The Three Pillars of Zen

Larry Johanson now lives in Ontario but grew up in Kingston, Jamaica. He tells me that when he was a child, violence was pervasive on the streets, in the home, and even in the school system. He was deeply unhappy and leery of the form of Christianity common in the country, so while still very young he began what he calls a Vision Quest, seeking an alternative spiritual tradition. “I read a lot of books and came upon the Bhagavad Gita. I was fascinated by the notion of God as something you could discover within yourself through meditation.” However, the Gita didn’t include instructions on how to meditate.

In 1974, when Larry was 16, he came upon Philip Kapleau’s The Three Pillars of Zen. “This was what I had been looking for all my life. This wasn’t an abstract philosophical thing. There’s this guy who went to Japan, who studied and worked with the roshis and came to awakening. And this book is a manual. You want to meditate? You want to see God? You want enlightenment? This is what you do.” He followed the instructions in the book and immediately felt the benefits.

“Because I could meditate, I could study better! I could sit longer. I could read a book and could be so focused that I retained more. And because I could retain more, I did better in school. And because of all of that, my attitudes, my disposition changed a little bit. And I realized, ‘Something fantastic is going on here.’”

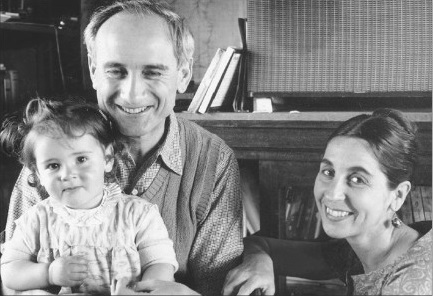

He wrote to Kapleau care of the Rochester Zen Center to tell him how inspired he had been by the book. And he received a reply. Kapleau and his daughter were coming to Jamaica on vacation, and they arranged for Larry to meet them at their hotel in Montego Bay.

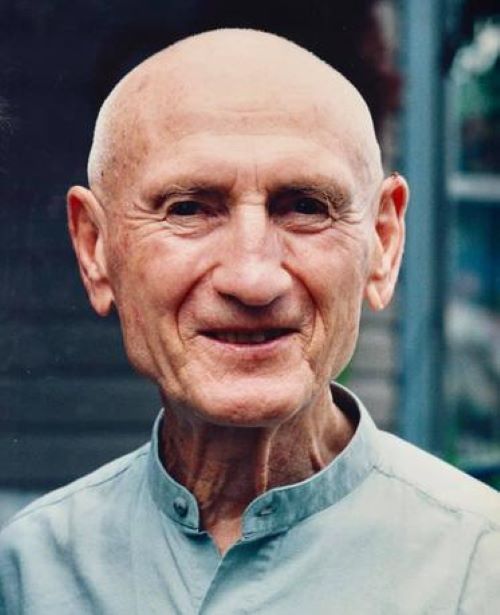

“His presence stunned me. There was a stillness, a quiet, and a silence to him, an authenticity, an assurity to him, and a serenity. And, of course, as a young person whose whole life was in turmoil – my mind, my emotions, everything – it showed up in sharp relief how I felt and what the possibilities were. I was just in awe.”

He committed himself to attain whatever it was he sensed in Kapleau and eventually found his way to Rochester, New York, where he began a lifelong study and practice of Zen.

Stories about the importance of The Three Pillars of Zen in people’s spiritual development is a common motif in the interviews I’ve conducted.

