Cuke Archives

There are a handful of digital archives I refer to regularly in the composition of these profiles. One of the most useful is cuke.com maintained by David Chadwick. David is the author of Crooked Cucumber, generally accepted as the official biography of Shunryu Suzuki. Cuke.com originated as a supplement to the book, which was published in 1999. In the 24 years since, the site expanded and a second site – shunryusuzuki.com – added. The combined archives are so extensive that David compares them to the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, California. “It’s a big, giant, sprawling mansion where the woman who owned it thought she’d die if she stopped adding to it. So it’s got stairways to nowhere and it’s got all these rooms. Now it’s like a theme park. Well, Cuke Archives, I’d say, is like a Winchester mansion the size of Los Angeles.” That’s a mite overstated, but the sites do contain a lot of material.

David now lives in Bali. There is an eleven-hour time difference between Bali and Atlantic Canada, where I live. He has just finished dinner when our video chat begins; I’m only on my second cup of coffee of the morning.

“When I was very young, my father was a reader in the Christian Science Church,” he tells me. “And when I was maybe six or something, he quit. And being a reader, that’s like being a minister. He quit because he thought it was too dualistic. He thought it elevated Jesus beyond just being a person who’d awakened. So he got into some New Thought Christian writers like Ernest Holmes, William Walter, and Emmet Fox.”

The New Thought Movement – like Christian Science – holds that illness arises from the mind and can be cured by “right thinking.” It developed at the end of the 19th century and maintained that Christianity – rightly understood – was the culmination of a succession of wisdom traditions which included the ancient Greeks, Daoism, Vedanta, and Buddhism.

“Very influenced by Emerson, Thoreau, there was obviously Buddhist influence on it,” David says. “Anyway, it was a great way to be raised. In our home, God was not an outside power. It was mind. It was mind only. So I’m very grateful for it.”

His father died when David was eleven, but he left a strong influence on his son. “He was my first teacher. He was a really good guy, really nice guy, very gentle.”

After graduating high school in 1963, David spent some time in Mississippi and Chicago involved with the political causes of the day. He lived and worked with the staff of Students for a Democratic Society and met people like Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis. He admits, however, that he “was just a pest. I was a crazy kid, and they were all like policy wonks.”

Then he spent over a year in Mexico. “I was going to school, but I also smoked a lot of pot, and I really got into walking around town and talking to people. I played guitar in a whore house and really got into Spanish. Then in Acapulco I had my first LSD trip, which was really great. And then some friends of mine from Mexico said, ‘Hey, it’s happening in San Francisco.’ So I made my way out there and for about half a year I was sort of grooving on the hippie scene. I had a few more acid trips, and that really tied into the stuff my father had taught me. And I felt like I needed to meditate. So I found the San Francisco Zen Center, and I just plunged right into it. I loved it.” He was 21 at the time.

“Why did you feel you had to meditate?”

“Because one can see, if one is observing oneself, that the mind is way too busy and way too petty normally. So what you want to do is slow it down.”

“This is something you were aware of when you were twenty-one?”

“Oh yeah. So slow it down. And the thing is you can bust through with acid, and I took acid like with the Psychedelic Experience, very seriously, meditating, fasting, no talking.”

The Psychedelic Experience was a manual composed by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert – who later became the Hindu teacher, Baba Ram Dass. It describes what amounted to a sacramental approach to the use of psychedelics loosely based on the Tibetan Buddhist Book of the Dead.

“So I had really profound experiences, but I didn’t do it a lot. I think I had eight trips in all. And that made me think, ‘All right, that’s not going to do it. That’s just like taking a trip there, getting an idea that there’s mind beyond normal mind.’ What I needed was . . . I think I had an image of the wind and time wearing down mountains rather than just blowing them up. And I stumbled on some books on Zen. I wasn’t a big reader, but I found Zen Flesh, Zen Bones and The Zen Teaching of Huang Po translated by John Blofeld, a really great book. I read and re-read Lin Yutang’s translation of the Dao De Jing.”

Shunryu Suzuki was away when David first knocked on the door of the San Francisco Zen Center, so instead he was introduced to Dainin Katagiri, or Katagiri Sensei as he was called. “And I had a discussion with him and said, ‘I think I need a teacher and to meditate with a group,’ which was the perfect thing to say. That’s what they do. That’s the trip, right? And he said, ‘Well, Suzuki Roshi should be your teacher. And he’s in Japan right now, but he’ll be back soon.’ I said, ‘Well, why can’t you be my teacher?’ He said, ‘Well, I could be your teacher, but here he would be your teacher.’”

