’ Then I told Soen Sa Nim about it, and he said, ‘You bring him to see you. Don’t you go visit them.’ But they wouldn’t come, even though I pay for it, so I went to see them. I realized the Zen Master really understood my karma. If I go back into that situation, I’m gonna get fucked up again and that won’t help them or anyone. Anyway I went to visit them, and we met a few times.

“A year later I became a monk and soon after became Abbot of our Zen center in Paris, France. My son’s mother got married, changed her name, and moved. Then I couldn’t find my son and he couldn’t find me. He was 12 at that time. When he was 32, he found me through the internet – he was already married – and we had a great talk for hours, and we’ve been in touch ever since. He has come to see me, and I have him. And we have a good relationship. The first time I visited, I stayed with him and his wife for a week. Before I left, his wife said to me, ‘You guys never lived together? DNA’s incredible. You guys never lived together, but you’re so similar!’” He chuckles. “It’s interesting.”

I ask how he came to be the abbot of the French Center.

“We had just built a monastery behind the Providence Zen Center, past the pond and up a hill. The idea was that the monks and nuns would live there, and we would start to hold our three month retreats there rather than in the middle of the busy Zen Center where people were often coming and going. I went to England in the Spring to visit my brother. There is a French nun who had recently come from Korea to France to start a Zen Center. I went to Paris to visit her for three days. They had just signed a lease for a building; they asked me to stay for a while. I stayed for a week, and everything broke in the new place while I was there. The biggest problem was the toilet on the third floor. The vent pipe for the toilet was underneath the kitchen sink on the first floor. All the shit backed up and came out under the sink. The nun and her friend ran out. I cleaned it all up. Then they called Soen Sa Nim and asked if I could stay in Paris. He said, ‘Tell him to decide.’ They talked to me, and I said, ‘How can I decide? I’m supposed to go back to the monastery. Another monk and I are going to sit a three-month retreat there soon. Nobody else is coming to the retreat.’ So I called Soen Sa Nim. I said, ‘Sir, I’m supposed to go back to the monastery soon where this other monk and I are gonna start . . .’ He said, ‘That monk likes to be alone. One monk’s enough.’ So I said, ‘Okay. I’ll stay for the next two months to prepare for your visit.’ There was a Korean woman who Zen Master Seung Sahn had invited to Paris to be a Guest teacher. She attracted a lot of people. She came and . . . It’s a little complicated. She got along fine. She trusted me. So when Soen Sa Nim was about to leave Europe, and he asked me, ‘What’s your plan?’ I said, ‘I’m going to go back to America. I owe my brother $1000, and I know at the monastery you don’t want me to work. If I stay in the Zen Center, I can work for a couple of months, do house-painting or something to pay him off, then I’m free.’ Then Soen Sa Nim called in a monk who had some money and said, ‘Write a cheque to his brother for $1000.’ My friend gave me the cheque, I said, ‘Thank you.’ Then Soen Sa Nim said to me, ‘So go back to America, go to Korea, stay in Europe. You decide.’ There were no monks in our school in Europe, and I understood what the Zen Master wanted to do there. So I said, ‘Okay, I’ll stay in Paris. How long should I stay?’ Soen Sa Nim said, ‘One year.’ So I stayed, no job, just living and practicing in the Zen center. One month later, the French nun who was abbot ran away. So we called up Soen Sa Nim who said, ‘Okay. You are abbot.’ So I became abbot and stayed three years.”

And in 1993, he took up residency in the Mu Sang Sa Temple Korea, which means he’s been there now for thirty years, although he admits he also “ran off” twice over that time. “I think a mixture of cultural shock, and cultural shock from the Western monks too.”

I tell him that I used to prepare young people to do short-term work assignments in developing countries and that I would explain to them that they probably wouldn’t experience culture shock when they arrived at their placement because they will be expecting things to be challenging. Rather, they would experience culture shock when they returned home.

He nods his head. “That’s true. It wasn’t the Korean culture. It was the Western sunims who shocked me. They had a kind of arrogance. It kind of fit in with the traditional – now changing – Korean Confucian hierarchy. A kind of arrogance towards lay people and towards women. The younger Western sunims at our temple now don’t have that arrogance.”

He did, of course, return to the temple, eventually served as Abbot and continues as the Guiding Teacher.

One thought on “Dae Bong Sunim”