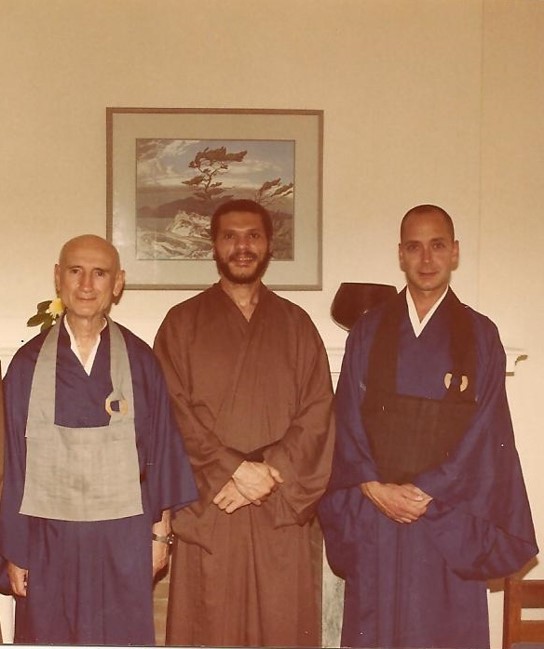

John Pulleyn is currently co-director of the Rochester Zen Center and is a second-generation successor to Kapleau, following Bodhin Kjolhede. Like many others, his interest in Zen came from his reading as a young man. Before Larry’s encounter with Kapleau in Jamaica, a friend gave John a copy of The Three Pillars which he had stolen from the college bookstore (stolen copies of the book is another leitmotif in these interviews). “That was it,” John tells me. “’Cause I’d been looking for how do you meditate. And there was very, very little mention of that. I read all of D. T. Suzuki, and he really wasn’t talking about it. Alan Watts certainly didn’t talk about it.” John was attending Oberlin College in Ohio at the time. “I called the Rochester Zen Center from Oberlin, and I got Roshi Kapleau on the phone. So it was a very small operation when I came. He had three sort of residents living with him. They were in a house on Buckingham Street in Rochester. This was before the move to Arnold Park where the center is now. But, yeah, on the phone Roshi Kapleau said, ‘Well, there are lots of jobs in Rochester. Just come on up.’ So I did that. Took a bus from Toledo to Rochester. Got a room at the YMCA, and then went for my interview with Roshi Kapleau. So I get to the house, and he was just in a sweater. Just seemed to be like a little old man. Very quiet.” He chuckles. “But I couldn’t get a read on him. I wasn’t like immediately, ‘This is it. This is going to be my teacher.’ But I said, ‘This is something I haven’t seen before.’ And a few things from that interview I remember: One is, at some point some issue of money came up – I don’t know why – and he pulled out his wallet, and I thought, ‘Wow! He carries a wallet.’”

“He gave you money?” I ask.

“I don’t remember him doing that, but who knows? And then I was at the Y, and I obviously needed a place to stay. And he said, ‘Well, there are a lot of places you could rent just around here.’ And he took me outside – it was February – and we started walking down the street and just going up to houses, knocking on the door, and when somebody came to the door, he said, ‘This young man has come to study with me, and do you have any rooms to rent?’ And we didn’t find any, but I was just so struck by that, because I was a pretty shy kid, and the idea of just walking up to somebody’s house and asking that was just amazing.”

The importance of The Three Pillars in the transference of Zen to the west can’t be overstated. Prior to its publication, Zen was essentially a concept in North America. After the book’s release, it was clear that Zen was an activity, a practice. Western interest in Zen may well have developed in the 1960s without the book, but it is unlikely it would have been as extensive as it proved to be.

Originally published in Japan, The Three Pillars of Zen consists of translations of a series of introductory lectures given by the Japanese teacher, Hakuun Yasutani, a teisho (formal talk) by Yasutani on the koan Mu,transcriptions of private interviews with students in dokusan – something which had never previously been available in any language – and the personal accounts of eight lay practitioners, Japanese and American, who had achieved kensho. The focus of the book was specifically on zazen. As Kapleau – and Larry Johanson – put it, the book was “nothing less than a manual of self-instruction.”

The Three Pillars is not without controversy. The idea of writing a book about actual Zen practice in order to balance the idealized portraits of Zen more commonly available in the West occurred to Kapleau while he was still training in Japan with Yasutani. He worked on it with the assistance of two other of Yasutani’s students, Koun Yamada and Akira Kubota. Kapleau is given title page credit for editing and “writing” the book, but within the Yasutani lineage it is widely believed that Yamada and Kubota – who succeeded Yasutani as the second and third abbots of the Sanbo Zen school – should have received equal credit.

Kapleau had been the Chief Allied Court Reporter at the Nuremburg Trials. In his book, Zen: Merging of East and West, he wrote: “The testimony at the trials was a litany of Nazi betrayal and aggression, a chronicle of unbelievable cruelty and human degradation. Listening day after day to victims of the Nazis describe the atrocities they themselves had been subjected to or had witnessed, one was shocked into numbness, the mind unable to comprehend the enormity of the crimes. The grim evidence of man’s inhumanity to man, plus the apparent absence of contrition on the part of the mass of Germans, plunged me into the deepest gloom.”