Katagiri gave him introductory meditation instruction. And eventually Suzuki returned and became David’s teacher, and David decided to commit to the practice for a year. “And I never thought about it again.”

“They won you over?”

“Yeah.”

“How?”

“For one thing, I wasn’t a true believer. I wasn’t that type. And it wasn’t a true believing place. Nobody tried to convert you although some were encouraging. I got to know some people little by little. I liked them. It was cool. But then I hadn’t been there very long when we hear that we’re going be buying land for a monastery. So I was there at this very exciting time. I had some time there in its smaller form, then we were gearing up to buy land in the woods down south to build a monastery. And so I got involved in that. And then we heard there’s this place near the land we’re trying to buy called Tassajara Springs, and it’s really cool. So when we go there, it’s actually contiguous with Tassajara Springs, the same land. And we can walk there in about an hour. So that was great. And then at the last minute I hear, oh, we’re buying Tassajara now as well. And that doubles the money. We were raising $20,000 as a down payment on $150,000 then all of a sudden we’re raising $300,000. That didn’t mean much to me, but Zen Center’s whole annual budget, I’ve heard different figures, $8,000 a year, $12,000 is the highest I heard. So everybody got in the action, but Dick Baker’s genius came out and his energy.”

Richard Baker was Shunryu Suzuki’s most prominent student and would become his only Dharma heir. He managed a capital campaign which engaged people like Alan Watts, Allen Gingberg, and the Grateful Dead. “But what really did it was Dick and Suzuki going to the East Coast and meeting very wealthy donors. Chester Carlson who invented Xerox, a great philanthropist, wonderful man. He supported a lot of good things. Edward Johnson, not really the founder of Fidelity, but what he took over as Fidelity was not at all what Fidelity became. He made it what it became. So we had the CEO of the biggest investment company in the world helping with the fund.”

I ask David why it was a group of California hippies thought building a monastery was a good idea. To David, it seemed a natural thing to do. “And not all of us had been hippies. I’d called myself a semi-hippie. But Suzuki and his students wanted to have a place where they could practice together and live together and be more focused and not have to go home every day. A place to go for a period of time and have a retreat where it’s not just from five in the morning till nine at night. It’s 24 hours. It’s all the time.”

“And why would people want to do that?” I ask.

“Well, for people who get into meditation that’s pretty much a universal tradition. Now our monastery was not a monastery like any other monastery that had ever been. There were women as well as men, married people, unmarried couples. It was really lay oriented. From the first, there were kids. And Suzuki had never seen anything like that. But he listened to his students and together they put something together, and it worked, and it was great.”

“I’m still not getting the why,” I persist. “What did you think you were going to get from all this effort?”

“Good question. One of the fundamental teachings of Zen from a Soto point of view is not to seek an end, not to seek a goal. That what you are doing is learning how to practice, how to cultivate your self, how to be somebody who awakens and to accept yourself as you are, not to try to be someone else, not to try to be something else. So, the practice of meditation, of living together with others, of working together, these are not unique to Buddhism; they are in Christian monasteries too. Monastics, contemplatives of whatever tradition have a tremendous amount in common. Suzuki especially de-emphasized having any sort of practising with a goal. However, there are two sides to everything. You actually can’t do it without having a goal. So, it’s completely paradoxical, and he’d say if it’s not paradoxical, it’s not true, it’s not Buddhism.”

“Let me put this question this way: Why did you think this was a good use of your time?”

“Oh man, I grooved on it. It was great, I loved it. I loved the meditation; I loved the work. I loved and respected the people I was with. And I didn’t worry about it a lot, I just did it. When you do something and it makes you feel better and it makes you feel like you’re getting to some sort of bigger, wider stage in your life, it’s self-evidently good. And you’re also being encouraged by living with others. You know? Everybody’s getting up at 4.30 to go sit at 5:00. It’s great. A lot of it’s like dancing. If we were a dance company and we were getting together and dancing, people wouldn’t ask, ‘What are you trying to get out of this? What’s your goal? What do you hope to accomplish?’ They’d see that the dance itself was rewarding.”

“And that’s the way you felt?”

“I don’t know how I felt. I just did it. And it was good. I loved it. And one of the purposes of having a period of your life when there’s more focus in a retreat-like way is it can give you discipline. It can dig grooves so that you can continue it in your life. You know, Suzuki said, ‘If you want to learn to concentrate, go to a noisy place. If you want peace of mind, do it in an unpeaceful place.’ It’s easy to do it if you’re in beautiful surroundings. So he said that Tassajara, this is all good, but you can’t live here forever. I mean, some people lived there a long, long time. I was there about seven years.”