When the trials were drawing to a close, Kapleau prepared to go to Tokyo to cover the war crimes trials there as well. It could hardly, he thought, be worse than it had been in Germany. In fact, he found the atmosphere of the Japanese trials very different. The Japanese, unlike the unrepentant Nazis, seemed to have accepted responsibility for their actions. Kapleau wondered what caused this difference in attitude and was told by acquaintances that it was the result of the Buddhist understanding of karma which held that the current sufferings of the people of Japan were the direct consequence of their behavior during the war.

When he returned to the United States, Kapleau searched out books on Buddhism and Zen, attended meetings of the Vedanta Society, and investigated the Bahá’í faith. He audited the lecture series D. T. Suzuki gave at Columbia University, but none of this alleviated the personal difficulties he experienced after the trauma of the court hearings. Eventually a Japanese friend pointed out that Zen was not something that could be learned through books. So in August of 1953, at the age of 41, he sold his few possessions and returned to Japan.

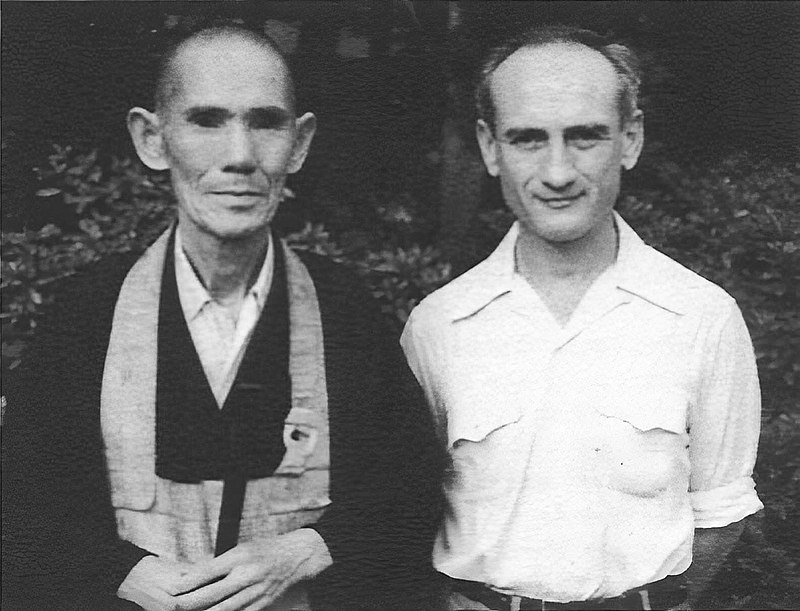

For the next thirteen years, he studied with a series of teachers, Soen Nakagawa, Daiun Harada, and finally with Hakuun Yasutani, who worked with lay people rather than monastics.

In 1965, when he had completed about half of the 800 koans used in the Harada-Yasutani school, Kapleau was ordained a Zen priest by Yasutani and given permission to teach. He did not, however, receive inka, or transmission, defined in the glossary of The Three Pillars as the “formal acknowledgement on the part of the master that his disciple has fully completed his training.” Given the increasing numbers of westerners coming to Japan to study Zen, both Yasutani and Kapleau felt it appropriate that the latter should return to the United States and introduce authentic Zen practice there.

Before he left Japan, Kapleau received a visit from Ralph Chapin, an American who had heard that one of his countrymen was studying Zen and was curious meet him. When he came to Kapleau’s apartment, the galley proofs for The Three Pillars of Zen were spread out on the floor. He read a few paragraphs and asked Kapleau to send him twenty copies once it was in print. When Chapin received them, he passed them out to members of a Vedanta group to which he belonged in Rochester established by Chester and Dorris Carlson. Chester was the inventor of electronic photocopying. The couple were so impressed with the book that they distributed 5000 copies to libraries throughout the country.

Kapleau accepted an invitation from the Carlsons to come to Rochester, which then became his home base in the United States. His first students were members of Dorris’s Vedanta group, consisting largely of women in their forties who were exploring various religious traditions. Kapleau taught them how to sit zazen and set up a regular schedule of sittings. The group, however, did not show up on Sunday mornings because most of them remained regular church attendees.

Then young people who had read The Three Pillars began to make their way to Rochester as well. Almost immediately there was tension between the newcomers and the original Vedanta Group.

One of the three people with Kapleau when John Pulley first visited was Hugh Curran who was my host when I first visited the Morgan Bay Zendo in Maine. Hugh’s family had immigrated from Ireland to Canada when he was young. “Having been raised Catholic,” he tells me, “I had considered entering the seminary after high school. I went on Catholic retreats and, when I came east, went to La Trappe D’Oka, a Trappist monastery in Montreal, to see if I wanted to join their community. I was religiously inclined very early on. I went to college at St Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia and then became a student at Temple University to finish off a degree there. One of my professors was Bernard Philipps, and Bernard had just come back from Japan.”

“How old were you?” I ask.

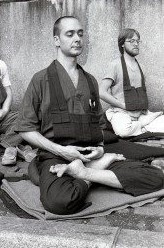

“I was in my early twenties, maybe 21 or 22, and Bernard said, ‘You seem very interested in Zen.’ He was teaching a course and told me I should come to this Zen retreat he’d organized, and the retreat happened to be at a Quaker Center less than ten miles from my house. The retreat was with Yasutani Roshi who was, according to Bernard, a well-known Zen master. I had no idea what I was doing and didn’t even know how to sit cross-legged! I went through a seven-day retreat without any background. Bernard Philipps was also the co-founder of the Zen Studies Society in New York, which had become the place where Yasutani Roshi was in residence for six months each year. Eido Shimano came from Hawaii after Bernard helped get it established. After my first retreat I went to four or five seven-day retreats and monthly one day retreats in the Zen Studies Society. And by the second and third retreats, at one of these Yasutani Roshi verified a kensho experience and encouraged me to develop the experience. He brought me through some initial koans and then said, ‘Now, you really have to keep working on this, keep attending retreats.’ Which I did. Those initial experiences were essentially the turning point in my life.”

When he became subject to the draft during the Vietnam War, Hugh returned to Canada. “I went to Toronto where our family had lived for two years after we immigrated from Ireland, and I got a job as a counselor in the Clifton Home for Boys. I joined a little Zen group that was just forming which included some South Africans, some of them had gone on retreat at the Rochester Center and mentioned Philip Kapleau who was looking for an assistant. So in the spring of ’67, I went to Rochester with a small backpack, and sat with his group. After I spent an evening talking with Kapleau about my Zen retreats with Yasutani Roshi, he asked if I would like to join the Center. I told him that I’d like to try it out, so just like that he accepted me and after returning to Toronto – where I resigned my counselling job – I came right back. I had managed to clear up my draft status by that time receiving a 4C classification as someone who had returned to their own country. I became very involved at the Rochester Zen Center, soon becoming the first monastic, the first cook, the first attendant, et cetera. I also looked after the zendo. I was given a lot of responsibilities based on whatever I was able to handle.”

Hugh was acting as Kapleau’s attendant when the break with the Carlsons took place.

“Dorris had a strong personality and could be very abrupt when she made a decision. She and Chester had been impressed by The Three Pillars of Zen and said they were willing to underwrite the costs of the Center as well as give Kapleau a regular stipend. It was a fairly substantial amount at the time, so he was able to send money back to his wife, deLancey, and their daughter in Kamakura. But the breakup made me feel somewhat guilty because I fed his irritation at Dorris by saying, ‘How come we are letting Dorris tell us what to do so much of the time?’ Dorris would leave little notes with big red ink writing on them after most of the weekly sittings that she attended. She might write, ‘These young people who are sitting with us are smelling up the zendo. Tell them they need to take a bath.’ This was the beginning of a surge of young people coming to the Center. Some of the older people, including Dorris, resented them. And gradually Kapleau became more and more resentful of her. He told me he thought he could work with her Vedanta tradition, but it got more nerve-wracking dealing with her. He became edgier and, unfortunately, I fed the fire by saying, ‘Yasutani or Tai-san [Eido Shimano] wouldn’t put up with this.’ At one point he answered the phone when she called to give him more suggestions about what he should do or shouldn’t do, and he burst out in an angry rant. Next thing you know, she wrote a letter and said, ‘We are no longer giving financial support to the Zen Center.’ Kapleau’s response had not been all that unusual since he tended to bottle up his anger and go into periodic tirades. I desperately wanted people my own age to come to the Center since the older crowd were not people I felt wholly comfortable with.”

And there were more than enough of these young people making their way to Rochester: both single individuals and couples, sometimes with young children, from across the United States, Canada, Mexico, and even Europe. They came expecting the training to be rigorous, and it was. In the early years of the Rochester Center, people talked about “boot-camp Zen.”