David speaks with great fondness of his time with Suzuki and what he calls the old temple – Sokoji – which had been established in San Francisco by Japanese Soto authorities in 1934.

“It had an intimacy and a practice that could never be recreated again. And one thing you learn is to appreciate what you’ve got at the time, because it’s not going to last no matter what it is.” He chuckles. “I know that living in Bali too. So, at Sokoji we would have two sittings in the morning with a walking kinhin in between. So two 40-minute sittings. And of course, for the first one you’re getting there early, you get there ten minutes early so you’re sitting 50 minutes, ten-minutes walking, another 40-minute period. Then we would chant the Heart Sutra in Sino-Japanese three times, a little faster each time. And that was the most dynamic chanting I have ever experienced. Nothing we did in the future ever compared to it. After that, we’d all walk out, and Suzuki Roshi would stand at the door and individually bow at each one of us. And that was great. There was a 5:00 p.m. sitting too. That was it. And we’d have a one-day sesshin once a month, and he’d be able to meet each of us and talk. But he just emphasized daily meditation. He did not emphasize enlightenment. He talked about enlightenment, but he said practice is enlightenment – you know – the practice, learning the practice and doing it. It was great.”

“You said he was your teacher. It’s a curious term in some ways. What did Suzuki Roshi teach you?”

“He’d say, ‘Well, I really don’t have anything to teach you.’ But he taught us. He was a good example.”

“Is a ‘good example’ the same as being a ‘teacher’?”

“People talk about transmission, mind to mind transmission. He’d say there’s nothing to transmit. So what did he teach? He taught, ‘Be yourself.’ He said, ‘All I have to teach is zazen and practice.’ He said, ‘I’d rather not give talks. We don’t really need that. We just meditate together, work together, eat together. That’s enough. You don’t need more than that. You don’t need any teaching.’ But the other side of that, of course, is there was teaching. He gave lots of talks. So Zen is called the way beyond words and letters, but you don’t have any ‘beyond words and letters’ unless you’ve got something to give up, unless you know the words and letters and get beyond them. You don’t get beyond words and letters by not knowing the words and letters and just not learning anything. So yeah, he was very short on teaching, and it bothered some people. They’d go find other teachers that would give them koans and meet them daily.”

“You said you spent seven years at Tassajara. Was that continuous? Did you ever take a break?

“I had breaks. Sure. We were pretty loose. I mean, if you were there for a three-month practice period, you were not supposed to leave the whole ninety days. You could if you had to see a doctor. Or if you had a job that took you to town shopping. Or later when I was the director or the head monk, there’d be meetings in the city.”

“You were the boss?”

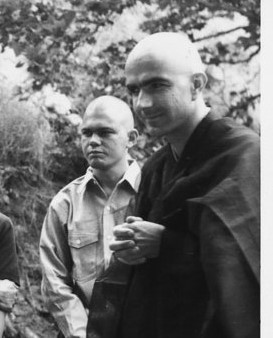

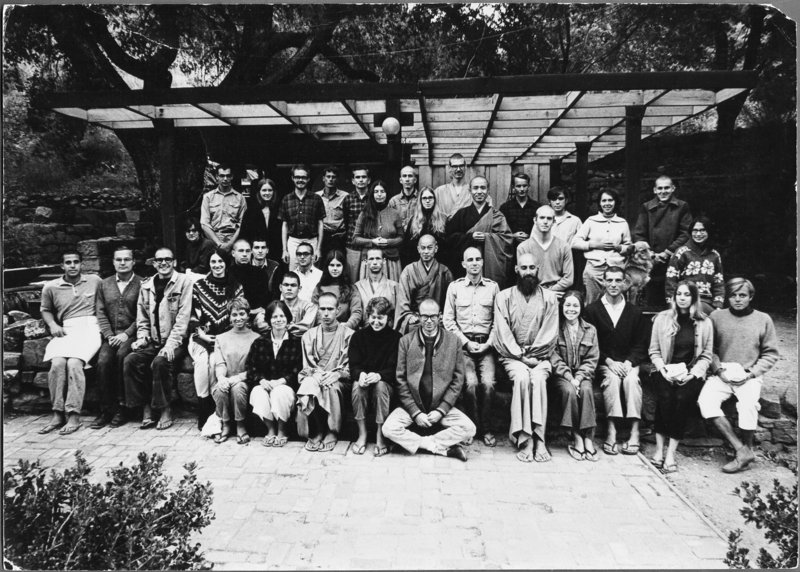

“Yeah. That’s not the boss. When I was director Dick Baker was the boss. There was no other boss!” he says with a laugh. “Dick was the abbot after Suzuki died. When Suzuki died, I was the assistant director of Tassajara. We were all so young. Just amazing. So many of us in our twenties.” He chuckles at the memory, but it’s an important point. What strikes me as I look at the old photos of SFZC or Los Angeles or Rochester is how youthful the faces are. One can almost sense that these people were so young and naïve they didn’t understand how improbable the things they were doing and accomplishing were.