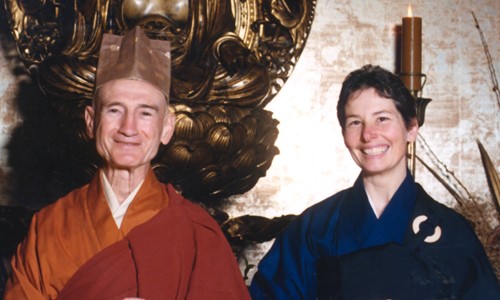

Gail (later Sunyana) Graef was one of those youth. Now a Kapleau heir with her own center in Vermont, she told me there was some irony in the approach he took. “Roshi Kapleau had spent thirteen years in Japan, and the interesting thing about him is that when he was at Harada Roshi’s monastery, it was very strict, very samurai, very – you know – the stick was used and shouts and blows and that whole style of Zen. And he didn’t penetrate his koan when he was there. Finally, he went to Yasutani Roshi’s monastery, which was run be a little old lady. It was very small, very lay oriented, completely different atmosphere, and it was there that he had his break-through. When he came to the US, what style did he bring? Harada Roshi’s style! The stick was used fiercely. It was used – I think – inappropriately.”

An energy-charged atmosphere was induced. When the dokusan bell rang, meditators exploded off their cushions in order to get into line because there was never enough time for all of them to meet with the teacher.

Mitra Bishop, another heir, told me that she was older than many of the members of the Center and, during one retreat, had difficulty making her way through the rush to the dokusan line; besides which she didn’t feel she anything to report. So when the bell rang, she remained on her cushion. After a couple of days of that, a monitor pulled her out of the kinhin line and ordered her to dokusan. “I went in, several feet off the floor, assuming I’d had kensho. Kapleau Roshi said, ‘Why haven’t you been to dokusan?’ And I said, ‘I didn’t have anything to say.’ He pulled himself up and roared at me, ‘Don’t you think I might have had something to say to you!’”

Although it was a time when political activism was common among American youth, Sunyana tells me that Kapleau “actually actively discouraged us from social outreach. And that’s definitely not the case now in Rochester. But at that time, it was. And, of course, this was the ’60s, the ’70s, when there was so much activism going on, and he thought we needed to focus our attention within to develop ourselves. We were so immature and so scattered and so undisciplined and so drug-hazed that I think he was probably right about that. It’s just that there were repercussions to that. And the repercussion was that we thought there was nothing more important in the world than enlightenment. And the more deeply enlightened you were, the better you were. You know? Somehow you were more . . . Buddha-ish or something. That had its effect necessarily. It was not a good one. We were conceited as all get-out.”

In spite of his strictness especially during sesshin, Kapleau also sought to adapt Zen practice to North America. He minimized traditional Japanese ritualism and arranged for English translations of the chants, in particular the Heart Sutra. Yasutani wasn’t happy with the changes and took further offence when Kapleau suggested he should not make use of Eido Shimano as a translator during a scheduled tour of the United States. There were rumors that Shimano’s behavior with female students was at times inappropriate, and Kapleau had serious reservations about him. He and Yasutani became estranged, and Yasutani died not long after, precluding a chance for a reconciliation.

“After break with Yasutani,” Hugh reflects, “Kapleau went into a funk and moped around for a while then called me into his office to ask if I wanted to continue to stay at the Zen Center with him. I said yes because I had no other place to go. In addition I had come to love the Center which had become an integral part of my practice. Kapleau used to say to me that the Zen Center was my Zen practice. After that and for the next couple of years we shared a certain camaraderie together. He could be very likeable as a friend and confidant as well as being a mentor. We would go to movies together, old movies at Eastman House, and in the evenings we’d go jogging together and in the morning we would do yoga together.”

Later Kapleau would express regret over his intransigence with Yasutani, but the immediate question was his status within the traditional Zen establishment. Because he had not completed koan training or received inka, he was not formally recognized by either the Soto or Sanbo Kyodan hierarchies. On the other hand, before Kapleau had returned to the United States, Yasutani had given him permission to teach and had presented him with a robe and bowl symbolic of that authorization. In a Dharma talk, his immediate successor, Bodhin Kjolhede, noted, “Roshi Kapleau has shown me a certificate to teach that was given to him by Yasutani-roshi. He has also shown me the robe and bowl he received, the traditional symbolic objects given a student who is sanctioned by his teacher to teach.” Kapleau decided that this was adequate endorsement to continue teaching. And when Bodhin was offered transmission in the Soto system – as he explained in the same talk – he declined it. “Since I never worked extensively with any Soto teacher, such certification would, I believe, be a mere formality, and contrary to the spirit of Zen’s ‘mind-to-mind transmission.’ Roshi Kapleau’s seal – and now my twenty years of teaching experience – is more than enough for me.”

Kapleau was careful not to claim to be a transmitted Zen master although – after he learned that Richard Baker in San Francisco was using the term – he, too, adopted the title “roshi,” pointing out, however, that the word only meant “venerable teacher.”

By 1981, Kapleau was confident the Rochester Zen Center was firmly established. He himself was tired of the winters in Rochester, so a group of students was sent to Santa Fe to establish a satellite center – what is now the Mountain Cloud Zen Center – where Kapleau intended to retire. Things did not work out as expected.

Mitra Bishop was one of those who went to New Mexico. “Seventeen of us came out from the Rochester Zen Center to build the country retreat center that Kapleau Roshi had always wanted to have, and he was going to go into semi-retirement there and just teach senior students. Then I was with Kapleau Roshi when he moved out here to New Mexico, as his secretary and attendant. He only spent a year. I think there were two factors that entered into his leaving after a year. I picked him up at the airport when he moved here. We’d already bought a house for him and renovated it to work for him, but I took him directly to a picnic that the sangha had planned as a welcome for him. At the picnic, one of the sangha members – one of the local sangha members – stood up and said, ‘Roshi, we love having you here. We want to have you here. But we don’t want you to tell us what to do.’ He quietly took it in. And he lived in Santa Fe for a year, almost next door to the center, to the Mountain Cloud Center, to see how things would work out. He came every Sunday to do sitting, teisho, and dokusan, and invited the sangha to his house for Sunday night movies. It was rare that anyone joined him for the movies and most of the sangha was interested in only minimal involvement, though there were a few of us who were more committed to practice. And at the end of the year, partly because he’d fallen and broken his arm again, partly because he hadn’t realized it was so cold in New Mexico, but partly because the sangha, at least beyond a handful of us, just didn’t seem to be very dedicated to practice, he left.”

There was another factor as well. Kapleau had left his senior disciple, Toni Packer, in charge of the Rochester Zen Center. Once she was on her own, Packer found herself increasingly uncomfortable with some of the forms used at the center, in particular the practice of having students prostrate themselves before her. She instituted a number of changes which some senior members believed subverted the taut atmosphere necessary for Zen practice. Then, shortly before Kapleau was scheduled to return to Rochester, Packer met with him and informed him that she could no longer continue to work within the Buddhist tradition. She left the Zen Center and established her own group, which would eventually settle at Springwater, about an hour south of Rochester. Nearly half of the Center’s members went with her.

When he returned, Kapleau supported some of the changes that Packer had implemented, and the samurai atmosphere of the 1960’s and 70’s began to mellow. He found a winter retirement place in Florida where he spent his last days. He developed Parkinson’s Disease in his 80s. He turned his teaching responsibilities over to senior students and maintained two rooms for himself at the Center.

He died in May 2004 in the garden at the Rochester Zen Center, surrounded by grateful students and disciples. When his body, dressed in formal Zen robes, was laid out, students placed a few parting gifts in the coffin, including some of his favorite chocolate bars and a harmonica. He was buried at the country retreat of the Zen Center at Chapin Mill. The grave is marked by the former mill’s large grindstone.

I never met Philip Kapleau, but I did visit Chapin Mill with Bodhin Kjolhede in 2013. While I waited for Bodhin to finish a meeting he was in, I did the Tai Chi form by Kapleau’s grave, then placed a pebble on the mill stone and was glad to have had the opportunity to do so. I, too, was first introduced to Zen by reading The Three Pillars.

The Third Step East: 199-214; 9, 36, 39, 103, 117, 154-55, 158, 159, 161, 185, 224, 244

The Story of Zen: 6, 21, 92, 225, 244, 254, 292, 296-301, 302, 313, 314-17, 355, 359, 386, 424,

15 thoughts on “Philip Kapleau”