“We did a good job. It was an unusual group. We didn’t have experts telling us what to do. We didn’t pay lawyers exorbitant sums. I’d go visit our Tassajara lawyer and give him bread.”

“And at the end of seven years?”

“Well, it wasn’t quite like that. I was there almost all the time the first five years. And in that time I was gone about half a year studying Japanese intensively in Monterey. But when Suzuki died, then Dick Baker asked me to be the work leader in the city, or the board decided or something. He was only back a couple of months himself from Japan. And so I became the work leader in the city for a year. Year after that, ’73, I was work leader at Green Gulch [Zen Center’s organic farm] and Baker’s jisha [attendant]. He called it MJ, Main Jisha. He had three jishas, one at Green Gulch, one in the city, one at Tassajara. And I was the main one who would go with him off to Tassajara or to City Center or if there’s some event or something. And we got along fine. But I also was work leader there at Green Gulch. I don’t know how I did both, but it wasn’t hard. And then the next year, ’74, I went down to be the head monk. And I was there the whole winter, spring, through the whole guest season, five months. And then in the fall, I became the director. And I was director for a year. And he wanted me to stay. He wanted me to stay and be director because he liked the way I did it. And I said, ‘I can’t stay any longer. I got to get out of here.’”

After leaving Tassajara, David held a variety of posts at SFZC. He became the manager of the Green Gulch Green Grocer shop on the corner opposite City Center at Page and Laguna Streets, where Zen Center had moved when they became too large to stay at Sokoji. He also was the host of the center’s vegetarian restaurant, Greens, for a bit. But things were changing.

In 1983 Richard Baker ceased being abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center. Some people maintain he was fired; David tells me that Baker actually resigned because he was unwilling to accept new conditions imposed by the board as a result of his behaviour and leadership style. Reb Anderson, a Dharma heir of Baker, became the new abbot. David remained close to Baker and, in the spring of 1985, moved to Green Gulch Farm where he was a transitional director for year. In 1987, he was on the SFZC board of directors and was instrumental in creating a new multiple abbot system with term limits because of difficulties with the new abbot.

Then, in 1988, his former wife – Daya Goldschlag – moved with their son to Spokane, and David decided to go to Japan for a few years. Katagiri invited him to join him for a while at Shogoji, a Soto Zen training temple in Kyushu. After his time at the temple, David spent another “half a year checking out other practice centres, meeting teachers, visiting Suzuki’s temple and family, seeing friends and friends of friends, and improving my Japanese.”

I ask him how he came to write Crooked Cucumber.

“I had a friend, Michael Katz, who was a very successful literary agent, and he said, ‘Write a book while you’re in Japan.’ I said, ‘I don’t want output there, I want input.’” But in fact he did write letters about what he was experiencing. “And then I’d make copies and send them to friends and family. Michael said, ‘We can make these into a book.’ So he sent me money to buy a laptop and mailed me software including a typing tutor and told me to get to where I could type in the dark. And so I was going to the temple, having sanzen with the abbot, Shodo Harada, doing zazen and teaching English. And I wrote a lot and had many experiences. Michael got me a deal with Penguin and a small advance; that was nice.” The book was entitled Thank You and Ok!: An American Zen Failure in Japan.

“It focused on Katagiri,” he explains, “half about the time I spent with him and other monks at Shogoji and the other half about living with my new wife and going to Sogenji. And it had some about Suzuki, but I started taking all the Suzuki stuff out of it, thinking this should keep the focus on Katagiri. So I had this Suzuki material, and I started collecting more. Michael and I talked about it and thought, well, we should do a book on Suzuki. It just evolved from the one book to the other. It was just something that happened. And then because I wrote the book, I started a website for it, back when websites were just starting. And so I got a nice little short name, cuke.com. And it was just for some material relating to the book. And then people would write things, and I started putting in interviews or something that had to do with the book, and putting in the Suzuki lectures and just kept doing it, and added shunryusuzuki.com and it just kept growing until the Cuke Archives became like . . . You know the Winchester mansion in San Jose?”

3 thoughts on “David Chadwick”